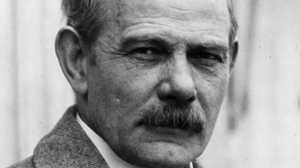

John Boland

"It seems to me that my major accomplishments, if any, were the nine years that I conducted the business affairs of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial Society." — John Boland

John Boland, a local businessman, was Gutzon Borglum's nemesis in the creation of Mount Rushmore. This was true despite the fact that Boland and his wife had been to dinners at the Borglums', and despite Boland's steadfast support of the Rushmore project.

John Boland was born in 1884 in Keystone, South Dakota. He went to engineering school for two years before buying his father's general store. That first foray into business failed and led him to business college. His next store was more successful, but was burned in a fire in 1917. Boland then bought the Rapid City Implement Company and sold farm equipment, cars, and large appliances to farmers. His business sense won him respect, and his empathy for his customers -- extending credit to the farmers and ranchers hardest hit by the Dust Bowl and Depression — won him loyalty.

Boland was mayor of Rapid City when Borglum first came to the Dakotas and made a speech describing the proposed monument. Boland told his wife, "I heard a pretty attractive proposition tonight. If we can pull it off it might be a great thing for the Hills." Boland was an early supporter of Rushmore, boosting it as mayor, and even contributing $50 to Borglum's first expense check. He led the local Black Hills fundraising drive and even pledged to guarantee any pledges that were later reneged.

The Rushmore appropriation bill signed by Calvin Coolidge in 1929 required that a Mount Rushmore National Memorial Commission be formed. John Boland was named the president of the executive committee of that Commission. In that position, he became a general manager of the project, responsible for all the finances. This was reinforced in 1933 when the memorial was placed under the National Park Service. Boland was to make sure that all of the Federal funds allocated to Rushmore were spent according to regulations. Boland's job, and his personality, both irritated Borglum. When Borglum's first assistant, Major J. G. Tucker, a competent engineer who had worked on Stone Mountain, sided with Boland on the issue of where to get electric power, Borglum questioned his loyalty; when Tucker couldn't get paid his promised salary, he resigned. For the record, Borglum demanded Tucker's resignation.

While serving on the commission, Boland came to Borglum's desperate aid more than once. He guaranteed bank loans Borglum needed to keep his home, and he would press the commission to give from their own pockets when money was in short supply. He even gave Borglum a personal loan.

Nevertheless, Borglum resented the need to clear any of his plans with the Mount Rushmore Commission — and determined to rid himself of them. By 1938, three of the sculpted heads had been dedicated and Theodore Roosevelt's likeness was well under way. Rushmore was becoming a source of national pride and Congress was more inclined to fund the monument. In this atmosphere, Borglum's contract had expired and he was insisting on changes before he signed a new one. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes was curious about Borglum's inability to work with Boland and the National Park Service (which oversaw the Rushmore Commission), and set to investigating the matter. He was informed in a report that Boland was "an excellent man personally, a useful citizen, a successful businessman, and a loyal supporter of Rushmore" and that work under the National Park Service was more efficient than it had been previously.

Meanwhile, Borglum's allies introduced a new appropriations bill for the monument that would call for a new commission — one that Borglum would sit on and control. Borglum was the star witness before the congressional committee considering the bill. Boland was invited to attend but declined, fearing that if he were to testify to Borglum's inconsistencies and personal extravagances, Rushmore's future would be threatened. After news reports suggested that Boland was not a good manager, he wrote a statement that was introduced to the committee. The statement concluded:

"Mr. Borglum is an artist and I am a businessman. Therefore it is only natural that we should at times disagree regarding the business functions of the Commission. Such differences, however, have never been serious and an amicable understanding has always been reached.

"My only desire is to have the Mount Rushmore project completed in the best possible manner, and to have Mr. Borglum carry on his great work, with the able assistance of his son, Lincoln, the continued cooperation of the Commission, and the efficient supervision of the National Park Service."

As things came to a head, Boland revealed where his true loyalties resided -- with the monument. He agreed to resign his place on the old commission if the appropriations bill could be passed for the completion of Mount Rushmore. He did, and it did.

The very next year, 1939, the government reorganized its entire budget to better deal with the continued Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe. Rushmore was again to be supervised by Boland and the National Park Service. Borglum was not the only one who was upset. Harold Ickes commented, "Mr. Borglum has customarily made it so unpleasant ... that I groaned all night following the day when I learned that the Mount Rushmore National Memorial Commission had been sent here for administration."

After all this, Borglum and Boland made up. The reconciliation was engineered by their wives, it seems; soon the Borglums were over at the Bolands' for dinner again, and the Bolands were socializing at the Borglum ranch. Boland passed the next several decades in relative obscurity until his death in October, 1958. As much as Mount Rushmore required the hand of Gutzon Borglum for its creation, the monument needed John Boland to guide the project's finances through the hardships of the Depression.