Ancient Tunnels

A Ride on America’s First Subway Line

By Cori Brosnahan

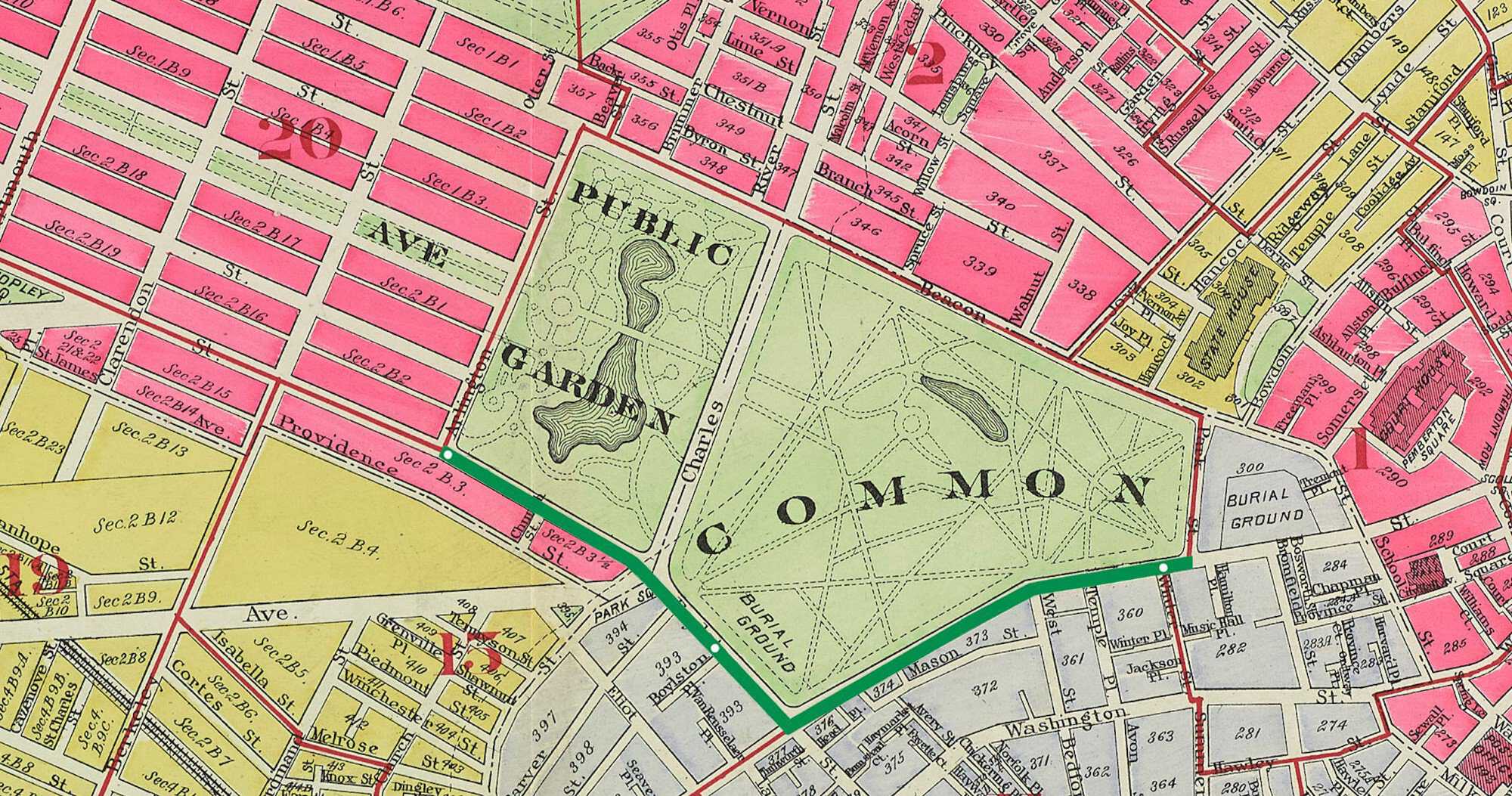

The Race Underground is based in part on a book of the same name by author Doug Most. American Experience rode with Most on the original line — just three stops from one end of the Boston Common to the other — and talked about the past, present and future of the subway.

The Descent: Arlington

People wait at subway stations, but rarely do they linger. Subways, after all, are about movement, about getting somewhere, preferably with as little delay as possible. For city dwellers, they’re a means to an end, not an end in themselves.

But it wasn’t always that way. Everything was new once, and to understand what it was like before we took rapid subterranean travel for granted, we’re lingering at Arlington Street station in Boston, which happens to be the first subway stop in the country — kind of.

“It’s technically not the first subway stop, because this station was aboveground,” says Doug Most. It was, however, the spot where a streetcar descended underground for the first time, stopping, on the morning of September 1st, 1897, at the crest of the hill at Arlington Street. Built for just 45 passengers, it was packed with three times that many.

“People had gotten on aboveground all the way back in Cambridge, so by the time it got here, it was just overstuffed,” says Most. “Their limbs were hanging off the car. As one of the newspapers said, ‘there was not enough room left for a fly to cling.’”

If passengers had expected a speech or a ribbon-cutting, something to mark the momentous occasion, they would have been disappointed. True yankees, the public limited themselves to subtler forms of emotional expression.

“People just treated it like, ‘Oh, it’s just another day,’ even though it was the first subway ride in America. It was just so Boston,” says Most. People who were in the front of the car stood up — they wanted to see what they could see, and people in the back yelled ‘down in front!’ so that they could see. And so the first car disappeared, right here.”

Right here, where we’re standing, decidedly in the way of travelers funneling in and out of the turnstiles — an apparatus, Most notes, invented around the same time as Boston’s subway, befuddling shoppers with large bags and women with wide skirts. Holding up the line being the cardinal sin one can commit on public transit, we join the flow and, like those first passengers 120 years ago, disappear down the stairs, underground.

Hear Doug Most explain why the second-lowest bid won the contract for the Boston subway system.Next Stop: Boylston Street

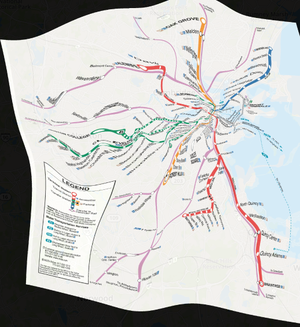

If you’ve spent time on other subway systems, you’d find the trains in Boston surprisingly short. That, Most explains, is because the MBTA (Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority) still uses some of the original tunnels today. Like so many things built in the past, they’re small, and narrow enough that longer trains can’t navigate the tight turns.

Which may also explain why our conversation on the train is interrupted every other minute by the ear-splitting screech of steel-on-steel. Nowhere is that sound more pronounced than coming around the corner at Boylston Street station on the Green Line — a sonic signature that most Bostonians could probably identify with their eyes closed. We look at each other and shrug our shoulders and wait to continue our conversation about the existential confusion Most suffered as a kid born in Boston and raised in Rhode Island by two native New Yorkers.

The auditory assault is only worse when we get out to pay homage to what was actually the first underground subway stop in the country. So we shout standing on the platform, looking at several old photographs along the wall depicting the construction of the original line.

“I love that picture because it shows how basic the tunneling process was,” says Most. “It was horses and carriages pulling dirt out. No giant cranes.”

Through 21st century eyes, the project does indeed look quaint. But that Victorian aura belies the magnitude of the achievement: the political will, the technical expertise, and the sheer manpower involved in a project of that scale and complexity. Then there was the battle for hearts and minds. Public opinion was cautious when it came to electric technology — still new at the time — and overcoming the human aversion to the underground with all its morbid associations was no easy task either.

Considering all that, it can seem incredible that the country’s first subway was ever built at all. But Most says the city didn’t really have a choice.

“It’s hard to describe how crowded Tremont Street was,” he says. “But based on pictures you see from that time, you could walk from rooftop to rooftop of streetcars at rush hour and never set foot on the ground. It was a parking lot — they needed relief.”

Then came the blizzard of 1888, which paralyzed the northeast. In Boston, 50-foot high snowdrifts choked the streets, making transportation impossible and forcing the city to reckon with its untenable traffic problem.

Hear Doug Most talk about the days when the horse was a means of urban transportation — and why that had to end.

The idea of a subway wasn’t new. Across the pond, London had built the world’s first subway in 1863 — though riding it left something to be desired. Essentially a coal-powered steam engine, the London subway cars spewed soot and smoke into the air and lungs of its passengers. A visiting American naval officer named Frank Sprague saw room for improvement. At sea, Sprague filled a notebook with drawings of an electric motor that might whisk travelers through clean, unpolluted tunnels.

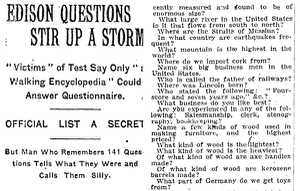

“Frank Sprague was one of my favorite characters in the book because I felt like his contribution to American society was so important and he never got his due, largely because he toiled in the shadow of Edison,” says Most.

Sprague, in fact, worked for Edison’s lab in New Jersey after his stint in the Navy, but left after a year to launch his own motor company. There were other electric motors on the market, but Sprague’s design had a significant advantage: it was able to bear different size loads at the same speed. For this, the inventor earned praise from those in the industry, including his old boss, Edison, who told a reporter that “[Sprague’s] is the only true motor.”

Still, like innovators everywhere, Sprague needed investors. He found one in Henry Whitney, an industrialist and businessman who had previously consolidated a number of Boston’s horse-drawn streetcar lines into the West End Street Railway Company, of which he was now the president.

“Henry Whitney was a big thinker and an entrepreneur who liked the idea of solving problems,” says Most, whose interest in Henry and his brother, the New York politician William Whitney, were a large part of the inspiration for his book. “He was a dreamer. I don’t think he was in it to get rich. He had money. But I do think that he was interested in the idea of changing Boston. And change Boston he did.”

Once Sprague and Whitney got together, the Boston subway became an inevitable fact, but its construction wasn’t without hiccups. One, Most says, was the discovery of a Revolutionary War burial ground under the Boston Common; some 900 tombs were carefully relocated, but the public’s chthonic fears had to be calmed once again. Another rather large hiccup occurred six months before the subway was scheduled to open, when an underground gas leak caused an explosion aboveground on Boylston Street. Two streetcars blew up and ten people died, reigniting fears about subway safety. A massive PR campaign ensued.

Hear Doug Most talk about the discovery of a Revolutionary burial ground during the construction of the subway.

Doubts about the system’s viability would persist until the end. When the tunnel was almost done, the builders brought a contingent of city officials to the Arlington station to show them what the completed tunnel looked like.

“It was sort of intentionally set up in a way that would surprise the officials,” says Most. “The stairs weren’t done yet, so they had to walk down a ramp, and then they came into a dark tunnel. All the officials were gingerly stepping down there, not knowing what they were going to see, and wondering: Would it be damp? Would it be dark? Would the air be breathable? They didn’t know what to expect. Then the builders turned on the lights.”

Most says the officials were pleasantly surprised by how bright and clean the tunnel appeared. But that was only a carefully orchestrated prelude. As the officials nodded to themselves, the builders turned on another bank of lights, illuminating the station like a Christmas tree. Jaws dropped.

“They saw the brightness of it,” Most says, “how clean it was, and how dry it was on the ground. That was the reveal, the big moment, where officials for the first time said, ‘Oh, this really is actually going to work.’”

Last Stop: Park Street

In 2014, Boston’s light rail system (on which we’re traveling) earned the distinction of having the second-most major mechanical system failures of any rail system in the country. And this was before the disastrous winter of 2014–2015, which saw the system operating with fewer cars on reduced schedules for much of the season. It’s been a tough ride; at the close of 2016, the system was still struggling with a roughly $100 million deficit.

In response to the MBTA’s persistent troubles, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker, among others, has called for privatizing various elements of the system to improve overall performance. Proponents of that plan say privatization would increase efficiency — though the essential nature of mass transit seems to work against it.

“People get frustrated with transportation systems, but there is no subway system in the world that makes money,” says Most as we head toward Park Street station, the last stop of the original line.

The only way to turn the MBTA — or any other subway — into a profitable venture would be major fee hikes, which, Most notes, strikes at the institution’s core philosophy. “If you were to charge more,” he says, “then it defeats the purpose of public transportation, which is to make it affordable to everybody. If you charge $10 a ride, suddenly it’s not.”

Despite constant cashflow problems, subway systems in many cities continue to grow. Early this month, the long-awaited Second Avenue subway line opened in New York. In Los Angeles, where there are more registered cars than in all but three states (excluding California), the completion of the “subway to the sea” this past May was greeted as a potential game-changer. Back in Boston, the MBTA hit a record high of 400 million rides in 2014, and seven new stations are planned as part of the Green Line Extension project.

Hear Doug Most explain how radically the subway would change life in Boston.

But on today’s ride we’re more interested in the old stations, and as we get off at Park Street, Most remarks that save the splashy advertising, it looks a lot like it would have looked back in 1897, when passengers completed the first subway ride in America. Watching the cars come and go, as they have for the last century, Most says that more than anything, writing The Race Underground gave him a renewed appreciation for an achievement that’s become such a part of our daily lives, we hardly recognize it as such. To that end, he had some help from his kids.

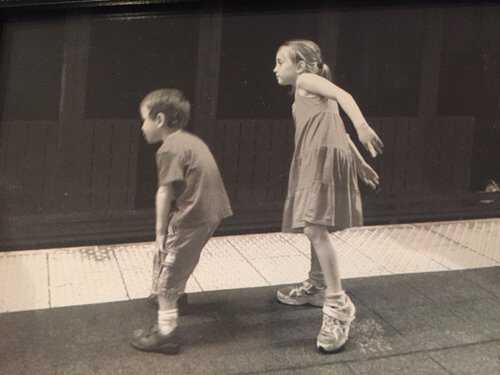

“About halfway through writing the book I was able to get a rare weekend away to go to New York City with my family,” Most explains. “So we took my two kids, who were about six and four. We stayed on the Upper West Side, and we went down to the 79th street station to catch the #1 train downtown. This was one of the first experiences my kids had on the New York city subway, and while we were waiting for the train, they would run up to the yellow line and look down the tunnel for the train, and then run back, and then run up, and then run back — on and on. So I took out my phone and snapped a picture of them, which now hangs on the wall at home. It’s a picture of these two wide-eyed kids staring down the tracks, waiting for the train to come. I love that picture because I like to think that the excitement and anticipation and nervousness that these two kids were feeling had to be similar to the excitement, anticipation and nervousness of New Yorkers or Bostonians on the day of the first subway, waiting for that first train, wondering what it was going to look like — what it was going to feel like to ride it.”