A Walk Along Black Wall Street

The Greenwood district in Tulsa, Oklahoma was once a Mecca for African American business. Then came the racist mob.

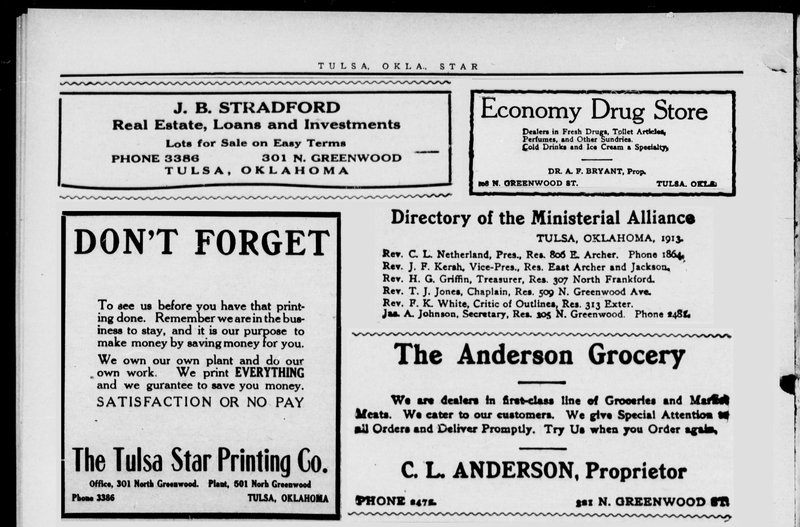

In early 1921, you could spend an entire day in the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma without once leaving its central thoroughfare, Greenwood Avenue. You might start with breakfast at Lilly Johnson’s Liberty Cafe before heading to Elliott & Hooker’s at 124 North Greenwood to buy a new suit or dress. If, say, the sleeves were too long, you could stop at H.L. Byar’s tailor shop across the street at 105 North Greenwood before picking up a prescription down the way at the Economy Drug Company. By then it was probably time for another meal, maybe a plate of barbecue eaten while perusing the pages of one of Greenwood’s two newspapers, the Tulsa Star or Oklahoma Sun. Playing pool at one of several billiard halls was an enjoyable afternoon pastime, or if glamour was more the order of the day, a photoshoot at A.S. Newkirk’s photography studio could be arranged. After dinner at Doc’s Beanery—the house specialty, smothered steak with rice and brown gravy—you could take in a silent film accompanied by live piano at the 750-seat Dreamland Theatre. Finally, a long and satisfying day would come to a close at 301 North Greenwood, when your head came to rest on a well-fluffed pillow in one of the Stradford Hotel’s 54 rooms.

Tulsa’s Greenwood district in early 1921 occupied about 40 square blocks of real estate in the city’s northwest corner. The district’s eponymous avenue ran for more than a mile through the community’s heart, the central artery of its livelihood and the place where inhabitants went to see each other and be seen. There and on adjacent streets, they also accessed the services of doctors (the district had 15), dentists, realtors and lawyers.

Probably the most remarkable thing about all of these entrepreneurs, professionals and their clients was that they were Black. The Stradford hotel, valued at $75,000 ($2.5 million in today’s dollars), was founded by J. B. Stradford, one of Greenwood’s architects and the son of a formerly enslaved man. By 1921, Stradford's real estate portfolio included the hotel, his own personal mansion, two dozen rooming and rental buildings, bathhouses, shoeshine parlors and pool halls. Stradford was also a highly public critic of Tulsa’s racial oppression. In a 1916 petition to the city, he lamented a segregationist zoning ordinance passed that year: “[S]uch a law is to cast a stigma upon the colored race in the eyes of the world,” he wrote, “and to sap the spirit of hope for justice before the law from the race itself.”

The Dreamland Theatre anchored Greenwood Avenue at its locus of activity, the intersection with Archer Street. The theater belonged to Loula Tom Williams, who with her husband John also owned an auto repair garage and a confectionary. The Williamses moved to Tulsa from Mississippi in 1903 in pursuit of the American dream, which they realized in their theater and other business interests. The couple owned Greenwood’s first car, a 1911 Norwalk with leather seats, that would cost more than $50,000 today. Loula’s first foray into entrepreneurship, the Williams Confectionary, was a popular site for marriage proposals, presumably celebrated with a shared ice cream sundae.

Greenwood was a mecca for Black-owned businesses, fulfilling its community’s every want and need. Booker T. Washington, after whom the district’s high school was named, called it “Negro Wall Street.” Students at the high school studied Latin, bookkeeping and physics and were prepared to attend college at the best schools in the country that would admit Black students.

Some of Greenwood’s residents were the descendents of enslaved African Americans who had accompanied Indigenous tribes from the southeast during Native American Removal. Many came from states in the former Confederate South in search of opportunity (Greenwood actually took its name from a town in Mississippi). And by 1921, around 11,000 people, more than five times the population of the district only a decade earlier, had made Greenwood home. That population explosion mirrored greater Tulsa’s, where the booming oil business supported a rapidly growing metropolis with its own proliferating commercial interests.

Jim Crow segregation ensured that the two economies, those of white and Black Tulsa, remained separate. As a result, the money someone spent in Greenwood stayed in the community, circulating and recirculating from one business to another, one proprietor to the next. Those entrepreneurs then reinvested their earnings into the district and helped to develop it further.

In its upward mobility, Greenwood was an archetypal American neighborhood of the early 20th century. But that mobility made it particularly vulnerable to the malignant forces of American racism, and as Greenwood’s borders expanded, so did white Tulsans’ jealousy and resentment.

On May 30, 1921, a young Black Greenwood resident was arrested for allegedly assaulting a white woman in a downtown elevator. Thwarted in their attempt to lynch him , white Tulsa invaded the district with murderous intent the next day. White mobs, some of them deputized by official arms of the government, looted, set fire to and destroyed businesses, churches, schools, a public library and a hospital. The Dreamland Theatre was torched, as was the Stradford hotel and both of Greenwood’s newspaper offices. More than 1,200 homes were demolished. A thriving, vital place was reduced, in less than 24 hours, to piles of smoldering ash and rubble.

By today’s estimations, the Tulsa Race Massacre left at least 300 dead, many more injured, and 10,000 homeless. Eighty years later, in 2001, Oklahoma published an official report that equated the atrocity to a pogrom: “[T]he city of Tulsa erupted into a firestorm of hatred and violence that is perhaps unequaled in the peacetime history of the United States.”

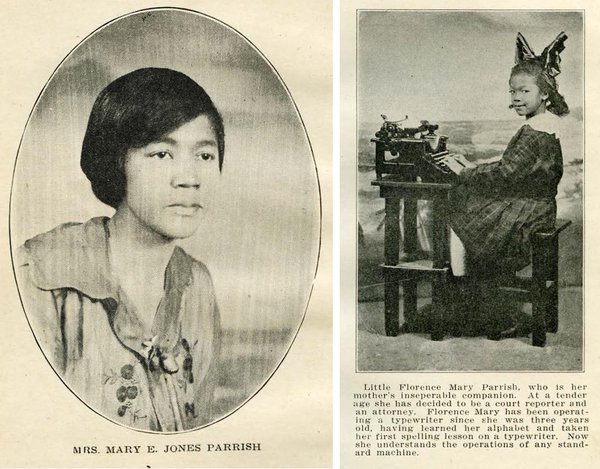

Accounts from the era confirm this assessment. During the massacre, pioneering journalist Mary E. Jones Parrish escaped the combat zone of Greenwood’s commercial district with her young daughter, dodging bullets to make it to relative safety. After interviewing eyewitnesses, gathering photographs of the decimation and assembling a record of property losses, Parrish authored one of the definitive contemporary reports of the atrocity, Events of the Tulsa Disaster.

Of her own personal experience of the massacre, Parrish wrote, “[s]omeone called to me to ‘Get out of that street with your child or you will both be killed.’ I felt it was suicide to remain in the building, for it would surely be destroyed and death in the street was preferred, for we expected to be shot down at any moment. So we placed our trust in God, our Heavenly Father, who seeth and knoweth all things, and ran out in Greenwood in the hope of reaching a friend’s home.”

Parrish also chronicled her community’s heroic efforts to rebuild what had been taken from them. They did so with next to no assistance. The $4 million in claims (more than $200 million in today’s dollars) filed by the massacre’s victims were all denied by insurers, who refused to make payments on damages incurred by what they deemed a riot.

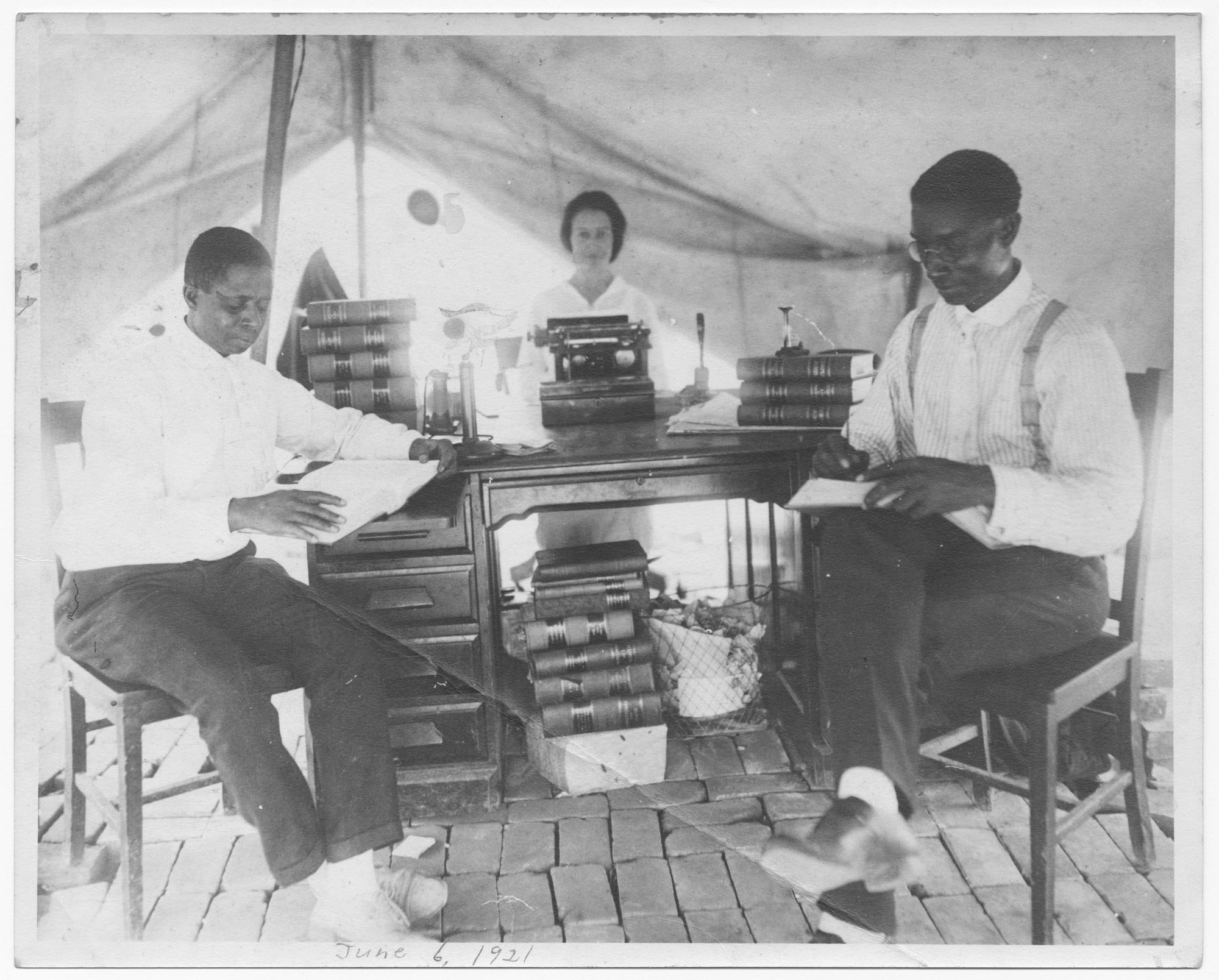

In fact, Oklahoma’s city and state officials tried to prohibit Greenwood’s residents from reestablishing their lives. White Tulsa’s political leadership and development interests passed fire ordinances intended to prevent the district’s reconstruction. Black residents found a stalwart advocate in Buck Colbert Franklin, a Greenwood attorney who worked out of a tent in the massacre’s immediate aftermath. Franklin represented community members in a case against the city in which the ordinances were eventually deemed a denial of inhabitants’ property rights.

By 1925, Greenwood stood again, rebuilt by its residents; their resilience was affirmed by the National Negro Business League’s selection of Tulsa as the site of its annual conference that year. White Tulsan’s racist attitudes toward African Americans remained, but Greenwood flourished nonetheless over the next several decades. The thirties and forties saw further economic development, and the community once again played host to high-profile out-of-town guests like Louis Armstrong and Nat King Cole.

Eventually, desegregation during the 1960s drew Tulsa’s African Americans beyond the district. As Greenwood’s residents spent their money elsewhere in the city, Tulsa planners hastened the neighborhood’s economic decline by using eminent domain to seize and demolish much of Greenwood’s commercial center. In 1960, for example, the city tore down the Dreamland Theatre building, which had become an Elks lodge and social center for the community. That destruction made way for Interstate 244 to cut directly through Greenwood Avenue and bisect the district’s central thoroughfare. Tulsa redlining and urban renewal policies hastened further deterioration. By 1980, Greenwood was largely a collection of deteriorating shuttered businesses and vacant homes.

In the last two decades, the area has been revitalized with new development. The benefits (and beneficiaries) of the recent economic growth remain controversial, however, with some community members arguing that gentrification further erases the area’s historic importance and public understanding of the massacre’s impact.

Now in 2021, a visit to the district might begin at 322 North Greenwood Avenue at the Greenwood Cultural Center, a nonprofit organization that fosters public awareness of Greenwood’s history. A memorial to Black Wall Street stands outside the center, yards from the Interstate 244 overpass. The marble slab was dedicated a generation ago on the massacre’s 75th anniversary and lists the hundreds of businesses once owned by African Americans in the district, among them the Dreamland Theatre and Stradford Hotel.

Above the columns of lost enterprise, a poem by massacre survivor Wynonia Murray Bailey is etched into the black stone. You might read the poem’s final stanza, accompanied by the sound of cars rushing by just 200 feet away:

Greenwood! Lest you go unheralded,

I sing a song of remembrance

While sons of your bounty, loyal still

Place a headstone at the site of your victory.

An AMERICAN EXPERIENCE collection featuring a selection of films documenting the African American Experience — along with articles, digital shorts and original features exploring America’s continued struggle with race, democracy and justice, and celebrating the contributions of Black Americans to the American story.