The Roots of American Islamophobia

Khomeini and the hostage crisis provided the United States with a new face and faith to fear.

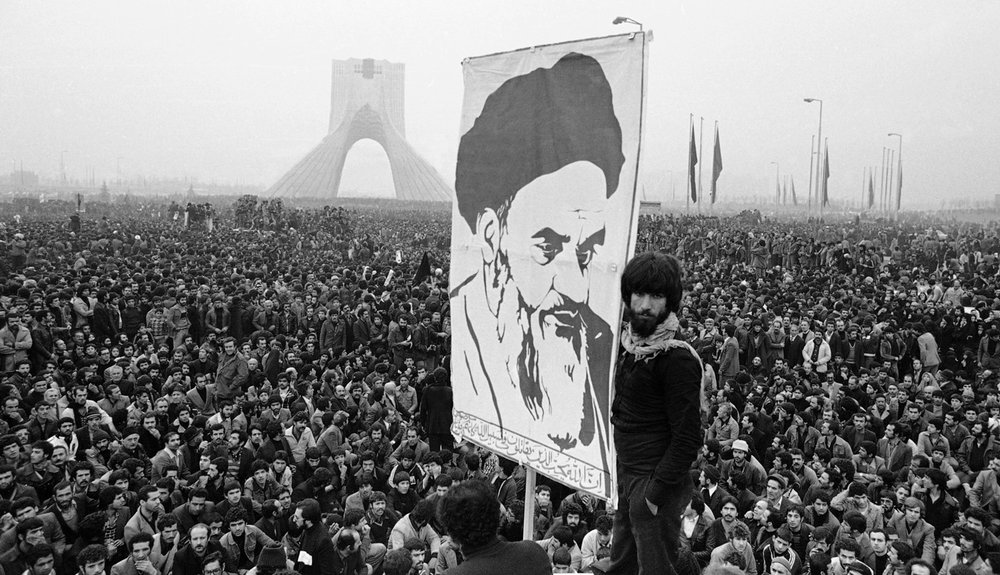

Three decades before the “War on Terror” and its orientation of “Islamic terrorism” as the principal threat to American security, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was its standing talisman. The color and contours of his very being – from his black turban to the long silver beard, represented the sum of all Muslims for Americans. The nation he remade into an Islamic theocracy, birthed by the very popular protests that menace it today, conflated popular understandings of “Muslim” with developing stereotypes of “terrorism.”

From November 4, 1979, through January 20, 1981, Khomeini and the new regime he helmed emerged as the new symbols of a global Islamic threat for the United States and its allies. The American imagination, and the swelling audiences glued to nightly news screens and daily paper headlines, was taken hostage by the pull of fear and disaster that unfolded in Tehran, which still penetrates more than four decades after those stunning events.

Months after a popular revolution unseated the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and the Islamic regime took hold of power, Khomeini loyalists stormed the American Embassy in Tehran. In the eleven months after the rise of Khomeini and the fall of the Shah, the American Embassy transformed from the site of the nation’s greatest ally into a symbol of western transgression, which marked the 52 Americans held hostage within it as bounty for devotees enraptured by Khomeini’s rising cult of personality.

“Death to America,” chanted at every stage of the Revolution, evolved into enshrined state slogan after Khomeini became supreme leader on January 16, 1979. The overpowering symbol of the Islamic Revolution resonated beyond Iran, and initially, even transcended sectarian bounds to inspire Sunni Muslim movements across Arab and Muslim-majority nations in the region. With the success of the revolution, the “Death to America” call trumpeted from the very Tehran streets where Americans flags were trampled upon, shapeshifted into protests against neocolonialism, and a powerfully galvanizing banner waived across the region by rising factions standing against American hegemony.

Seemingly overnight, these three words – “Death to America” – rose from the revolutionary squares of Iran’s grassroots into the main streets of the global Muslim and American imaginations. For the former, the slogan represented the possibility of self-determination for postcolonial Muslim societies suffocating between Soviet aggression and American Empire. Even more, it offered the possibility for a third space within a geopolitical landscape where Islam could reign supreme and steer nation-state governance. However, for the latter, “Death to America” gave definition and meaning to the brooding image of a man who would become the picture-perfect archetype of the Islamic threat. The ideal verse for a villain who represented everything America was not gave rise to an American reorientation of an Islam that it caste as “antithetical to civilization,” while simultaneously casting Khomeini as the face of this impending civilizational standoff.

Through the rapture of fiery rhetoric and revolution, Khomeini rose from holding “no material resources, [no] political party, [and] without the support of a single foreign power” to the highest rungs of political power in Iran. In the process, he rose to represent an Islamic menace that would inspire the fear of Americans for years to come.

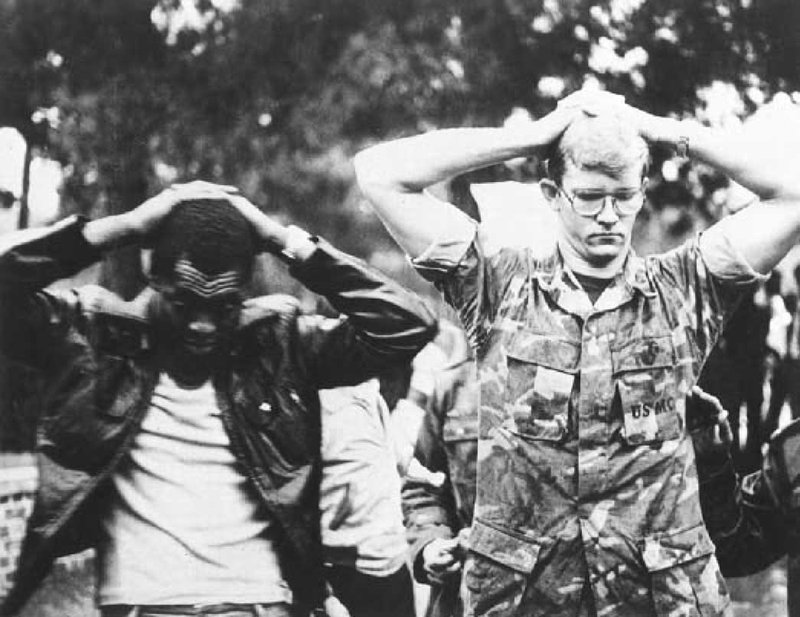

Those fears were realized on Sunday, November 4, 1979. After days of planning, the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam’s Line stormed the American Embassy like they did the streets of Tehran during the thick of the Revolution. The young Khomeini loyalists aimed to cease American presence within Iran and seize its final remnant. “Death to America,” on that Sunday and the two years that followed, evolved from fighting words to full-fledged action – armed and violent action – carried out by the turbaned and bearded men that took the Americans hostage. Inflamed by President Carter’s decision to grant refuge to the unseated Shah, and the American government’s longstanding abetting of dynastic monarthy in Iran, the hostility that led to the hostage crisis was rooted deeply.

For the 444 days that followed, the “Iran Hostage Crisis” provided real-time theatre for America’s contemporary clash with Islam. The events inside the Embassy-turned-holding cell produced reels of images of brown Muslim men overpowering white Americans, tying them down and torturing them. These sights formed the embryo for how modern Muslim threat was reimagined in the post 9/11 era, constructed in the very brown and brooding, bearded and turban-clad image of the masculine Muslim threat embodied by the hostage takers, and the iconoclast leader they emulated. The hostage takers, by their actions and their embodiment of brooding Muslim masculinity, pushed then President Jimmy Carter (who would lose reelection because of these events in Tehran) to brand the Iranian culprits with the title so intimately conflated with Muslim identity today: “terrorists.” The label struck a powerful chord in the minds of the American public, and four decades later, still sticks ominously onto Muslim men who look like the culprits.

This charge of terrorism, with Khomeini oriented as its head conductor, became rooted in the American psyche as millions tuned into the reel of live coverage that unfolded on their television screens. On legacy news programming every evening, and the upstart cable outlet CNN that made its name on the Hostage Crisis, Americans took in the nascent faces and ominous phrases that formed the emerging Islamic threat that paralleled Soviet aggression.

Khomeini, at every turn and on every channel, was ubiquitous. Those piercing brown eyes in between that signature black turban and silver beard were front and center, in real time and around the clock, penetrating past screens and standing in the center of American living rooms and the collective psyche of a society grappling with a new kind of enemy. In American Islamophobia: Understanding the Roots and Rise of Fear, I wrote, “The fear stoked by the mainstream news also warned of a Muslim takeover stateside, corroborated in the minds of viewers by the rising Muslim population and the ‘significant rise in the number of mosques and Muslim associations in the 1970s and 1980’s.” The line between objective news reporting and fearmongering blurred with regard to coverage of the Hostage Crisis, as it stirred concern about a rising Muslim population bent on taking over American neighborhoods, replacing churches with mosques, and on a scale far grander than an Embassy, taking America hostage.

With Khomeini and the Hostage Crisis, Islamic threat mutated from a confined secondary menace to a fully formed transnational threat, which imperiled the United States from without and from within. The hostages taken inside of the American Embassy on 1727 Taleqani Street in Tehran foreshadowed, in the mind of the American public, a grander takeover that could descend on Main Street.

Decades later, well-rounded realities were taken hostage by flatheaded myths. The Hostage Crisis staged in the center of the American Embassy in Tehran offered more than just stunning metaphor; it became the first stanza of the modern propaganda plays that constructed the character of “Islamic terrorism,” that still takes centerstage in the American imagination today.

When Iranian students stormed the American embassy that fateful Sunday in November 1979, the Ayatollah Khomeini took the American psyche hostage for the decade that followed. Buoyed powerfully by an American propaganda machine that willingly amplified his description of America as “The Great Satan,” and featured him incessantly at the center of television screens, newspapers, and the coveted cover of Time.

Nineteen seventy-nine and the decade that followed were his time. In Khomeini, the turban-clad followers that surrounded him, and the expanding Islamic threat he came to personify, America found a timely villain poised to replace the Soviets and its thawing threat in the era to come. A new political scapegoat that would justify American divide and conquer designs in the Middle East. A new antagonist in a civilizational standoff between good and evil. And, a new face of a transnational terror threat that, despite its sectarian rifts and racial heterogeneity, remains profoundly made in his image.

Khomeini came to embody how masculine Muslim terror is imagined, constructed and then stereotyped. Despite being Iranian and Shia Muslim, the force of his physical being blurred sectarian and ethnic divides, and blended Arab and Iranian, Middle Eastern and Muslim into the indistinguishable monolith that drives private Islamophobia today. If asked to assemble a “Muslim terrorist” from scratch, most Americans would grab hold of a turban, beard, brown skin, and black garb as the integral parts. Parts believed to be integral because they saw them in Khomeini, long before Osama Bin Laden or the Taliban, ISIS or even Sikh men stirred up the constructed stereotype of Islamic threat.

Khomeini, the man, may be long gone, but his imprint is timeless. His likeness continues to shape how Islamic terrorism is constructed and caricatured, deployed and disseminated during a War on Terror that Khomeini, himself, never lived to see. Khomeini stood on the other side of what America saw in itself; and shortly after taking power in Iran, took possession of the vacant seat within an American political imagination in search of a new enemy.

“To define themselves, people need an other.” writes Samuel P. Huntington in Who Are We?, a follow-up to his (in)famous The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. The phrase testifies to that uniquely American impulse to create mythic Manichean divides as existential mirrors and political expedients; to make perfect monsters out of imperfect men to meet the marching orders of empire. More than twenty years before Islam claimed that unenviable seat as America’s principal enemy, Khomeini and the hostage crisis provided the United States with a new a face and faith to fear. The Iran Hostage Crisis served as the first modern stage for the Muslim terrorist stereotype that took full form decades later, and remains deeply embedded in the minds of Americans and the War on Terror machinery that marches forward.

Khaled A. Beydoun is a law professor and public intellectual. He is the author of the critically acclaimed American Islamophobia: Understanding the Roots and Rise of Fear, and the forthcoming book The New Crusades: Islamophobia and the Global War on Muslims. He was voted among the 500 Most Influential Muslims in the World, and is a native of Detroit, Michigan. You can follow him and his work at @khaledbeydoun on all social media platforms.