Charles Howard

As a young man, Charles Howard was drawn to the adventure of war. Hoping for a chance to fight in the Spanish-American War, he enlisted in the cavalry. He never made it to the battlefield, but his training at Alabama’s Camp Wheeler turned him into a skilled horseman. After his discharge, he switched from horses to bicycles, taking up competitive bicycle racing and working as bicycle mechanic in New York City. He married and had two children. Then, adventure called again. At age 26, he arrived in San Francisco with just 21 cents to his name in hopes of making a name for himself in the West. He promised to send for his family when his pockets had more jingle.

Entrepreneurial Beginnings

Charles Howard started in the bicycle business, just like his famous contemporaries Carl Fisher and Wilbur and Orville Wright. In San Francisco, Howard somehow scraped up enough money to open his own repair shop. Soon he was fixing more than just bikes. Worried-looking men with money to burn began appearing at his door, wondering if he had any experience with an expensive, often unreliable new contraption called an automobile. Howard saw a golden opportunity.

Betting on the Future

In another bold move, Howard bet on the future of the automobile, buying a ticket to Detroit. There he finagled a meeting with Will Durant, the owner of Buick Automobiles and future founder of General Motors. Durant sent him back home to establish dealerships and soon Howard, at age 28, was in charge of the Buick franchise for San Francisco.

Cars to the Rescue

Success was not immediate: for months he could not sell one of his first three cars. It took a disaster, the San Francisco earthquake of April 1906, to launch the young man’s success. Wagon horses, injured by the initial collapse of buildings and terrified of the ensuing fire, could help little with rescue efforts. Howard’s three unsold cars became the first four-wheeled ambulances in the city, shuttling the injured to rescue ships docked in the bay. It was a coup for the automobile, and Howard was determined to capitalize on it.

Daredevil Marketing

After the rubble was cleared, Howard had lost his building, but still had his three cars. With the insurance money he could have quit the car business, but he was ready to take on a challenge. Howard began racing his Buicks and performing daredevil feats to attract the interest of the press. His customers could buy the same models they had seen at the race track — and they could trade in their horses, too. The scheme worked: Howard sold 85 cars in just one year, at the astronomical price of $1,000 each. In 1909, Durant showed his gratitude by giving him control over all distributorships in the western United States.

Tragedy

By the 1920s, America was in love with the automobile, and the federal government was spending millions to construct roads. Howard was a rich man, yet his wealth couldn’t protect him from tragedy. In 1926, the automobile tycoon’s 15-year-old son, Frankie, driving one of his father’s old trucks, swerved to avoid a rock and died after toppling into a canyon. To memorialize his son, Howard built the Frank R. Howard Memorial Hospital in Willits, California. He would remain on the hospital’s board for the rest of his life.

Midlife Changes

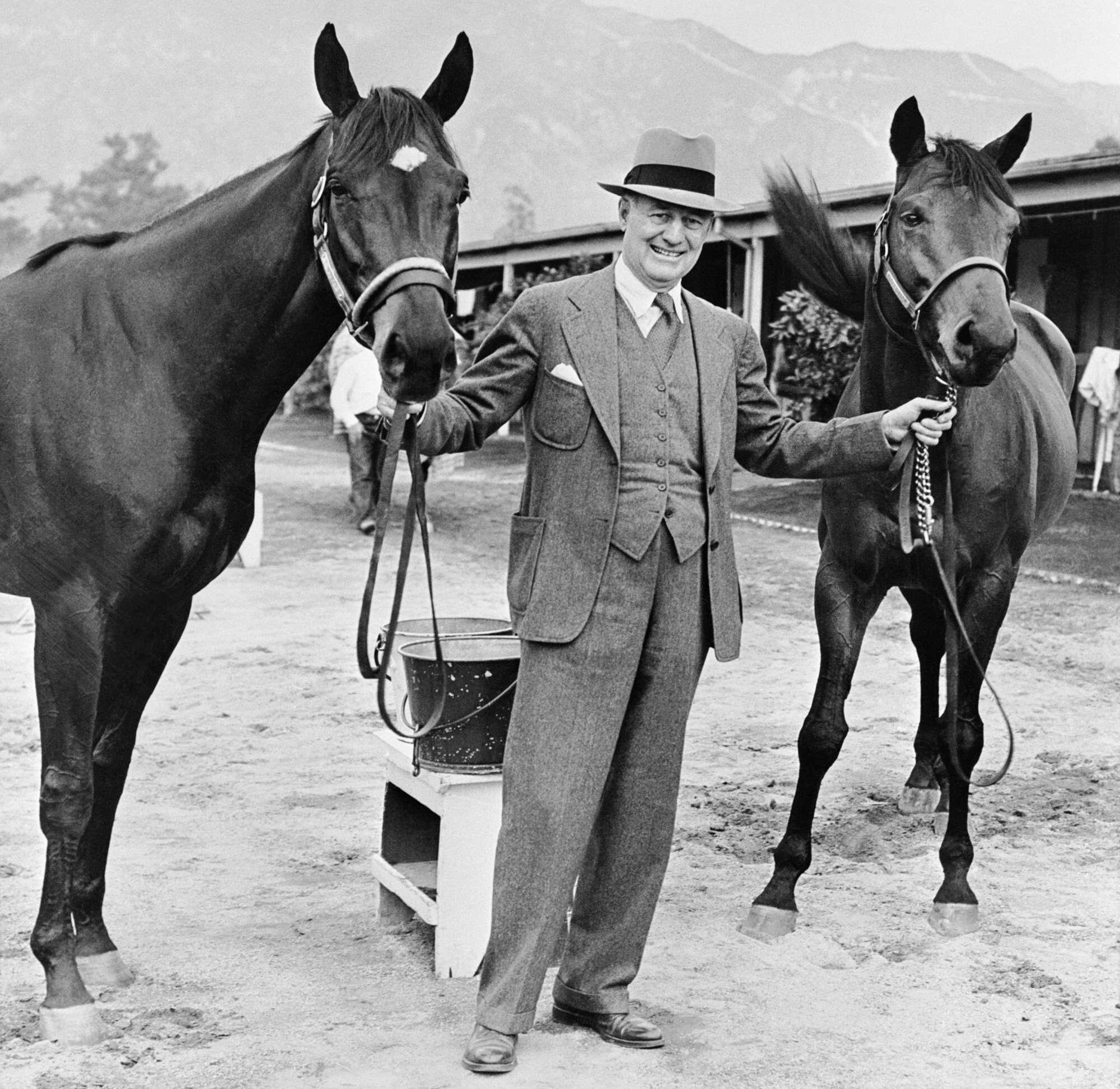

Whether out of grief, out of a growing disinterest in cars, or because his marriage had grown lifeless, Howard began traveling south to the Tijuana horse races. His life would change dramatically when at age 52, he fell in love with Marcela Zabala, the older sister of Howard’s daughter-in-law Lin. The young actress, who was 25, shared his passion for horses. They married in 1932. In 1934, Howard and his friend Bing Crosby, among others, invested in the construction of Santa Anita Park, one of the era’s finest racetracks, outside of Los Angeles.

Unlikely Victor

In August 1936, while Howard and Marcela were at Saratoga Race Course bidding on yearlings for Crosby, they took in a few races. Howard asked his wife what she thought of a rather small, mud-colored horse. She said he would lose, and bet him a cool drink that she was right. The horse, in an out-of-character performance, led from wire to wire, and Howard, acting on a feeling in his gut and the approval of his trainer, bought the horse for $8,000. His name was Seabiscuit.

Superstar

Howard, who adored his horse, rode Seabiscuit’s fame for all it could deliver. “He was not content with mere greatness for his horse,” according to author Laura Hillenbrand. “For Seabiscuit, he wanted superstardom, in his own age and in history.” To make sure the horse got his due, Howard badgered and charmed reporters with letters and phone calls, and even sent them oversized Seabiscuit Christmas cards.

His Favorite Horse

While Howard had other thoroughbred successes after Seabiscuit, none of the other racers ever touched him the way that horse had. When Howard’s heart proved too weak to endure the excitement of the racetrack, he would still sometimes saddle up his favorite horse and they would walk his beloved Ridgewood ranch, located north of San Francisco.

Last Years

On the morning of May 17, 1947, Marcela told her husband that Seabiscuit, at the relatively young age of 14, had died. Howard, so often a public man, secretly buried his greatest horse and planted an oak sapling to mark the spot. He told only his family where the gravesite was. Three years later, the heart of the man who began his career fixing broken bikes and cars broke down for good. Howard was 72 years old.