The Role for a Lifetime

By Cori Brosnahan

For the last 25 years, actress and playwright Kaiulani Lee has traveled the world performing her play “A Sense of Wonder,” which tells the story of science writer Rachel Carson. American Experience recently premiered a film about Carson, and took the opportunity to interview Lee about what drives her life’s work.

Dramatizing the life of a writer presents certain inherent challenges. This is especially true if the writer had no well-documented drug problems, no predilection for big-game hunting in Africa, no penchant for fistfights with literary peers or torrid love affairs, but was, rather, a shy, private person who preferred the company of the sea and the conversation of the birds.

And then, if the dramatizer chooses to forgo the few obviously dramatic scenes in the writer’s story — the powerful congressional testimony, the national television appearance — in favor of a small, intimate, one-woman play, most of which takes place in a study, well, she should be prepared for a great deal of skepticism.

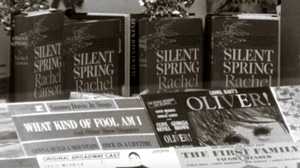

“You can’t do this as a one-person show,” William Shawn, editor of The New Yorker, told the actress Kaiulani Lee. Lee was working on a play (her first) about the science writer Rachel Carson, whose 1962 book Silent Spring challenged the nation’s overuse and misuse of chemical pesticides and illuminated a new way of thinking about the natural world.

Paul Brooks, Carson’s editor at Houghton Mifflin, concurred. “Where,” he asked, “is the drama?”

''The end of the world?’ Lee remembers answering.

Apparently, that was enough. Lee has been performing her play, “A Sense of Wonder,” for the last 25 years. “I never knew it would go on like this,” she says.

Lee’s family is from Maine, where Rachel Carson had a summer home, and the writer’s books were part of her childhood. But it wasn’t until she was an adult that she felt the power of Carson’s words. It was the 1980s. Ronald Reagan was in the White House. The Sagebrush Rebellion was underway and the EPA’s budget was being cut dramatically. Lee was raising children and working as an actress in New York. Her husband, an environmental lawyer, was coming home with disturbing stories about how humanity’s growing technological capabilities were affecting the natural world.

I had an epiphany similar to Carson’s after World War II and the nuclear bomb, when she realized that we had the ability to alter and even destroy the world as we know it. “Nature has always been my cradle, and I realized that I needed to do more than just tend to my family and our little organic vegetable garden,” says Lee.

Lee’s husband encouraged her to re-read certain writers for inspiration, Carson among them. Encountering Carson’s words as an adult, Lee realized that they “articulated [her] heart.” She set out to research everything she could about this private woman who’d made such a public impact.

Famous at the time of her death in 1964, by the 1980s, Rachel Carson seemed to have slipped out of the public consciousness. Her books had long since dropped off the bestseller lists. There was the memoir about Carson by Paul Brooks (which Lee “ate like a kind of ice cream”), but no exhaustive biography. And — at least initially — the keepers of her legacy were less than enthusiastic when she told them what she wanted to do: write a play about Carson. Lee remembered an early exchange with Shirley Briggs, the first director of The Rachel Carson Council, an organization founded after her death by Carson’s friends and colleagues to continue her work on environmental pollution.

“I wanted permission for a play,” Lee says. “But when I approached her, she said ‘You can’t do this. Who are you?’”

Their reluctance was not unfounded. “As soon as Carson died, the attack from the chemical industry was gigantic — it was fierce,” says Lee. “And there were people who wanted to do things about her that either weren’t in her interest or weren’t in her issues’ interest. So they were protective of her.”

But Lee found allies in the people who had known and loved Carson both personally and professionally — among them the editors Paul Brooks and William Shawn — and eventually gained the trust of the gatekeepers.

There was, however, another problem. Lee was an actress, not a playwright. She asked Shawn to recommend a writer.

“He finally contacted me and said, ‘I’ve got your playwright.’ And I said, ‘Oh, can I use your name, Mr. Shawn?’ And he said, ‘You won’t need to dear — it’s you. You have all the passion, all the will, you’ve done all the research, and you know what needs to be said. If you write, I will help you edit.”

Once Shawn threw down the the gauntlet, Lee found herself unable to refuse. She doubled down on her research. She wrote. She researched. She wrote. She researched. She wrote.

“Where’s the play?” said Shawn and Brooks after a few years.

She was, Lee explained, having a hard time with it. By that point, she had decided that she didn’t want to use her own voice at all; she wanted all of the the words to come from Carson herself. Now she was having difficulty weaving Carson’s private voice — the one she used with friends — with her public voice — the one found in speeches, articles, and books.

Eventually, she succeeded in marrying the two. Save a conjunction here and there, every word in “A Sense of Wonder” is Carson’s. The play takes place in the last year of the writer’s life and is structured in two acts. The first is a day in September, as Carson prepares to leave her beloved summer home in Maine. She reminisces about her research as a biologist in Woods Hole and her career with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, about the first time The Atlantic accepted one of her articles and the writing career that followed. She tells the audience that she is fighting breast cancer, and shares her concerns about what will happen to her adopted son, Roger, when she dies. The second act begins two months later in the wake of the furor over Silent Spring. Carson is simultaneously battling the chemical industry, the government, and the press, as she struggles to get her message out to Congress and the American public.

To capture the details of how Carson dressed and moved, Lee turned to those who knew her. Shirley Briggs of The Rachel Carson Council, having warmed to Lee’s endeavor, showed her how Carson might have done her hair and what color clothes to wear (“She always wore bright-colored tops — she was very cheerful!” Briggs insisted). Everyone who was with Carson during the last year of her life told Lee that when Carson was in private, she moved with great difficulty and pain, but that when she was in public, she tried to cover up any signs of illness.

Before Lee took on Rachel Carson, she had starred in plays on and off Broadway, and appeared in TV shows like Law & Order and films like The World According to Garp. But playing the science writer was unlike any role she’d ever undertaken.

“It was terrifying because I so adored her,” Lee says. “And I knew how important it was that other people fall in love with what she had to say. I knew I was the messenger and I couldn’t fail. I had to earn every second on stage.”

Lee first performed “A Sense of Wonder” at an event for the NGO Beyond Pesticides in Washington D.C. in 1991, receiving the first of many standing ovations. As she left the stage, people were shouting questions. In those early days, Lee estimates that sometimes up to 70 percent of her audiences had no idea who Carson was. This has changed.

“Now everybody knows her — everywhere I go,” Lee says. “She’s had such a renaissance, it’s just fabulous.”

Bill Moyers Journal: Remembering Rachel Carson with Kaiulani Lee from BillMoyers.com on Vimeo.

Every few shows begot another. Over the last quarter-century, Lee has performed at dozens of high schools and over one hundred universities, at fish and wildlife refuges and for breast cancer survivors. She’s brought Carson’s words to the Smithsonian Institute, to the Albert Schweitzer Conference at the United Nations, to the Department of the Interior’s 150th anniversary, and, in 2007, to Capitol Hill. And that’s just in the U.S. “A Sense of Wonder” has played in every province of Canada, as well as England, Italy, India, Japan, and, most recently, Bangladesh. The play was also turned into a film, which aired on PBS in 2010. Lee has found her audiences to be exquisitely receptive.

“Tears almost always come out at some point in the play — I never know when because the play’s so full of emotion. Laughter always comes. If the audience gets her humor and understands the seriousness of the situation, then they’re so hungry for the humor that they laugh like it’s a comedy. And that lets me take more time with the next beat. It’s musical what goes on between [Carson] and the audience. And it’s always different — which is why I never tire of it. It’s like a different play every night.”

For one especially memorable performance, the audience included the person who was was closest to Carson — her grandnephew and adopted son, Roger. Lee had written to him early on in her research to tell him about the project — and explain why she didn’t want to interview him for it.

“I said, ‘I don’t want to get your memory of her mixed with all the notes I have from her about her relationship to you. I want to keep it her point of view — I hope that doesn’t offend you,’” Lee remembers.

She was “just frozen” backstage the night Roger came to see the play. But after the curtain fell, Roger’s wife came up and introduced herself.

“I said, ‘Was it alright?’ Lee recounts. ‘And she said, ‘Oh, yeah.’ And I said, ‘Where’s Roger?’ And she said, ‘He’s the guy in the back row with his head in his hands.’ I went over to him, introduced myself, and we’ve been fast friends ever since.”

But even that formidable seal of approval hasn’t allowed Lee to relax.

“Every year my desire, my need to portray her accurately grows,” Lee says. “I try not to make her too old, not to make her too sick, not to make her too passionate, not to make her too funny, not to make her too dour, but to be her. Every single night I perform this play is scarier than the night before.”

For Lee, the stakes are just too high. There are two messages she hopes to get across each night. The first is Carson’s — “Her underlying message with everything she said and every piece of writing is the interconnectedness of all life,” Lee says. “We need to understand that even though the lines are invisible sometimes to our eyes or ears, they are there, and that we will all sink or swim together.”

The second message is Lee’s own. She wants the audience to walk away inspired by the “deep love and courage Rachel Carson had.”

“I think that today when people are so frightened of sticking their heads out, so frightened of taking a stand because they don’t know what’s going to happen to them — it’s important to show that we each have the ability to make a difference.”

“A Sense of Wonder” is Lee’s own way of making a difference. It is, she believes, the most important thing she’s done in her life besides raise her children. For this actress, it’s not the role of a lifetime so much as it has become the role for a lifetime.

“I’m going to do it until I can’t remember my lines,” Lee says. She laughs. “And then I’ll probably walk around with my script.”

To learn more about Kaiulani Lee and “A Sense of Wonder,” visit www.kaiulanilee.com.