Red Pollard

John Pollard was born in 1909 and raised in Edmonton, Alberta, in the western reaches of the Canadian wilderness. The second of seven children born to a bankrupt Irish brick manufacturer, Johnny — as he was known to his family — grew up in a boisterous home. He was passionate about athletics — particularly boxing — and so fond of literature and poetry that he was known to challenge his sister Edie over who was better at memorizing literary passages. But his greatest pleasure by far came from his horse, Forest Dawn. To help his family make ends meet, Johnny took to delivering groceries with his toboggan hitched to the little horse. By the time he was in his early teens, he had decided that he wanted to be a jockey.

Wandering

When he was fifteen, Pollard left home in the care of a guardian and went off to pursue his dream. Within a year, the guardian had abandoned him at a makeshift racecourse in Butte, Montana, and the boy was on his own. He spent the next couple of years wandering around the country’s lowliest racetracks, trying to talk his way into a saddle. He was tall for a jockey — about five feet seven inches in his stocking feet — and though he managed to ride often enough, he never won a single race. Eventually, he began moonlighting as a boxer, using the ring name “Cougar.” But most people knew him as “Red,” a nickname he earned for his shock of flame-colored hair.

Books as Companions

Horse racing is a seasonal sport, and Pollard was always on the move, traveling to Canada in the summer, California in the fall and spring, and then to Tijuana in the winter. His only constant companions were his books — well-worn leather pocket volumes of Shakespeare, Robert Service’s Songs of the Sourdough, and a Ralph Waldo Emerson collection. He barely earned money enough to eat, and spent most nights sleeping in horse stalls, but according to his sister Edie, Pollard was “happy as heck.”

Troubled Horses

In 1927, Pollard was sold — young jockeys were considered property — to a horseman named Freddie Johnson, who handed him over to his trainer, Russ McGirr. Although Red was still losing far more often than he won, McGirr discovered a rare talent in the boy that would help carry him into racing history. After years of riding the worst mounts on the worst tracks in the racing circuit, Pollard had come to understand troubled horses. He was kind to them, avoiding the whip, and his mounts often responded to his gentleness by running hard.

Partially Blind

Despite that gift, however, Red continued to have only a middling career. Some of his failures were doubtless the result of an accident he had had sometime early in his career. While exercising a horse around a crowded track one morning, he had been hit in the head by something kicked up by another horse’s hooves. The blow damaged the part of his brain that controlled vision, permanently blinding him in the right eye. “Without bifocal vision,” explains author Laura Hillenbrand, “you don’t have depth perception. So he couldn’t tell how far ahead of him horses were. He couldn’t tell how close he was cutting it. But he knew no fear. He rode right into the pack with one eye.” For the rest of his life, Pollard kept his blindness a secret, knowing that if track officials found out, they would never let him ride.

Lucky Day

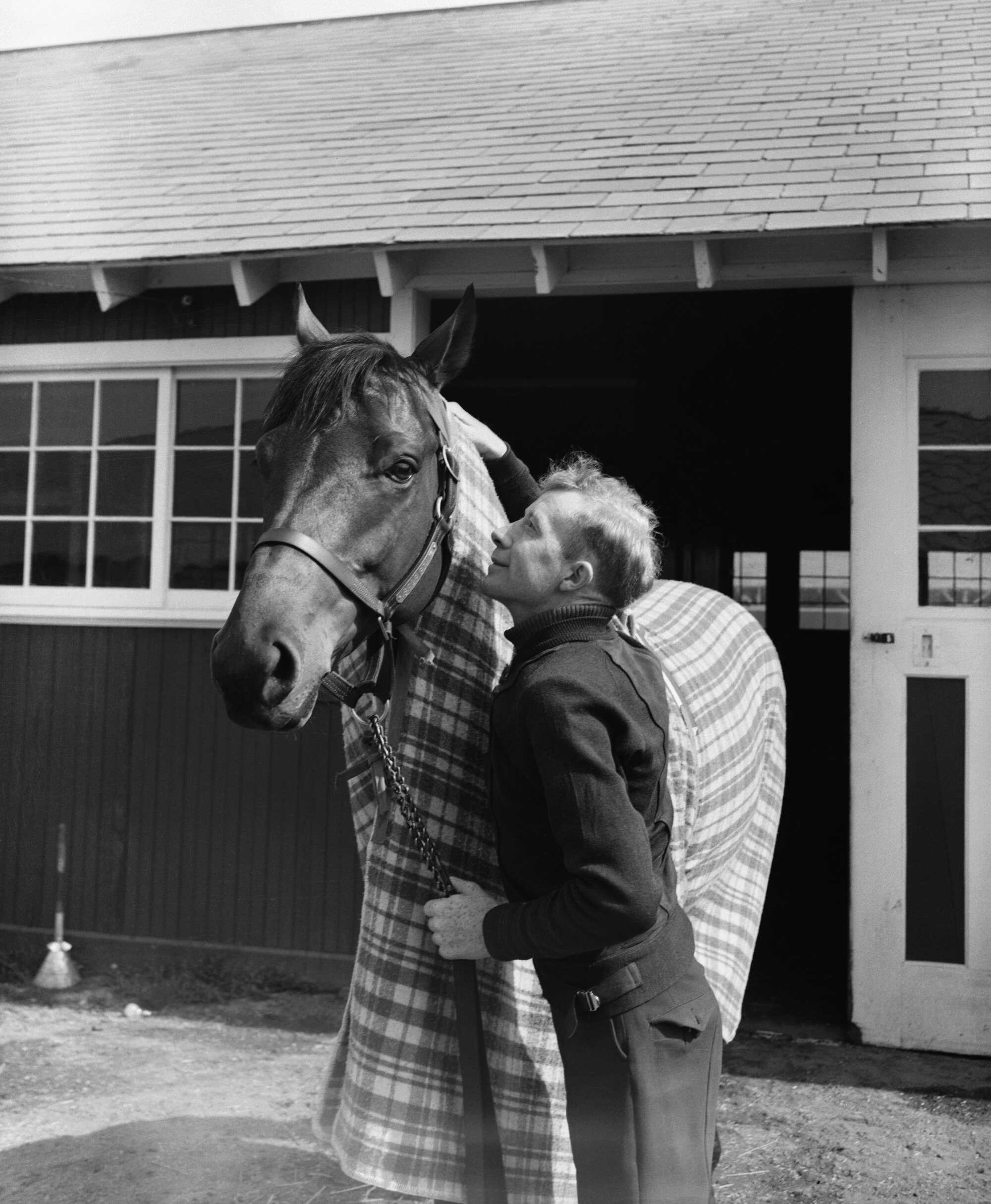

By the summer of 1936, twelve years of bad luck and failure had begun to take their toll. Like many Depression-era unfortunates, Pollard was broke and homeless. That August, he was heading north with his agent — a squat, hare-lipped man named Yummy — when a freak car accident left them stranded outside of Detroit, with nothing but twenty cents and a half-pint of a cheap Whisky they called “bow-wow wine.” The two men hitchhiked to the Detroit Fair Grounds, where Pollard bumped into Tom Smith, Seabiscuit’s trainer. As it happened, Smith was looking for a jockey. When introduced to the temperamental, often unruly horse, Pollard offered a sugar cube. Seabiscuit touched the jockey’s shoulder in a rare gesture of affection. As Smith saw it, Seabiscuit had chosen his jockey. It might have been the luckiest day of Pollard’s life.

Plagued by Injuries

For a time, Pollard and Seabiscuit lit up the racing circuit, capturing win after win in races across the country. But the injuries that plagued Red throughout his career unseated him from the celebrated thoroughbred more than once. In February 1938, he was almost crushed to death in a horse pile-up at the San Carlos Handicap. It took months to recover. No sooner was he back in the saddle than an inexperienced horse spooked during a workout and crashed into a barn, nearly shearing off Pollard’s leg below the knee. The broken leg wouldn’t heal properly and would keep him from riding Seabiscuit in the famous one-on-one match-up against War Admiral on November 1, 1938.

Hopelessly in Love

While Pollard recuperated at Boston’s Winthrop Hospital, wondering if he would ever race again, he fell in love with his private nurse, a refined Boston native named Agnes Conlon. The restless jockey and the prim, well-heeled nurse were an undeniably odd match, but they were also hopelessly in love. When Pollard asked Agnes to marry him, she defied her family’s wishes and said “yes.” They would have two children and live together for over forty years.

The Greatest Ride

The highlight of Pollard’s racing career came in 1940, when he rode Seabiscuit to victory in the race that had twice eluded the horse, the Santa Anita Handicap. “I got a great ride,” Pollard said afterwards. “The greatest ride I ever got from the greatest horse that ever lived.” Seabiscuit was retired almost immediately after the race, and Pollard soon did the same. But he couldn’t stay away from the jockey’s life for long. He soon returned to the racing circuit, and was twice hospitalized after terrible accidents — he broke a hip in one spill and his back in another. After Seabiscuit, the jockey never had much success, falling back to the bush leagues of racing from which he had emerged.

Retirement

Finally, in 1955, at the age of 46, Pollard hung up his silks and retired for good. For a time, he worked sorting mail at the track post office, and then as a valet, cleaning boots for another generation of riders. He died in 1981, but what exactly killed him was unclear. According to his daughter Norah, “he had just worn out his body.” Agnes, sick with cancer, died two weeks later.