Filming in Scottsboro

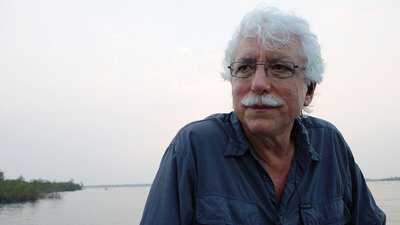

Cinematographer, Tom Hurwitz talks about documentary filmmaking and his unique experience shooting in Scottsboro, Alabama where his father, documentarian Leo Hurwitz, had shot nearly 70 years before.

Visually, when you approach a historical documentary as opposed to a feature film, are there differences in your approach or do you treat it much the same?

For features and for documentaries, the challenge is the same, I think, and it's that you have to tell a story with pictures. And that means that you use the elements of the picture, the lighting, the composition, the angle of the camera, to further the point in the story.

In shooting Scottsboro, the challenge was to take a subject that had already happened and in fact, was so daunting because there was such a minimum of recorded material about the case and do it in a way that people would want to watch and where the history could be made to live. I think evoking is one word that could describe what the challenge was.

[Producers] Danny [Anker] and Barak [Goodman], both were very clear that they wanted very strong images to evoke the time, evoke the feeling. I wasn't the only cameraman on the film. Buddy Squires was the other one and he did some beautiful work with a train which kind of - was the kind of central motif - visual motif that the film hung on.

Let's talk a bit about your father. What did he do and what is his background?

My father's name was Leo Hurwitz and he was one of the second generation of the pioneers of American documentary film. If you think that [Robert] Flaherty and Pare Lorentz were the first American documentarians, Leo Hurwitz, Paul Strand, Willard Van Dyke, several others, were the second generation of American pioneers in the documentary. He was a very political filmmaker and his early films were filled with social commitment and with the use of the film as a social document. Later in his life, his films had more to do with art and less to do with politics.

What was interesting about his life?

My father was born in Williamsburg, Brooklyn to a family of immigrants and somehow got the idea to take the test for the one scholarship that was given in the New York area to Harvard University. And he took the test. It was a Harvard Club Scholarship and he won it. So he went to Harvard. And I think it really was one of the formative experiences of his life, as a - and in addition to growing up on the Lower East - on the equivalent of the Lower East side in Brooklyn. And he got out of Harvard and graduated right into the middle of the Depression. There weren't any jobs in particular. He spent two or three years doing a bunch of different things. He was an editor of New Theater Magazine which was the journal of the - among other things, a group theater which was a tremendously seminal theatrical group in New York. It gave birth to the Method and brought [Konstantin] Stanislavsky to the United States. And he took still photographs and he began to think about making films. When he was at Harvard, he had written a letter to Charlie Chaplin asking him if he would work with him and Chaplin hadn't written back. So he'd given up on that and I think that - he doesn't ever say it but I have a feeling that if the Scottsboro boys film wasn't the first film that he ever did, it was very close to the first film that he ever did. Because he went down there in 1933, that was three years after he graduated from college.

The world that my father graduated college into was a world with a tremendous amount of grievances and a tremendous amount of hope at the same time, interestingly enough. Because of all this social movement in the United States, although there had been lots of union movements, but at this time it was beginning anew. I think that probably happens in America a lot. People felt that they were beginning things anew and that really they could change the world. And really at the center of this movement was the Communist Party which, either through itself or through organizations that it was in charge of or controlled, really spanned the progressive causes like the desire to fight Fascism as it was growing in Europe, like the growth of unions, like the desire to stop people from being evicted from their houses, and like the movement for racial justice. You can really say, I think, that with the exception of the traditional African American organizations like the Urban League and the NAACP, the Communist Party was the main organ for struggle against racial injustice in the United States at the time.

Let's move a little bit now to the story of your father going down to Scottsboro.

One of the most moving things for me about this film was the rhyme between my own experience with Scottsboro and my father's experience with Scottsboro. And it happened this way. When Danny Anker called me to work on this film, he said that he'd been looking for some footage that my father had shot in Scottsboro that he'd found reading some graduate student's work about my father. And I remembered my father telling me the story about his travelling down to Scottsboro, Alabama and Decatur, Alabama and shooting footage for a film about the Scottsboro trial. But I also remembered him saying that he didn't know where that footage had wound up and he was pretty sure that it didn't exist anymore. So I'll continue the story by narrating my own experience which is that I - we flew down to Alabama with Danny Anker and Barak Goodman and got in a car and we drove to Scottsboro.

So we came into town and Scottsboro is a traditional Southern town in that it has a county seat, in that it has a courthouse square - a big square, Victorian courthouse with cannons in front of it and a square of streets around the courthouse with the office buildings of the town and I guess probably the various offices - clerks and lawyers' offices that are involved with the courthouse and the county business arrayed around that. And we'd begun to make shots of the courthouse where the first trial took place. And it became clear to us that we really needed a high angle of this courthouse square. And we looked around to find the best building. We went up - I found it and there was a stairway that led up to a lawyer's office on the third floor. I walked up the stairs to the lawyer's office and asked them if we could make a shot from their window. They were a little bit kind of stand-offish but they finally agreed and I began to set up. I did make a shot but the window was locked shut. There was no way to open the window and there was really only one window that was - that would make that shot. So we didn't get as good a shot as we hoped. We made do in other ways and we got finished with shooting.

It was about sunset and we got back down and got into the car. And as we were driving out of town, Danny said to me, well, do you want to hear what your father says about shooting in Scottsboro? And I said, yes, I didn't know that there was... Well, what they'd done is they'd found an oral history that my father had done about this experience and Danny had transferred it to cassette tape and he popped it into - it was cued right up to the point which my father was talking about this exact experience. And he popped it into the cassette deck in the car and my father narrates his experience of coming into Scottsboro and driving around the courthouse square and stopping. He was with a bunch of other reporters, probably from various left-wing journals and looking for a place to make a good shot of the courthouse and he needed a high angle. So he went to a building - now it was the afternoon and the sun would have been right only from one side of the square in the afternoon. And he goes into a building and he goes up to the third floor to a lawyer's office and in fact, they had a window that looks right out on the courthouse. And he asked if he can make a shot from the lawyer's window and they tell him wait there. And he waits and he waits and he waits for two hours. And he tries to leave and they don't let him leave. They say, "No, you better stay here." And finally, they say, "OK, it's time for you to go now." And the sun has now gone down and it's almost dark. And they accompany him down to his car.

Now, there are several men and he sees that his other friends have all been put in the car and there's a group of men standing around the car. And they tell him to get in the car and they tell him to follow them. And they drive out of town - my father drives out of town following a car of men from the group that had taken him downstairs and behind him is another car following them. Now, he - this is a time when there were continued lynchings in the South, where there were union organizers that had been killed in the South in the years surrounding it, several, perhaps a dozen. And it was not unreasonable for them to fear for their lives. In fact, nothing happened. They got to the edge of town and the car pulled over and they went on down the highway. The car behind them followed them for a while and then let them go and they went on out of town and went to Decatur where the trial was. That was the story and I looked at Barak and Danny and I said, You know, we both chose the same lawyer's office. We both chose the same shot, my father and I, 60 years separated.

Did that inspire you to dig deeper into this story?

The next part of the story has to do with what happened in Decatur, Alabama. We also - the film also went to Decatur but there wasn't anywhere nearly the same kind of coincidence with my father there. But he had actually shot some footage. He claims he shot footage in the courtroom. He also shot footage of the boys being taken - the Scottsboro boys being taken in and out of the courtroom and of the National Guard arrayed around the courthouse. This footage must have been used as part of an attempt to raise money for the Scottsboro boys by the International Labor Defense and he says, in his own oral history, that he had been approached personally by the International Labor Defense to make this film and they had done it in connection with the Worker's Film and Photo League. I can only imagine that the film was taken around by individual relatives of the Scottsboro boys or - and organizers for the I.L.D. and shown to parties and fundraising events and all kinds of political things to raise money for the - the I.L.D. raised thousands and thousands of dollars for this defense and to pay the lawyers. But Danny searched and searched and searched and could not come up with this film. And he tried in Europe, in the French Cinemateque, which is often a repository of American documentaries that get away from America as well as - of course, he's searched all the American archives and the archives of various left-wing libraries. Couldn't find anything. He went to Russia and searched the archives of the Soviet Union and couldn't find anything. He tried searching for "Scottsboro", he tried searching for "African American", he tried searching for "black American", he tried searching for - he tried everything and then when he finally had almost given up hope, he said, wait a second. Why am I being so politically correct? And he went back and he searched under the word "Negro" and bing, up came some footage of the Scottsboro boys. And in fact, at that time, in the Soviet Union, the word "negro" was synonymous with Scottsboro boys. When the Russians thought about the American negro, they thought about Scottsboro boys because that was the international Communist movement's rallying cry at the time in terms of America and black America.

What do you think your father would have felt about this whole turn of events?

My father wasn't one to give coincidence a great deal of importance. But I think he would have very much liked the fact that I was working on a film on the same subject that he had and that his own footage had come back to help the project and that it had been located. I think, more than anything, he would have been delighted that the film was found.

My father was a very important person in my life. And he always stays with me. So more than inspiring me to dig deeper, it just allowed me to keep him a little bit closer with me. It was - and it was in some ways, a kind of an atonement between my father and me down there in Scottsboro, Alabama.