Rosie the Riveter Isn’t Who You Think She Is

The real story behind a WWII icon

In early 1942, the Bureau of Labor Statistics predicted a big problem: Unless action was taken, a shortage of six million workers would bring the country’s productivity to a halt by the end of 1943. Just months after the United States formally entered World War II, American men were leaving for active duty overseas, and it was critical to prevent interruptions to industry. The solution was as clear as the problem. “With the exception of the few hundred thousand boys of predraft age,” a government study stated, “this gap will have to be plugged almost entirely by women.”

President Roosevelt tasked the Office of War Information, a newly formed federal propaganda agency, with selling the idea of women workers to the country. “These jobs will have to be glorified as a patriotic war service if American women are to be persuaded to take them and stick to them,” said an OWI report. “Their importance to a nation engaged in total war must be convincingly presented. Joining the government’s effort were private industry and the American media, who together generated some of the era’s most enduring and well-known images.

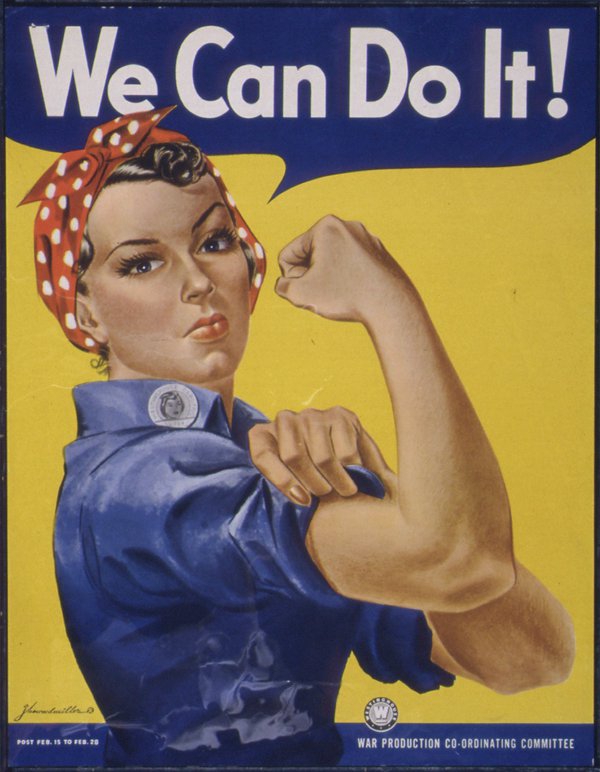

Late in 1942, Pittsburgh artist J. Howard Miller produced a painting for the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. The image of a female worker in denim coveralls and a red-and-white polka-dot headscarf, with a Westinghouse employee identification badge pinned to her lapel, was reproduced on posters for display inside the company’s munitions factories. Miller’s image had a limited and largely private run, appearing on Westinghouse shop floors over a two-week period from February 15-28, 1943, before the company tacked up the next in a series of his paintings. Like the “We Can Do It!” poster, below, each painting bore a different message intended to increase production, boost morale, avoid absenteeism or prevent strikes. Beyond the Westinghouse factory walls, however, the bandanned woman remained unknown. Miller’s subject was also unnamed, but not for long.

Also in February 1943, a song written by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb and sung by The Four Vagabonds hit the American radio airwaves. “Rosie the Riveter” told a story happening across the country: Women were going to work in record numbers, doing jobs unlike those they had ever done. “All the day long, whether rain or shine,” the lyrics went, “she’s part of the assembly line/She’s making history, working for victory/Rosie the riveter.” According to Loeb’s widow, no single woman inspired the song; the name Rosie was chosen for its alliterative appeal. In the naming, though, an American archetype was born.

By the time artist Norman Rockwell painted what became the Saturday Evening Post’s May 29, 1943 cover, Rosie was a well-known character; a hard-working, patriotic woman. On her lunch break from the assembly line, she sits denim clad with a rivet gun on her lap. To complete his composition—which Rockwell said was based on Michaelangelo’s Sistine Chapel painting of the prophet Isaiah—Rosie stood atop a copy of Mein Kampf, so stamping out fascism with her own might. The U.S. Treasury Department’s subsequent use of Rockwell’s art to advertise war bonds ensured that his was the image Americans would identify with Rosie the Riveter throughout the war.

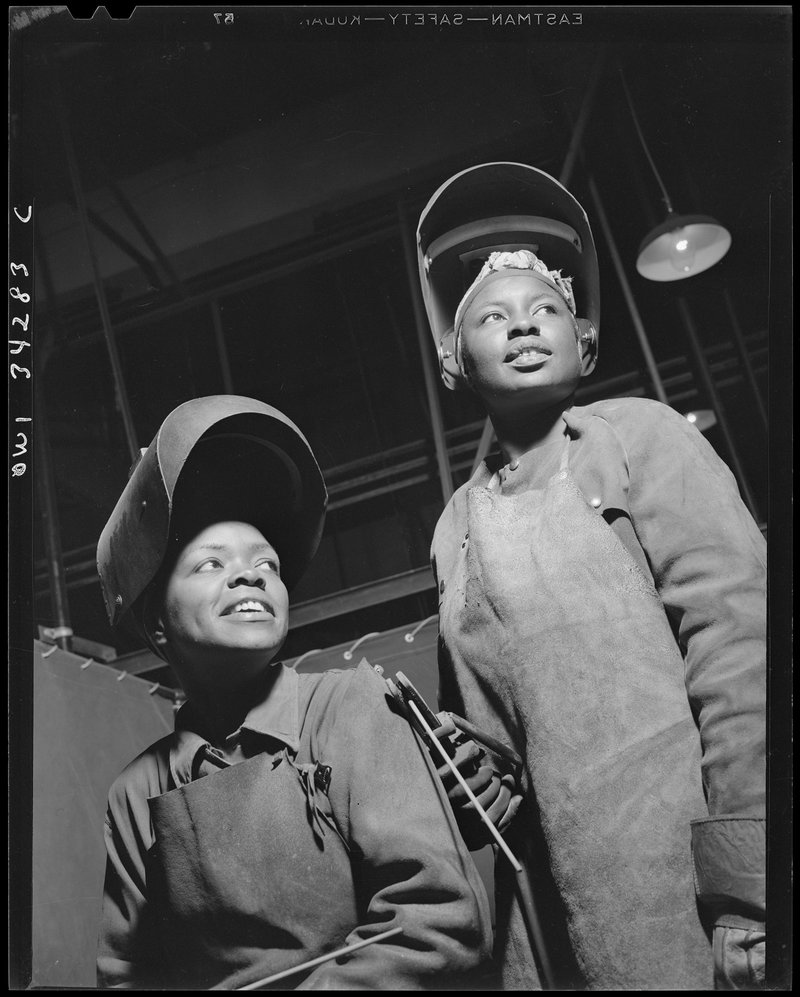

Miller and Rockwell both depicted only a carefully selected vision of who made up America’s wartime labor force, though. Black women worked by the hundreds of thousands during the war but were unacknowledged by government and the mainstream media. “Rosie the Riveter is classic propaganda 101,” says historian Emma McClendon. “You've got this woman going to work, helping the war effort, and what is she wearing? A blue denim jumpsuit and a red bandana—and she's white. So in that sense, she becomes this icon of America, of the red, white and blue.”

The OWI did not represent the diversity of women who were doing war work, but its recruitment campaign was a success. “There are practically no jobs, it has been found, that cannot be adapted for women workers,” Newsweek reported in August 1943. “They are in the shipyards, lumber mills, steel mills, foundries. They are welders, electricians, mechanics and even boilermakers. They operate streetcars, buses, cranes and tractors.” In March 1941, 10.8 million women in the country were employed; by August 1944, that number had risen to 18 million. Still, women uniformly received lower wages than men for the same work. And when the war ended, women were the first to lose their jobs to returning veterans.

Miller’s poster wasn’t widely associated with Rosie for another four decades. From the 1980s onward, the “We Can Do It!” image proliferated, finding its way into pop culture via a raft of reproductions, from advertising and bobblehead dolls to political campaigns and postage stamps. Originally created only for an internal public service announcement, Miller’s art became a broadly recognized feminist icon. Contemporary portrayals of Rosie have also been more inclusive, imagining a wider range of identities—so, too, expanding who may embody Evans and Loeb’s lyrics: “there's something true about/Red, white, and blue about/Rosie the Riveter.”