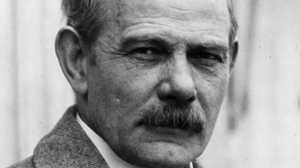

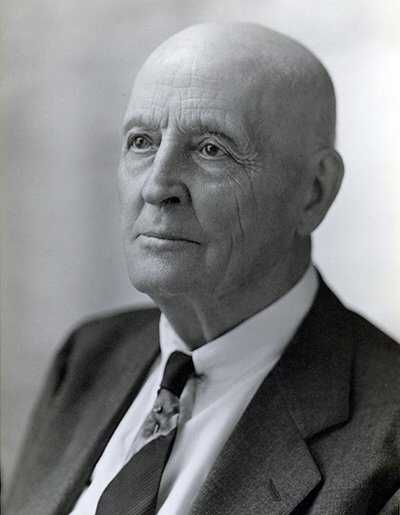

Doane Robinson

Sadie Robinson became an older sister in 1856 but could not pronounce her baby brother's first name. So she called Jonah LeRoy Robinson "Doane," and his family name stuck.When he came of age, Doane Robinson started working as a farmer in Minnesota, but found he was more interested in books than crops. He became a lawyer and set up a practice in the Dakotas. A second career change found him studying history, and eventually securing a job as South Dakota's state historian. In that position he wrote histories of the state, biographies of important personages, and collected and archived thousands of artifacts and articles for the state historical society.

Robinson was encouraged by the tourism dollars the Black Hills brought, but thought, "Tourists soon get fed up on scenery unless it has something of special interest connected with it to make it impressive." Reading about Stone Mountain, Robinson had the idea to propose sculpting the Needles, giant pillars of granite, into the forms of some of the West's greatest heroes, both Native Americans and pioneers. In 1923 he wrote to a man considered one of America's best sculptors, Lorado Taft. Taft was ill, however, so the next year Robinson made a similar proposal to Gutzon Borglum. It was a good time to offer work to the artist — he and his patrons at Stone Mountain, Georgia were in an intractable dispute. Borglum agreed to the project but suggested that the subjects be George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, making the project a national, rather than regional, monument.

Robinson introduced a bill into the state legislature to authorize carving a mountain in Custer State Park and asking for funds to begin surveying the site. The funds were refused, but permission was granted. The monument was not unanimously welcomed. Native Americans saw the carving as an abomination, and local newspapers published hostile comments. Cora Johnson, an early environmentalist, wrote attacks in the Hot Springs Star against what she viewed as a desecration of the landscape. Borglum refused to refer to her by name, only as "that Hot Springs person" and "an agent of evil."

Robinson met Borglum on the artist's first visit to South Dakota in 1924. On his second visit in 1925, the sculptor announced that he would not carve the Needles, but would find an appropriate mountain instead. After Borglum decided on Rushmore, Robinson, then 69 years old, joined a party in scaling the mountain.

From that moment, Robinson became the de facto local manager of the project and he scrambled, along with Senator Peter Norbeck, to facilitate and appease the efforts and demands of the rather headstrong artist. When Borglum decided to hold a dedicatory spectacle, he wired: "SHALL BRING SOME COSTUMES FOR CEREMONIES CAN YOU GET A FEW REAL INDIANS FOR SPECTATORS ... "

The man was hard to keep track of, and Robinson sent this message on the day he was expected: "BORGLUM DID NOT ARRIVE ... DO YOU KNOW HIS PLANS ... SPECTATORS AND INDIANS HARD TO HOLD."

When the day did come, Robinson's was one of the speeches for the occasion. "Americans!" he declaimed. "Stand uncovered in humility and reverence, before the majesty of this mighty mountain!"

The biggest problem with working with Borglum was always money. "I really do not know what financial support is back of the proposition," Robinson wrote to Norbeck. Robinson had been repeating Borglum's assurance that South Dakotans would not shoulder the brunt of the financing, and when the artist then asked the locals for their contributions, Robinson felt like he looked like a fool or a liar. Somehow, Robinson managed to function despite Borglum's constant boasts and contradictions.

When work began, the headquarters of the project were established south of Rushmore itself on a pine-covered hill. In honor of Robinson, this spot is known as Doane Mountain.

In 1929, in the last days of Calvin Coolidge's term, the president signed a bill giving appropriations to Rushmore and creating a commission to oversee the project. The Mount Rushmore National Memorial Commission consisted of a dozen important men -- but not Doane Robinson. He was neither rich, nor had he the large-scale managerial experience the project needed. Still, Rushmore had been his idea in the first place, and he was heartbroken. "South Dakota has already forgotten that I ever had anything to do with the matter." He was disappointed that his friend Norbeck hadn't stood up for him, but in fact, Norbeck had refused a position on the committee in solidarity with his friend. Later in the year, a Mount Rushmore National Memorial Society was formed to solicit $100 memberships and Robinson was put in charge of that effort, but generally, his labors were no longer enlisted.

After retiring as state historian, Robinson became "a farmer with the grime of toil on my fists." He lived long enough to see the completion of Rushmore, and died in 1946.