When a Game Is More Than Just a Game

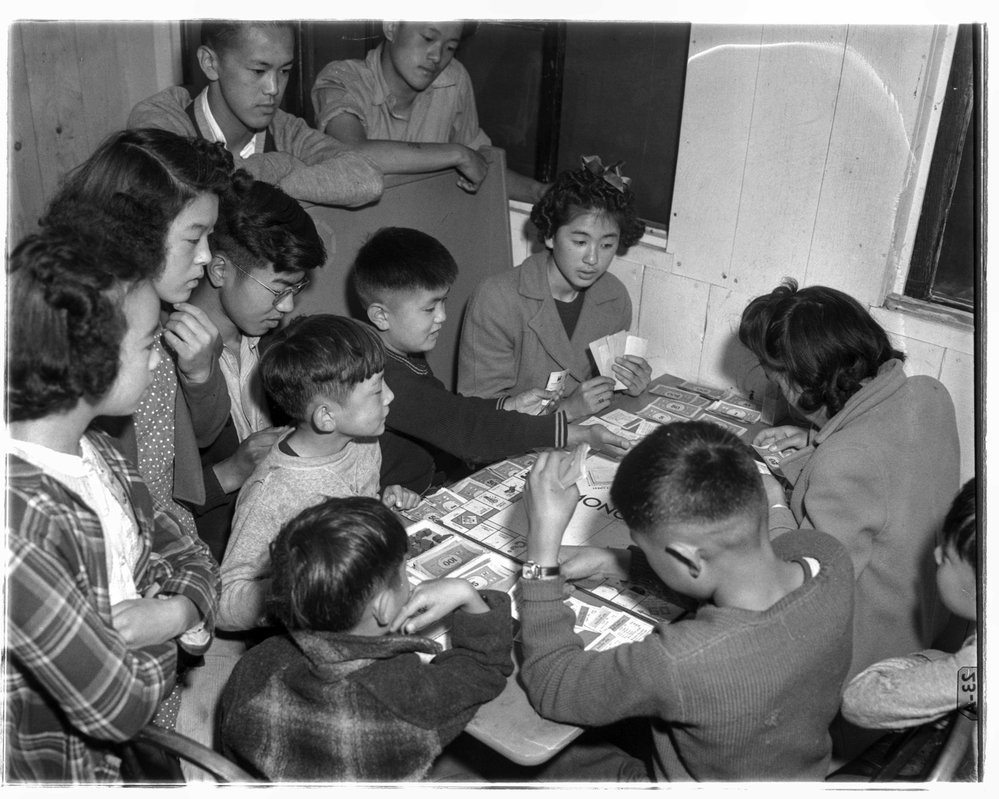

There's far more to this photograph of Japanese American children playing Monopoly than meets the eye.

This article is the third in a series called A Thousand Words, where we feature an interesting image from one of our films alongside an essay about why that picture is worth, well, a thousand words.

In June 1942, a staff photographer for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer filed a photo at the newspaper’s offices of a group of children playing the board game Monopoly. Handwritten on the sleeve containing the photo negative is its location—Puyallup, Washington. It is the other identifiers on the envelope, though, that begin to explain what differentiates the image from other, similar snapshots of kids playing popular board games: “Japanese colony, Camp Harmony,” the label also notes, words raising more questions than they resolve.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, six months before this photograph was taken, launched the United States into World War II. It also aroused deep distrust in the country of anyone of Japanese descent. Both foreign-born immigrants—known as issei within the Japanese community—and their American-born nisei children were targets of government suspicion. Two months after the attack, President Franklin Roosevelt, in his capacity as commander-in-chief of the American defense forces, signed Executive Order 9066, which designated vast areas of the country’s West Coast as military zones of exclusion. “Any or all persons” could be removed from military areas. E.O. 9066 set in motion the forced evacuation and detention of more than 110,000 people, two-thirds of whom were American citizens.

Starting in March 1942, Japanese Americans were first sent to “assembly centers” such as the euphemistically named Camp Harmony (a title bestowed by an army public relations officer). Hastily assembled in Puyallup in just 30 days, the detention facility was located on the site of the Washington State Fair. Seven thousand people were crammed into crude barracks; families were crowded into single rooms under leaky tar paper roofs with one cot. The walls between families’ rooms didn’t reach all the way to the ceiling, making privacy impossible. The camp’s inmates showered in communal facilities with a pipe running the length of the space that would spray water on everyone. Latrines had no partitions and consisted of two planks of wood with holes cut in them.

Nisei Masao Watanabe was 18 when he and his family were moved to the incarceration camp. “I had been to Puyallup a few times when it was the fairgrounds,” he told the Densho project for Japanese-American history, more than half a century later. “Little did I know that I would replace the pigs and the cows because they restructured the fairgrounds and the parking lots into these temporary hovels. They had a hell of a lot of nerve calling it ‘Camp Harmony.’ It was a real traumatic type of living.”

Cho Shimizu, who was five when his family was forced to abandon their farm east of Tacoma, was confused about what was happening. “It was hard for me to understand why we were leaving,” he recalled for the Seattle Times, 80 years after his incarceration in Puyallup. “Take only what you could carry. What about toys? When will we be back again? When will I see my friends again? My parents had no answers for me because they had no answers for themselves.”

The Puyallup detention center’s inhabitants had their own nickname for the accommodations, one that described the dullness of daily life: “Camp Harmonotony.” One survivor who was a teen when she was incarcerated, recalled, “there was this space between the barracks. When it was really hot everybody would go to one side of this lane and lean against the building and just sit there. And later on in the day when the sun changed its course, we'd go to the other side.”

At home back in Alaska, Arizona, California, Oregon and Washington, the detainees had had jobs and school. Torn from those things, they improvised new existences with what little they were given. Those who were teachers among the incarcerees held classes for the children. A “morale and recreation” officer was named and tasked with providing a program of activities.

Escapism and normalcy were in short supply, but games provided some of both. Shimizu recalled some sympathetic Puyallup residents throwing toys and sports equipment over the camp’s barbed wire fences for the children. Harry Kawahara, who was imprisoned at another assembly center in Tanforan, California, just outside San Francisco, remembered playing board games during his detention. “Monopoly was big,” he told Densho. “We had some card games too, but I remember most of our time was with Monopoly as far as board games were concerned.” The children in this photo, despite their exceptional circumstances, shared this activity with their fellow free citizens; there was a strong demand for Monopoly in the U.S. during the war years, as though impersonating aspiring magnates gave players a sense of control lacking during wartime. During the Puyallup camp inhabitants’ detention, other universal life milestones were observed as well: Army statisticians recorded a total of 37 births and 11 deaths.

Within months of their arrival, all of Puyallup’s inmates were eventually evacuated for “relocation centers”—permanent prison camps further inland—for the rest of the war. Most were taken by train to Minidoka, Idaho, where they remained for the next three years. In 1946, the Washington State Fair resumed at the fairgrounds, as Japanese Americans faced the challenge of creating new, post-war lives.

If you have ever played Monopoly, you can likely call to mind the “GO TO JAIL” square with its whistle-blowing police officer, at one corner of the game board. Landing on it means reporting directly to the tile lying cater-corner, depicting a prisoner behind bars. However, as the game’s rules state, “even though you are in Jail, you may buy and sell property, buy and sell houses and hotels and collect rents.” In real life, unless the Puyallup inmates had been able to place their belongings in the care of sympathetic and trustworthy neighbors, all of their property was forever lost.

Of course, games are different from real life. Still, for the time we play them we are transported somewhere else—perhaps an idealized America, where anyone can get rich, and anyone, with a roll of a die, can be free.

At American Experience we're always coming across photos from the past that we can't stop thinking about—images that are worth a thousand words.