TB's Surprising Results

Did you know? The settlement of cities such as Los Angeles and Denver occurred, in part, due to tuberculosis patients - or consumptives - who moved there seeking better health in the curative climate of the American West. The tuberculosis epidemic also led to the country's very first public health campaign.

By the early 1900s, more scientists began to accept that highly contagious bacteria - and not heredity - spread tuberculosis. The acceptance of tuberculosis as a contagion had a huge impact on American society, not only in medicine and public health policy, but also in recreation, city planning, and even popular fashion.

Waffle Cone

A "penny lick" was a tiny portion of ice cream in a small glass container that vendors sold for only one penny. The glass, which created the illusion of a larger portion, often contained merely just one lick's worth of ice cream. Customers licked the glasses clean and returned them; the vendor would then reuse the container for the next customer. Once word spread about the highly contagious nature of tuberculosis and several other diseases, vendors needed to find a different way of serving their ice cream to customers.

An ice cream vendor in New York City named Italo Marchiony developed a pastry cup to hold ice cream, which he patented in 1903. In 1904, at the St. Louis World’s Fair, another ice cream vendor, Ernest A. Hamwi, independently developed his own ice cream cone made from a crisp waffle-like pastry. With the decline of the unsanitary glass penny lick containers (London banned them in 1899), Marchiony and Hamwi’s edible cones became widely used by vendors across America, with cone production reaching a whopping 245 million by 1924.

Shorter Hemlines

Around the turn of the century, most American women wore long dresses and skirts that reached the ground. But those skirts could be major carriers of germs found on one's floors and out in the streets. Once it became widely known that the tubercle bacilli from someone's saliva could survive for an entire day, women abandoned their long dresses, skirts, bodices, and bustles in favor of shorter hemlines that would not drag along potentially germ-ridden sidewalks.

Shaving

Most men at the turn of the century featured stylish beards or mustaches, but showing off a smooth face became a new trend once public health officials maintained that men could transmit dangerous infectious particles through the scruff of their facial hair. An editorial in a 1903 Harper's Weekly stated, "Now that consumption is no longer consumption, but tuberculosis, and is not hereditary but infectious…the theory of science is that the beard is infected with the germs of tuberculosis.” Ultimately, the clean-shaven look became a symbol of the new middle-class man during the period that Harper's Weekly labeled the "the revolt against the whisker."

No Spitting

Up until the late 19th century, spitting in public was considered acceptable social behavior in America, whether it was merely spitting saliva or discarding one's chewing tobacco. With the increased knowledge into the contagious nature of tuberculosis and other diseases at the turn of the century, flyers and newspapers warned Americans against "the filthy habit" of spitting in public. Dr. Edward Otis, President of the Boston Tuberculosis Association advised, “If you have a cough, and must spit, use a paper napkin or a piece of newspaper, and put it in the stove." Many communities banned spitting in shops, theaters, taverns and required public gathering places to provide spittoons.

Children's Hygiene

In an effort to prevent the spread of tuberculosis through good hygiene practices, public health officials encouraged school-aged children to join the "Modern Health Crusade." School children were given daily "chores" to ensure healthy habits such as washing their hands before every meal, brushing their teeth twice a day, and sleeping 10 or more hours with their bedroom window open. By completing these tasks, children could rise through the ranks within the Crusade - levels like page, squire or knight -- with badges, pins and banners presented to signify their success and status. Organizers claimed these incentives made healthy “chores” less boring, and instead "things to be accomplished with enthusiasm."

Reclining Chairs

Sanatoriums -- establishments for people convalescing from chronic illnesses such as tuberculosis -- often used various forms of reclining chairs or "cure chairs" to help treat patients. Placed outside on porches, the chair backs could be adjusted to tilt at varying degrees, making it possible for patients to get fresh air while resting in comfortable semi-reclined positions. In the early 20th century, wealthier individuals began purchasing stylish versions of these reclining chairs so they could take advantage of the health benefits of sunbathing outside their private homes. By the 1950s, tuberculosis was on the decline in America due to medical advancements like the discovery of effective antibiotics; however, by that time, the cure chairs had come to represent fashionable modernist furniture. Americans still use contemporary versions of the original reclining cure chairs in their living rooms today.

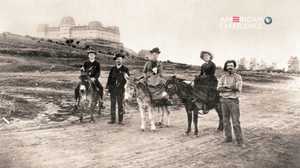

Playgrounds and Recreation Centers

Around the 1920s, public health reformers argued that the health of the nation should not be dependent on sanatoria or hospitals, but should instead rely on recreation in the readily available outdoors. In an effort to encourage more active lifestyles, and thus help to stave off disease, cities launched initiatives to beautify parks with trees and lively vegetation and to build public recreation areas in order to create more pleasant environments. Additionally, the encouragement of larger recreational spaces played a role in creating more space between buildings and thus reducing overcrowding.