Agnes Conlon

As Thanksgiving approached in 1938, Seabiscuit’s jockey Red Pollard watched the world from a room at Boston’s Winthrop Hospital, wondering if his leg, shattered in a racing accident four months earlier, would ever heal. His muscular body had shrivelled to 86 pounds. For consolation, Pollard turned to an essay by one of his favorite philosophers, Ralph Waldo Emerson. Entitled “Compensation,” the essay presented Emerson’s belief that every condition in nature and life was balanced by its opposite. “A fever, a mutilation, a cruel disappointment, a loss of wealth, a loss of friends, seems at the moment unpaid loss, and unpayable,” Emerson wrote. “But the sure years reveal the deep remedial force that underlies all facts.”

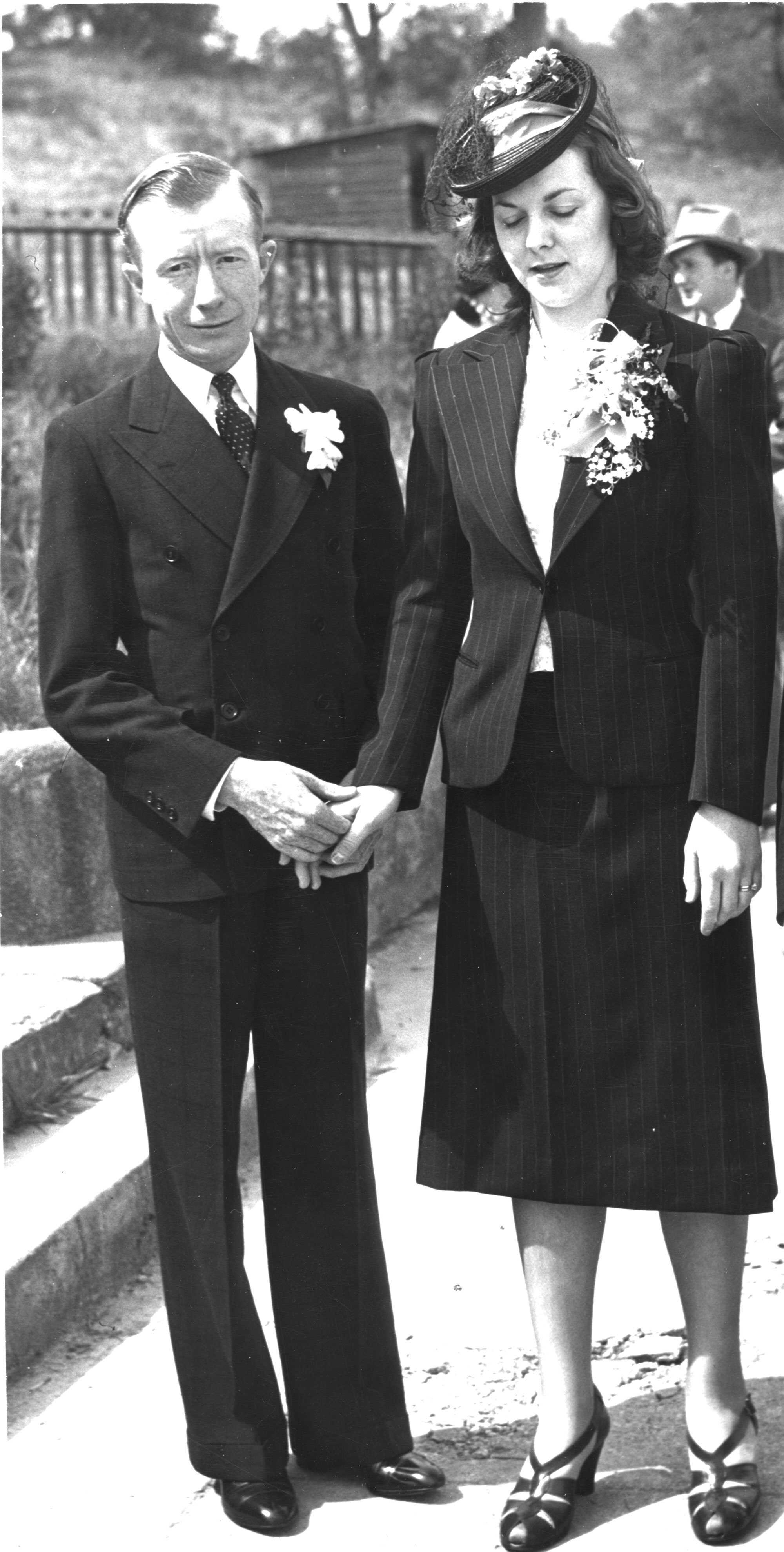

An Unlikely Proposal

For Pollard, that remedial force was Agnes Conlon, the private nurse who cared for him at the hospital. The daughter of well-heeled antique dealers, and a resident of Boston’s prestigious Back Bay neighborhood, Nurse Conlon was, by any measure, out of Pollard’s league. She was also already engaged to a successful doctor. But Pollard was smitten. He charmed Nurse Conlon with poetry, and confided his secrets, even telling her about the blindness in his right eye. Then, one afternoon, he asked Agnes to marry him. To the horror of her status-conscious family, Conlon’s answer to the unlikely proposal was “yes.”

In Love

“She had no clue what his real life was like,” says the couple’s daughter, Norah Christianson. “She always saw him in crisp white linen sheets and shaven, and I’m sure he watched his language. I think that his being famous at that point… didn’t influence her at all. They just fell in love with the barest environment and atmosphere. You know that was probably the only time when they would have been able to fall in love. I mean the racetrack life is so hurly-burly: fast money, drugs, booze, brawls, and she never would have found her way into that life.”

A New World

The two were married in the spring of 1939 at Ridgewood, the California ranch that belonged to Seabiscuit’s owner, Charles Howard. Over the following months, Conlon got to know her husband’s world. She hung around the barns with him, and got comfortable with the horses. She learned of the terrible struggles her husband — like almost all jockeys — went through to keep his weight down. She also discovered that to dull the continuing pain in his shattered leg, Red had become an alcoholic.

Uncertain Future

In the fall, Conlon told her husband that she was pregnant. Pollard, who had wandered from track to track his entire life, must have found the news both exhilarating and terrifying. He had no money, no home, and at best an uncertain future in the only profession he knew.

Joyous Days

Few expected Pollard to ever ride again, but on February 23, 1940, Pollard climbed aboard Seabiscuit once more, this time for the race that had long eluded the horse, the Santa Anita Handicap. On race day, Agnes hung a Saint Christopher medal around her husband’s neck for good luck. That afternoon, as she watched Pollard and Seabiscuit careen across the finish line far ahead of the rest of the pack, Agnes sobbed with joy. A few months later, the couple’s daughter Norah was born; a son, John, would follow a few years later.

Seeking Stability

After the race, Pollard, coping with what he called a “nervous reaction” to the strain the race had placed on him, vowed never to race again. But his promise was short-lived, and he re-entered the life he loved. Conlon wanted a home to provide stability, and they bought a small one in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Red’s career followed a slow decline back to the minor leagues of racing, which he had left when he joined his fate with Seabiscuit’s. Over the years, the jockey was plagued by a never-ending series of spills and injuries, which included a broken hip that left one leg shorter than the other and a head injury that cost him a jigger-full of teeth — and nearly his life. Conlon persevered, yet began to fear the ring of her own telephone, afraid it would bring more bad news of another accident. She prayed for his safety, but never begged him to leave his first love, racing, for another career. She understood that much of her husband’s life force came from the thrill of riding a galloping horse, whether or not he could win.

Last Days

In 1980, Conlon was hospitalized with cancer. Pollard’s decline had been more gradual. His collective injuries from a lifetime of racing had left him unable to take care of himself, especially with Agnes’s illness, and his children had to place him in a nursing home. His wife was with him when his body, battered by a lifetime of accidents, surrendered in 1981. Agnes, his unlikely partner of 42 years, died two weeks later.