Who Were the Scottsboro Boys?

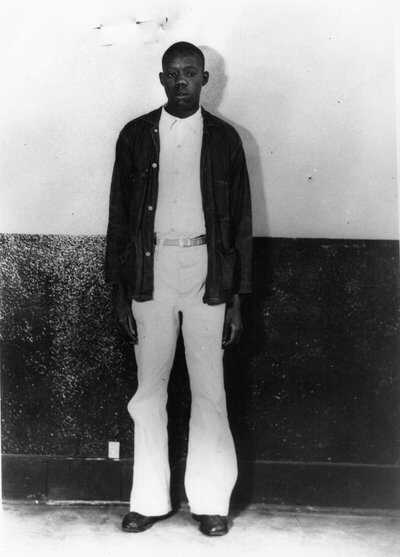

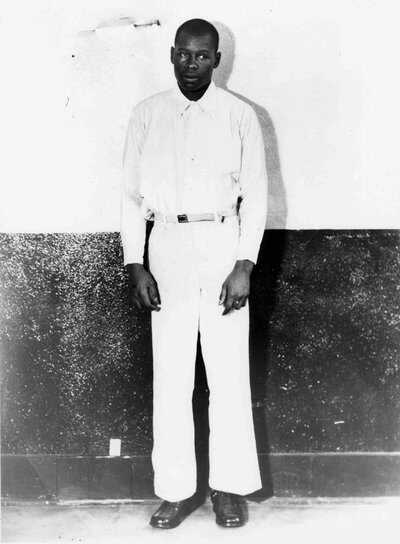

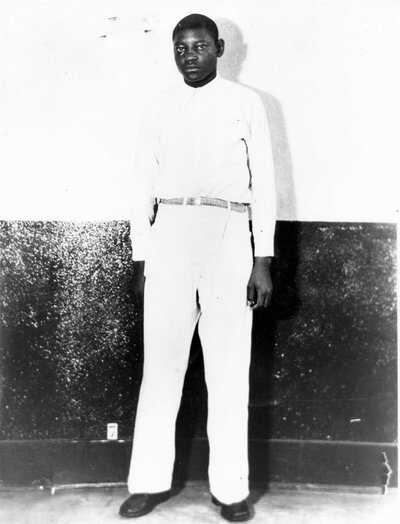

Olen Montgomery

"That thing they had here on May Day what good did it do. Not any at all. I'm still locked up in the cell. Instead of the I.L.D. trying to make it better for me here in jail they are making it harder for me by trying to demand the people to do things. Listen, send me some money. Send me three dollars like I told you in my first letter."

-- Letter to his mother after a May Day rally. May 3, 1934

Olen Montgomery was born in Monroe, Georgia. He made it through fifth grade and was the only defendant who could write at the time of the nine teenagers' arrest. Extremely myopic, and with a cataract in one eye, Montgomery could not see well at all. He was en route to Memphis, looking for work to buy some new eyeglasses, when he was taken from the train and arrested in 1931, at the age of 17. The pair of glasses he had was broken on the day of the arrest and he went for two years without a new pair.

He didn't know any of the other young men and boys with whom he was sentenced to death. However, being the most literate of the group, he wrote letters for the others. In a letter to their International Labor Defense lawyer George Chamlee, Montgomery wrote: "i Was on My Way to Memphis on a oil tank By My Self a lone and i was Not Worred With any one untell I Got to Paint Rock Alabama and they Just Made a Frame up on uS Boys Just Cause they Cud."

After the first trial, Montgomery was jailed for six years without a retrial. During that time, he wrote songs. In 1936 he wrote to Anna Damon of the I.L.D.: "You can get some small six string guitars and sent it rite away please I need it. if I live I am going to Be the Blues King. I want to surprise every Body some day Anna please don't wait a minute sent it rite on to me so I can Be practicing on these too songs that I have made up." His "Lonesome Jailhouse Blues" was published in the Labor Defender and began: "All last night I walked my cell and cried, Cause this old jailhouse done get so lonesome I can't be satisfied."

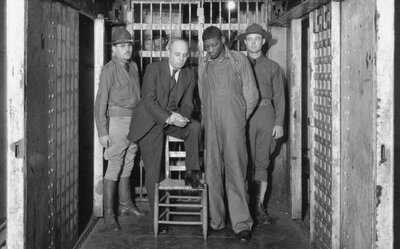

In a compromise in 1937, four of the defendants, including Montgomery, had the rape charges dropped against them. Defense attorney Samuel Leibowitz immediately picked them up from their jail, drove them out of the state, and put them on a train to New York.

In New York, Leibowitz had planned to place the boys in vocational schools, but offers from vaudeville proved too tempting. Thomas S. Harten, a minister, offered to manage the four released young men and presented them at Harlem's famous Apollo Theater. Harten's management style did not translate into good wages for the four, though. Leaving their manager, Montgomery and Roy Wright agreed to a national tour sponsored by the Scottsboro Defense Committee to raise money for their five incarcerated friends.

By 1938 Montgomery had bought himself a guitar and a saxophone and was taking music lessons. He continued to appear at meetings for the S.D.C. (which was paying his way until he could support himself with his music). Eventually the S.D.C. funds ran out and, after a brief stay in Georgia, Montgomery settled in Detroit, Michigan. There, after a night of drinking, he passed out on the bed of a girlfriend. Her landlady discovered them and accused him of rape, a charge that was dropped two days later.

After that, Montgomery spent his days in New York or Atlanta, usually drinking and occasionally receiving financial help from the NAACP.

Clarence Norris

"My name is Clarence Norris, one of the Scottsboro Boys. I was arrested in Alabama in 1931 and sentenced to the electric chair three times. The governor commuted my sentence to life in prison. I was released on parole twice, once in 1944, and I broke my parole and went back to prison until I got out in 1946. I broke my parole again and I have been free ever since. I want to know if Alabama still wants me." -- explaining the reason for his call to Alabama Governor George Wallace, 1973.

Clarence Norris was the son of a former slave. At the age of seven, he was put to work in the fields the family sharecropped, and went to school only minimally. After his father died, he began working for wages. When he was 19, he took a trip on the Southern Railroad to look for work; instead he was arrested with eight other African American teenagers he didn't know.

In jail, much of his time was spent on death row, and he was haunted by the executions he could hear from his cell, and began dreaming of his own death.

His first trial overturned, Norris was retried -- and again sentenced to death -- in 1933. His appeal went to the United States Supreme Court, and in Norris v. Alabama, the court decided that the absence of black jurors on the jury rolls of Alabama constituted a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection clause.

While awaiting a new trial, Norris wrote: "I am alone, out to myself. No one to say a Kind word to Me just listen to the other people away from me." In 1937, Norris was tried and convicted a third time. As a few of the others were released he suspected that "the State frame me out of the best of my life just to get those four boys free." The next year, his death sentence was commuted to life in prison by Alabama Governor Bibb Graves. While working in a prison mill, Norris lost a finger. Prison life was difficult, he was losing hope and, he despaired, "without hope, a man in prison is nothing."

In 1944 Norris was released on parole. After fleeing north, he was convinced to return to Alabama, in large measure to improve the lot of the two remaining Scottsboro defendants. Although promised leniency, Norris was returned to prison. Two years later, in 1946, Norris was paroled again.

After his release, Norris fled again, and assumed his brother's identity. He found work on his own, or with the help of friends like his defense lawyer, Samuel Leibowitz, and the NAACP. Two marriages quickly began and ended. He was arrested a few times, for gun possession, for gambling, and for stabbing a girlfriend. By the 1960s, he was living with a third wife and their children in Brooklyn, New York. Still in violation of his parole, he feared the effect of the revelation of his past on his children. The NAACP began proceedings to help determine if he was still a wanted man. Finally, in 1973, he called Alabama Governor George Wallace, and told one of the governor's subordinates the reason for his call. Did they still want him in Alabama? They did.

Enlisting the aid of NAACP lawyers, Norris requested a pardon. Alabama Parole and Pardon Board Chairman Norman Ussery required that Norris first turn himself in and reinstate parole before a pardon could be considered. The NAACP stepped up a public relations campaign and national newspapers, television networks and elected officials showed their support for Norris' position. The two other members of the Parole Board acted independently to void Norris' parole delinquency. This allowed Governor Wallace to approve a pardon.

On October 25, 1976, Clarence Norris, the last of the nine Scottsboro defendants, was no longer wanted by Alabama authorities. Moreover, he was officially declared "not guilty."

His comment on the pardon: "The lesson to black people, to my children, to everybody, is that you should always fight for your rights, even if it cost you your life. Stand up for your rights, even if it kills you. That's all that life consists of."

A speaking tour for the NAACP followed, and then a meeting with Wallace. Norris' autobiography was published in 1979. In the 1980s Norris was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, and he died on January 23, 1989.

Haywood Patterson

"I'd rather die than spend another day in jail for something I didn't do."

-- after getting 75 years, rather than the requested death sentence, January 24, 1936

Haywood Patterson was born in Elberton, Georgia in 1913. By the time he was fourteen, he was riding the rails, looking for work. He was 18 when he hopped on an Alabama-bound freight train with his friends Eugene Williams and Roy and Andy Wright. Patterson admitted that he was one of the black teenagers who fought with white hoboes, who had tried to force them off the train, but the charge against him was rape.

After the first trial, in which the nine Scottsboro defendants were tried in groups, Patterson became the point man in the subsequent trials. In March 1933 he was retried before Judge Jams Horton of the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, with Samuel Leibowitz as lead defense attorney. That trial ended in a conviction and death sentence, but Judge Horton set aside the conviction. The next trial, before Judge Williams Callahan, resulted in another death sentence.

A confusing series of filing deadlines was missed and Patterson lost his right to appeal. However, in their ruling on Norris v. Alabama, the United States Supreme Court recognized that the two cases were interrelated and strongly suggested that the lower courts look into the Patterson case again.

While in prison, Patterson found he regretted skipping out on school. "I held a pencil in my hand, but I couldn't tap the power that was in it." But he taught himself to read using a dictionary and a Bible.

Patterson was not particularly well liked, by the other Scottsboro defendants ( Clarence Norris swore he would kill Patterson if he had a chance), by other prisoners, or by the guards that ran the prisons. In Atmore Prison, he had to keep perpetually vigilant against physical and sexual assaults. To avoid the latter, Patterson himself became a sexual predator, and kept a "gal-boy." He lost faith in all things but one: "I had faith in my knife. It had saved me many times."

In February 1941, a guard paid one of Patterson's friends to kill him. This "friend" stabbed him twenty times, puncturing a lung and sending him to the brink of death. Amazingly, he recovered.

After alternating between being a maniacal terror and a model prisoner, Patterson managed to get himself transferred to Kilby Prison, and assigned to the prison farm. In 1948 Patterson made a successful prison break. Escaping to Detroit, he was eventually caught by the FBI, but the governor of Michigan refused to allow him to be extradited to Alabama.

Still in Detroit, Patterson worked with a journalist, Earl Conrad, to write his autobiography. Scottsboro Boy was published in June 1950. In December of that year, he was arrested after a fight in a bar resulted in a stabbing death. His first trial ended in a hung jury; the second was a mistrial. After his third trial, he was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to six to fifteen years. He served only one, as he died of cancer in jail on August 24, 1952.

Ozie Powell

"Momma ain't but one thing I want to tell you right now. Don't let Sam Leibowitz have anything else to do with my case."

-- after being shot, January 1936

Ozie Powell was born in rural Georgia, near Atlanta, in 1916. His parents separated when he was young and his mother worked for white people in Atlanta. He could write his name, but not much else.

When he was fourteen, he left home, working at camps and sawmills for weeks or months at a time before moving on. A year after leaving home, he was headed toward Memphis on a Southern Railroad train. At Haywood Patterson's first trial, Powell testified that he had followed a group of black boys who were going to throw the white boys off the train, but most of their opposition had jumped off the train by the time he got to the right car. Soon afterward, the train was stopped and Powell was arrested, along with eight other African American boys he didn't know.

He was tried before Judge A. E. Hawkins with Willie Roberson, Andy Wright, Eugene Williams, and Olen Montgomery. It was under Powell's name that an appeal went before the United States Supreme Court (Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932)), which ruled that the defendants did not receive adequate defense counsel.

At Haywood Patterson's third trial at the end of 1933, Ozie Powell's testimony was confused and contradictory. After a tough cross-examination, defense attorney Leibowitz asked him how much schooling he had had in his life. "About three months," was the answer. Patterson was convicted, but the decision was again overturned by the Supreme Court of the United States, this time on grounds that the absence of black jury members denied the defendants equal protection under the law, as required by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Patterson was tried and convicted again in January of 1936. Following the swift group conviction days after the incident, Ozie Powell had been imprisoned without a retrial for five years. While being transported from Patterson's trial back to the Birmingham Jail, he pulled out a pocketknife and slashed Deputy Edgar Blalock in the throat. Sheriff J. Street Sandlin stopped the car, pulled out his gun and shot Powell in the head. Blalock was out of the hospital the same day with ten stitches. Remarkably, Powell also survived.

His mother visited him in the hospital while Powell recovered. "I done give up," he told her. When asked why, he replied, "Cause I feel like everybody in Alabama is down on me and is mad with me." He suffered permanent brain damage from the shooting.

In January 1937 Dr. G. C. Branche examined the Scottsboro defendants and reported that Powell (like Roberson) had an IQ of about 64 and a mental age of nine. A 1937 Life magazine story on the defendants stated that Powell "can barely spell out words. Nobody writes to him."

In July of 1937 Powell pleaded guilty to assault and was sentenced to 20 years. Leibowitz requested that the six years already served be taken into account, but Judge Callahan, noting that the rape charge had been dropped against Powell, gave him the maximum sentence. He was sent to Atmore, the prison for dangerous criminals known as "the murderers' home."

In October of 1938 Powell was driven to the statehouse and an interview with Governor Bibb Graves. Graves decided against granting clemency.

Powell was paroled in 1946 and returned to live in Georgia.

Willie Robertson

"I just got to say I think I am doing well to keep the mind I got now. These people make wise cracks talking about somebody in Alabama to defend us, say I would get out better. They won't let the New York people come around."

-- to a visitor to jail, 1937

Willie Roberson was born on the Fourth of July, 1915, in Columbus, Georgia. His father walked out a month after his birth and his mother died when he was two. Willie was raised by his grandmother until her death in 1930. Although he made it through to seventh grade in Atlanta, a doctor later measured Roberson's IQ to be about 64, and his mental age at nine. He could not read or write and had difficulty speaking, and was the butt of many courtroom spectators' jokes.

Roberson had boarded the Southern Railroad headed to Memphis in search of free medical care for his syphilis and gonorrhea. He was in pain and lying in a car near the back of the train when he was arrested along with the 8 other African American teenagers accused of rape. The cane he used to walk with was thrown away on orders of the deputy that took him into custody.

This painful, syphilitic condition was evidence to defense attorney Samuel Leibowitz that Roberson could not have committed this crime. Judge James Horton agreed that it was unlikely that Roberson could have jumped from car to car as Victoria Price claimed. However, when it was revealed that Ruby Bates had been treated for syphilis herself, Roberson's venereal disease was cited as evidence of his guilt. Horribly, he was not treated for his condition until 1933.

Roberson was one of the defendants released in July of 1937, after six years without a retrial. Upon his release, Roberson said he wanted to become an airplane mechanic. After a brief foray into show business, Roberson settled into steady work in New York City. He was continually plagued by ill health, and suffered asthma attacks and bad luck. One night in Harlem, Roberson was in a bar when a fight broke out. Although not involved in the fight, he was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct. Of that incident he wrote, "I am again a victim of almost inconcievable maglinity and though I hartily dislike the role of myrter I have been cast in that role and it seems impossible to escape it."

Roberson's asthma had been greatly aggravated by his time in jail and he eventually died of an asthma attack.

Charles Weems

"Please tell all the young mens to try hard and not to go to prison for my sakes."

-- April 1944

Charles Weems was a native of Chattanooga, Tennessee. His mother died in 1915, when he was only four, and six of his seven siblings died soon afterwards. His father then fell ill and sent him to live with an aunt in Riverdale, Georgia. He was on his way home to Tennessee when he was pulled from the Southern Railroad train. He was twenty years old and did not know any of the other 8 African American defendants.

After the initial Scottsboro trial, Weems was not tried again until July of 1937. Fellow defendants Clarence Norris and Andy Wright had just lost their cases and defense attorney Samuel Leibowitz, in a frustrated summation of Weems' case, told the jury that he no longer believed he could convince a white jury of a black defendant's innocence in a rape case. "I'm sick and tired of this sanctimonious hypocrisy. It isn't Charley Weems on trial in this case, it's a Jew lawyer and New York State put on trial here." Whoever was on trial, it was Weems who was sentenced to seventy-five years in prison.

While in prison, Weems was tear gassed in his cell for reading International Labor Defense literature, and he asked his correspondents not to mention any labor actions in Birmingham, Alabama. In October 1937, after some of his fellow defendants were released, Weems was in the prison hospital for tuberculosis. In March of the next year, in a case of mistaken identity, he was stabbed with a knife by the prison mill foreman.

He was paroled in November 1943, and was offered a job in a laundry in Atlanta. He married and settled down into obscurity, keeping his job and his health, although his eyes would persist in bothering him from the tear gas a decade earlier.

Eugene Williams

"Sorry about my last letter -- hope it didn't make you angry. Didn't mean any harm whatever. only telling you how I felt towards you and what's more I could not help it."

-- Letter to the International Labor Defense apologizing for a frustrated outburst, December 1936

In 1931 Eugene Williams was traveling from Chattanooga to Memphis looking for work with his friends Haywood Patterson and Roy and Andy Wright.. At 13, he was one of the youngest of the nine African Americans taken from the train.

Williams was convicted in a speedy trial at Scottsboro with the other boys, but the Supreme Court of Alabama struck down his conviction based on his young age. He was still in jail without another trial in 1937 when the defendants received two visitors, a Life magazine reporter and Dr. G. C. Branche. Williams told Branche that he thought often of girls. Lifemagazine described him rather suspiciously as "a sullen, shifty mulatto" who "usually tries to impress visitors with his piety." In July of that year, he was released, along with three other defendants.

After his release and a brief entertainment career, Williams moved to St. Louis where he had relatives who helped him adjust to a relatively stable life.

Andrew Wright

"Mr. White, if you can't trust your mother, who can you trust?"

-- Andrew Wright to the NAACP executive secretary, August 1931

On March 25, 1931, Andy Wright left his native Chattanooga on a Southern Railroad freight train headed for Alabama, accompanied by his younger brother Roy and two friends, Haywood Patterson and Eugene Williams. All four of the African American teenagers were pulled off the train and arrested at Paint Rock, Alabama, after allegedly participating in a rape of two young women who were white. Andy was 19 at the time, and had had enough schooling that he could read and write a bit.

With the other teenagers arrested on the train, he was convicted in 1931. In the ensuing struggle between the NAACP and the International Labor Defense for control of the legal appeal, the I.L.D. acted swiftly in securing the trust and support of the defendants (who nevertheless vacillated) and their parents and legal guardians. It was the support of their parents that led most of the defendants to put their trust in the I.L.D.

In 1937 Andy Wright was sentenced to 99 years in jail for rape. He wrote a letter to the Scottsboro Defense Committee expressing concern that he and four of the other defendants had had their freedom traded for the four released that year. In Kilby Prison in Montgomery, Alabama, he was assaulted by both guards and prisoners, and spent time in the prison hospital. His continually poor health made it difficult for him to work in the prison industries and further antagonized his tormentors. Wright narrowly escaped an attack when Charley Weems took his shift at the prison mill and received knife wounds intended for Andy.

As bad as the physical punishment was, the psychic punishment may have been worse. By independent accounts, Wright was a good-natured prisoner, but he wrote: "A colored convict's very best behavior is not good enough for these officials here. Every time they open their mouths it is [']you black bastard.['] When we think we are doing right we be cursed at and kick around and beat like dogs."

In 1939 he wrote: "I am trying all that in my power to be brave but you understand a person can be brave for a certain length of time and then he is a coward down. That the way it is." When advised to "snap out" of his depressed state, he wrote: "What do you think I am a iron man[?] You all is out there w[h]ere you can do for yourself and get things done and then have a nerve to write and tell me to cheer up."

In November 1943, Wright received parole and was sent to work near Montgomery. The work the parole board had found seemed no better than prison to Andy, and he fled north. Allan Knight Chalmers, the chairman of the S.D.C., persuaded him to return south, in part so that Patterson and Powell's parole hearings might have more favorable results. When Wright returned, he was imprisoned despite promises of leniency.

In May 1950, Wright was paroled again, and Chalmers found a job for him in an Albany hospital. When asked about Victoria Price upon his release, Andy said: "I'm not mad because the girl lied about me. If she's still living, I feel sorry for her because I don't guess she sleeps much at night." He was the last Scottsboro defendant to leave jail.

In Albany the next year, Wright was accused of rape for a second time. A former girlfriend accused him of raping her thirteen-year-old foster daughter. Wright claimed he had merely bought a present for the girl and detectives hired by the NAACP confirmed his story. An all-white jury acquitted him after he spent another eight months in jail. His involvement in the Scottsboro case undoubtedly loaned credence to the woman's accusations. "Everywhere I go, it seems like Scottsboro is throwed up in my face. I don't believe I'll ever live it down," he lamented.

Andy Wright's run of bad luck continued: in subsequent years, he found little work in Albany, Cleveland or New York City. In a fight with his wife, he stabbed her; she didn't press charges, but he was forced to leave Albany for good and he settled in Connecticut.

Leroy "Roy" Wright

"They whipped me and it seemed like they was going to kill me. All the time they kept saying, "now will you tell?" and finally it seemed like I couldn't stand no more and I said yes. Then I went back into the courtroom and they put me up on the chair in front of the judge and began asking a lot of questions, and I said I had seen Charlie Weems and Clarence Norris with the white girls."

-- Roy Wright, to New York Times reporter Raymond Daniell, March 10, 1933

Roy Wright was born and raised in Chattanooga, Tennessee. When he was thirteen, he left home for the first time, to look for work with his older brother Andy, and their friends Haywood Patterson and Eugene Williams. He was arrested, along with eight other African American teenagers, on that trip. The youngest of the Scottsboro defendants, Roy Wright was interviewed by the New York Times while he awaited his trial in juvenile court.

At the initial trial, Roy testified that he had seen some of the other defendants rape the two girls, Victoria Price and Ruby Bates. Later, he claimed that that testimony had been coerced. His own trial ended in a hung jury, with 11 jurors seeking a death sentence and one voting for life imprisonment.

That was the only trial Roy had, and he spent the next six years in jail. He was in the car in transport to Birmingham Jail, and handcuffed to Ozie Powell when Powell slashed a deputy with a knife and was shot in return.

In January 1937, at the age of 19, he told a visitor, "If I have to spend more than one or two years longer, I just as well spend the rest of my life. If I was an old man perhaps I wouldn't mind it so much but that's what's against me; I'm young and innocent of the crime." He also complained: "I was put in solitary confinement in January 1936 and got fresh air once out of the thirteen months and that was last Friday. Some may count it a year but I count it thirteen months."

He liked to read, and kept a Bible with him always (he felt that pulp magazines with stories about others' pleasure would drive him crazy while he was in jail). Later that year, Lifemagazine described Roy as the "youngest and smartest of the Boys."

In July 1937 Roy was released with three of the other defendants. The quartet joined the vaudeville circuit, but were soon disillusioned with their fees. After breaking with their manager, Roy and Olen Montgomery went on a two and a half month tour organized by the Scottsboro Defense Committee, speaking in more than 40 cities to raise money and awareness for his brother Andy and the others still in jail.

After the tour, Roy found a sponsor in Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, the well-known African American entertainer, who offered to pay for Roy's education at a vocational school. After school, Wright served in the army, joined the merchant marine, and married.

In 1959, returning home from a tour at sea, Roy found his wife at the home of another man. In a fit of jealous rage, he killed her and then returned to his apartment, and his Bible, and shot himself.