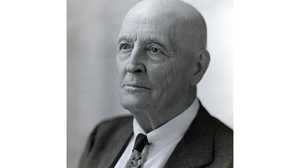

Gutzon Borglum

John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum liked to tinker with his own legend, subtracting a few years from his age, changing the story of his parentage. The best archival research has revealed that he was born in 1867 to one of the wives of a Danish Mormon bigamist. When his father decided to conform to societal norms that were pressing westward with the pioneers, he abandoned Gutzon's mother, and remained married to his first wife, her sister.

In 1884, when Gutzon was 16, the family moved to Los Angeles. His father, unhappy in California, soon returned to Nebraska, but Gutzon stayed behind. He studied art and met Elizabeth Jaynes Putnam, a painter and divorcee 18 years his senior. Lisa Putnam became a teacher and mentor to Gutzon, helping manage his career and advising his education. They were married in 1889. While in California, Gutzon painted a portrait of General John C. Fremont and learned the value of having a wealthy and socially connected patron. Although the general died a few years after sitting for his painting, his widow provided Borglum with contacts to men such as Leland Stanford and Theodore Roosevelt.

The Borglums traveled to Paris to work and study, and there Gutzon met sculptor Auguste Rodin. As much as he admired Rodin, more than one historian has suggested that the reason Gutzon gave up painting was to compete with his brother Solon, who had been making his name as a sculptor. Gutzon's talent was immediately apparent and he found a few commissions (certainly the fact that Solon had already associated the name Borglum with fine sculpture didn't hurt). At the same time, Gutzon's marriage was falling apart. He left Paris alone in 1901 and aboard ship met mary Montgomery, an American who had just completed her doctorate at the University of Berlin. He and Mary wed as soon as Lisa granted him a divorce. They bought a house and farm in Connecticut and named it "Borgland."

Borglum's major work back in America included a bust of Abraham Lincoln, which he was able to exhibit in Theodore Roosevelt's White House. The Lincoln portrait and other much admired works gave Borglum a national reputation, and he was invited by Helen Plane of the United Daughters of the Confederacy to carve a bust of Robert E. Lee on Stone Montain in Georgia. Borglum's conception was bigger than Plane's and Stone Mountain became his first mountain carving project, and where Borglum developed some of the techniques that would later be used on Rushmore.

While at Stone Mountain, Borglum became associated with the newly reborn Ku Klux Klan. Whether this accorded with a racist world view, or if it was simply one way to bond with some of his patrons on the Stone Mountain project, is unclear. Frankly, Borglum had little time for anyone, white or black, who was not a Congressman or millionaire, or happened to be in his way. There is no indication, for example, that he treated his long-suffering black chauffeur Charlie Johnson any differently than any white employee — he owed him back pay just like everyone else. Stone Mountain was not finished by Borglum, but it inspired his next job: Mount Rushmore.

When South Dakota state historian Doane Robinson read about Stone Mountain, he invited Borglum out to the Black Hills of South Dakota to create a monument there. Borglum, perhaps realizing that Stone Mountain had only regional support, immediately suggested a national subject for Rushmore: Presidents george Washington and Abraham Lincoln. Theodore Roosevelt and Thomas Jefferson were added to the program soon afterward. Borglum had met and campaigned for Roosevelt, and by invoking that president's acquisition of the Panama Canal and Jefferson's Louisiana Purchase, the Rushmore monument became a story of the expansion of the United States, the embodiment of Manifest Destiny.

Work on the mountain was not constantly supervised by Borglum. When he was at Rushmore, Borglum would be climbing all over the mountain and all over the hills, to determine the best angle for each feature, and advising the carvers on how to create the nuanced details that might not even be visible from below. But after creating the models, siting the sculpture, and developing methods for transferring the image to the mountain and carving the rock, there were long periods during which Borglum's presence was not required. He would often leave his assistants, including his son Lincoln, to supervise the work and then travel. He would go to Washington, D.C. to lobby for more money, and he also traveled around the world, finding and completing other commissions, sculpting a Thomas Paine for Paris and a Woodrow wilson (for Poland, and meeting politicians and celebrities such as Helen Keller. (Helping her feel pieces by his old friend Rodin, he recalled her comment: "Meeting you is like a visit from the gods." He sometimes felt the same way about himself, writing in his journal: "I must see, think, feel and draw in Thor's dimension.") When he returned to the Dakotas, a rock might have been roughly blasted into an egg shape and he would be back to looking over every detail.

Borglum's stubborn insistence on having things done his way led to numerous confrontations with John Boland, who chaired the executive committee of the Mount Rushmore Commission. His temper and perfectionism caused him to fire his best workmen (who then had to be hired back by Borglum's son Lincoln). Borglum's ambition and hubris motivated him to recreate a landscape in his image (a tableau of prominent white men) rather than for the Native Americans who held the Black Hills sacred. Borglum was stubborn, insistent, temperamental, perfectionist, high-reaching, and proud — but these were also the characteristics that were required to carve a mountain. Big, brash, almost larger than life, only a man like Gutzon Borglum could have conceived of and created the monument on Mount Rushmore.

On March 6, 1941, Borglum died, following complications after surgery. His son finished another season at Rushmore, but left the monument largely in the state of completion it had reached under his father's direction.