The Marvelously Inventive Life of Mária Telkes

A look at the scientist’s breakthrough innovations, from the world’s first solar-heated home to an electricity-free Easy Bake Oven

Scientist Mária Telkes spent her life chasing the sun. Telkes, who was born in Hungary in 1900, first became interested in solar energy while studying at the University of Budapest. After receiving her doctorate in physical chemistry in 1924, she emigrated to the United States and began work as a biophysicist at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. In the late 1930s, Telkes studied energy conversion for Westinghouse Electric before joining the Solar Energy Conversion Project, a research unit at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in 1939.

Throughout her career, Telkes was a pragmatist who operated in the realm of applied science; she was interested in seeing her inventions put to use in the real world. By the time of her death in 1995 she had earned more than 20 patents, most of them for inventions that exploited what she saw as the limitless potential of solar power. “Sunlight will be used as a source of energy sooner or later anyway,” Telkes wrote in a 1951 paper, adding, “Why wait?”

Here are a few of her best-known creations, innovative evidence that the nickname bestowed upon her by the media—the Sun Queen—was well-earned.

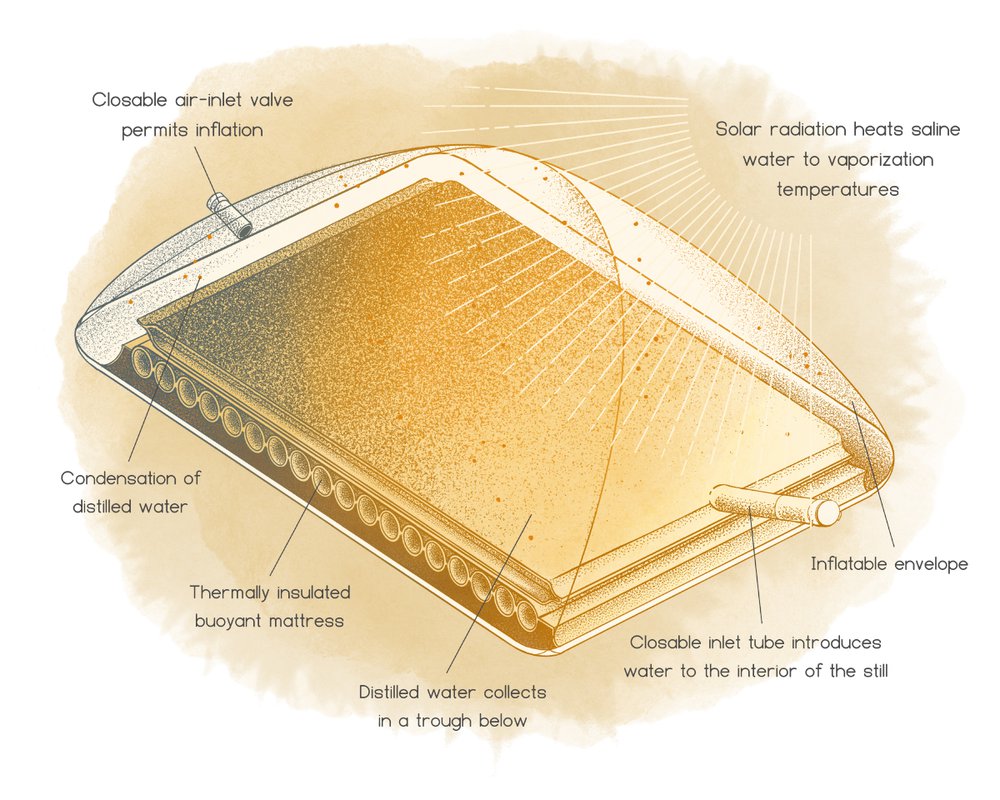

Solar Still: Lifesaving WW II Water Purifier

Telkes was at MIT when World War II broke out, and in 1941 she found herself temporarily reassigned to the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development, an ad hoc department created to assist with the war effort. Setting aside her own work on solar-powered heating systems, she was tasked with devising a solution to an urgent problem. Hundreds of American service members were being shot down in the Pacific theater each week, where, adrift in the ocean, they would die of dehydration. The U.S. government wanted a small, portable device that could turn saltwater into something drinkable. With her inflatable solar-powered desalination kit, Telkes provided an elegant, simple solution. The sun’s heat would shine through the kit’s balloon-like plastic film, evaporating the water inside; when the water condensed again, its salts were left behind, making the remaining water potable. Her solar still—for which she received a patent in 1968—would eventually become part of the military’s standard-issue emergency medical kit.

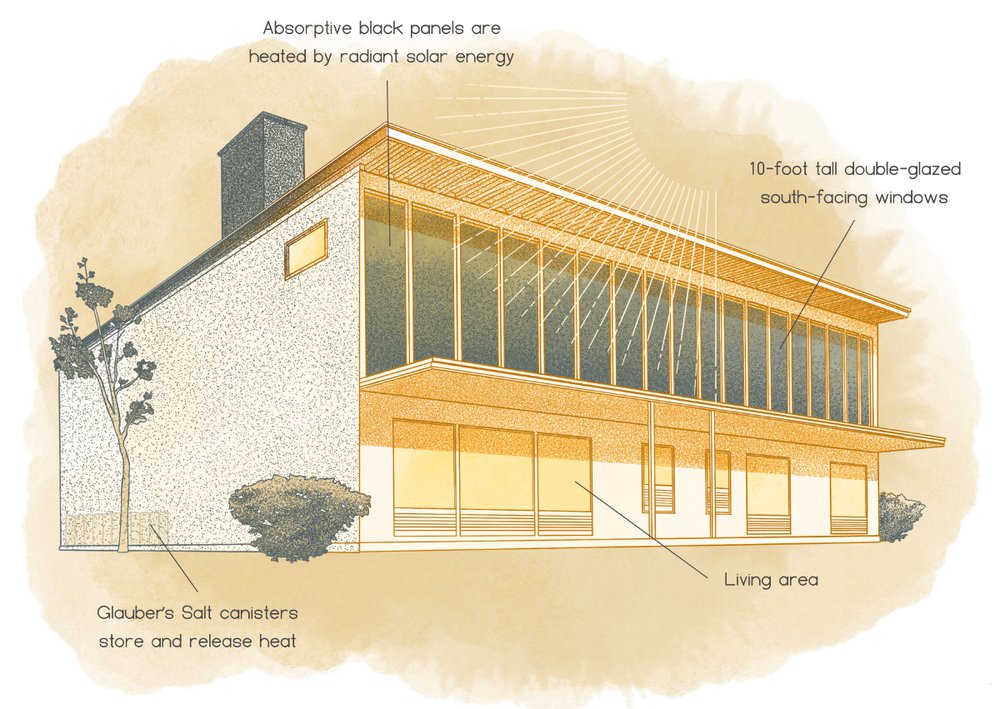

Dover Sun House: The World’s First House Heated Solely by the Sun

Most homes are places for people to live, but the Dover Sun House was more than that—it was Telkes’s grand experiment and the first completely solar-heated home. Constructed in 1948, her most famous project was a collaboration with architect Eleanor Raymond and patron Amelia Peabody. For years, Telkes had experimented with a substance called Glauber’s salt, the sodium salt form of sulfuric acid. Glauber’s salt was a phase-changing material, and depending on its temperature transformed from a solid to liquid, and back again. At 90° Fahrenheit, the sun’s rays melted the salt; when the salt cooled and resolidified, the solar energy trapped in its crystals was released and could then be used to heat the air circulating throughout the two-bedroom home. The Dover House’s 18 south-facing windows concealed 4,275 gallons of the salts which, for two and a half New England winters, silently and successfully kept its occupants warm.

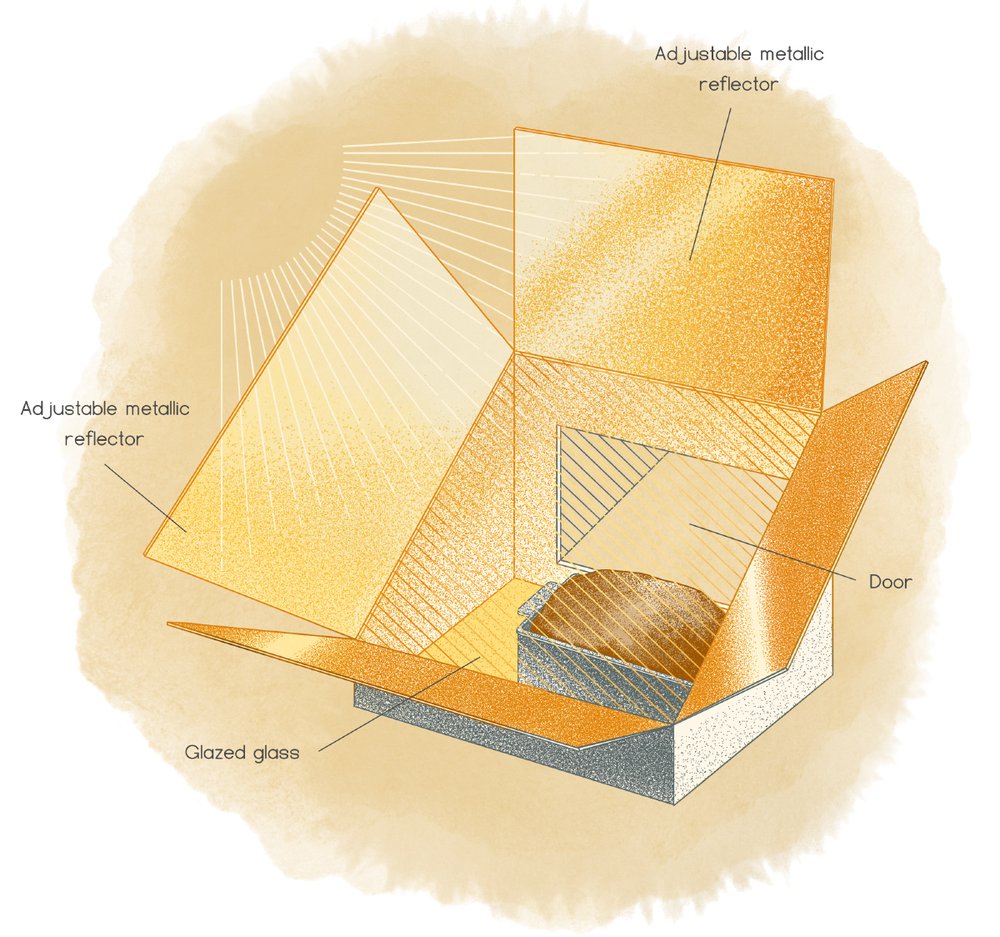

Solar Oven: An Electricity-Free Easy Bake Oven

In 1953, when Telkes was at New York University, she received a Ford Foundation grant to design and develop a solar stove for use in developing countries. Once again her design was ingeniously simple. The stove consisted of an insulated metal box with doors on either end, covered with glass above the area where food was placed. When the sun’s rays shone through the glass, they were amplified by four metal plates positioned at 60-degree angles; triangular mirrors between the plates further amplified solar wavelengths. The stove was capable of reaching temperatures of 400 degrees, required no special materials to construct, and cost only four dollars. Easy to use, the stove found a ready market in midcentury India, exactly the kind of tropical climate she had envisioned for her invention. Telkes extolled its virtues to a reporter during a cooking demonstration, saying, “Everything seems to taste so much better when it is cooked by the sun.”

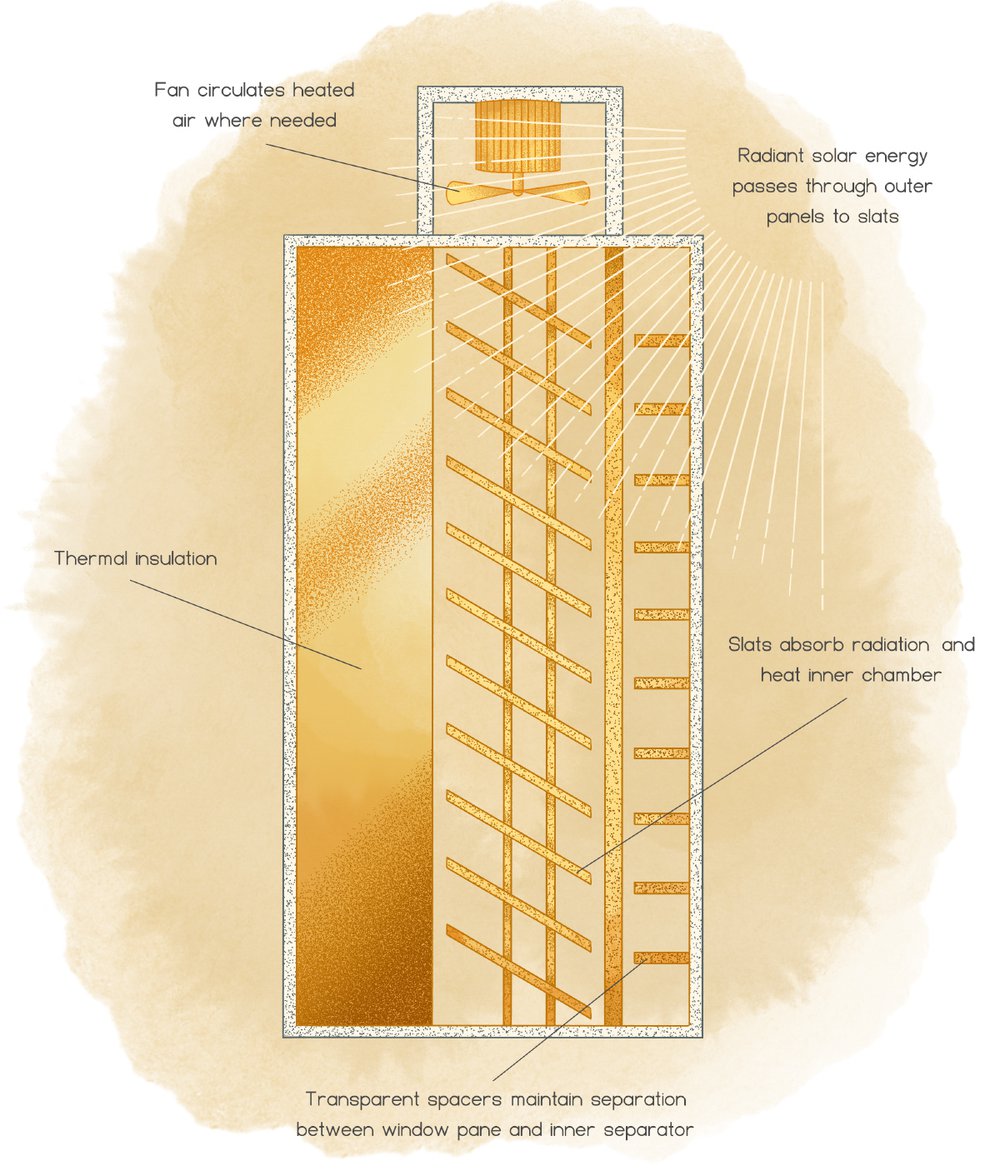

Solar Air Heater: A Temperature-Control Unit for All Seasons

In 1977, Telkes received a patent for an invention she created at the University of Delaware while continuing her work on solar home building projects. The design of her solar air heater had a column of aluminum slats, visually similar to venetian blinds, all held within a rectangular housing placed alongside a home. A transparent pane on one side of the slats allowed the sunlight through, and the slats could be positioned at varying angles depending on the angle of the sun at a home’s site. In the winter, they could be arranged to absorb maximum light; in the summer the slats would reflect light back outward. The absorbed solar energy heated the air within the rectangular housing, which could be directed through a home using a fan and air ducts. Insulated backing on the home-adjacent side of the slats’ housing isolated the hot air, keeping heat from uncontrollably transferring through the wall into a home. In Telkes’s deep practicality, the heater automatically adjusted its heat output during the year without any moving parts or maintenance required.

Since pre-colonial times, Americans' relationship to the natural world has shaped politics, policy, commerce, entertainment and culture. In this collection, delve into our complicated history with the environment through American Experience films exploring wide-ranging topics, from our struggles to exert dominion over nature to our attempts to understand and protect it.