Ruby Ridge, Part One: Suspicion

The story of the 1992 standoff that helped launch the modern militia movement.

By Cori Brosnahan

To tell the story of Ruby Ridge — a standoff between the federal government and the heavily-armed Weaver family in the remote hills of Idaho — filmmakers Barak Goodman and Emily Chapman interviewed eye witnesses, including federal agents on the ground, journalists who reported the story, and a member of the Weaver family. This three-part narrative draws directly from the transcripts of those interviews, exploring how a seemingly small infraction — failure to appear in court for sawing off shotguns — escalated into a tragic standoff that ignited a powder keg of tension, and served as a calling card for the modern American militia movement.

Read Part Two here and Part Three here.

Jess Walter, 1992

Theirs had been a traditional love story in the heartland. Randy Weaver grew up playing Little League in small-town Iowa. Later, he attended a few years of community college in Fort Dodge, where he spent nights cruising the streets in his Mustang with friends. He dropped out to join the Army and became a Green Beret. Vicki Weaver was raised on a farm and could sew, cook, knit — you name it. In high school, she was an A student, and an enthusiastic member of the Pleasant Valley Pixies 4-H. After they were married in 1971, Randy took a job at a John Deere tractor factory and Vicki worked as a secretary at Sears. They settled in Cedar Falls in a tidy, white and brick house on a pretty, tree-lined street. Soon they had three children: Sara, Sam, and Rachel. By all accounts, they were an attractive, gentle couple who looked out for their neighbors.

How, reporter Jess Walter would wonder after it was all over, had a couple of all-American kids ended up on a mountaintop in remotest Idaho, armed with guns and the belief that the U.S. government was going to kill them? And how had it come to pass that they were right?

Now, Walter was talking to their family and friends, looking for answers. Randy and Vicki Weaver, it turned out, had been looking for answers, too.

The 1970s were giving way to the 1980s and times were tough. The economy was collapsing; interest rates were up 15, 16, 18 percent; farmers were losing their land left and right; and gasoline was ungodly expensive.

The Weavers, thought Walter, were seeking to understand a world that seemed out of control. It led them to evangelical preachers on television — Jerry Falwell and the PTL Club — and to books like Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth, which explained how you could interpret current events using the Old Testament.

To Randy and Vicki Weaver, Lindsey’s book really did seem to explain it all: Gog, the evil empire discussed in Ezekiel, was actually the Soviet Union; the ten horns of the beast from Revelation were the ten nations of the Common Market of Europe; and the global increase in famine, war, and earthquakes was a sure sign of the apocalypse to come. Randy and Vicki Weaver were trying to connect the dots. And what the dots told them was that the world was about to end.

Concerned citizens, they set out to spread the word. They were unable to find a church that approached these matters with what they felt was the appropriate level of seriousness, so they held their own bible studies with like-minded friends and neighbors. This sparked the attention of a local reporter, who came to do a story on them. The Weavers, Walter learned, did not appreciate the results — they felt betrayed. But they had never been more sure in their beliefs. A great conflagration was coming and they felt increasingly unsafe in Iowa. Vicki started having visions in the bathtub. God was speaking to her. And God was telling her to go West, to find for her family a mountaintop. They would be safe there.

Sara Weaver, 1983

Sara Weaver was seven years old when her family moved from Iowa to Idaho. She had been happy in Cedar Falls. There were hot Iowa summers, where you’d fill up the pool in the front yard, and cold Iowa winters, where you’d build snow forts in the backyard. But when her parents told her they were moving to the mountains, Sara was more excited than anything else. Her father said they’d get a horse and chickens, have a pot of chili on the stove all the time, climb in the mountains, and fish in the creeks. It would be an adventure, and it sounded fun. It sounded like you’d be on vacation all the time. Her mother would be her teacher and Sara was fine with that. She adored and admired her mother.

Sara knew that her mother had a very strong desire to please God. Sometimes this manifested itself in specific ways, like when the TV went away. She knew that there had been a rift with a local church and a write up in the paper, and that her parents were very hurt by it.

They started having garage sales to sell their stuff and buying new stuff that they would need when they moved to the mountaintop. They visited the Amish to learn how to live without electricity and running water. Sara thought the Amish kids were super-quiet and nice. She liked the oil lamps they used and was impressed by the little crocheted purses made by girls her age. She felt it was very peaceful amongst the Amish.

It was sad to say goodbye to her grandparents, and a little chaotic when they took off because Sara’s brother Sammy decided to jump off the back of the truck and break his leg, and they had to make an emergency run to the hospital to get a cast on. But Sara propped her brother up on pillows in the cab of the truck so he’d be comfortable, and soon they were on their way.

They were a week on the road, stopping to do family things like visit Reptile Gardens. The truck was so heavy with all the supplies they’d packed, that they had to stop and unload and bless some needy families. They stayed a while in Bonners, Idaho while her parents looked for land.

The first time they went up to Ruby Ridge was like a carnival ride. They came from the flatland, from a little square of grass and concrete sidewalks, and this was a big, wild, rocky mountain, which was quite different. So Sara’s mother covered her eyes and the kids bounced around in the back of the truck, and it was an adventure just getting up there.

Life on the ridge was pretty great. There were so many things for Sara and Sam to explore and learn and just do every single day. Of course, they worked hard, too, but they were never scared of working. They did dishes and split firewood and hauled water. Sara looked after her sister Rachel, who was just a toddler when they moved to Iowa, and helped her mother do the laundry—first with a washtub and a washboard, and, later, after her grandpa visited and saw the way they were living, with a gas-powered wringer-washer. She also helped garden. Sara loved to garden.

Sara’s mom had a knack for making wherever they were feel like home. She sewed curtains and made cushions and even stained the cabinets. Sara thought the cabin was pretty cozy, with three sleeping rooms upstairs and a kitchen with a pantry and a living room downstairs. There were two couches and two really nice chairs for Sara’s mom and dad, and big braided rugs on the floor. It was a good room to read in, which they did constantly, sometimes two books a day.

Sara didn’t feel too separate from the rest of the world. In the summer, she picked huckleberries and went garage saling with her mother. She made friends with a girl who lived in the area and they saw each other a good bit. But her most constant companion was Sammy. They played card games, Monopoly, Risk, and Scrabble all through the long evenings, all through the long winters when the wind blew fiercely outside the little cabin on the hill.

All in all, it was a nice life.

Bill Morlin, 1987

The first time reporter Bill Morlin heard about Randy Weaver was when Weaver ran for sheriff in Boundary County, Idaho in the late ’80s. Morlin hadn’t covered that particular election, but Weaver was kind of a high profile candidate, handing out these flyers that said, ‘If you elect me, I’ll give you a card that says get out of jail free.’ Of course, that was the kind of thing that interested people. Morlin also thought that some of the profile stories on Weaver suggested he had ties to the Aryan Nations. Morlin covered the Aryan Nations, so this was of special interest to him, and he tucked away the name ‘Randy Weaver’ the way reporters tuck away names they expect might turn up again.

Morlin had started covering the Aryan Nations in the early ’80s, after the group held a cross burning in North Idaho. Rarity makes news. Cross burnings were a rarity in the inland northwest, and Morlin was assigned to find out what was up with this group, who they were, and so forth.

What he found out was that a former aerospace engineer from the Los Angeles area named Richard Butler had moved to North Idaho in the ’70s. He bought a 20-acre compound there in Hayden Lake, just outside the tourist town of Coeur d’Alene, where he founded the Aryan Nations. Butler and his immediate followers were members of a religious group called Christian Identity, which held that white Christians were the real, true Jews, the children of God, and that the people who called themselves Jews were imposters and seeds of the devil, and that people of color were mud people who denigrate everyone else, and so forth.

Every July, Butler hosted the Aryan World Congress, which drew hundreds of fellow white separatists and white supremacists and racists of various stripes. Some of them were Ku Klux Klan. Some were Posse Comitatus. Some of them didn’t believe in God. Some of them did believe in God. Some of them were outlaw bikers. Some of them wore camouflage. A lot of them hated the government. But the idea was to come together and break bread, to get to know each other and to network.

One of the people networking at Hayden Lake in the early ’80s was a young man from Arizona named Bob Mathews. Mathews had been in trouble with the IRS and had a great hatred for the government. He also had a great urge to act upon that hatred, and believed that Aryan Nations founder Richard Butler was all talk. Others at Hayden Lake agreed. Mathews said the time had come for action and founded his own group. He called it The Order, after the fictional entity in the 1978 dystopian novel The Turner Diaries.

Like that fictional entity, Mathews and his followers were of the opinion that Jews were taking over the country and if they didn’t act, the white race was doomed to failure. So the dozen or so members of The Order declared war on the United States. To finance their campaign, they started counterfeiting money, and when that didn’t work as well as they wanted it to, they turned to robbery. Their first outing was modest, stealing $369 from an adult bookstore in Spokane. But soon, they were targeting banks and armored cars to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars. In June of 1984, they bombed a synagogue in Boise. Later that month, they assassinated an outspoken Jewish talk show host named Alan Berg in Denver.

It was domestic terrorism. Of course, that wasn’t how folks talked about it then. Most people didn’t even know what “terrorism” meant. The FBI wasn’t even necessarily aware that people with this sort of agenda were out there, ready and willing to rob banks and take lives. After all, when Richard Butler opened up shop in 1981 and burned the cross in North Idaho, there was just one FBI agent in Coeur d’Alene. So for a long time, The Order wasn’t really on the Justice Department’s radar.

It wasn’t until The Order robbed an armored truck in Ukiah, California, making off with $3 million, that the FBI started to pay attention. Now they had to play catch up. Morlin remembered going into a federal office, where he saw a spread of pictures — big pictures, small pictures, color, black-and-white, driver’s licenses, mug shots — essentially a who’s who of The Order. The FBI was trying to figure it out. Who were these people? Where did they come from? What were they trying to do?

In those days, there were times when he, Morlin the reporter, was in virtual lockstep with the agents. On one occasion, he had learned where some of The Order money was hidden, and got a call from a senior Justice Department prosecutor asking him to hold that story because they weren’t going to get a search warrant to go after the money until the next day.

The big break came when a member of The Order couldn’t resist using counterfeit cash to buy lottery tickets in Philadelphia. He made the mistake of going to the same place twice. He was arrested and, in short order, flipped. The informant led authorities to the Capri Motel in Portland, Oregon, where members of The Order, including Mathews, were hiding out. A gunfight ensued, but Bob Mathews escaped.

Matthews and several followers fled to Whidbey Island, a remote place on Puget Sound, west of Seattle, with the FBI hot on their trail. Multiple SWAT teams were called in. Agents managed to convince everyone to surrender — except Bob Mathews.

They knew he was heavily armed. They tried to smoke him out, but it didn’t work. Then they brought in a helicopter to fly over the place and look it over, and Mathews opened up on the helicopter. Agents fired back, but Mathews kept shooting, opening up on one side and then the other. It went on like this for 36 hours. It started to get dark. The agents got anxious. They launched some illumination rounds into the house and it caught fire — the cabin started to burn. But no one came running out. When they finally went in, they found the charred remains of Bob Mathews in a bathtub.

The feds hadn’t been expecting that level of dedication, that kind of fanaticism, and Morlin thought Whidbey Island shook them up. They’d been surprised by Bob Mathews and The Order; they would not let themselves be surprised again. By the early ’90s, Hayden Lake was crawling with federal informants. Both the FBI and the ATF were regularly conducting investigations. You might have a meeting of three suspected white supremacists in a car, and two of them would be government informants. They’d all be listening, unbeknownst to each other.

Sara did not necessarily share her parents’ views about the whole religious aspect. She wasn’t into the Bible, never spent much time reading it. But she went along with it because she wanted to please her parents, because she loved and respected them and wanted to do the very best she could no matter what her personal feelings were. As the oldest child, she had always been that way.

In those days, Sara’s parents spent a lot of time researching the roots of words and where they came from, especially in the winter, when the nights stretched on forever. Yaweh and Yashua, for example, were the Hebrew names for God and Jesus, respectively. They shared what they learned, but always said not to believe it just because they said so. They didn’t want to push anything on her. They encouraged her to research it for herself. That was the way they were.

Sara’s Dad, especially, liked a healthy debate. He was outspoken and opinionated, but friendly and inquisitive. Later, Sara would say that was probably why he’d gone to check out Hayden Lake in the first place — just to meet people and find out what was going on over there.

Sometimes the whole family went on trips to Hayden Lake. At the Lake, there were tons of kids you could play with. There was picnic food, bonfires and games for the children. There was watermelon and little gift bags. They camped in a tent and had some good family time. They also met other people in the community. Sara’s dad had befriended a man named Frank Kumnick, who introduced him to more people, including a man named Gus Magisono. Sometimes, Frank and Gus and their families would come to Sara’s house and have dinner, and other times Sara’s family would go to their houses for dinner. They were friends. Later, Sara thought she even remembered Frank ending up with one of their dogs.

When reporter Jess Walter finally got to listen to the wiretaps, it was pretty clear to him that Randy Weaver was never the target, but had been identified as someone who could possibly be used as an informant. It was easy to see why: Weaver was a veteran, had run for sheriff, and didn’t seem to be a criminal. On top of that, his beliefs didn’t seem to be as race-driven and as ingrained as the beliefs of other people hanging around Hayden Lake.

There were Randy, Fred Kumnick and the 245-pound biker Gus Magisono meeting to talk about their plans. Only, Randy Weaver didn’t seem to have any plans. He didn’t seem to want to start a race war or commit crimes. In fact, he often distanced himself from that agenda, saying things like, “We have a more religious view of these things” and “we don’t go in for this kind of stuff.” Frank Kumnick, for his part, wanted to explore things along the lines of fraternity pranks. He wanted to put epoxy glue in the doors of banks and strip federal agents naked and make them walk home. Randy Weaver wasn’t interested in any of that either.

As Walter saw it, the Weavers really did have their own personal ideology; it bumped up against Christian Identity and the kind of stuff people believed at Hayden Lake, but didn’t quite match. Later, for example, he’d meet people who swore that Randy and Vicki Weaver didn’t have a racist bone in their bodies. Still, there were similarities.

Sara’s dad had taught her and her brother Sammy how to shoot a BB gun around the age of seven, and moved them onto .22s a few years later. He showed them how to carry a gun and how to clean one, and he was very, very strict about their use. You did not play with guns like toys; every single one is loaded, whether you unloaded it or not. Guns were there for a purpose and that was for protection from wild animals or to hunt meat. In other words, they were tools.

Sectional views of a Remington Model 870 pump action repeating shotgun. Under the National Firearms Act (NFA), it is illegal for a private citizen to possess a shotgun with a barrel length shorter than 18 inches (46 cm) or an overall length shorter than 26 inches (66 cm).

Sara’s dad even used them as a savings account sometimes. He would buy a gun when he had extra cash, and sell it off next time they needed money. And they needed money a lot in those days. It was not easy to get to a job from the ridge, not easy to do the nine-to-five thing. Sara’s dad worked several different jobs, but it was tough to support a family of five — six when their friend Kevin Harris was staying with them. So if he had an extra gun and someone was interested, he’d sell it and then they’d go buy groceries. Someone, Sara would later think, must have picked up on that; they had sure taken advantage of it.

As Walter learned, Gus Magisono — who turned out to be the government informant Ken Fadeley — would eventually testify that he had become nervous his companions would figure him out and didn’t always wear the wire. Consequently, he had failed to tape some of his meetings with Weaver and Kumnick — including the fateful one in which they had determined where the shotguns would be sawed off and how Weaver would deliver them. Fadeley had simply gone back to his ATF handlers and told them that Weaver had agreed to do it. It was therefore unclear whose idea it had been. Entrapment, Walter thought, was a judgement call, like pass interference in football or charging in basketball. But the journalist felt it was pretty clear that Randy Weaver was not the kind of guy up there sawing off the barrels of shotguns and selling them, that he needed money and had only committed this crime once — after talking to an undercover ATF agent.

The government had wanted Sara’s dad to become a snitch. They told him that they would have dropped the gun charges. But Sara’s dad had integrity and a code of ethics that did not include taking your fellow man down in a sneaky manner.

“I told him where he could go,” Sara heard her Dad say. “I’m not into doing that.” Of course, Sara knew that you could not make her father do something he didn’t want to do. That was just who he was.

Law enforcement had unknowingly confirmed the Weavers’ worst fears, their most paranoid and conspiracy-driven beliefs, Walter would think. The Weavers believed that the end of the world was coming. And that it began with government treachery.

The stuff with her dad and the federal agents had rattled 14-year-old Sara’s little world. But there was so much to do up on the ridge — it was a full time job just to survive — so you did what you had to do and moved on.

Months passed, and then, in January of 1991, Sara’s parents were driving to town when they stopped for a couple with a broken-down truck. They got out of the car and were thrown faces-first into the snow. They were frisked and Sara’s dad was hauled off to jail on federal firearms charges. He had to post their home as bond to get out. And when he came back, he told the family that if he lost his trial, they’d lose their land.

In fact, Jess Walter learned, the magistrate had been mistaken when he told Randy Weaver that if he lost his case, he could forfeit his property. That was not how an unsecured bond worked. Later, Walter would wonder whether that little piece of misinformation made the difference. The Weavers had moved to Idaho to keep their family safe. And now they were being threatened with the loss of the very mountaintop they saw as their salvation. Would they have come down otherwise? Of course, it was impossible to say.

Sara’s family had always made decisions together. So after the arrest, her parents sat everyone down at the table to discuss the situation. What do you think we should do? they asked the kids. The kids said that they didn’t want their dad to go to jail, they didn’t want their mom to go to jail, and they didn’t want to lose their house. They talked it over, and the general consensus was that since no one knew what to do, they weren’t going to do anything. They’d just stay put until the whole thing got figured out. Surely, there would emerge a voice of reason.

“You’know,” Sara heard her dad say, “If the Sheriff would come up and knock on my door, I’d invite him in for coffee, and we’d sit down and have a discussion.” Sara’s dad was upset about getting thrown in the snow and the way he had been treated in general, and he wanted an apology.

So they stayed on the mountain, waiting, Sara thought, for the lone ranger.

Dave Hunt, 1991

When U.S. Deputy Marshal Dave Hunt asked people who knew the Weavers if he shouldn’t just go up to the mountain and talk to Randy Weaver, he usually got some kind of laugh in response. Out of the several dozen people that Hunt interviewed, not one thought it was a good idea — in fact, they all said it would be the worst thing he could do. Weaver, they said, was committed to his cause. And so were his kids.

Hunt had been in law enforcement for 20 years by that time. A former Marine, he’d started off in local enforcement, and then applied to the Marshal Service, which he described as “the sheriffs of the federal government.” As such, marshals had a range of responsibilities — everything from fugitive hunting to the witness protection program. If you wanted to get formal about it, they were the enforcement arm for the judiciary, and carried out all precepts and orders of the federal court and other duties as assigned by the Department of Justice.

To become a marshal, Hunt had taken all kinds of tests — intellectual and physical; he’d had to score high enough to be accepted at each level. He went through criminal investigation school and then the U.S. Marshals Academy in Glynco, Georgia.

After graduating, Hunt was sent to Alabama, where there was a lot of action due to the Civil Rights Movement. It was the first time he’d been south of the Mason-Dixon in his life. There he was assigned to the protection detail for the first black judge appointed in Montgomery. On that job, he met a deputy, a black man, who had been with Ruby Bridges, the bravest little girl in the world, when she walked to school in New Orleans in 1960. It was the event memorialized by Norman Rockwell in that famous painting, which included several marshals, identified by their yellow armbands. The deputy, who was about to retire, had been one of those marshals and had one of those armbands. He was sitting across from Hunt when he pulled it out and asked if the young marshal wanted it. Hunt said he would like that, and the deputy threw it across the table. Hunt would mount the Norman Rockwell picture on the wall in his office, and, right below it, the deputy’s yellow armband.

After Alabama, Hunt had worked all over the country. He guessed he’d only missed a couple of states. But primarily he worked in Idaho, where he ran the district’s enforcement section.

The first time the name Randy Weaver crossed Hunt’s desk was after Weaver failed to appear in court and the federal bench issued a warrant for his arrest. Hunt took a look at Weaver’s case file and did some investigating to find out what the guy was about. He wasn’t anything too unusual. Hunt had seen this kind of thing before. He might not run into such radical ideology on a daily basis, but with the Aryan Nations right up the road, he certainly ran into these types on a monthly basis. He felt he had a fair amount of insight into what he was looking at.

Hunt did all the threat assessments for the Idaho area, and he set about creating one for the Weavers. The purpose of a threat assessment was to sort fact from fiction and determine how much trouble law enforcement could expect. Of course, you always hoped there wouldn’t be any at all.

The threat assessment for Randy Weaver showed that he and his wife were driven by a number of religious and political beliefs that were very influenced by the Old Testament. Vicki Weaver appeared to be the leader; people told Hunt that at prayer meetings, Weaver would turn to his wife and say, ‘How do we believe?’ or, ‘What are our thoughts on that?’ And she would tell him how to respond. But both were extremely committed to their cause; they would, Hunt thought, lay down their lives for it if necessary.

Below are three pages from the threat assessment Dave Hunt compiled on Randy Weaver.

Hunt’s threat assessment also showed that Weaver had been further radicalized after being tricked and arrested, which led him to conclude that everything he believed about the federal government was coming true. This made him a little more dangerous, but Hunt wasn’t worried. Even after reading a letter Vicki Weaver had sent the U.S. attorney’s office threatening that “The tyrant’s blood will flow,” along with another message, passed to him by one of Weaver’s neighbors, that read “Whether we live or die, we will not obey your lawless government,” Hunt stayed pretty calm. He had dealt with these kinds of people before without big problems, without violence.

Hunt’s mission, then, was to put a human face on the Marshal Service, and, by extension, the federal government. If possible, he had to develop some kind of rapport with Weaver — not to be judgmental, which, in Hunt’s estimation went to the very core of the Marshal Service. Marshals may carry out the percept of the court, but they were not judges themselves. For all Hunt knew, the man wasn’t even guilty. His research had also shown that Randy was a very social person. Surely it wouldn’t be long before he came down.

So Hunt would be patient, wait it out. He did not see any reason to hurry.

Bill Morlin, 1992

It was 1992 and Bill Morlin was at the Spokesman-Review, where he was still covering extremists. On a daily basis he was checking in with federal law enforcement sources to find out who they’d arrested and what their deal was. And so he’d found out that the ATF had arrested Randy Weaver, the former candidate for sheriff with possible ties to the Aryan Nations, on federal firearms charges. Weaver, it seemed, had been caught sawing off a couple of shotguns. It was fairly routine.

But then Morlin began to hear things that made his journalistic instincts perk up. Weaver had failed to show up for his court date, which meant the Marshal Service had been called. Now there was a fugitive up on a hill in Idaho, refusing to come down. Law enforcement believed he was a white supremacist. And, according to Morlin’s sources, the marshals had no clue how they were going to get him down without a big gunfight. Weaver was heavily armed, as was his wife, as were their kids — who, the marshals believed, had probably been brainwashed into thinking that the federal government was the enemy. The kids were a big problem. No one wanted to get into a gun battle with kids. But this was a country of laws, and the Marshal Service was under an edict from a federal judge to do their job. They had to get him down.

Morlin decided the situation had all the pathos of a rich American story and he decided to pursue it. His line editor said he didn’t see what the story was, but like any veteran reporter, Morlin had learned how to run an editor.

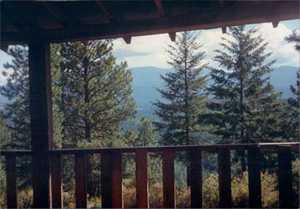

He continued to investigate. He learned that the agencies were in a real quandary over how to handle the situation. Some were advocating a front-on tactical assault, while others argued for a ruse, dismissing the charges so Weaver would come out, at which point they’d refile. He learned that these things were being discussed at the highest levels, that it went clear back to Washington, D.C. He learned that the Marshal Service was flying FP4 jets equipped with cameras over the Weaver cabin to map out its location in relation to the surrounding geography. He got to see one of these photographs taken from the FP4, a little three-by-five snapshot. There it was: this tiny little dot of a cabin surrounded by mountains and green forests. It was a striking image. But it belonged to the feds. So Morlin took the picture to the Spokesman’s photo editor, who was duly impressed. They would rent a plane and get a picture of their own, the photo editor said. Morlin would accompany the photographer.

And so, late in February of ’92, Morlin was sitting in the back seat of a Cessna flying over Ruby Ridge, holding the window open so the photographer could lean out and get a clear shot of the Weaver cabin. They went back to Spokane with some terrific photos, which really sealed the deal. The editors were now on board. Tail wagging the dog. Boom: Sunday, page one, March 1992.