The Keystone Boys

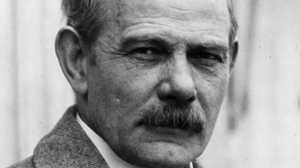

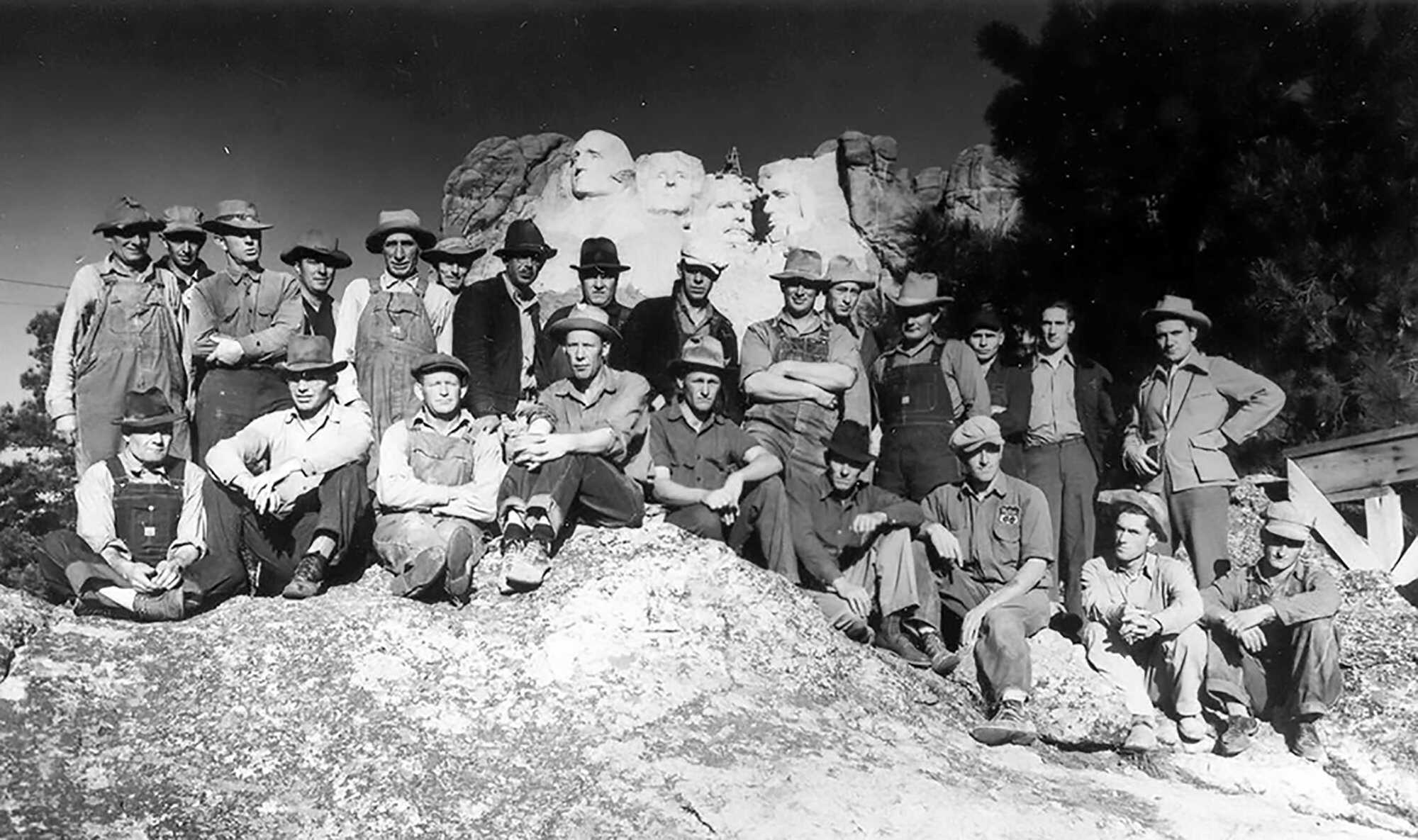

Gutzon Borglum complained a lot about the men who worked with him on Mount Rushmore, about how he wasn't given men who knew how to carve a mountain. Borglum's son Lincoln had artistic talent, as did Bill Tallman and Korczak Ziolkowski, two assistants to Borglum who came from back East. But where in South Dakota, Borglum wondered, do you find a whole crew of workmen who know how to carve a mountain into work of art?

Working on Rushmore meant finding the right point to carve on a cliff face, blasting stone with dynamite, working with jackhammers and chisels and other equipment that weighed half as much as you did -- all while your posterior was literally in a sling, hanging over the side of a mountain. The project required mechanics and powdermen, and men who understood rock, mostly miners. The workmen had colorful names: John Arthur "Whiskey Art" Johnson, Lloyd "Lively" Virtue, Jack "Palooka" Payne, Otto "Red" Anderson, Alton "Hoot" Leach, and the Peterson brothers, Merle and "Howdy" (Howard). These were tough men whose weekends were full of drinking (moonshine during Prohibition) and fighting — and playing baseball.

In fact, the Rushmore Memorial baseball team did pretty well against company teams from larger towns. In 1939, the year of Rushmore's largest budget, Merle Peterson helped Lincoln Borglum hire a bigger crew by recruiting good ballplayers. That year the Rushmore team represented the Black Hills in the State Championships, and made it to the semifinals.

Gutzon Borglum was proud of the baseball team, too, but he was an aloof and less approachable manager than his son Lincoln. Plus, he had a temper. Merle Peterson was fired eight times, which he thought was a record for the work crew. They couldn't compete, though, with Borglum's secretary Jean Peters, who lost track after her tenth firing, but thought the total was closer to 17. Still, Borglum had the respect of the men who worked with him. Red Anderson recalled his first meeting with Borglum: "He was working on the models of Rushmore, and the first thing that struck me was how lively the guy was. The models were maybe ten feet high and he had to work on 'em from a ladder. But when he came down off that ladder he didn't climb down — he jumped.

"He wasn't the sort of guy you'd 'howdy' and start talking to. You waited until he started talking to you...We had ups and downs, but we were always friends. He was a bear to get along with sometimes, and temperamental as the very devil, but underneath it all he was really a good man and a great man. I always respected him, and I think he always respected me."

One cold morning the crew was huddled in one of the mountaintop shacks warming up with some coffee when Borglum burst in the door. He thundered, "What the hell is going on around here?" When one of the laborers managed to say that they were just having some coffee, Borglum turned to his handyman and said "See to it that at about ten o'clock every morning we get some doughnuts and hot coffee up here for these bums!" According to local legend, that was how the coffee break was born.

The work on the mountain was hard, but the men had their fun. Their favorite hazing joke was to let out a little extra slack on the new guy's safety cable to drop him a few feet. There were accidents, too, but none fatal. The first big dynamite blast shot a boulder into the cable that brought supplies up the mountain. Years later, when the cable was adapted to carry men, a cable snapped and workers had to use the hand safety brake to lower themselves down again. Then one of the workmen pulled too hard on the brake chain and broke it. The car sped down the cable and a few men were thrown when it hit the base station. Amazingly, only one man was hospitalized, and he recovered completely.