Capturing the Sun Queen

How Mária Telkes and her radical design modeled a new future.

This article is the fourth in a series called A Thousand Words, where we feature an interesting image from one of our films alongside an essay about why that picture is worth, well, a thousand words.

Celebrated LIFE Magazine photographer Ralph Morse captured scores of notable Americans—actress Audrey Hepburn posing with the Oscar she won for the film “Roman Holiday,” baseball legend Jackie Robinson stealing home base at the 1955 World Series, astronaut John Glenn suiting up for space—but before all of them came the “Sun Queen,” and her house.

In the winter of 1949, LIFE sent Morse to Dover, Massachusetts to train his lens on Mária Telkes, a Hungarian-born inventor and chemical engineer who earned that regal nickname for her relentless pursuit of solar technology. As a freshman at the University of Budapest, Telkes had read a book called Energy Sources of the Future, about the sun’s vast potential to meet human energy needs. “This was the deciding moment,” she said later. “The book described experiments, mostly conducted in the United States, and therefore this was the place for me.”

After receiving her doctorate in physical chemistry in 1924, Telkes immigrated to the U.S., where she worked as a biophysicist at the Cleveland Clinic. She then joined Westinghouse Electric as a research engineer, developing thermocouples that could transform heat energy into electricity. While at Westinghouse she heard about an initiative at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that aligned with her desire to harness the sun’s power. She wrote to MIT’s solar project asking for a job, and when hired in 1939, became the project’s sole woman.

It wasn’t only gender that differentiated Telkes from many of her colleagues. While they focused on academic analysis, she was practical-minded; Telkes was interested in the widest real-world applications of solar-powered technology. She was also strong-willed, and her penchant for self-promotion put her at odds with the MIT project’s leadership. Finally, Telkes decided to forge her own path—and found two new collaborators.

She identified a patron in Amelia Peabody, an heiress who owned hundreds of acres in Dover, Massachusetts, a rural town about 45 minutes outside of Boston. Years earlier, Peabody, who was also a sculptor, had commissioned Boston architect Eleanor Raymond to design a sculpture studio on her Dover estate. Like Telkes, Raymond was herself a pioneer in a nearly all-male field. The three women now teamed up to realize Telkes’s ambition: a home relying on nothing but the sun for its heat.

The main challenge vexing MIT’s theoreticians and pragmatists alike was the question of energy storage. Capturing the sun’s heat was one thing, but storing it for use on cloudy days was, Telkes noted in a 1949 paper, “the critical problem.” She saw a potential solution in phase-changing materials—chemical compounds that held or released heat when changing form from solid to liquid, and back. Specifically, Telkes was interested in a substance called Glauber’s salt.

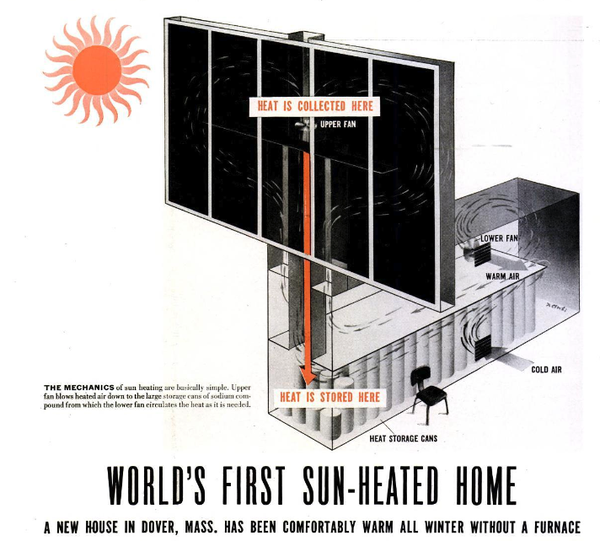

A sodium form of sulfuric acid given the name sal mirabile, or miraculous salt, by the German scientist who first synthesized it, Glauber’s salt was solid until it reached 90o Fahrenheit, at which point it liquified. When the salt cooled down again, it recrystallized, releasing all of the stored heat it absorbed. In the Dover design, Telkes placed 4,275 gallons of the salts in drums inside the home’s walls; fans then blew the hot air through the house via ducts.

On Christmas Eve 1948, the home’s new inhabitants moved into what came to be known as the Dover Sun House. The two-bedroom structure was wedge-shaped with its living areas on the first floor. The second story consisted of 18 windows facing south, for maximum sun exposure. Behind the windows were black painted panels to maximize absorption of the sun’s rays; this solar-generated heat was then used to heat up the Glauber’s salt, which then performed its miraculous task. Telkes had succeeded in realizing the world’s first fully solar-powered home.

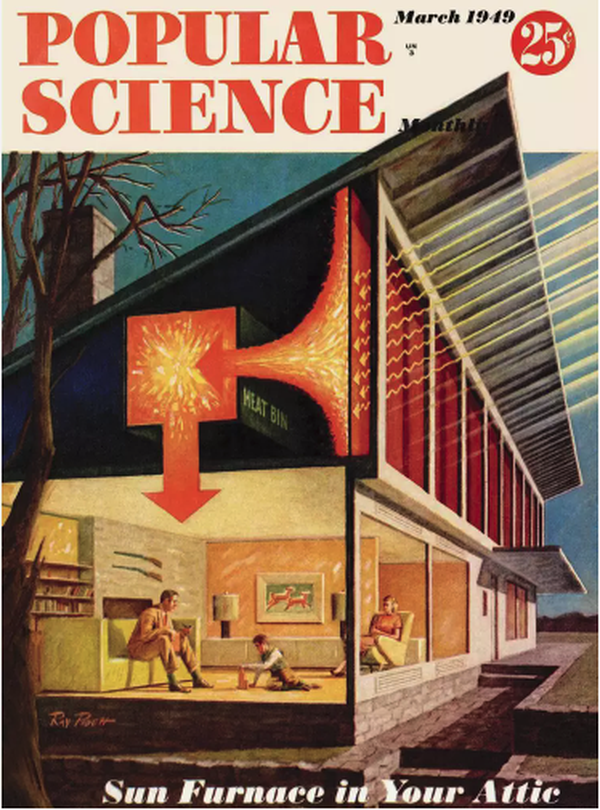

The Sun House quickly became a landmark. Twice a week, thousands of visitors arrived for tours. The media also came calling. LIFE sent its top photojournalist to capture Telkes’s brainchild, which struck as dramatic a pose in its environment as she did in her fur coat before it. “Its stark, modern lines stand out in the New England countryside,” noted the May 1949 issue of Popular Science, which featured an illustration of the home on the front cover. Andrew Nemethy was three years old when he and his parents took up residence in the Sun House. “By mid-century architectural standards, it might as well have been dropped in the middle of a field by aliens,” he wrote in the Boston Globe, 70 years after his family’s part in Telkes’s experiment.

Eventually, however, the experiment began to fail. Glauber’s salt had a few problems: Over successive heating and cooling cycles, it stratified permanently into solid and liquid components, requiring the bins to be replaced. The salt was also corrosive, and began to leak from its metal containers. Midway through the home’s third winter, the heating system broke down.

For Telkes, however, perfection was never the point. She understood the necessity of exciting the public imagination about the possibilities of solar power. “Each new house,” she explained in 1950, “is another experimental stepping stone toward the use of the sun as a fuel resource.” Before the adoption of a new technology, people needed to be sold on its value—its glamour, even. If cutting a fashionable figure in front of the Sun House quickened support of solar energy, she would play to the camera.

When Ralph Morse first set out to become a photographer, one of his first jobs was at Harper’s Bazaar magazine. After only three days, though, he quit—according to his 2015 New York Times obituary, “he found fashion shoots vapid.” The image he captured of Mária Telkes could just as easily have appeared in Vogue as in LIFE, but in this case Morse’s subject satisfied his need for substance. Mária Telkes wanted nothing less than to transform the way society got the power it needed to thrive. “It is the things supposed to be impossible that interest me,” she once said. “I like to do things they say cannot be done.”

At American Experience we're always coming across photos from the past that we can't stop thinking about—images that are worth a thousand words.

Since pre-colonial times, Americans' relationship to the natural world has shaped politics, policy, commerce, entertainment and culture. In this collection, delve into our complicated history with the environment through American Experience films exploring wide-ranging topics, from our struggles to exert dominion over nature to our attempts to understand and protect it.