The Japanese-language chart-topper has seemingly sparked a thousand covers — but most obscure the song’s complex geopolitical history.

By Elaine Kathryn Andres

Growing up, family parties would wind down around our favorite special occasion appliance. My father clumsily ran cables from the karaoke machine into our television, transforming the living room into our own after-hours bar. I’d sit entranced by the tinny electronic piano and synthesized strings, the Ken Burns effect moving dreamily over nature scenes overlaid with lyrics. The words on the screen felt latent with possibility in the moment before they changed from white to blue.

My first taste of “Sukiyaki” was on such a night. Basking in the glow of the tiny Toshiba, I attempted my own rendition of the 1963 chart-topper that has seemingly sparked a thousand covers. In the hands of artists like Jewel Akens, A Taste Of Honey, and Selena, “Sukiyaki” has been born again (and again) as a song about lost love. And while these renditions typically hint (in inevitably reductive ways) at the tune’s Japanese origins, they obscure the song’s much deeper geopolitical history.

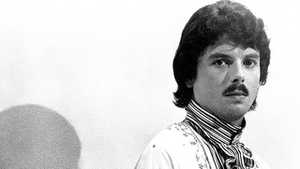

Far from a ballad about a beef dish (as the arbitrary English title might suggest), the original Japanese-language cut was titled “Ue o Muite Arukō,” or “I Look Up as I Walk.” Recorded by crooner Kyu Sakamoto and written by lyricist Rokusuke Ei and composer Hachidai Nakamura, the song is a product of the post-war Japanese pop scene, its creators part of a generation of Japanese youth whose culture was dramatically changed by World War II.

The 1945 U.S. Occupation of Japan opened the island nation to western influence as never before. Lifting the imperialist regime’s wartime media restrictions, American authorities encouraged cultural diplomacy through the so-called “3-S strategy”: screen, sports, and song. And with the rise of air travel, multinational record labels like Capitol and RCA could distribute music globally with ease. Sakamoto would draw his performance repertoire from a steady diet of Paul Anka, Bobby Darrin, and Elvis, by way of the Far East Network, an American military radio station serving U.S. forces in Japan, Okinawa, the Philippines, and Guam. He even got his start during the rockabilly boom in Asia, performing renditions of “Hound Dog” and “G.I. Blues” in clubs and mess halls for troops on U.S. military bases.

But even as some elements of American culture were embraced, many in Japan chafed against the new foreign pressure. “Ue o Muite Arukō ” captures just such a sentiment. Describing a lonely, tearful, yet determined walk under the clouds, the lyrics lament Rokusuke Ei’s mounting frustrations at the futility of the massive student-led protests against the continued U.S. military presence in his country. Despite opposition from youth and trade union members, Japan had signed the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security on January 19th, 1960. The revised treaty reaffirmed and reinvigorated the military and economic intertwining of Japan and the U.S., locking in American airbases in Japan and Okinawa as key strategic outposts for U.S. Cold War policy in Asia.

Ei’s mournful lyrics paired with Nakamura’s up-tempo orchestral accompaniment in pentatonic major (a common scale in Japanese folk music), and Sakamoto’s hiccup-laden enunciation (characteristic of rockabilly), sounded the tension between feelings of loss and promise at this point in U.S.-Japan relations. At the same time, the resounding success of “Ue o Muite Arukō ” anticipated what would become a long, strategic legacy of pop culture traffic between these two world powers.

But before the song triumphed on American shores, it had to be baptized with its English-language name. That came courtesy of Louis Benjamin at the U.K.-based Pye Records, who reissued Sakamoto’s original recording in the Great Britain in 1962 with the title changed to “Sukiyaki.” The entirely unrelated “translation” was an easier to pronounce, albeit unmistakably Japanese alternative, that would further capitalize on the balance between sonic familiarity and Orientalized difference for an international market. West Coast deejays began adding the track to their rotations in early 1963, leading to a wide release by Capitol Records. It reached number one on the American Billboard Hot 100 in June and would remain at the top spot for three consecutive weeks as one of the few non-English language songs to do so, and the only Japanese-language hit to top the charts to date.

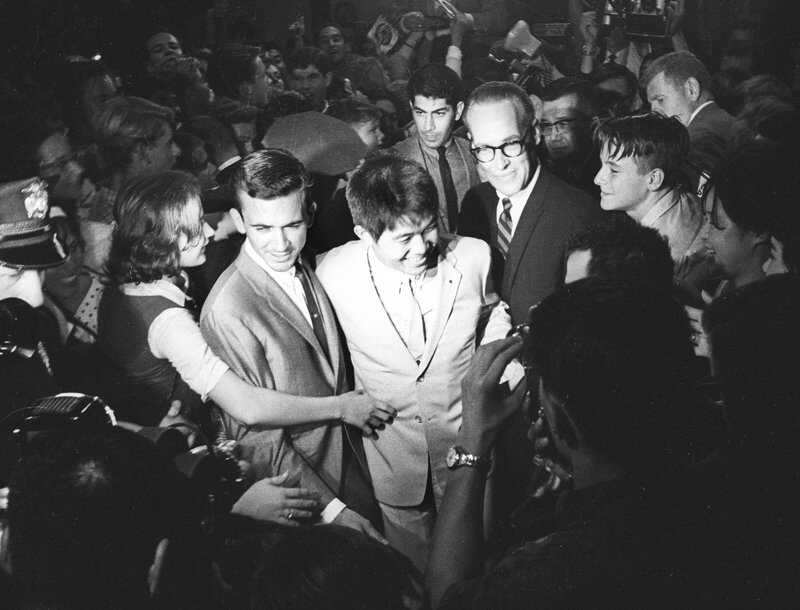

Riding his crossover success, Sakamoto embarked on a global tour that included an August appearance on The Steve Allen Show. His wholesome image and swoon-worthy performances won the hearts of screaming teens at Los Angeles International Airport. It also served the ongoing effort to recast Japan as a knowable and, importantly, non-threatening ally to an American public tuned to mistrust the nation in the wake of World War II. Moreover, the widespread fixation on Sakamoto’s soft, racialized masculinity helped consolidate the “model minority myth” that has been used to different ends during the ongoing civil rights movement.

Ultimately, the success of Sakamoto’s “Sukiyaki” symbolically announced Japan’s reentry as a rising industrial nation on the global stage — a reentry that ensured nearly every Olympian (and fan) at the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo could likely hum Nakamura’s infectious melody. Japanese firms would become major players in technology and manufacturing, precipitating the arrival of that karaoke machine in my living room. And Japanese culture in its many forms (however exoticized) would become a deep fascination for a diverse American public. In the end, having traveled by air and airwaves across shores and genres, with new meanings in each re-sounding, “Sukiyaki” arrived as a standard on my family’s karaoke nights with its distinctive flavor intact.

Listen to the complete top ten from the summer of 1963 on Spotify.

Elaine Kathryn Andres is a musician, record collector, and third-year doctoral student in the program in Culture & Theory at UC Irvine. Her research examines musical scenes along U.S. circuits of empire through the lives and performances of popular multiracial Asian American cross-over artists. She has recently contributed to a book entitled Sex & Colonies (Groupe de Recharche ACHAC, forthcoming) and has published writing in the Journal for Asian American Studies.

Roll down the windows, turn up the volume and prepare to sing along as American Experience celebrates the music of the season with Songs of the Summer.

In 1958, Billboard launched its Hot 100, chronicling the songs that were flying off record store shelves, playing non-stop on juke boxes, and blaring through radio speakers. Almost sixty years on, how we listen to music and how we track a song’s success may have changed, but music remains a powerful force in our culture. Every Friday from June 2 through August 25, we’ll reveal one iconic song that hit the charts, accompanied by commentary from some of our favorite music writers. Explore our historical mixtape, and check back each Friday for our next track.

Published June 9, 2017.