Fifty years of Jeans Fashion

From leisure suits to low-rise cuts, a brief history of the all-American fabric

For a long time, “fashion” had nothing to do with it. Even before the Industrial Revolution, laborers from around the globe–farmhands, builders, miners–often wore some kind of homespun denim workwear. But by the latter part of the 19th century, blue jeans were poised to become a core product of American mass manufacturing as they rolled out of the same factories operated by the working-class people who wore them.

It wasn’t until the first half of the 20th century that blue jeans brands–among them Lee, founded by a hardware store owner in Kansas; Blue Bell, the North Carolina overall company that would remake itself as Wrangler; and, of course, San Francisco’s Levi Strauss & Co., which began producing blue jeans in the 1870s–began to understand that their work pants appealed to many customers for their adaptability beyond the workplace. Well-to-do vacationers discovered denim trousers during their therapeutic visits to the “dude ranches” of the not-so-Wild West. Parents, inspired by the Western movies that dominated at the box office during Hollywood’s early decades, began to dress their young boys in cowboy outfits. And women took to wearing the oversized jeans that belonged to their boyfriends, creating a casual style that still exists today.

But it was the rise of a new American demographic–the “teenager”–that would button up the classic blue jean’s place in popular culture. With the growing middle-class prosperity that followed World War II, more school-aged adolescents and young adults were free to earn their own money, drive their own cars and find their own pastimes. They were the audience for the hybrid new music called rock ‘n’ roll, and for the angst-driven films about young rebellion that began to appear on movie screens across the country. Those kids helped refashion the uniform of the country’s working class into a blank canvas for self-expression that every subsequent generation has adopted as its own.

1950s

By the midway point of the 20th century, California would surpass New York as the country’s most populous state. The suburbanization of America fueled a collective nostalgia for the Old West; from the 1930s through the ‘50s, Westerns were the most popular genre of film in Hollywood, and early television audiences were inundated with cowboys and little buckaroos.

Glamorized in films such as “The Wild One” (1953) and “Giant” (1956), the Method actors Marlon Brando and James Dean helped make jeans the uniform of the new generation’s slouching insouciance. For his breakthrough on Broadway in “A Streetcar Named Desire,” Brando wore no underwear during the fitting for his jeans and had the inside pockets removed.

1960s

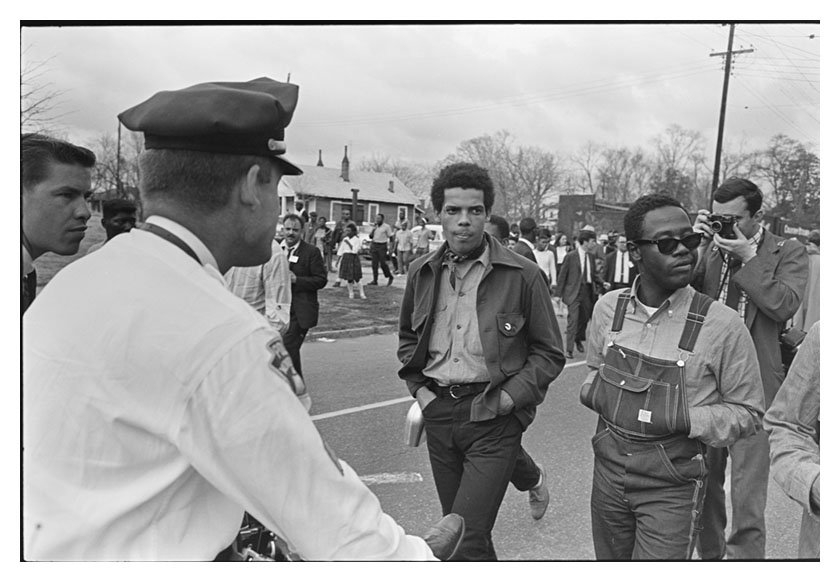

During the Civil Rights demonstrations of the 1960s, civil rights workers often wore jeans, overalls and denim barn jackets to express their solidarity with the working poor African Americans they sought to organize. The practice of sharecropping, a vestigial reminder of slavery, was still the reality for many Blacks in the South.

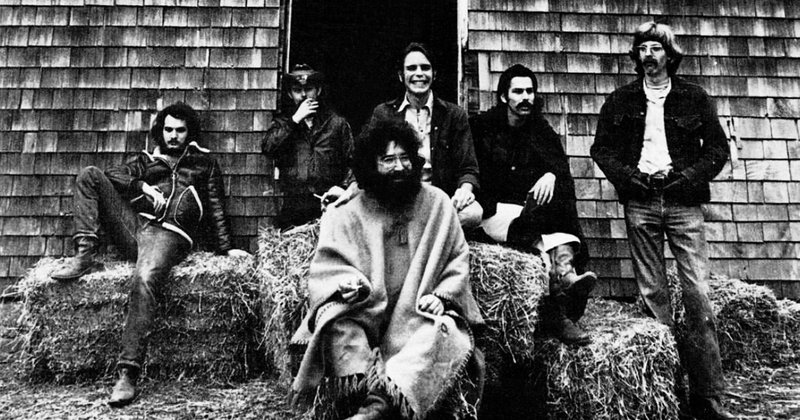

By the late 1960s many in the counterculture were growing disillusioned with city life and its various ills–pollution, racism, violence. The “Back to the Land” movement was well represented in the world of rock music, which rediscovered rural traditions and acoustic guitars.

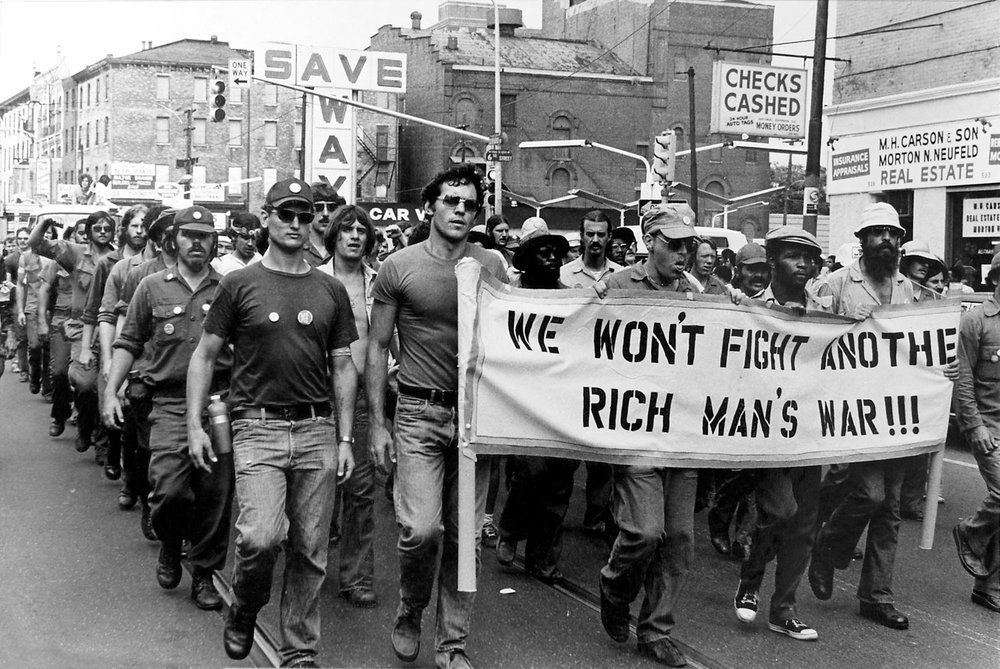

The young people who fought the Vietnam War and those who protested against it were members of the same generation, and they’d all grown up wearing blue jeans. By the 1970s, when many returning soldiers began to grow their hair long, it was sometimes hard to tell the two sides apart.

1970s

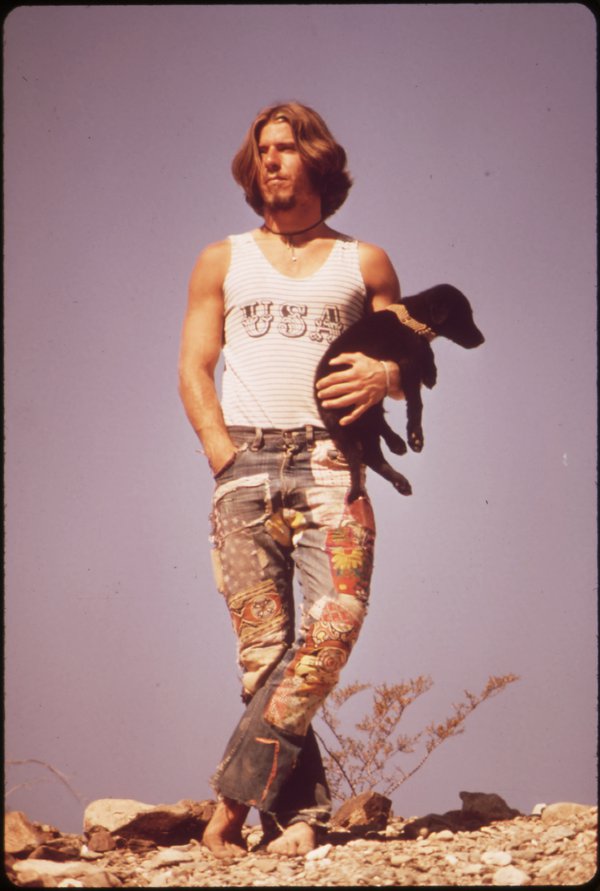

By the beginning of the new decade, hippies were wearing jeans so old that they often required elaborate patchwork. Wearing tattered jeans became a rite of passage that would be handed down through subsequent generations, with the “distressed” look often reproduced for retail.

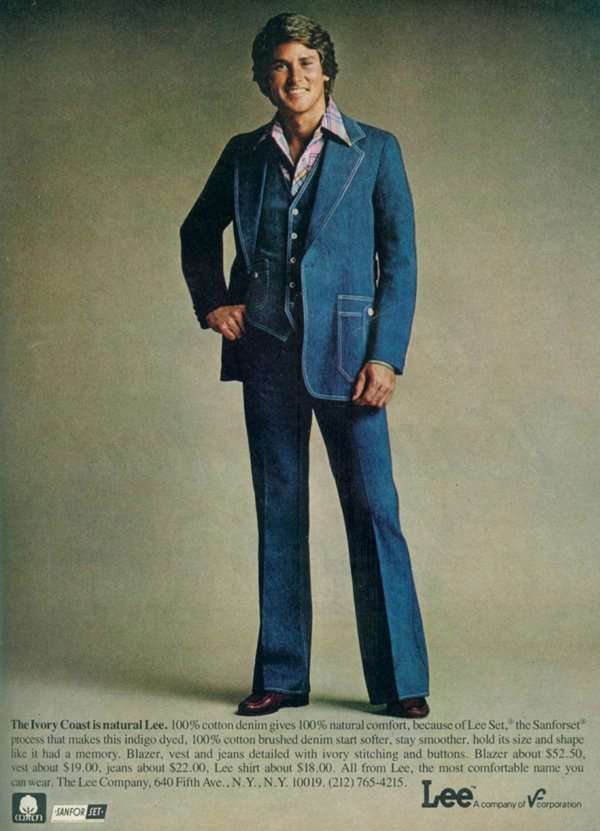

As the 1970s unfolded, most of the major jeans manufacturers–Levi, Lee, Wrangler–diversified wildly, producing plaid shirts, corduroys, polyester slacks and more. It was Lee that first introduced the “leisure suit” to the market. Years later the company would poke fun at its own role in the trend, claiming it had been “simply ministering to the whims of a fickle public.”

Jeans were becoming increasingly stylized, with boutique brands designing bell-bottoms and “hip huggers,” as the disco craze ignited in the mid-1970s. A generation once defined by its long hair and scruffy clothing was moving uptown and hitting the nightclubs. When the ready-to-wear giant Murjani Group sought a figurehead who would represent “American royalty” for a new line of designer jeans, their second choice, the heiress Gloria Vanderbilt, accepted. (Their first, Jackie Onassis, declined.)

1980s

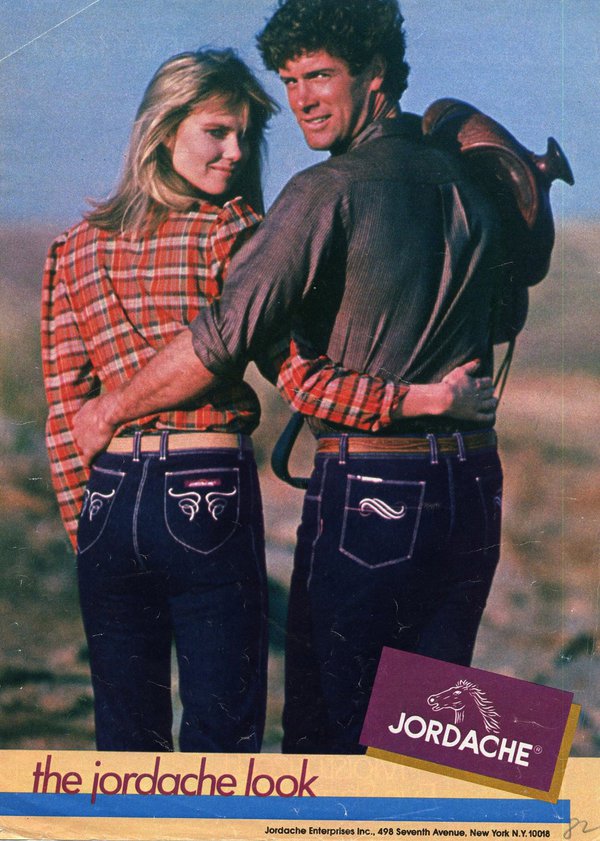

By the 1980s, America was awash in designer jeans. If your posterior wasn’t branded with a top brand name (Sasson, Sergio Valente, Calvin Klein) or a recognizable pocket design, you were persona non grata to the fashion world. If you were wearing Jordache, as the jingle proposed, “You’ve got the look I want to know better.”

“Don’t want nobody’s name on my behind,” declared the Reverend Run from Run-D.M.C., the first rap act to enter regular rotation on MTV. The group was partial to their Adidas sneakers, but when it came to pants they preferred a sturdy old pair of Lee jeans over name-brand designer wear.

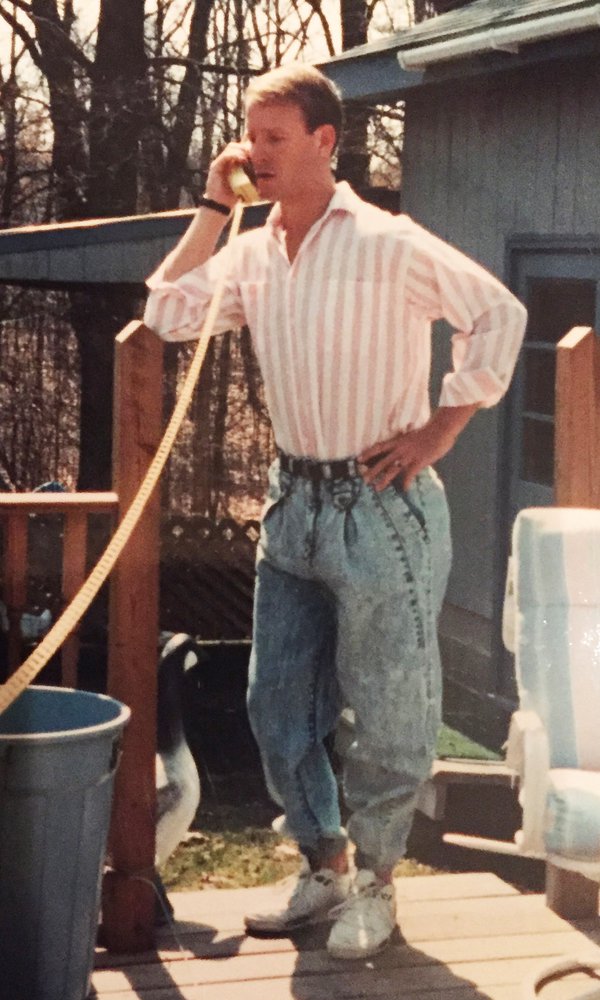

With the retail industry perpetually seeking new ways to market the same old blue jean, the decade saw the brief rise of stonewashing and acid wash, techniques for softening denim using pumice stones in heatless dryers. Like every other denim innovation, stonewashing has enjoyed occasional resurgences.

1990s

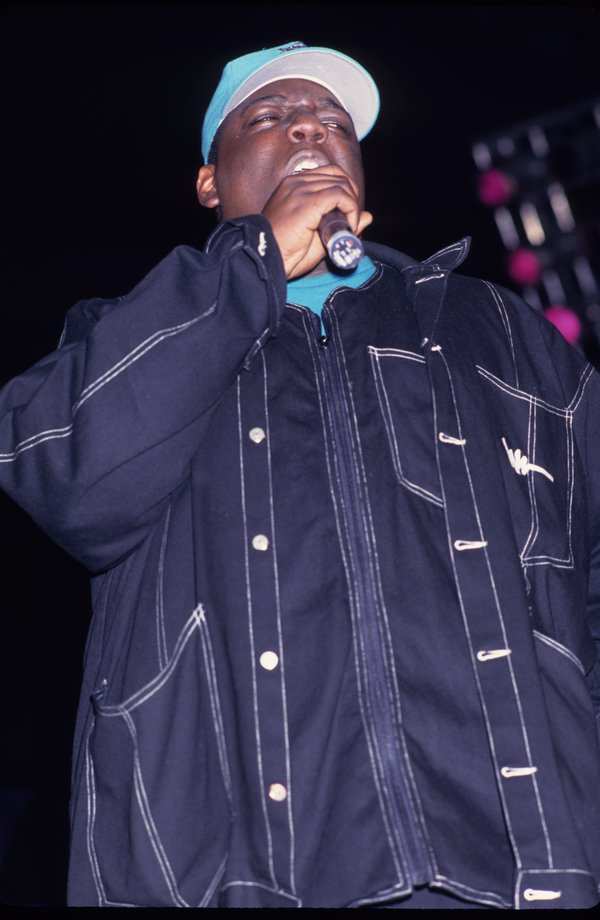

Asking himself “Can I become the Ralph Lauren of the streets?,” the young entrepreneur Carl Williams began selling his designs out of the trunk of his car in Brooklyn in the late 1980s. Calling his company Karl Kani, his oversized jeans, eagerly embraced by the hip-hop community, would dominate the culture in the 1990s.

By the turn of the millennium, jeans trends were moving from an excess of material to “less is more.” Led by L.A. boutique brands Earl Jeans (launched by Hollywood stylist Suzanne Costas) and Frankie B. (the brainchild of Daniella Clarke, wife of a former member of Guns N’ Roses), the slim-fitting “low-rise” era had begun. The hipster’s skinny jeans were just around the corner.

James Sullivan is the author of five books, including “Jeans: A Cultural History of an American Icon.” He is a longtime contributor to the Boston Globe and program director for the Newburyport Documentary Film Festival.