The creation of Mount Rushmore is a story of struggle — and to some, desecration. The Black Hills are sacred to the Lakota Sioux, the original occupants of the area when white settlers arrived. For some, the four presidents carved in the hill are not without negative symbolism. The Sioux have never had much luck dealing with white men.

In the Treaty of 1868, the U.S. government promised the Sioux territory that included the Black Hills in perpetuity. Perpetuity lasted only until gold was found in the mountains and prospectors migrated there in the 1870s. The federal government then forced the Sioux to relinquish the Black Hills portion of their reservation.

These events fit the pattern of the late 19th century, a time of nearly constant conflict between the American government and Plains Indians. At his second presidential inauguration in 1873, Ulysses S. Grant reflected the attitudes of many whites when he said he favored a humane course to bring Native Americans "under the benign influences of education and civilization. It is either this or war of extermination." Many of the land's original occupants did not choose to assimilate; for them war, was the only option.

In South Dakota, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse led various Sioux tribes against the U.S. Army. They had a notable success against General George Armstrong Custer and his troops, but the army's defeat at the Battle of Little Bighorn in America's centennial year, 1876, would cause the federal government to redouble its efforts. (Some of the area in which Rushmore stands was eventually purchased by the state of South Dakota and developed as Custer State Park; the rest was part of the Black Hills National Forest.) South Dakota was also the site of the last major defeat of Native Americans at the Battle of Wounded Knee in 1890.

In his bestselling 1970 history of Native Americans' experiences in the West, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Dee Brown explains that the "battle" was actually a massacre where hundreds of unarmed Sioux women, children, and men were shot and killed by U.S. troops. The history of Wounded Knee would spur American Indian Movement (A.I.M.) activists to occupy the site in 1973. They demanded the federal government honor the treaties made with various tribes. The FBI became involved in what became known as the Second Siege at Wounded Knee, and a tense standoff resulted in the death of two Native Americans and injury to others on both sides. Violence continued to erupt for several years, including a June 26, 1975 firefight on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota that ended with the death of two FBI agents and one Native American. In a case that continues to spur controversy, A.I.M. member Leonard Peltier was convicted of killing the FBI agents, and sentenced to two consecutive life sentences in prison.

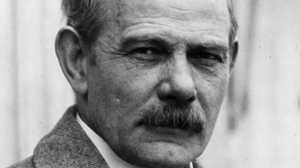

In 1927, with a history of turmoil as a background, a white man living in Connecticut came into the Black Hills and dynamited and drilled the faces of four white men onto Mount Rushmore. At the outset of the project, Gutzon Borglum had persuaded South Dakota state historian Doane Robinson the presidents would give the work national significance, rejecting Robinson's initial suggestion that the sculpture honor the West's greatest heroes, both Native Americans and pioneers.

The insult of Rushmore to some Sioux is at least three-fold:

1. It was built on land the government took from them.

2. The Black Hills in particular are considered sacred ground.

3.The monument celebrates the European settlers who killed so many Native Americans and appropriated their land.

To counter the white faces of Rushmore, in 1939 Sioux Chief Henry Standing Bear invited sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski, who worked briefly at Rushmore, to carve a memorial to the Sioux nation in the Black Hills. Perhaps wary of Borglum's troubles with financial administrators, Ziolkowski personally bought a mountain top with a granite ridge and financed the entire project privately. The statue, envisioned as a freestanding sculpture of the great Sioux chief Crazy Horse, will be much larger than any of the Rushmore figures. Korczak Ziolkowski died in 1982, but his family continues to work on this awesome undertaking; Crazy Horse's face was completed and dedicated in 1998. Although the subject of this work addresses one aspect of Rushmore's offenses, the land is still considered Sioux property, and the mountain that the Ziolkowskis are carving is still sacred. The Crazy Horse monument is not without its own dissenters and critics.