Red Summer: When Racist Mobs Ruled

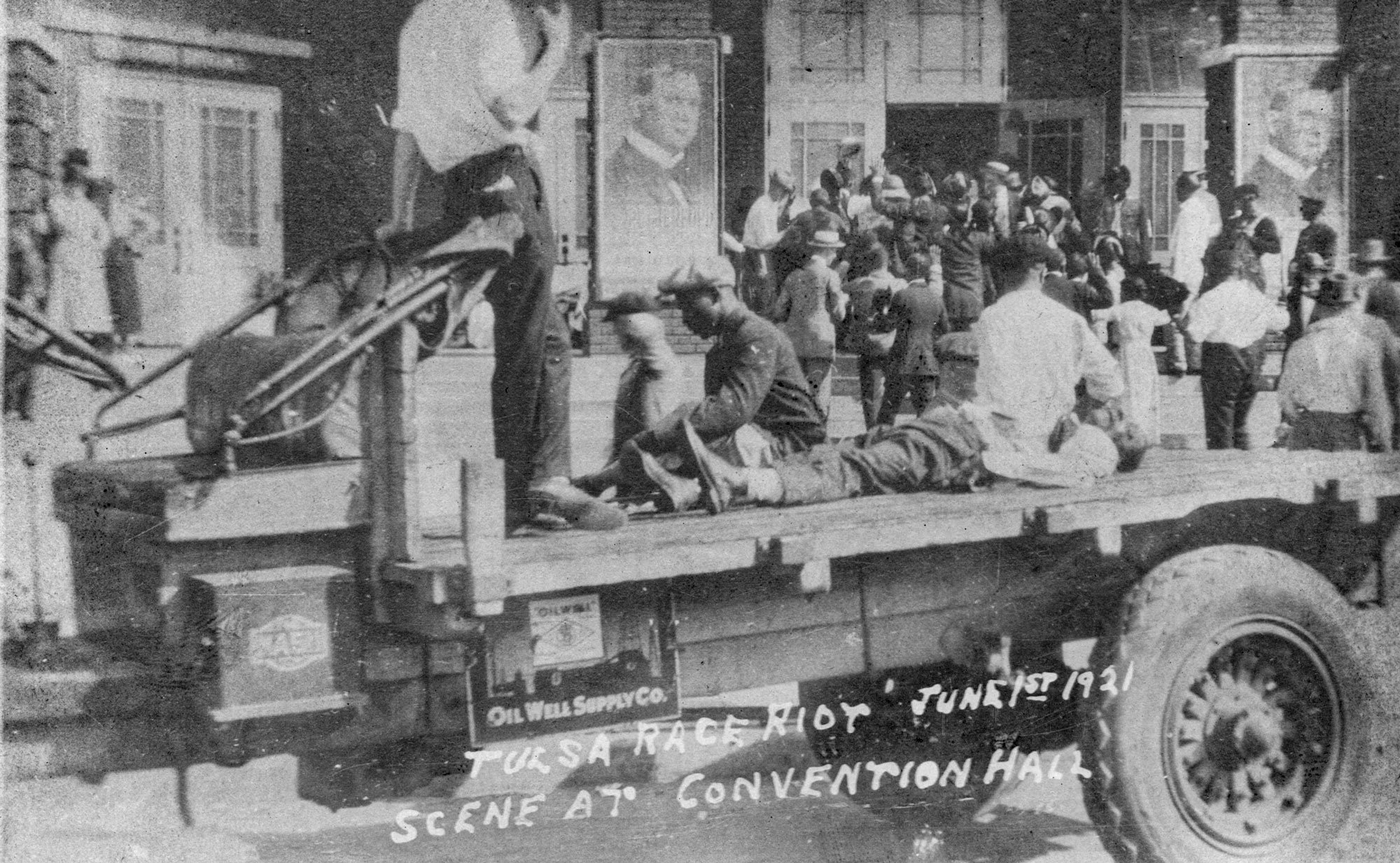

How a pandemic of racial terror led to the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

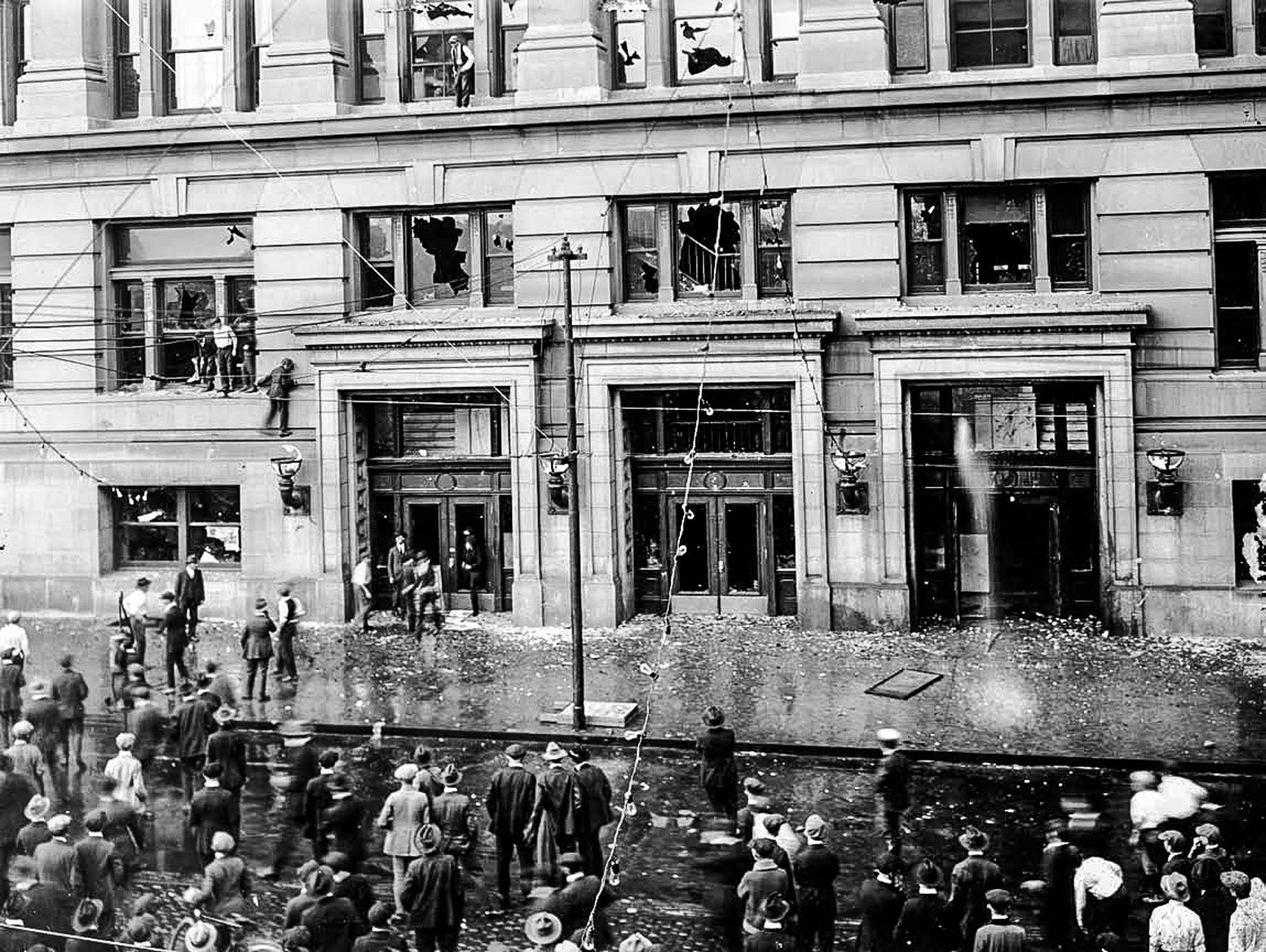

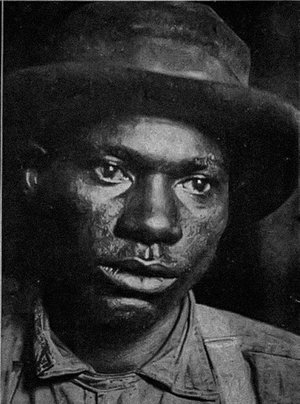

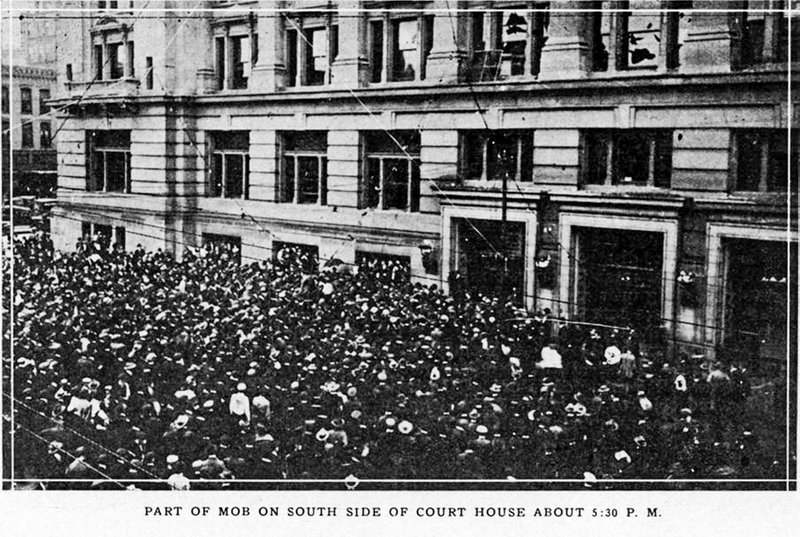

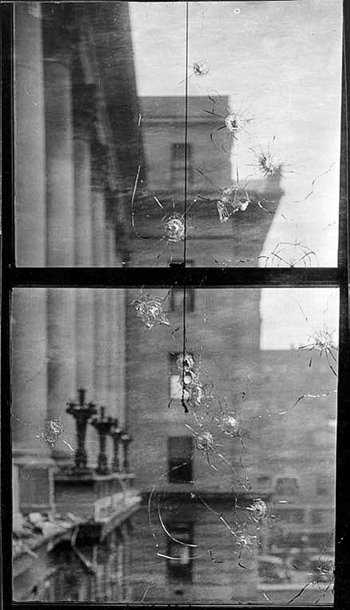

On September 27, 1919, a mob of at least 10,000 white people stormed the courthouse in Omaha, Nebraska, demanding the sheriff turn over Will Brown, a 40-year-old Black man. They raided the building, scaled walls and smashed windows. When the mob’s initial demands were refused, they set fire to the courthouse, turning it into a seething furnace. Omaha Mayor Ed Smith tried to intervene, but the mob tried to lynch him. Smith escaped badly injured.

From inside the courthouse, terrified white inmates threw down a note surrendering to the mob: “THE JUDGE SAYS HE WILL GIVE UP NEGRO. BROWN. HE IS IN THE DUNGEON. THERE ARE TEN WHITE PRISONERS ON THE ROOF. SAVE THEM.”

The frenzied horde finally broke into the jail and dragged Brown out. They tortured him, dismembered him, tied a rope around his neck and hoisted him up on a pole on the south side of the courthouse. As his body dangled in agony, they shot him more than 100 times. After they were sure he was dead, they sliced the rope and Brown’s body dropped to the pavement. Then the frenzied mob, which the local newspaper referred to as a “lynching committee,” cursed, kicked and spat on the body of the Black man.

Still, the mob of thousands of white men and women was not finished with the lynching. Someone found a new three-quarters-inch rope and tied Brown’s body to a car. Then they dragged his corpse slowly through the crowd, over glass and stones, through the streets to the edge of Omaha’s Black neighborhood, as a symbol of their rage. There, the “lynching committee” poured kerosene on Will Brown.

And lit his body with fire.

As they witnessed burning flesh, hundreds of the well-dressed men stood back and grinned.

They watched the contorted body of Brown, a 40-year-old innocent meatpacker, burn. A newspaper photographer snapped a photo of the petrified corpse, capturing one of the most horrific photos of racial lynching in U.S. history.

That night, the horde “also murdered at least one other African American who was walking on the streets and caught by the throng,” according to North Omaha History. The rioters “wounded at least 20 policemen; and demolished at least 10 homes in the Near North Side neighborhood.”

That year, Omaha would become one of at least 26 cities across the country where barbaric white mobs attacked Black people and Black communities during a reign of racial terror that author James Weldon Johnson labeled “Red Summer.”

The massacres and lynchings that occurred during “Red Summer,” a term used to describe the blood that flowed in the streets of America, were sparked by disparate events, but the common denominator was racial hatred against a people who had recently risen out of enslavement and prospered. In Omaha, Will Brown was falsely accused of assaulting a white woman as she walked with her boyfriend. In East St. Louis, it was Black men working factory jobs that white people wanted for themselves. In Longview, Texas, it was a Black man writing a newspaper story about a love affair between a Black man and a white woman. In Washington, D.C., it was an accusation that Black men tried to take a white woman’s umbrella. In Chicago, it was a Black teenager swimming in Lake Michigan and accidently floating over an invisible color line. In Elaine, Arkansas, it was Black sharecroppers trying to get better payment for their cotton crops. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, it was a Black teenager allegedly bumping into a white woman on an elevator.

During “Red Summer,” thousands of Black people were fatally shot, lynched and burned alive. Hundreds of Black-owned businesses and homes in Black communities were obliterated in fires fueled by racism and hatred. Millions of dollars of Black businesses and generational wealth were stolen.

Some historians claim that the racial terror connected with “Red Summer” began as early as 1917 during the bloody massacre that occurred in East St. Louis, Illinois, a barbaric pogrom that would eventually set the stage for the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, one of the worst episodes of post-Civil War racial violence ever committed against Black Americans. The Tulsa Massacre left as many as 300 Black people dead and destroyed more than 35 square blocks of Greenwood, an all-Black community so wealthy, the philosopher Booker T. Washington called it “Negro Wall Street.”

Survivors of the Tulsa Massacre witnessed white men and women descending on Greenwood, killing Black people indiscriminately in what appeared to be ethnic cleansing. Occupied houses of Black people were set on fire. When the occupants ran out, members of the white mob shot them. Elderly Black people were shot as they kneeled in prayer. Black women and children were killed in the streets. Black men, with their hands held up in surrender, were shot dead by whites.

Survivors reported that bodies of Black people were thrown into the Arkansas River, loaded on flatbeds of trucks and dumped into mass graves. In October 2019, the City of Tulsa re-opened an investigation into the search for mass graves. A year later, teams of archeologists and forensic anthropologists found a mass grave in the city-owned cemetery, which could be connected to the massacre. This spring, the City of Tulsa plans to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the massacre, as descendants of survivors demand reparations for what was lost, and protest against current oppression and racism.

Results of Red Summer

Nearly a century after the Tulsa Race Massacre, the country would again see another white mob attack. On January 6, 2021, pro-Trump supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol. People watched in shock as insurrectionists scaled the Capitol building, encouraged by the 45th president of the United States. The insurgents—including military veterans, police officers and elected officials—broke through police barricades and poured into the Capitol rotunda. They walked through the labyrinth of the Capitol hunting for members of Congress and threatening to kill then-Vice President Mike Pence and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

“It is just the beginning,” said Kevin Seefried, a white man from Wilmington, Delaware, carrying a Confederate flag into the Capitol.

Historians say that in order to understand the country’s racial divide and the attack on the Capitol, one must understand the racial tensions that led to “Red Summer.” “What we are facing within the racial tension that revealed itself in 2020, coupled with the pandemic, is sadly, ironically and tragically the result of what happened 100 years ago during ‘Red Summer,’ when there was a slew of race riots in American cities,” said Christopher Haley, a historian, writer, filmmaker and producer of the movie Unmarked: African American Cemeteries.

“Many of these riots erupted from tensions expressed between Blacks and whites over Black people’s growing economic and social status.”

Haley said there is a correlation between the Jan. 6, 2021 storming of the U.S. Capitol and the events that led to Red Summer. “I think the correlation is that the people rioting were white supremacists, Nazis or anti-Semitic. They carried Confederate flags. That certainly links itself to those persons during Red Summer who hated the progress of African Americans and politicians. It would be stretching it to say there is no correlation.”

White Backlash

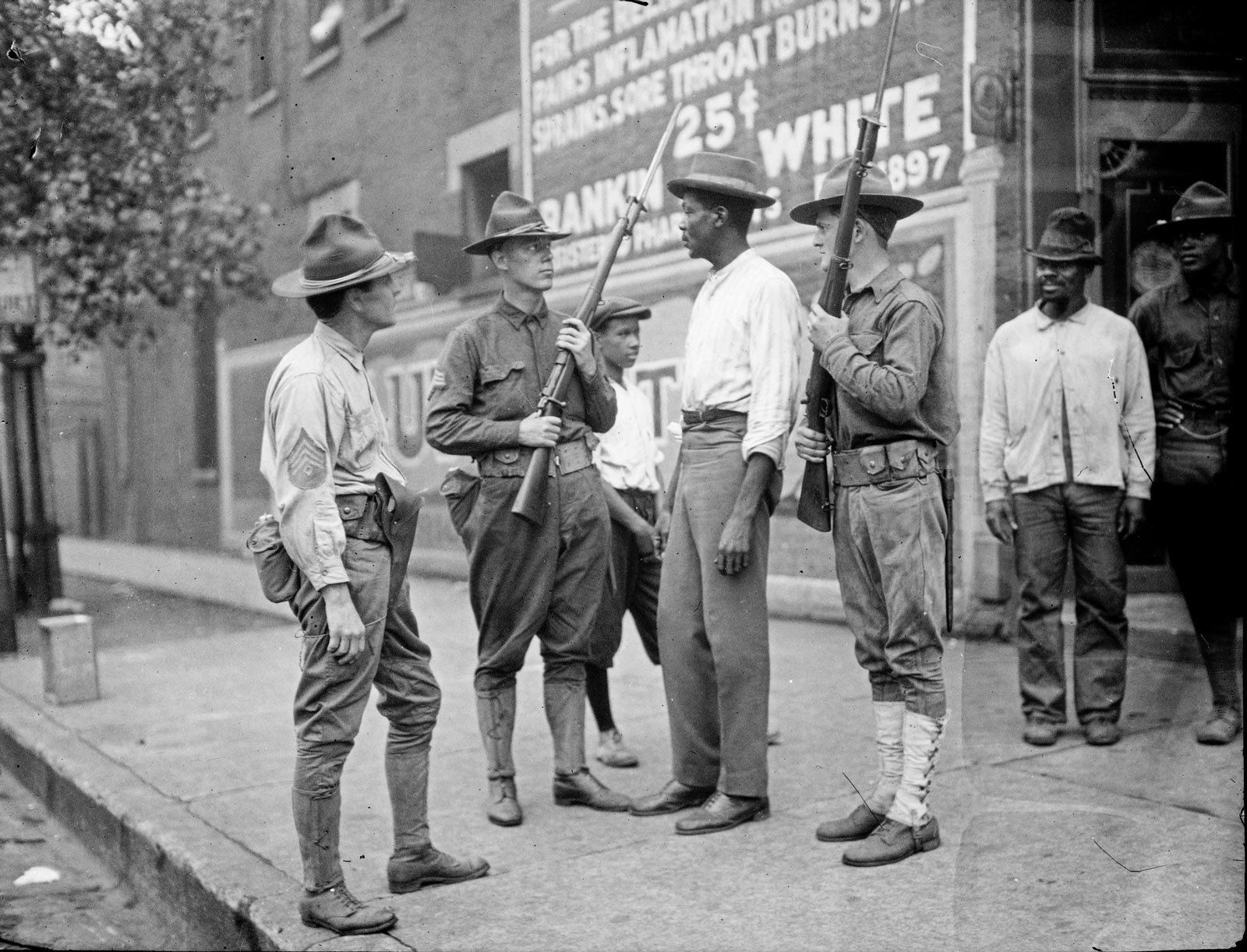

Red Summer’s reign of racial terror coincided with the end of World War I, an economic recession and the rising of the “New Negro,” Black people with a determined defiance, no longer willing to subjugate themselves to racism. Black veterans who had fought for democracy abroad in Europe returned to the United States demanding the country’s constitutional promise of equality.

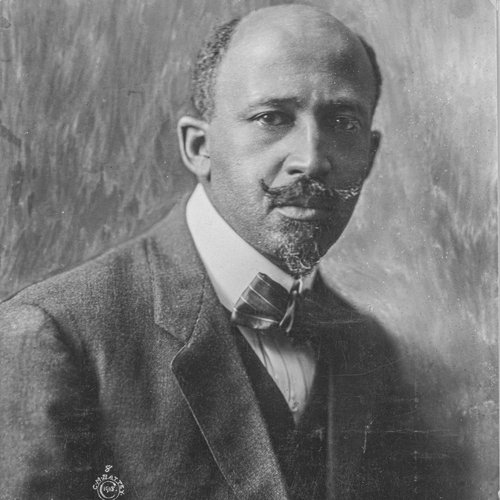

Black intellectuals, writers and scholars encouraged these veterans to fight against injustice, disenfranchisement and lynchings in the United States. “But by the God of heaven,” W.E.B. Du Bois, cofounder of the NAACP and author of The Souls of Black Folk, wrote in the Crisis Magazine, “we are cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land. We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting.”

“Make way for Democracy,” Du Bois added. “We saved it in France, and by the Great Jehovah, we will save it in the United States, or know the reason why.”

Longview, Texas

One of the first recorded racial conflicts of Red Summer began in Texas in May 1919. “Comparatively few people know of the race riot which was a precursor of the more serious outbreaks in Washington, Chicago and Knoxville,” the NAACP’s Crisis Magazine reported in 1919. “Last June, at Longview, in the state of Texas of ill-fame, a colored man, Lemuel Walters, was arrested and jailed on the charge of having been found in a white woman’s room.”

Samuel L. Jones, a professor and local leader, stopped at the jail where Walters had been detained. Jones, who was delivering The Chicago Defender, one of the country’s most prominent Black-owned newspapers, was told by three Black inmates and one white inmate that Walters had been taken from the jail by a gang of white men.

Days later, the local white-owned newspaper, The Longview Leader, reported that an unidentified Black man had been found fatally shot near the railroad. Professor Jones began asking questions about what may have happened to Walters. The inmates who had earlier told Jones that a gang of whites had taken Walters away were disappeared.

“At this point The Chicago Defender stepped in and on July 5 published a statement that the white woman whose name had been originally connected with Walters was really in love with him, would have been glad to become his wife and was deeply stricken by his death,” according to a 1919 Crisis Magazine article, explaining what The Chicago Defender reported. “The Defender also declared that the sheriff had seen the mob pass into the jail and was, therefore, an accessory before the fact.” The Defender accused the sheriff of releasing Walters to the white mob, which murdered him on June 17, 1919.

The accusations of the love affair printed in the Defender angered some of the local white men in Texas. Five days after the Defender story, Professor Jones was attacked, “horribly beaten, struck and cut over the head with a wrench and otherwise badly injured,” The Crisis reported in 1919. “Even then, he defended himself and managed to break away from his assailants—three white men—but he tripped, fell headlong and while still on the ground was beaten even more violently.”

Professor Jones was told that he was attacked because of the statement published in the Defender. He denied that he was responsible, then broke away from his attackers and ran.

The local sheriff sent word that Professor Jones “would be lynched before midnight unless he had already left town,” The Crisis reported in 1919.

On the morning of July 11, 1919, a white gang drove to Jones’s house, according to the Texas State Historical Association. “Four white men mounted the back porch and called for Jones to come out,” according to The Crisis. Someone fired at the larger group of white men in the yard. “In the violent scrimmage which followed, no colored men were killed, but it is reported that the manager of the Kelly Plow Works admitted the death of eleven white men,” The Crisis reported.

The whites withdrew. But at daybreak, they gathered again. “This time arson was the weapon,” setting fire to the house of Calvin Davis, a Black doctor, according to The Crisis. The mob also burned the homes of other Black people. “Professor Jones’ house – from which he had already escaped – and that of Dr. Davis was burned to the ground. The family of Dr. Davis was permitted to escape. But an innocent householder and his wife who lived opposite Professor Jones lost not only their house, but were themselves shot and seriously injured.”

The white mob burned the houses in the Black neighborhoods. In their rage they would establish a pattern followed by other white mobs in Black communities across the country.

In each community, the racial violence was often prompted by a false accusation that a Black man had assaulted a white woman. “That was all that needed to be said,” L.C. Menyweather-Woods, a professor in the Department of Black Studies at the University of Nebraska, said in the documentary "The Race Riot of 1919 in Omaha: The Lynching of Will Brown."

Fanning the Flames

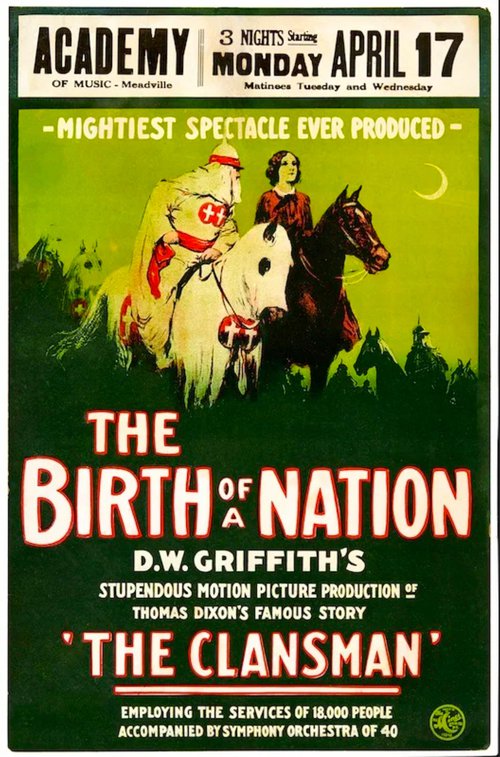

The spark for such false accusations could be traced back to the movie Birth of a Nation, a racist blockbuster by D.W. Griffiths, which was inspired by the novel The Clansman. The 1915 classic portrayed a racist and stereotypical portrait of Black people, while glorifying the brutality of the Ku Klux Klan. The movie depicted the Klan as the protector for the South and of white women during the Reconstruction period after the Civil War. But, in reality, the Klan was a terrorist organization that murdered thousands of Black people and raped and assaulted Black women.

Still, President Woodrow Wilson, who held a special screening of the movie at the White House, was said to have raved, “It is like writing history with lightning,” after seeing the film.

The film also prompted a reemergence of the Klan. After the film’s release, hordes of white people poured into the streets of some major U.S. cities, openly assaulting Black people. A white man in Indiana killed a Black teenager after watching the movie.

Racial lynchings of Black men, women and children increased during this period, which historians called the “Nadir”—a dark, low period in history. Hundreds of Black people were lynched, their tortured bodies dangling from trees.

“Strange Fruit,” sang Billie Holiday, the jazz singer who grew up during this period.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the Poplar trees.Pastoral scene of the gallant South

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of the magnolia sweet and fresh

Slowly, the jazz singer sang, “Then the sudden smell of burning flesh.”

The beauty in her face seemed to recede, as she sang in a tone echoing the agony of lynching victims. During her performances, audiences could hear a pin drop. Holiday slowed the song, enunciating each word, painting a vivid picture of lynchings and making white audiences twist in discomfort.

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot for the tree to drop

She would tilt her head back and wail—her voice crescendoing, the lyrics a haunting echo.

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

No Escape

It was that “bitter crop,” dangling during “Red Summer” that fueled “The Great Migration,” the journey of millions of Black people escaping racial terror in the South. They walked, caught trains and buses heading to cities in the North where many found more disappointment and a different kind of racism. They found poverty, crowded housing, redlining, racial and economic tensions prompted by white people who viewed the Black migrants as a threat to their jobs.

“Historians would come to call it the Great Migration. It would become perhaps the biggest underreported story of the twentieth century. It was vast. It was leaderless. It crept along so many thousands of currents over so long a stretch of time as to be difficult for the press truly to capture while it was under way,” author Isabel Wilkerson wrote in The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration.

“Over the course of six decades, some six million black southerners left the land of their forefathers and fanned out across the country for an uncertain existence in nearly every other corner of America. The Great Migration would become a turning point in history. It would transform urban America and recast the social and political order of every city it touched.”

As they fled, the racial terror tagged behind. For some, racial terror met them in the North with a seething animosity.

“The blood lust which World War I was too short to satiate made the year 1919 one of almost unmitigated horror,” Walter White, a field secretary for the NAACP, wrote in his autobiography, A Man Called White.

White, a Black man who looked white—with blond hair and blue eyes—became one of the most fearless and tenacious race investigators in history. In 1919, the NAACP sent White to Chicago to investigate the race riot there.

The Chicago Race Riot of 1919

The racial violence in Chicago began on Sunday, July 27, 1919, one of the hottest days in that city’s history. Eugene Williams, a Black teenager, walked to South Side Beach. Eugene, who was 17 at the time, put his make-shift raft into Lake Michigan and began floating in the cool waters.

As he waded, Eugene’s raft mistakenly crossed an invisible color line drawn in the waters of Lake Michigan. Suddenly, a white man trying to protect that invisible color line, began to throw stones at the Black teenager.

The barrage of stones hit Eugene, knocking him off his raft. Eugene fell, sinking into the cold waters. The Black teenager drowned.

His murder would spark one of the worst episodes of racial violence in the city’s history, setting off seven days of clashes. White people climbed into cars and raced through the Black Belt of the city, shooting at Black people, burning and looting Black people’s homes.

“After seven days of shootings, arson and beatings, the Race Riot resulted in the deaths of 15 whites and 23 blacks with an additional 537 injured (195 white, 342 black),” according to the Chicago History Museum. “Since then, a century of African American activism has challenged the racism and social hypocrisy that allowed those responsible for Eugene Williams’s death to elude justice.”

The NAACP investigator Walter White concluded: “The Chicago riot taught me that there could be as much peril in a Northern city when the mob is loose as in a Southern town such as Estill Springs. I was constantly made aware in white areas, especially the Halsted Street area near the stockyards, that eternal alertness was the price of an uncracked skull. I naively believed that I was well enough known in Negro Chicago, despite my white skin, to wander about at will without danger. This fallacy nearly cost me my life.”

As bad as the riot was in Chicago, White would discover that a more violent massacre would occur only weeks later. It would erupt after Black sharecroppers planning to form a union to fight for better crop wages and escape a system of Southern peonage were killed in the muddy fields of rural Arkansas.

“The bloody summer of 1919 was climaxed by an explosion of violence in Phillips County, Arkansas, growing out of the sharecropping system of the South. The incident was fated to affect materially the legal rights of both Negro and white Americans,” White wrote. “Throughout the nation newspapers published alarming stories of Negroes plotting to massacre whites and take over the government of the state. The vicious conspiracy, so the stories ran, had been nipped in the bud, but it had been necessary to kill a number of ‘black revolutionists’ to restore law and order.”

Walter White took the first train South, heading from Chicago for Arkansas.

Elaine, Arkansas

The massacre in Elaine, Arkansas, began on the night of September 30, 1919, when white men fired on a church in Hoop Spur, Arkansas. Inside the church, Black men, women and children had gathered to discuss forming a union to address the peonage debt spiral created by white landowners, who continued to cheat Black farmers out of profits from growing cotton.

Inside the church, the Progressive Farmers and Household Union met. Black veterans inside the church returned fire, killing a white man.

And again, all hell broke loose. Rumors spread that the Black people were rising up in Hoop Spur. Thousands of white rioters from as far away as Mississippi, Tennessee, Texas and Louisiana descended on the rural Black community in Phillips County, hunting and killing hundreds of Black people.

“The press dispatches of October 1, 1919, heralded the news that another race riot had taken place the night before in Elaine, Ark., and that it was started by negroes who had killed some white officers in an altercation,” Ida B. Wells-Barnett wrote in her book The Arkansas Race Riot.

Some historians believe as many as 800 Black people may have been killed in Elaine.

“Later on, the country was told that the white people of Phillips County had risen against the Negroes who started this riot and had killed many of them,” wrote Wells-Barnett, “and that this orgy of bloodshed was not stopped until United States soldiers from Camp Pike had been sent to the scene of the trouble.”

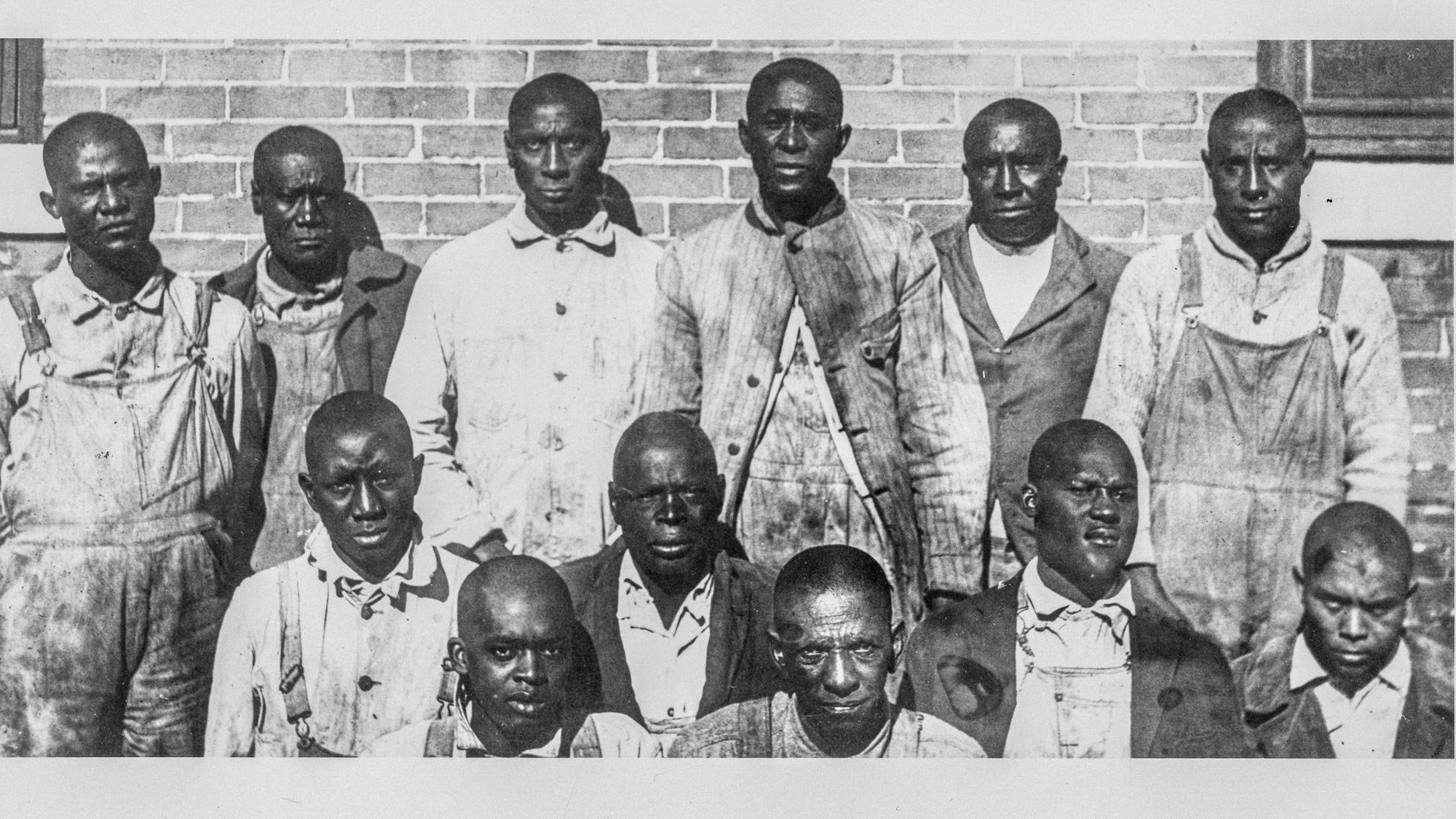

More than 285 Black people were arrested in Elaine and surrounding areas.

The men were taken to court in Helena, Arkansas, chained and forbidden to meet with an attorney. At least 12 of the Black men arrested were tortured and beaten, according to records. The white jailers soaked rags with formaldehyde and pushed them into their noses. They also used electrical shocks against the Black men’s genitals to try to coerce confessions for starting the massacre. After a six-minute trial, 12 Black men were sentenced to die in the electric chair. Seventy-five Black people were sent to prison on sentences from 5 to 21 years.

The Chicago Defender published a letter by Wells-Barnett appealing to Black people across the country to raise money for the Black men condemned to death row in Arkansas.

One of the Black men in jail wrote to Wells-Barnett, thanking her for her help. “We are innercent [sic] men,” he wrote. “We was not handled with justice at all Phillips county Court. It is prejudice that the white people had agence we Negroes. So I thank God that thro you, our Negroes are looking into this trouble, and thank the city of Chicago for what it did to start things and hope to hear from you all soon.”

Moved by the letter, Wells-Barnett took the train to Arkansas, where she talked with some of the wives of the 12 condemned. Then Wells-Barnett, a fearless anti-lynching crusader and journalist, slipped into the jail and spent the day interviewing the Black men.

“They had been beaten many times and left for dead while there, given electric shocks, suffocated with drugs and suffered every cruelty and torment at the hands of their jailers to make them confess to a conspiracy to kill white people,” Wells wrote. “Besides this a mob from outside tried to lynch them.”

After the NAACP took the case, the fate of the men, who became known as the “Elaine Twelve,” made national news. NAACP attorney Scipio Jones took their case to the U.S. Supreme Court and ultimately won their release off of death row.

The Tulsa Race Massacre

The bloody reign of racial terror did not end in Arkansas, nor did the horrible season called “Red Summer” end in 1919. In its aftermath, white mobs continued to mobilize, fueled by incomprehensible hatred of Black people, and determined to destroy Black social and economic progress.

In 1921, in Tulsa, that hatred would erupt into one of the worst racial massacres against Black people in U.S. history, following the pattern of the “Red Summer” massacres.

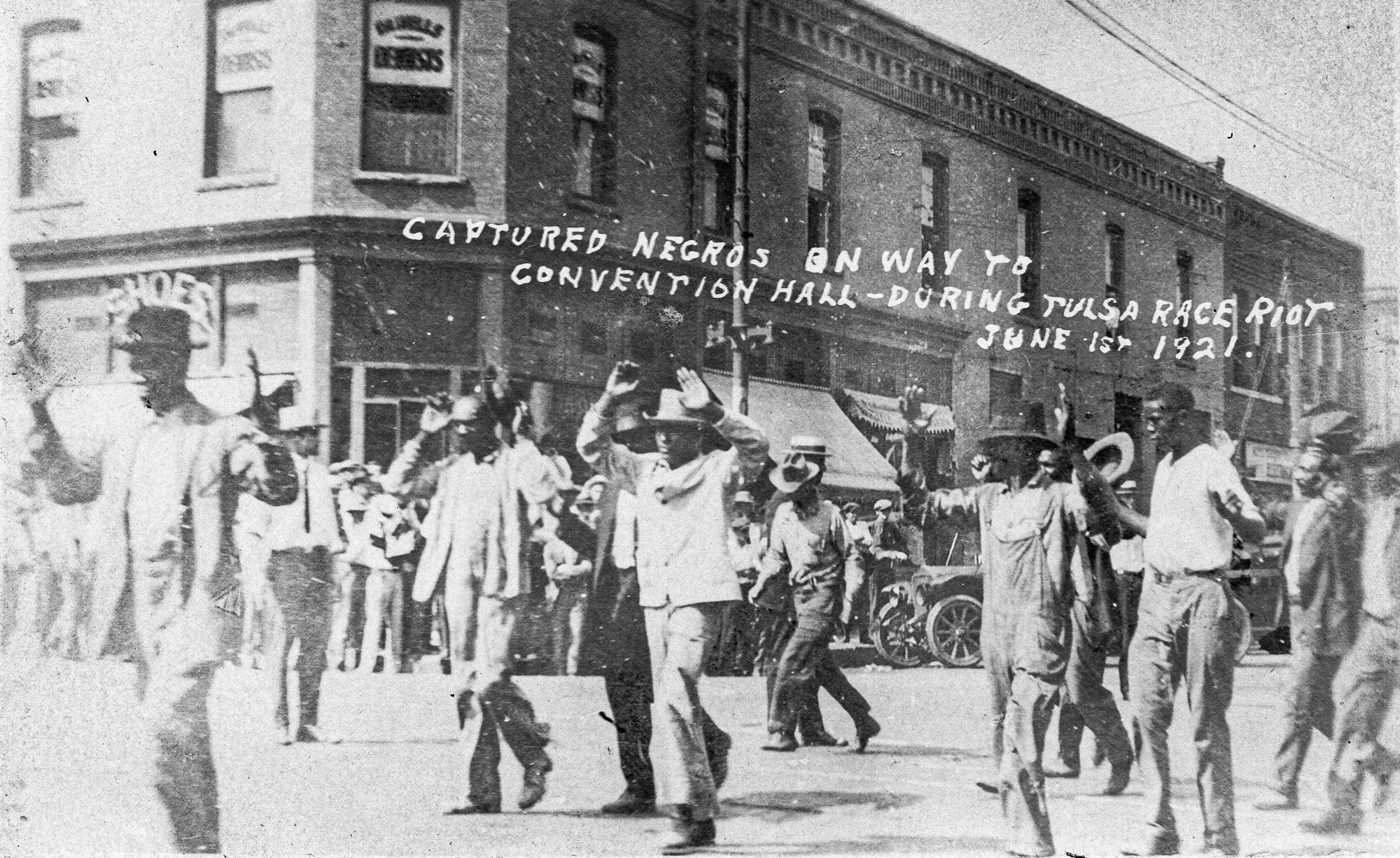

On May 30, 1921, a Black teenager who went by the name “Diamond” Dick Rowland went to the Drexel Building in downtown Tulsa, the only building in the area that allowed Black people to use the restroom. Rowland, according to historical accounts, stepped on an elevator operated by a young white woman named Sarah Page. When the elevator doors opened on the third floor, she screamed. Rowland ran. Historians believe that Rowland may have bumped into Page, stepped on her foot or tripped.

Rowland, who lived in Greenwood, the Black section of North Tulsa, was later arrested and charged with assaulting a white woman.

The Tulsa Tribune published a story calling for the lynching of Rowland. “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator,” blared the headline published on May 31, 1921.

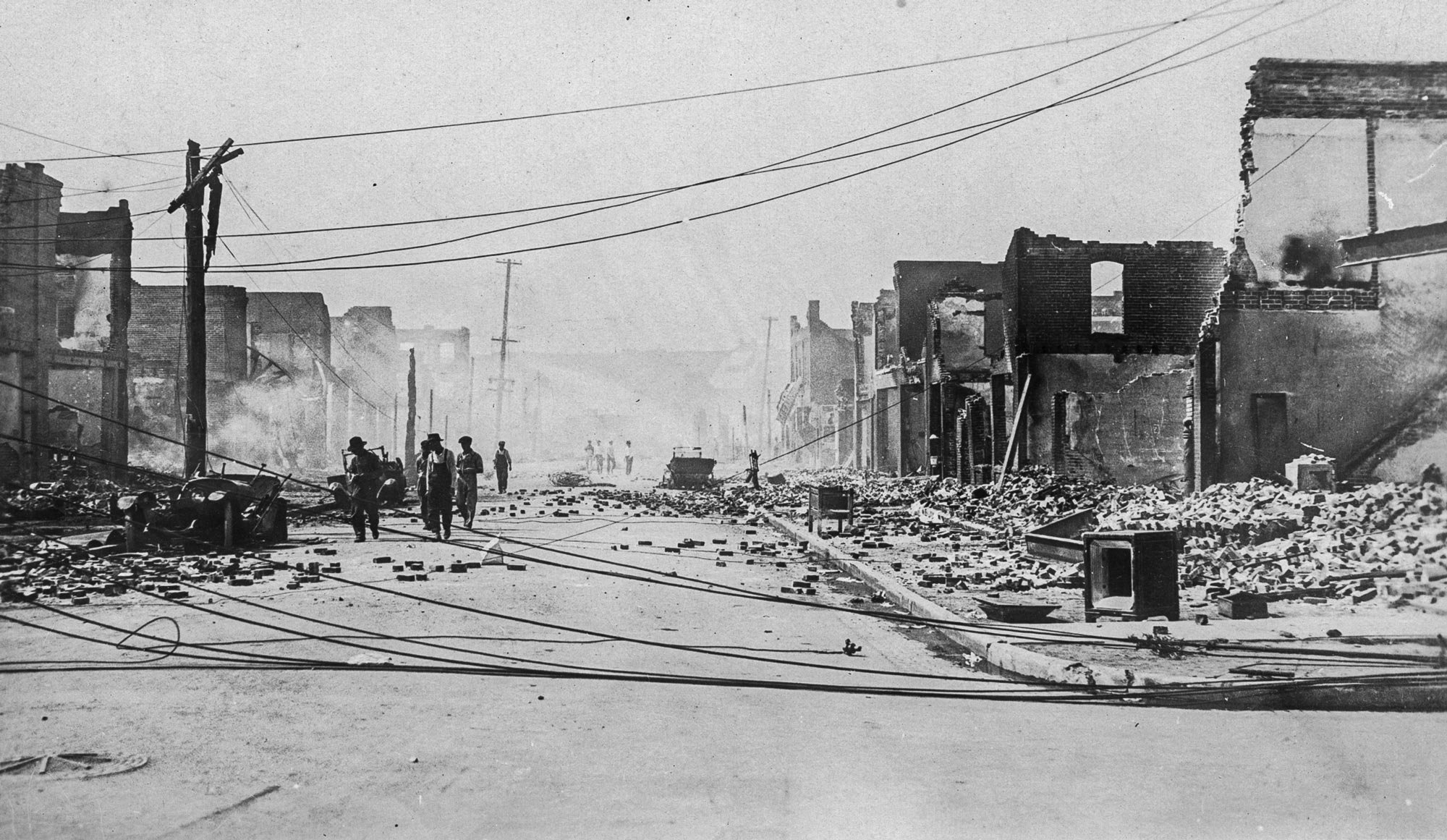

A white mob answered the call and began amassing at the county courthouse. The attack on the Black community of Greenwood lasted 48 hours. When it was over, the city took surviving Black people to makeshift concentration camps. More than 1,200 businesses were destroyed, including a Black hospital, school, library, theatres, and savings and loans. The frenzied throng of white people burned churches.

“At best, Tulsa Police took no action to prevent the massacre,” Human Rights Watch concluded in a June 2021 report. “Reports indicate that some police actively participated in the violence and looting.”

White civilians were deputized by the city to shoot Black people. “Hundreds of whites they deputized, participated in the violence—at times providing firearms and ammunition to people, all of them white—who looted, killed and destroyed property,” according to Human Rights Watch. “No one was ever prosecuted or punished for the violent criminal acts.”

After the massacre, Black people went to the courthouse to file claims for their losses, which “amounted to tens of millions in today’s dollars,” the Human Rights Watch reported. “The massacre’s devastating toll, in terms of lives lost and harms in various ways, can never be fully repaired.”

After the massacre, city officials failed to help Greenwood rebuild and furthermore tried to keep Black people from rebuilding in Greenwood by implementing restrictive building codes. “Efforts to secure justice in the courts have failed due to the statute of limitations,” Human Rights Watch reported. “Ongoing racial segregation, discriminatory policies, and structural racism have left black Tulsans, particularly those living in North Tulsa, with a lower quality of life and fewer opportunities.”

As the city approaches the race massacre’s 100th anniversary, Human Rights Watch added support for reparations. “A movement is growing to urge state and local officials to do what should have been done a long time ago,” Human Rights Watch reported, “act to repair the harm, including by providing reparations to the survivors and their descendants and those feeling the impacts today.”

Governments are obligated to address human rights violations, Human Rights Watch reminded. “The fact that a government abdicated its responsibility nearly 100 years ago and continued to do so in subsequent years does not absolve it of that responsibility today—especially when failure to address the harm and related action and inaction results in further harm, as it has in Tulsa.”

Tulsa Lawsuit for Reparations

In September 2020, survivors of the massacre and their descendants filed a lawsuit seeking reparations and demanding the City of Tulsa “repair the damage” left in the legacy of the horrific massacre.

“The massacre was one of the most heinous acts of racial terrorism committed in the U.S. by those in power against Black people since slavery,” said Damario Solomon Simmons, a Tulsa lawyer and one of the lead attorneys working on the lawsuit. “White elected and business leaders not only failed to repair the injuries they caused, they engaged in conduct to deepen the injury and block repair.”

The lawsuit identifies seven defendants who contributed to the “public nuisance” and “unjustly enriched themselves at the expense of the Black citizens of Tulsa and the survivors and descendants of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.”

The survivors claim that five of the defendants—the City of Tulsa; Tulsa County; the then-serving Sheriff of Tulsa County; the State National Guard, which is a branch of the Oklahoma Military Department; and Tulsa Regional Chamber, also known as the Chamber of Commerce—were responsible for the massacre.

The Race Massacre still troubles Tulsa nearly 100 years later, as Black people there continue to call for justice.

Not One Perpetrator Has Been Charged

Each week, before Wednesday night Bible study, the Rev. Robert Turner goes to Tulsa’s City Hall. In front of the teeming glass structure, which towers over the city, Turner raises a bullhorn and shouts, reminding people passing by that the city was the site of one of the most gruesome racial massacres in the U.S.

Turner is senior pastor of Vernon AME, which sits on the main street in Greenwood. The church was burned by white mobs during the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Black people fleeing the raging white mobs hid in the church’s basement, which is one of the few remaining original structures that survived the massacre.

“Black people were murdered in this city, killed by mass racial terror,” Turner shouts into a bullhorn. “Innocent lives were taken. Babies burned. Women burned. Mothers burned. Grandmothers burned. Grandfathers burned. Husbands burned. Houses burned. Schools burned. Hospitals burned. Our sanctuary burned. The blood of those you killed in Tulsa still cries out.”

White people walk by. The traffic pauses at the light. A small crowd gathers at the corner; some carry signs demanding reparations.

Turner, in a white straw hat, continues preaching: “These Black people asked for nothing from this city, state or country. These former veterans from World War I came here and wanted to live out the American dream.”

Turner cries out.

“Tulsa, how did you repay them? You, out of jealousy, out of racism, you went down to Greenwood and looted and killed innocent people and you dumped their bodies into mass graves.”

His voice rises.

“You know the first time bombs were dropped on American soil?” Turner demands. “The first time bombs were dropped on American soil was not during Pearl Harbor. The first time bombs were dropped on American soil was right here in Tulsa. You burned it to the ground and to this day, not one perpetrator has been charged with one crime.

“Until this day, the bodies of those who were slain are lying in unmarked graves.”

“You made laws to prevent them from building homes and businesses back. What kind of civilized society burns churches?”

Turner turns the bull horn to the building.

“The blood of those you killed, the blood of those you killed in cold blood, in broad daylight. Their blood is on your hands.”

DeNeen L. Brown has been an award-winning writer at The Washington Post for more than 35 years. Brown, who has written for the Metro, Magazine and Style sections, was also a Canada bureau chief for The Washington Post. As a foreign correspondent, she wrote dispatches from Greenland, Haiti, Nunavut and an icebreaker in the Northwest Passage. She is an associate professor of journalism at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland.

An AMERICAN EXPERIENCE collection featuring a selection of films documenting the African American Experience — along with articles, digital shorts and original features exploring America’s continued struggle with race, democracy and justice, and celebrating the contributions of Black Americans to the American story.