North by Northwest

'Ah, Maggie, in the world of advertising, there's no such thing as a lie, there's only the expedient exaggeration. You ought to know that!" -- Cary Grant as Roger Thornhill, protagonist in Alfred Hitchcock's North by Northwest (1959).

The National Park Service would have done well to have reached the same conclusion before it dealt with Alfred Hitchcock, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and the world of movie-making! Plenty of "expedient exaggerations" surrounded the filming of scenes for Hitchcock's acclaimed thriller North by Northwest at Mount Rushmore in 1958. While the controversy the Mount Rushmore scenes caused appears humorous today, it was, at the time, a serious matter for the officials of the National Park Service and the Department of the Interior and for South Dakota's United States senator Karl E. Mundt. The reason for the controversy lay in one simple fact: master film director Alfred Hitchcock had long wanted to film a movie involving the "Shrine of Democracy," but the Park Service had concerns about the memorials potential "desecration." Like Gutzom Borglum, the artistic genius who had preceded him into the South Dakota wilderness and whose creation he longed to use as a backdrop, Hitchcock would not let the federal government or its minions stop him from achieving his dream.

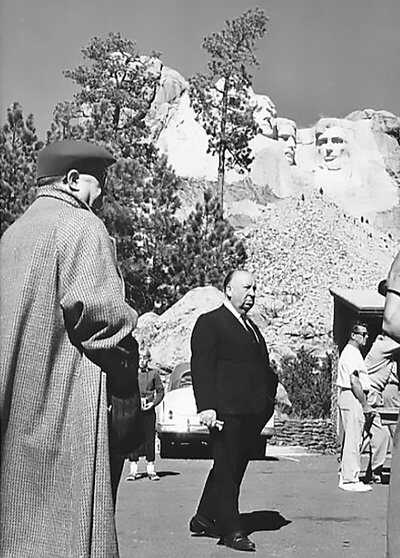

South Dakotans first learned of Hitchcock's intent to film at the site from a 15 May 1958 Associated Press report datelined Hollywood and printed in the Rapid City Daily Journal: "Alfred Hitchcock says he expects to realize his long ambition -- filming a chase over the Mount Rushmore Monument. He may be spoofing, but you never can tell with Hitchcock. After all, he has made use of the Statue of Liberty, and tilted liner Normandie, and other landmarks in his long and distinguished production of movie thrills." In the past the film maker has occasionally told colleagues about his dream to shoot at the memorial. "I've always wanted to do a chase sequence across the faces of Mount Rushmore," the master of suspense is reported to have said in 1957. Several years earlier, he had remarked, "I want to have one scene of a man hanging onto Lincoln's eyebrows. That's all the picture I have so far." During the summer of 1958, Hitchcock's Rushmore dream took form. From 28 July to 1 August, MGM location manager Charles Coleman visited Mount Rushmore, accompanied by Larry Owen of the Rapid City Chamber of Commerce. While there, Coleman talked with National Park Service officials about the idea of shooting scenes at the memorial.

To set the stage for the controversy that followed, it is important to understand the complicated plot of the movie, which one Hitchcock scholar has summarized as "a comic thriller about mistaken identity, political depravity, sexual blackmail, and ubiquitous role-playing." Even leading man Cary Grant complained to Hitchcock about the complexity, remarking, "We've already made a third of the picture and I still can't make head or tail of it." Grant plays Roger Thornhill, a New York City advertising executive abducted by Communist spies who have mistaken him for a fictitious CIA agent. Thornhill escapes, only to witness the murder of a United Nations official and be accused of committing the crime. The film chronicles his cross-country flight from both the police and the communist agents (James Mason, Martin Landau, and others), which takes him from New York to Chicago to Indiana and finally, to South Dakota. Along the way, Thornhill falls in love with the icy blonde CIA spy, Eve Kendall (Eva Maria Saint). The drama culminates at Mount Rushmore, with Kendall and Thornhill scrambling about the presidential faces to elude enemy agents.

While Hitchcock and screen writer Ernest Lehman conjured a complicated, but ultimately satisfying, spy thriller, they seasoned the movie with a few geographical liberties. In the finished film, a Frank Lloyd Wright-like house and the mythical "Cedar City," complete with an airport, perch at Mount Rushmore's summit. During the movie's climax, Thornhill, Kendall, and their pursuers simply drive or fly to the top of the "Shrine of Democracy" and then run willy-nilly about the four presidents' heads.

The issue of "chasing about" Mount Rushmore is critical to understanding both the movie and the resulting controversy. One simply does not chase about or even climb up Mount Rushmore without proper gear -- and permission from the National Park Service. In 1958, representatives for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) and the Park Service had signed an agreement concerning Hitchcock's filming at the memorial. In return for permission to use the site, the film makers promised that no scenes of violence would be filmed "near the sculpture [or] on the talus slopes below the structure." The agreement further prohibited the depiction of violence on "any simulation or mock-up of the sculpture or talus slope." The same restriction applied to all public-use areas of the memorial, real or simulated. The film makers, at least in their early correspondence, assured the government officials that the site would be "treated with the utmost respect. None of our characters would tread upon the faces or heads of the Sculpture," wrote Hitchcock's location manager.

Shortly before the shooting at Mount Rushmore was scheduled to begin, a reporter asked the director about the chase scene. Hitchcock, ever the showman, handed the journalist a napkin with the presidents' heads drawn on it and a dotted line purporting to show the chase path. The Rapid City newspaper printed the story and a picture of the napkin. Citing "patent desecration," the Department of the Interior (the Park Service's parent agency), summarily revoked Hitchcock's original permit and prohibited the filming of live actors in conjunction with either the real or mock-up faces. It later reissued a permit allowing the use of a Mount Rushmore mock-up on the condition that the presidents' faces be shown below the chin line in scenes involving live actors.

According to James Popovich, chief interpreter at Mount Rushmore National Memorial, Hitchcock was "terribly mad when we told him he couldn't shoot on the faces. He almost pulled the movie." Once he arrived in Rapid City on 15 September, however, Hitchcock became a model of citizenship and reassured South Dakotans of his good intentions. "It's a good thing for the world to see the big monuments that we have. This is part of America," the film maker expounded. "When they say we'll do something on Lincoln's nose, this is very bad. We wouldn't dream of it. In fact, it would defeat the purpose for which we are using Mount Rushmore in the film."

Shooting at Mount Rushmore, which had been scheduled to take two days, took place on 16 September 1958. According to the local press, the "beautiful" weather and the "cooperativeness" of Black Hills residents impressed both MGM officials and Hitchcock. In his log for the day, the memorial superintendent stated that the crew had been "well organized and in spite of the crowds, equipment, and extras on hand, everything went smoothly and the shooting was finished a day ahead of schedule." While the monthly report of the chief ranger echoed the superintendent's opinion, it also shadowed more conflict to come. "This production did not pose any difficulty protection-wise. The movie company was very cooperative," stated the official. "However, considerable adverse publicity did bring in several complaints. MGM at this writing is making several still shots of the sculptures. Permission was granted for these still shots only after receiving verbal confirmation from the Regional Office."

Altogether, the crew lensed three scenes at Mount Rushmore: Eva Marie Saint's staged shooting of Grant in the memorial's cafeteria, the parking lot scene in which the rangers haul away Grant's "dead" body in a station wagon, and a number of views of the memorial from various terraces. Ironically, the way in which some of these general views and the still shots of the stone faces were used contributed to much of the subsequent controversy surrounding the film. Technically, Hitchcock would keep half of his word to the National Park Service. While he did not film any chase scenes on the real memorial, he eventually shot them on a studio mock-up or against a background composed of the still shots. At the close of the on-site filming in September of 1958, the Rapid City Daily Journal innocently reported, "A replica of the national memorial will be reproduced full scale at Culver City for additional close up scenes." "Closeup scenes" was just an "expedient exaggeration" meaning the climactic death struggle between "good guys" Grant and Saint and "bad guys" Mason and Landau. The National Park Service and the Department of the Interior would object to the use of these scenes in the finished film, claiming their violence desecrated the national memorial.

Nearly a year after filming at Mount Rushmore ended, press reports confirmed that the Park Service's early suspicions about Hitchcock's sincerity regarding the agreement were about to be borne out. The press was reacting enthusiastically to the use of Mount Rushmore as a locale in the soon-to-be-released film, and the director appeared happy to foster yet another "expedient exaggeration" — the illusion that the movie's climax occurred on the real Mount Rushmore. Critic Alice Hughes of Hollywood Variety called the Black Hills location "probably the boldest terrain ever chosen on which to bring about the exhilarating, murderous finale. One shouldn't reveal the amazing locale, but the temptation is too great. Six presidents' [sic] heads and faces carved out of the stony peaks of Mount Rushmore, South Dakota, by sculptor Gutzon Borglum, provide a breathtaking background where the hero and heroine and the two foreign villains grapple for life." Hughes mistakenly reported, "This is no studio mock-up; the actual national monument serves as the scene in those last terrifying moments of sliding down the neck and chest of George Washington and the craggy features of Abraham Lincoln."

Louella Parsons of the Los Angeles Examiner gushed: " I like James Mason when he is being ornery. That suave British voice can be so deadly when he's a villain. Alfred Hitchcock must agree because it is Mason who will terrorize and chase Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint all over the granite presidential faces on Mount Rushmore." In what must have been the last straw for National Park Service officials, she concluded, "Wouldn't you know Alfred Hitchcock gets Cary Grant to commit a movie murder in North by Northwest by having him push [an enemy agent] off Lincoln's nose."

Hoodwinked by Hitchcock and MGM, government officials decided to fight back, although the effort proved to be too little, too late. On 28 July 1959, acting interior secretary Elmer F. Bennett wrote a heated letter to MGM president Joseph E. Vogel: "In accepting these terms [no scenes of violence on the memorial or mock-up], MGM promised to adhere to them. Then MGM, without notifying the other party to the agreement, proceeded to fake scenes which expressly violate the studio's pact. The phony studio shots leave the average customer with the idea that the scenes of violence were staged on the memorial itself."

With the press spreading enthusiastic but erroneous rumors, the Park Service and the Interior Department conceded that little could be done to correct the misconception. Bennett therefore asked Vogel to remove from the movie the credit stating: "We gratefully acknowledge the cooperation of the United State[s] Department of the Interior and the National Park Service in the actual filming of the scenes at Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota." According to Bennett, moviegoers would "doubtless receive the wrong impression that the Department and Park Service cooperated in filming the scenes of violence at the end of the film." Bennett then warned Vogel, "Future permit applications in the National Park Service areas will receive closer scrutiny than heretofore." In 1957, the Park Service had rejected the request of another film maker to stage a similar "game of cops and robbers" at Mount Rushmore.

Though beaten by Hitchcock and MGM in this instance, the Interior Department attempted to change the film industry code of ethics and this prevent "similar violations in the future." In a letter to Eric Johnston, president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), Bennett suggested that the MPAA "consider the appropriateness" of a clause concerning filming in national parks. While he reiterated his warning that "the experience gained in this instance will lead in the future to closer restrictions in such permits," Bennett closed on a conciliatory note, offering to cooperate in the writing of such a clause.

Kenneth Clark, MPAA vice-president, responded to Bennett's letter with a healthy dose of Hollywood pseudo-charm: "There must have been an unfortunate misunderstanding because I am confident that Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer would always live up to any agreement that is made. It is regretful that such a misunderstanding has developed and I want to express hope that it will not in any way impair the fine relationships that have always existed between your Department and the motion picture companies belonging to our Association." Clark went on to pooh-pooh the idea of placing a clause in the industry's code concerning filming in national parks. "The Production Code is concerned with the moral content of the films [and] would not be appropriate" for dealing with concerns of the Park Service. He continued, "I know it does not take such a clause in the Code to assure you of the continued harmonious cooperation of our member companies. You can be sure too that this is the attitude of our Association." Completely sweeping the matter under the cinematic rug, Clark concluded, "Let us know when any of us here can be helpful to the Department."

In the eyes of the film industry, Clark's reply may have been the end of the matter. However, to the Park Service and the Interior Department, it was not quite the last take. The "Feds" had a secret weapon -- South Dakota's senior United States senator, Karl E. Mundt. A member of the powerful foreign relations and appropriations committees, Mundt got things done for South Dakota. Perhaps he could make the film makers see the government's point, as he had done in a similar situation in 1939.

Two months into his first term as a United States representative, Mundt had attended an Izaak Walton League meeting in Silver Spring, Maryland, where he viewed the government-produced documentary The Plow that Broke the Plains. The film depicted the causes, some accurate and some inaccurate, of the Dust Bowl in the nation's heartland. Angered by its depiction of the Dakotas as "a country of high winds and sun, without rivers, without streams, with little rain," Mundt used his first speech on the house floor to rail against the film. He also worked with a number of organizations within South Dakota to get the film pulled from distribution, even though ten million viewers had already watched it over the last two years. Nonetheless, Mundt was proud of having put a halt to this bad publicity for the state and referred to this success in his 1940 campaign. Thus, twenty years later, the senator was again willing to oppose a motion picture that portrayed his home state in what he thought was an unfavorable light.

On 13 August 1959, Park Service director Conrad L. Wirth sent Mundt copies of the ongoing correspondence concerning the Hitchcock film. By this time, former Rushmore superintendent Charles Humberger and current chief ranger Leon Evans had reviewed the movie at the Elks Theater in Rapid City. They, too, objected to the chase scenes and agreed with their superiors that "the terms of the application for filming the production were not adhered to." Wirth related this information to Mundt, stating, "It is an act of deliberate desecration of a great National Memorial to even imply that a game of cops and robbers, for the sole purpose of producing movie thrills, has been played over the sculptured faces of our most honored Presidents." Wirth, who had also written to Sen. Francis Case, Rep. George McGovern, and Rep. E. Y. Berry, informed Mundt that he was supplying the senator with the information " in case the controversy is brought to your attention by some other source." Mundt reacted quickly and vehemently. Two days later, he responded to Wirth, "As you may well imagine I have received a great number of complaints concerning the motion picture North by Northwest and the acts of desecration simulated in that picture." The senator vowed to take dramatic action just as he had done twenty years earlier with The Plow That Broke the Plains. "I agree that the Department should make every possible effort to have the picture recalled and corrected," he told the Park Service director," and if that is not done I think the Department should seriously consider the whole procedure by which they permit future picture applications in the National Park Service area." In a postscript, Mundt told Wirth that he planted to submit the Park Service correspondence for the Congressional Record early the next week "so that the general public will know accurately the attitude of the Department of the Interior and the National Park Service." He concluded, "I shall probably include it in a talk on the Senate floor on Monday afternoon, August 17." Wirth responded to Mundt on 20 August with a four-page letter and more extracts of letters, reviews, and news stories about North by Northwest. The Park Service director recommended that if Mundt decided to speak in the Senate about the Park Service's problems with the movie, he "should make a very firm statement to the effect that the desecration was the result of a studio mock-up" and not the use of the actual memorial. Wirth ended his letter with an important bit of information. "I have been informed by a local representative of the Company," he wrote, "that the credit line to which the Secretary objected has now been removed from this picture." This statement apparently cooled the senator's ardor over the affair. The next week, Mundt wrote to thank Wirth for the information, adding, "I particularly appreciate having the material made available to me and it is possible that at some other time I will prepare a speech and put it into the Record for you."

The senator may have realized that by August 1959 it was too late for anyone to do much of anything about the movie -- except buy tickets and see it. MGM had released North by Northwest in New York on 6 August to favorable reviews. A. H. Weller, writing for the New York Times, called the movie "a suspenseful and delightful Cook's Tour of some of the more photogenic spots in these United States." He found the Mount Rushmore climax "a bit overdrawn," however.

After all the intrigue -- both on screen and off -- what is the legacy of the filming of North by Northwestat Mount Rushmore? The most obvious legacy is the movie itself. Hitchcock directed a great film that exploits a great location. His biographer, Donald Spoto, notes that the director had "a special fascination in planning and filming the most outrageous human deed in unforgettable and visually arresting ways, the better to impress his audience with the almost chimerical nature of the act of murder." Neil Sinyard, another Hitchcock scholar, adds that the director's depiction of bizarre acts committed against benign backgrounds reached its height in North by Northwest, a film in which "a hotel lobby is the setting for kidnapping, the United Nations building for murder, and the stone face of Mount Rushmore for perilous pursuit." A recent reviewer calls North by Northwest "possibly Hitchcock's most likable film if only because it is an over-size bag of his best old tricks."

Part of Hitchcock's success as a director was due to his "obsession with order and controlling every last detail of his film," traits he carried to legendary lengths. This attention to detail, coupled with his long-held desire to film at Mount Rushmore, combine to make the climax of North by Northwest one of the greatest episodes in his long and illustrious film career. Spoto notes, "The last minutes of the film comprise one of the most famous set pieces in Hitchcock's career -- the realization of a longtime desire. He had at last celebrated the giant impassive faces." Thus, despite his protestations to the contrary, it appears that the director probably had no intention of obeying any portion of the Park Service agreement that stood in the way of his goal.

A second legacy of North by Northwest is the greater renown the film brought to the memorial. The passage of time and the film's achievement of "classic" status have disproved the fears of government officials. Aside from preventing Hitchcock from doing any shooting at Mount Rushmore, the Park Service could probably have done little more to prevent what some considered at the time its "desecration." While park rangers were able to keep an eye on Hitchcock at Mount Rushmore, they had no control over him on a Hollywood back lot. Theirs was a lost cause from the beginning. By the time Interior Department brass enlisted Senator Mundt's aid, the film was ready for distribution. The controversy only served to fan the hype -- and the ticket sales -- for the film.

Gutzon Borglum the sculptor may have winced at seeing Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint climbing over even a mock-up of his "Shrine of Democracy." However, Borglum the showman probably would have smiled. "It's just my opinion," said Nicole Swigart, a seasonal interpreter at Mount Rushmore, "but Borglum probably would have liked how the Memorial was shown in North by Northwest. He liked publicity." The sculptor may even have sympathized with Hitchcock in his dilemma, for Borglum experienced similar frustrations with government officials in carving Mount Rushmore. Further, as an avid moviegoer who sometimes saw the same film three or four times, Borglum could have appreciated Hitchcock's artistic abilities.

According to chief interpreter Popovich, "In the years following the movie, Mount Rushmore park rangers removed more visitors from the secured areas than in any previous years." Today, the movie continues to draw visitors to the memorial. "Even after all these years," Swigart said, "there's still publicity from the film, It still brings people in with questions." Just minutes after she made this comment, a tourist entered the sculptor's studio at the memorial. Almost as if on cue, the older gentleman asked, "Was North by Northwest filmed here?" Thirty-five years have elapsed since Hitchcock worked his "expedient exaggerations" with Mount Rushmore. Yet, this simple question from a tourist is probably the most fitting tribute to North by Northwest and its lasting impact on South Dakota's "Shrine of Democracy."

Alfred Hitchcock's "Expedient Exaggerations" and the Filming of North by Northwest at Mount Rushmore

by Todd David Epp, originally published in South Dakota History, vol.23, no. 3, fall 1993, pp. 181-196. Reprinted with the kind permission of the South Dakota State Historical Society.