Reporting Ruby Ridge

An Interview with Jess Walter and Bill Morlin

By Cori Brosnahan

At the time of the 1992 Ruby Ridge standoff, Jess Walter and Bill Morlin were reporters for the Spokesman-Review in Spokane, WA — the closest large city to the ridge. Morlin was a veteran reporter who had been covering the radical right in the Inland Northwest for over a decade; Walter was newer to the newsroom, and would go on to write Ruby Ridge, the definitive book about the standoff. American Experience spoke to them about what it was like to report the story on the ground and in the months and years after. Here are excerpts from that conversation. The text has been edited for length and clarity.

On the beginning of the standoff:

Bill Morlin: We were in the newsroom and we heard that shots had been fired at the Weaver cabin. I believe I got a phone call from a federal source that tipped us off to that. I alerted my editors. A photographer and I immediately raced for the airport and chartered a fixed wing aircraft to fly over the cabin to find out from the air what was going on. So we got in the air over the cabin and got the only photographs that were actually obtained because shortly thereafter the federal authorities closed the airspace.

I was in the backseat of the aircraft and the photographer was in the front right seat. I was actually holding open the window as this pilot did these power figure eights over the cabin. I had an earpiece from local law enforcement in one ear and a mouthpiece to the pilot in the other, and all we could see was two or three police cruisers on the ground in the distance with their light bars flashing — we couldn’t really see any individuals on the ground. At one point I did hear it mentioned over the scanner, ‘They’re shooting at that aircraft.’ At that point, I asked the pilot to promptly get us out of there. Fortunately, the people on the ground didn’t hit our aircraft. And, of course, they had no way of knowing who was inside — they might have very well thought it was the FBI or the ATF — they had no clue it was two members of the news media. We’d already taken some shots, so we landed the airplane and the photographer rented a car and drove back to what turned out to be the roadblock. I drove on to Spokane with the film and wrote the story, then returned to the roadblock later that night.

On watching things escalate:

Bill Morlin: The first night that I got there it had been warm weather and suddenly that night it starts turning cool and starts raining. I brought a cooler with me and a pillow and no sleeping bag, but I should have. So I ended up sleeping in the back of my SUV at the roadblock. And I remember I didn’t get much sleep because all night long, I’m seeing FBI vehicle after FBI vehicle come rolling in. And by the next day, I’m seeing military-style vehicles — not armored personnel carriers, but Humvee type vehicles — and I think there actually might have been an armored personnel carrier that rolled in there. And it was like, wow, this is turning into a big deal. And then as it unfolded from — that was Saturday morning so all day Saturday and into Sunday and into Monday there was just a huge influx of people at the roadblock. The networks are showing up with their satellite trucks. You have to keep in mind also that this is in a pretty rural part of the country and really before cell phones had become what they are now, certainly, and our computers were nothing compared to what they are now. I think we had Trash-80s, Jess?

Jess Walter: Yeah, we had Trash-80s. I think when I originally arrived we had reporters out doing so much reporting and every night we were just filing right on deadline, with reporters feeding notebooks to each other. And the story was changing faster than a lot of things that certainly I’ve ever covered. There were protesters arriving — there was a truck full of skinheads that arrived possibly with weapons — the whole thing was moving so fast. Even in those early days it was a strange thing to cover.

On tracking down the Weavers’ families:

Jess Walter: I wasn’t assigned to the story at first. There were four reporters already on the scene. Like a lot of young, aggressive reporters, I wanted to be on the story. So I stayed in Spokane and started working the phone. All we knew was that Weaver was from Iowa. So my goal was to see if I could get more information about Randy Weaver when he’d been in Iowa. I’d heard that he’d worked at a John Deere plant, so I began going through phone books, Iowa phone books. I’d call libraries and have them look through their phone books and tell me which towns had John Deere plants, until I found a cousin. That cousin led me to another cousin, who led me to Vicki Weaver’s family. I got them on the phone—and they had not heard from the FBI or the Marshal Service or anyone—so they had as many questions for me as I had for them.

On logistics:

Bill Morlin: Because of the remoteness of this, early on, I realized that we needed to have some kind of shelter. Fortunately, about a mile away we found a farmer who had a barn that he’d converted into kind of a granny pad. There were a few beds and I guess running water, but it was pretty crude. But I figured gosh, we need to have a place where we can lie down at night and set up some kind of shift operation because basically we needed to have somebody — a reporter, a photographer, or both — at the roadblock 24 hours a day because we never knew when this thing was going to end or how it was going to end.

We had a crude radio system of two-way radios so the person at the roadblock could talk to the rest of us who were back at this makeshift barn operation. The editors, at my urging, installed a landline — which was fairly expensive, actually — because we had to hook up our modem to get our stories out of there. This is 25 years ago. I wish we had the technology we have now — we could have been skyping the whole thing. It was a pretty rudimentary operation.

On reporting in the dark:

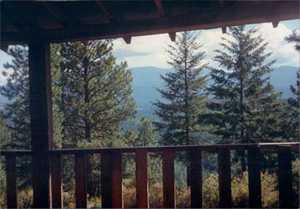

Bill Morlin: You have to remember that where the roadblock was, no one could see the cabin. The cabin was two miles up this narrow wooded road in the hills of North Idaho. We were given daily briefings finally by an FBI agent, but it was never a lot of information. So everybody’s wondering what’s going on. It was a government conducting an operation in the dark and the media wasn’t really being told what was going on.

On the first shift in the narrative:

Jess Walter: More armed agents would show up at the roadblock right before they would have one of these announcements. Gene Glenn, the special agent in charge, would gather the reporters and tell us, this is what we found. In the Northwest, there had been this series of stories about white separatists and white supremacists committing crimes and causing problems, and I think Sammy’s death was the first shift in the way, certainly as a newspaper, we were covering this story. It wasn’t the same old The Order or The Order II, this was going to be a much more complex case. It was becoming clear once we found out that this wasn’t an ongoing firefight where a deputy marshal had been killed only, that there had been another victim, that someone else had been shot and it had been Sam Weaver, Randy’s son.

As reporters, I think you have to step back and look at the normal narrative and begin asking more questions of the sources that are giving you this information. The other hard thing is that you have gathered at this roadblock people who are spreading all kinds of conspiracy theories. They’re telling you that they’re going to dump gasoline on the Weavers and that there are black helicopters flying by. It was a pretty intense scene. An armored personnel vehicle would drive by and [protesters] would run up to the window and scream, ‘baby killers!’ And I had one group of protesters insist that I was an FBI agent because of my car. It was a company car that I had borrowed from the newspaper. It was a four-door sedan and they were certain I was an FBI agent because I was a fairly young guy driving this four-door sedan.

On the second shift in the narrative:

Jess Walter: I think the most dangerous point, the point when it felt like it was going to erupt in violence, possibly, was toward the end of the standoff when Bo Gritz and Jack McLamb returned from talking with the family, and the FBI gathered the reporters and announced that Vicki Weaver had been killed. I don’t know if you remember, Bill, what a tense night that was. That felt like a double blow. The FBI had said this is an ongoing firefight, marshals are pinned down by neo-Nazis — and to have it all of the sudden be, no, their 14-year-old son is killed and, oh, also the mother was killed earlier on in the standoff. The narrative had changed so completely.

On the difference between national media and local media:

Jess Walter: I would say the big thing is that [the national media] leaves. They show up, they haven’t done any of the early reporting, and then they go home and go on to the next story. I think as a reporter in a market this size, you’re used to being poached, people taking the information you’ve worked hard to report and then reporting it and then just disappearing. For me, the standoff was only the beginning. I kept covering the case for the next few years, trying to figure out how the Weavers’ belief system developed, following through to the trial. And I think what Bill said earlier about other media not really covering white supremacy cases in the Northwest was doubly true of Ruby Ridge. Once it was over, national media — all those reporters who were here from NBC and the Wall Street Journal — they went on to other stories. And it was really the Spokesman-Review — we kept up our coverage for the next couple of years, all the way through the trial and beyond.

Bill Morlin: In September of 1995, the senate judiciary committee called a hearing into the events and circumstances surrounding the Weaver case at Ruby Ridge. And the story was on the front page of Newsweek. Here it is three years after the event and the national media is finally paying it attention. By then Jess’s book had come out. And, of course, that was also after the Oklahoma City bombing where 185 or so people were killed, and all of a sudden, the risk presented to the rest of us by these domestic terrorism issues was finally grabbing hold of the American psyche.

On learning the other side of the story:

Jess Walter: I think it surprised me completely. I began as a sort of support reporter on this case, and came in after the standoff had started, following Bill’s terrific reporting and the other great reporters who were working up there—we had just an amazing team. But the question I kept asking myself was, how did a family of people, these god-fearing people from Iowa who joined the army and want to run for sheriff and appear sort of all-American—how do they end up on a mountaintop believing the world is about to end, fighting the government? Partly because I’d gotten to know the family, the day the standoff ended I asked them, I’d love to interview Sara Weaver afterward, and they said, okay, but only you and only at 7 o’clock tomorrow morning. I wasn’t allowed to tell anyone else, I wasn’t allowed to bring a photographer or anything, but I was able to interview Sara and Rachel Weaver with their family present. And they gave the first glimpse of what it had been like in that cabin. It was the first time we’d had the other side of the story about what had happened up there.