How a Small Band of Students Set off the Iran Hostage Crisis

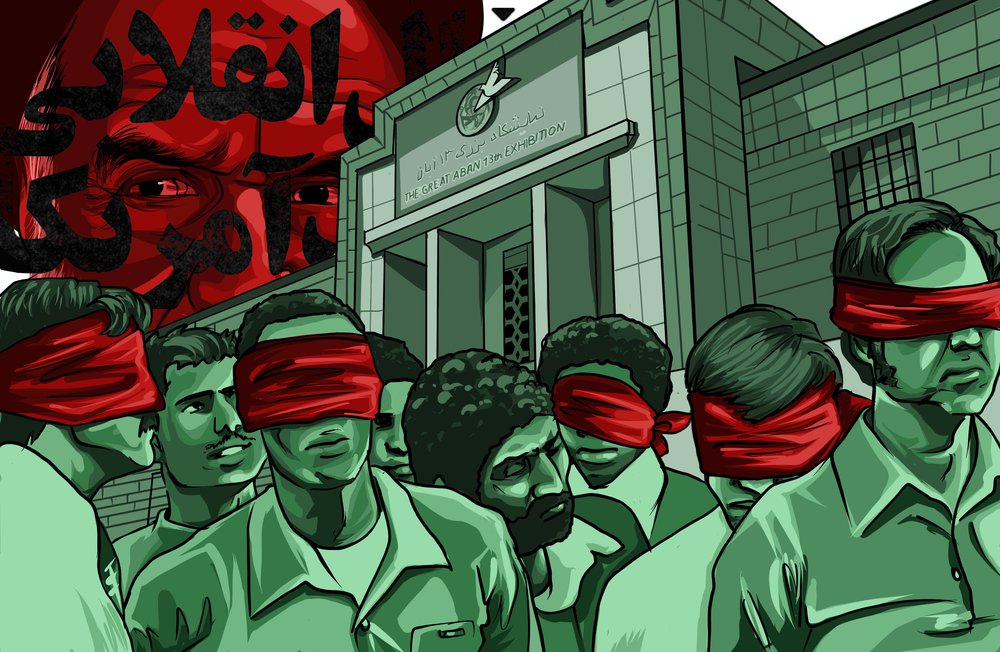

Who was behind the U.S. embassy takeover in 1979?

According to one of the Iranian students who seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran in November 1979, the United States provoked action against its diplomats with one fateful decision. On October 22, President Jimmy Carter had allowed Iran’s deposed leader, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, admission to the United States to receive medical treatment for cancer.

The students saw Carter’s decision as evidence of U.S. intent to undermine the populist revolution that had ousted the Shah earlier that year. “By allowing the Shah to enter the U.S.,” a student named Mohsen announced at a planning session two days before the embassy takeover, “the Americans have started a new conspiracy against the revolution. If we don’t act rapidly, if we show weakness, then a superpower like the U.S. will be able to meddle in the internal affairs of any nation in the world.”

The students had reason for their mistrust. It was American intervention in their country that had undermined Iranian democracy and placed the Shah in a position of absolute power in the first place. In 1953, in concert with British intelligence, the CIA had contrived a coup against Iran’s elected government and its Prime Minister, Mohammed Mosaddegh.

The United States then served as a key supporter and enabler of the Shah’s dictatorial rule for the next quarter century. Over the course of six American presidencies, even as the Shah’s regime grew increasingly despotic, the U.S. sold more military equipment to Iran than any other country. And Iranians lived in terror of the Shah’s secret police, known as SAVAK (and trained by America’s CIA and Israel’s Mossad), whose forces imprisoned, tortured and killed dissenters. All the while, resentment toward the Shah and his American backers built up—and eventually erupted.

The Iranian Revolution began in 1978, with students among its most ardent activists. The country’s universities, long sites of political ferment, became staging grounds for anti-government operations. Students demonstrated in Tehran, the Iranian capital, chanting “Marg bar Shah,” or “Death to the Shah.”

After more than a year of increasingly violent protests demanding the end of the Shah’s rule, he fled Iran into exile in early 1979. With the Shah gone and the army in disarray, the country fell into a state of near anarchy as a number of political factions vied for power, the most organized of which was an Islamist movement led by the cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

When word of the Shah’s grave medical condition reached the White House in October, President Carter was persuaded by his cabinet—and against his own judgment—to allow the Shah to enter the United States for medical treatment. In response, over a million Iranians took to the streets of Tehran. Now, the enormous crowds gathering around the U.S. embassy’s front gates, at the center of the capital city, had a slightly modified message to shout at the U.S. diplomats. “Marg bar Amrika!” came the new refrain, a message requiring no translation for the American personnel inside the compound.

Several days later, on November 2, around a dozen students representing the city’s four major universities secretly convened to plot a dramatic next action against the United States. Mohsen, who studied civil engineering at Tehran Polytechnic, laid out the plan to his peers: “What we are proposing is a peaceful occupation of the American Embassy…This will mean taking the embassy personnel hostage not as diplomatic personnel, but as agents of the American government. They are deeply involved in their government’s conspiracies in any case. By intervening in our national affairs even now after the revolution, they have undermined international conventions.” Thinking it would be a relatively short affair—an essentially symbolic takeover lasting three days, to make their point to the world—the students’ plan only accounted for several days’ provisions.

Referring to themselves as “Muslim Students Following the Line of the Imam,” thus directly identifying themselves with Khomeini and his religious agenda, the group made reconnaissance trips to and around the embassy in preparation for the takeover. The next day, Khomeini issued a public statement that seemed to the students an incontrovertible endorsement of their plot. “It is incumbent upon students,” Khomeini decreed, “to expand their attacks against America and Israel. Thus America will be forced to return the criminal, deposed Shah.”

At 10 a.m. on Sunday, November 4, the students assembled on Taleghani Avenue, the wide road in front of the U.S. embassy, holding a banner reading “Allah-o Akbar,” or “God is Greater.” The Iranian police at the front gates stepped aside. Women pulled bolt-cutters out from beneath their hijab and cut the chains holding the gates shut. The students walked in.

From there they fanned out to find embassy personnel and secure the compound. Barry Rosen, the embassy’s Press Attaché, recalls the moment he was taken hostage. “Before I knew it, 15 to 20 people are pounding on my door,” Rosen told American Experience. “They just barged through. There I am facing these people. I said, ‘who are you?’ And [one of them] says, ‘I’m a part of the Students Following the Line of the Imam. You’re in the nest of spies. You are part of U.S. imperialism, and you’re the corruptors of the Earth. You are our prisoner.’” Though several staff escaped, by the end of the day, the students had taken 63 Americans hostage.

Massoumeh Ebtekar, one of the student protesters who arrived at the embassy three days after it was seized, shared her own recollection of the event in a memoir years later: “When we took over the embassy, we were so convinced of the justice of our cause that nothing could stand in our way… a handful of students had burst into the inner sanctum of a superpower and humbled it.” Contrary to some of the hostage-takers’ original non-violent intentions, others immediately began threatening the hostages’ lives.

To the United States and much of the world, the hostage-taking was a flagrant violation of international diplomatic conduct; to the Islamic revolutionaries who had carried it out, theirs was a righteous act carried out “in the name of God,” the same words with which they often opened conversation with one another. Still, years later one of those former students admitted how little they had anticipated the implications of what they had done. “We lost control of events very quickly—within 24 hours,” Ibrahim Asgharzadeh, one of the initial planners, told a journalist in 2004, 25 years after the crisis. “Unfortunately, things got out of hand and took their own course. The initial hours were quite pleasant for us, because [the protest] had a clear purpose and justification. But once the event got out of its student mold and turned into a hostage-taking, it became a long, drawn-out and corrosive phenomenon.”

In the coming weeks and months, Ebtekar would become the students’ most prominent spokesperson to the outside world. Selected by the students for her English language ability—she had attended nursery and elementary school in the U.S., while her father earned his doctorate at the University of Pennsylvania—Ebtekar became known as “Mary” to the hostages. “Sister Mary was there to interrogate most of us,” Rosen recalled. “Accusing us, threatening trials. I had very negative feelings toward her. I just felt that she brought out the worst in me.”

The students entered into a new phase of the event, one ruled by round-the-clock news coverage and Khomeini’s public position: Unless the U.S. was prepared to extradite the Shah to stand trial in Iran, there was nothing to negotiate about. Carter was equally clear about the American stance. “The actions of Iranian leaders and the radicals who invaded our embassy were completely unjustified,” Carter stated just over a week into the occupation. “They and all others must know that the United States of America will not yield to international terrorism or to blackmail.”

As the crisis unfolded, the students demonstrated an increasingly sophisticated understanding of international media, issuing frequent public statements—sometimes up to five or six per day—and holding regular press conferences. It was at one of those conferences that Ebtekar, seated below an image of the Ayatollah, provided the students’ more militant, unified stance. “The hostages are in our hands, and we are ready so that in the case of any military intervention, we will destroy them,” she announced.

During the deadlock of the months following the initial takeover, the students-turned-professional wardens focused on another effort. The hostage-takers had made a priority of locating all documentation within the compound. With obsessive attention, they then turned not just to translation but to physically reassembling all of the shredded documents they were able to recover. As the crisis stretched out for one year and more, those students still involved in keeping the hostages captive turned to making the documents openly available. These would be published in Iran over the next 40 years, in more than 70 volumes, as “Documents from the U.S. Espionage Den.”

Ultimately, after 444 days, the Iranian government—with Khomeini as its first Supreme Leader—agreed to release the American hostages. In the end, resolution to the crisis depended not on the students who instigated it. Rather, the political actors whose power the students helped consolidate carried out the final negotiations. “We students were never informed of, involved in or consulted on the implementation process,” said Ebtekar, who eventually became Iran’s vice president for women and family affairs. “But all things considered, I felt that we had done well. We had accomplished something vitally important: We had shattered the image of American superiority in the world.”