By Cori Brosnahan

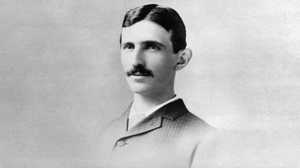

“Nikola Tesla is almost the tallest, almost the thinnest and certainly the most serious man who goes to Delmonico’s regularly,” wrote the reporter Arthur Brisbane for the New York World in 1894. [1]

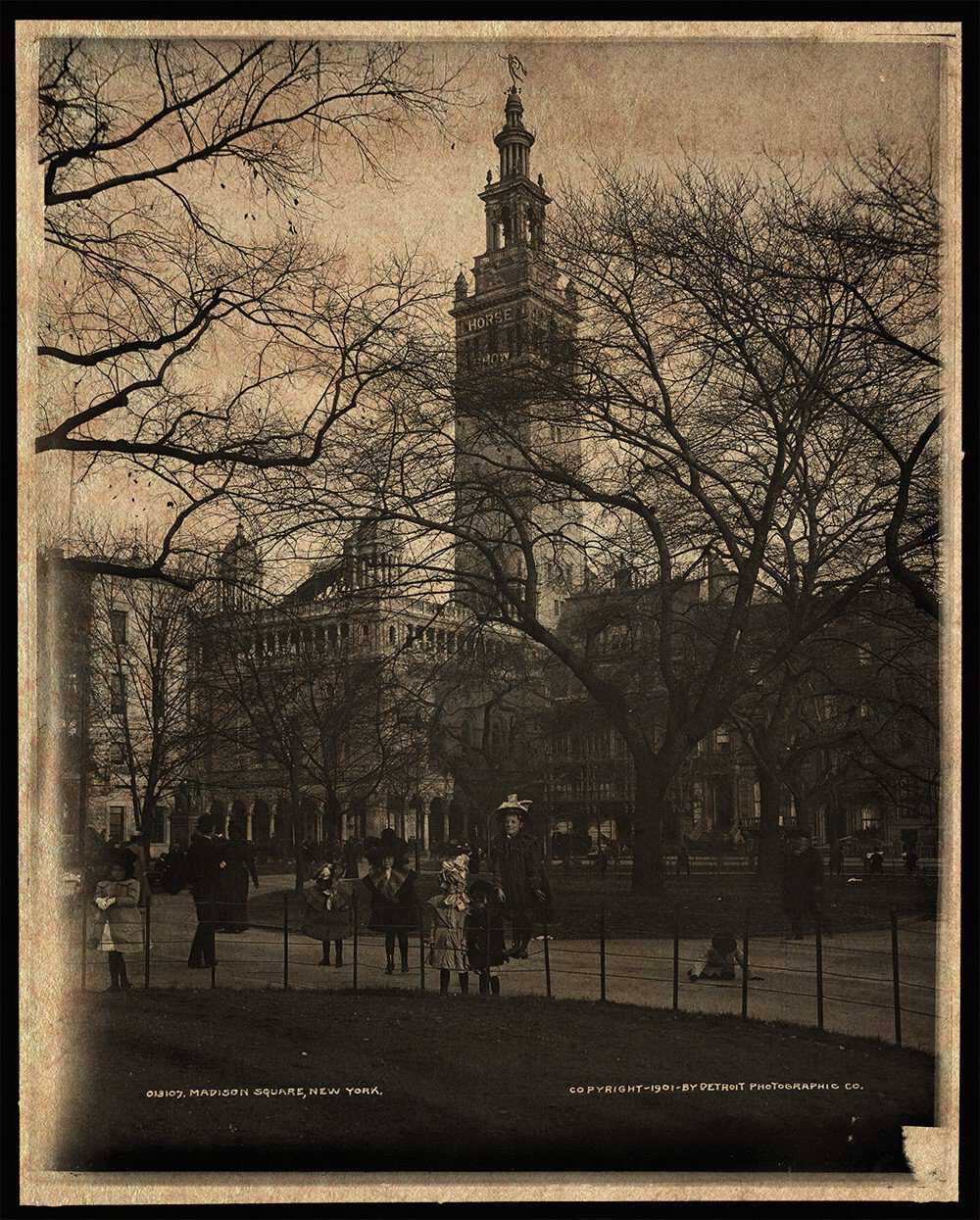

Delmonico’s, situated in Madison Square, was one of the most stylish restaurants in Manhattan, frequented by the city’s social elite. Nikola Tesla, the brilliant inventor whose ideas about electricity revolutionized the world, was in the habit of stopping by the popular establishment for a meal after working in his lab all day. There in Delmonico’s grand dining rooms, Tesla would have run into the artists, intellectuals and businessmen whose ideas shaped the cultural life of the country at the end of the 19th century.

We picked four of them to try and understand how the inventor fit into the context of his time: Robert Underwood Johnson, an influential editor; John Muir, the famed naturalist; Mark Twain, the beloved writer; and Stanford White, an architect who was swiftly sculpting the New York City skyline.

Imagine them sitting at a table together, enjoying Delmonico’s signature Chicken à la King. What would they have talked about? What ideas might have been shared? What conclusions drawn?

Pass the salt and read on.

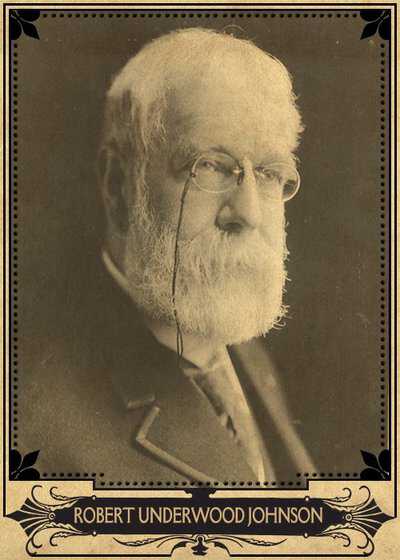

Robert Underwood Johnson: Editor, Genius-Whisperer

Table talk: Serbian poetry, the perils of the yellow press, Tesla’s uncanny prophecies

“Among the few persons whom I have met who I think are possessed of genius is my friend Nikola Tesla, the electrical discoverer and inventor,”[2] Robert Underwood Johnson wrote in his memoir, Remembered Yesterdays. And that was saying a lot — because Johnson knew just about everybody.

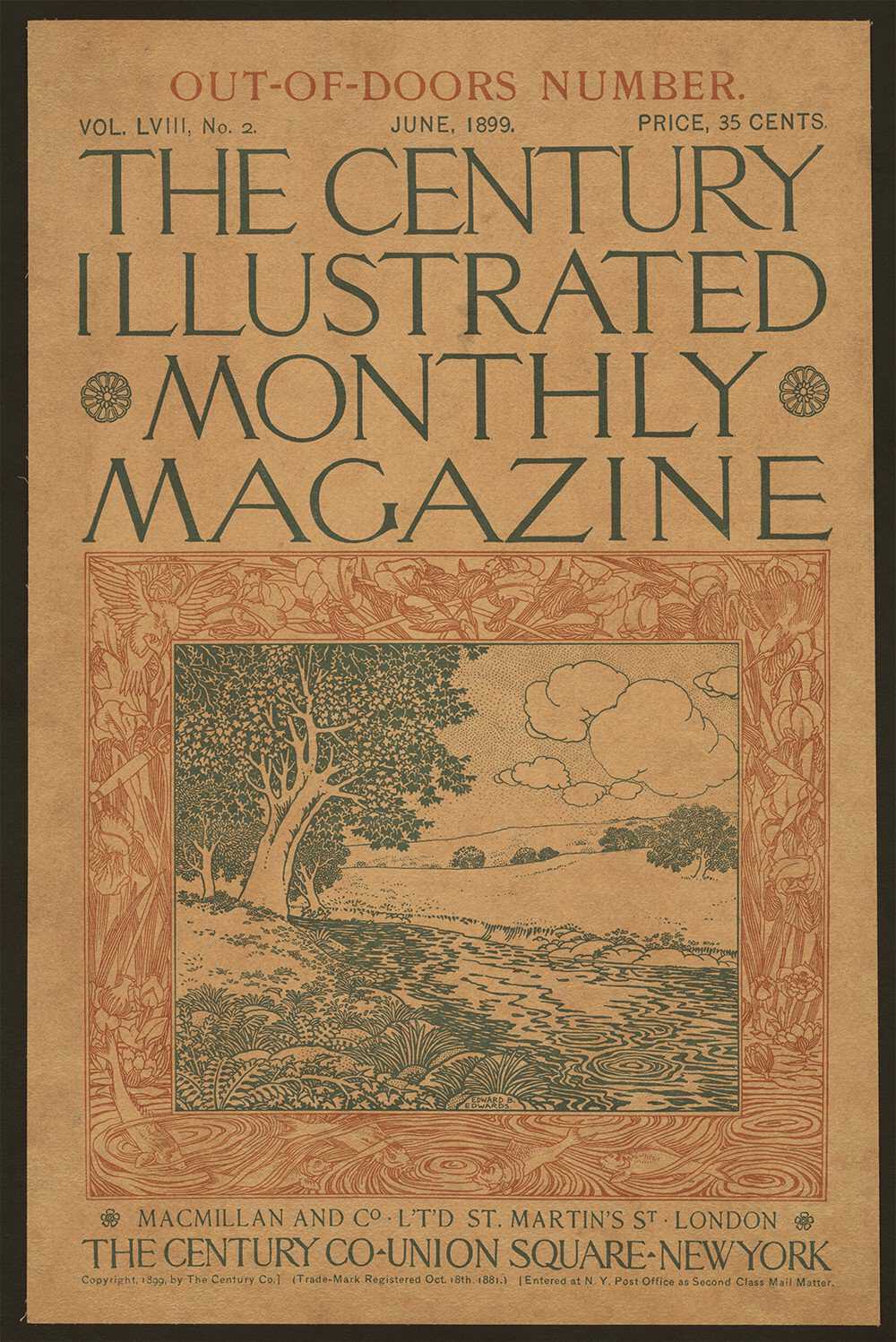

As an editor at the influential magazine, Scribner’s Monthly, and its successor, The Century, Robert Underwood Johnson played a significant role in shaping the cultural life of New York and the East Coast. With his finger on the intellectual pulse of the country as it barreled into the 20th century, he reached out to everyone who piqued his interest, urging them to write for his publications. Johnson was an enthusiastic supporter of causes he believed in, and the ultimate champion of his friends. “You could just feel him towering over somebody, saying ‘get busy, do this, do that,” says Donald Worster, professor emeritus of history at the University of Kansas.

When Ulysses S. Grant lost virtually all his money overnight, thanks to a shady business partner, it was Johnson who convinced him to write about his experiences in the Civil War. The four articles he produced for The Century magazine became the foundation for Grant’s memoirs, which were received with universal acclaim and allowed the general to leave his family well-endowed when he passed away shortly after completing the manuscript.

The editor was also an environmental activist. On a trip to California, he met John Muir, who became a friend and fellow preservationist. “He was the one who goaded Muir into doing more than just writing and enjoying himself, but to really take an active political hand,” says Professor Worster. “He continued to pressure Muir from that point on.” Muir’s passion combined with Johnson’s political savvy had immediate results; Yosemite became a national park not long after the two met.

Johnson became acquainted with Tesla through T.C. Martin, an engineer who profiled the inventor for The Century. The usually solitary Tesla was embraced by Johnson and his wife, Katharine, whose home at 327 Lexington Avenue in New York was a nexus of big thinkers and their ideas. It was there that Tesla would have encountered other cultural luminaries of the day, including John Muir, Mark Twain, and Stanford White.

Tesla and Johnson bonded over a love of poetry. The inventor nicknamed his friend “Luka Filipov” after a Montenegrin hero memorialized in an eponymous poem by Serbian poet Jovan Jovanović Zmaj. Tesla’s translation of the poem appeared in The Century magazine.

The Century also published photographs of Tesla’s lab, and essays like the controversial “The Problem of Increasing Human Energy,” which brought the inventor’s work and ideas to the general public. In the 1890s, newspapers were vying to attract readership by sensationalizing the news — a tactic known as “yellow journalism.” Protective of his friend, the media-savvy Johnson disparaged the way the yellow press seized upon some of Tesla’s more unorthodox projections.

“The imaginative character of Tesla’s work made him the prey of the sensational press, which… did everything it could to exploit him for its cruel and sordid purposes, with the result of making him ridiculous only to those who had neither knowledge nor the responsibility of sober judgment.”[3]

Johnson’s worries about his friend’s reputation — and, by extension, his legacy — proved well-founded; Tesla was largely left out of 20th century history books. “Since most people assumed that Tesla was a mystic who did not use theoretical science to develop his inventions, he could hardly be invoked by those apostles of modernity who believed that technology grew out of research performed by scientists in university and corporate laboratories,”[4] writes Bernard Carlson in his biography of the inventor, Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. By the time of his death, Tesla had become a caricature in the public imagination: “effete, elitist, and, well, eccentric.”[5]

Amongst those who recognized that Tesla was ahead of his time, Johnson wrote:

“My deepest regret is that I did not make record of the many prophecies which he made in my house, a number of which have since ‘materialized,’ but which then were thought to be the wildest fancies.”[6]

Today, of course, Tesla is a counterculture folk hero, an acknowledged godfather of modern technology. Not to mention, he has a famous electric car company named after him. Robert Underwood Johnson would have approved.

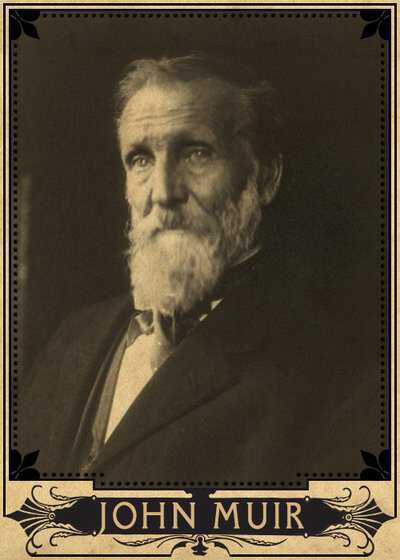

John Muir: Naturalist, Amateur Inventor

Table talk: nature’s purpose, wacky childhood inventions, a trip to Alaska

In May of 1893, the man known as “John of the Mountains” traveled east from his home in California and spent a few days at the Chicago World’s Fair. Wandering past art galleries, birch bark wigwams, and life-size reproductions of Christopher Columbus’s ships, he judged the affair “a cosmopolitan rats nest containing much rubbish & common place stuff as well as things novel & precious.”[7]

Among those “novel & precious” sights was the “City of Light” — which is what the fairgrounds turned into at night when a hundred thousand incandescent lamps illuminated its neoclassical silhouette. The effect struck Muir as magnificent. In a letter to his wife, Louie, he wrote:

“Last night the buildings and terraces and fountains along the canals were illuminated by tens of thousands of electric lights arranged along miles of lines of gables, domes, and cornices, with glorious effect. It was all fairyland on a colossal scale and would have made the Queen of Sheba and poor Solomon in all their glory feel sick with helpless envy.”[8]

The spectacle was the handiwork of Nikola Tesla, who, with his financial backer, George Westinghouse, outbid a rival team of Edison and J.P. Morgan for the contract to light the first all-electric fair in history.

Muir was soon hearing about Tesla through their mutual friend, the ever-sociable Robert Underwood Johnson, who met Tesla around the same time the World’s Fair closed in the fall of 1893. Through Johnson, an introduction was made for the naturalist and his wife:

“You are very kind in promising to send us Tesla. I shall be delighted to know him. He seems to be one of a thousand thousand & more. Mrs. Muir seems to know him well already, though they have not met. She says that he knows far more of the Lord’s lightening than Edison.”[9]

That meeting, when it happened, appears to have gone well, and more followed. “Tell Electric Tesla that I feel his draw over all the continent, & will gladly give way to it whenever I can,”[10] Muir wrote to Johnson in January of 1898.

On the surface, Muir and Tesla seem like an odd couple. Both were great observers of nature, but they observed it in different ways.

“For Muir, nature meant the great geological forces and the botanical forces,” says Donald Worster, author of A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir. “For Tesla, you might say nature was encountered in a laboratory. And his interest in it revolved around how he could use it and turn it to some sort of practical advantage.”

In other words, when Muir looked at Yosemite Falls, he saw something sacred, to be revered and protected. When Tesla looked at Niagara Falls, he saw a hydroelectric power plant.

Still, the two men had something significant in common: Both were inventors.

As a boy in Wisconsin, Muir was known throughout the region for his inventions. Mostly carved from wood, they included locks, clocks, and water wheels. Ever the disciplined student, he even invented a desk that helped him study by retrieving his lesson books one at a time from a rack and displaying the text for precisely the time it took to study his mathematics or botany before moving on to the next.

Muir didn’t condemn modern industrial technology either. In his youth, he worked setting up sawmills in Canada and became the foreman of a wagon wheel factory in Indianapolis. He was so fond of trains that he let railroad tracks cut right through his orchards, and in his old age he was photographed enjoying rides in automobiles. “Muir wanted to leave parts of the world wild,” says Worster. “He thought the most spectacularly beautiful places should be left wild and we should stand in some awe of them, but he was not against science, technology, progress.”

And though he came to nature with a religious spirit, he also approached it with an engineer’s desire to understand how it worked. “It wasn’t just looking at it in pictures,” says Worster. “If you read any of his books, when he looks at mountains, he’s really interested in how valleys get carved, the making of things, the natural processes.”

It was perhaps this curiosity that drew him to Tesla. After a fire destroyed Tesla’s New York City laboratory in 1895, Muir urged Johnson to invite Tesla on their trip to Alaska. Highlighting his bond with the Serbian inventor, Muir wrote:

“Fiery Tesla of course ought to go to Alaska to blend his fire & Aurora in ice. I’m sorry for Tesla in loosing [sic] his models & papers etc but not half so sorry as you are. As an inverntor [sic] I know that everything is saved in his own brain. & no burning that spares Tesla can possibly be very significant. Now do come & I’ll go. Mrs. M. is wild to see Tesla.” [11]

Alas, the two inventors never did go together to the tundra. As Johnson replied to Muir, “Tesla cannot be counted upon in a matter of this kind.”[12]

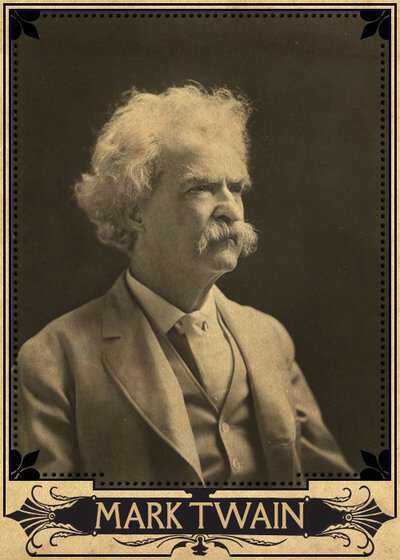

Mark Twain: Writer, Social Philosopher

Table talk: patents, utopianism, mutually assured destruction

“Nov. 1, 1888. I have just seen the drawings & descriptions of an electrical machine lately patented by a Mr. Tesla, & sold to the Westinghouse Company, which will revolutionize the whole electric business of the world. It is the most valuable patent since the telephone.”

– Mark Twain’s Notebooks & Journals, Vol. III

Mark Twain, like most of his generation, was fascinated by electricity. By the end of the 19th century, the promise of the machine age had been dampened by long work days, factory fires, and wheezing lungs. Then along came Thomas Edison’s commercial light bulb. While skeptical that the new technology would actually improve their lives, people were still drawn to it.

“It’s interesting and beautiful — you don’t have to worry about it poisoning you in your sleep like gaslight,” says Jennifer Lieberman, author of Power Lines: Electricity in American Life and Letters, 1882–1952, (forthcoming from MIT Press). Where machines were perceived as repetitive, harsh, and dirty, electricity was austere and mysterious, naturally-occurring in nature, and part of American mythology in the form of Benjamin Franklin’s kite.

Twain, who had a few patents of his own [13] and was exuberantly interested in anyone and everyone doing new things, made a habit of writing to both Tesla and Edison. Though the surviving correspondence is scarce, there does seem to be a pattern: “When he wants something practical built, he got in touch with Edison,” says Lieberman. “When he’s writing about talking to Tesla, he’s talking about much more abstract things.”

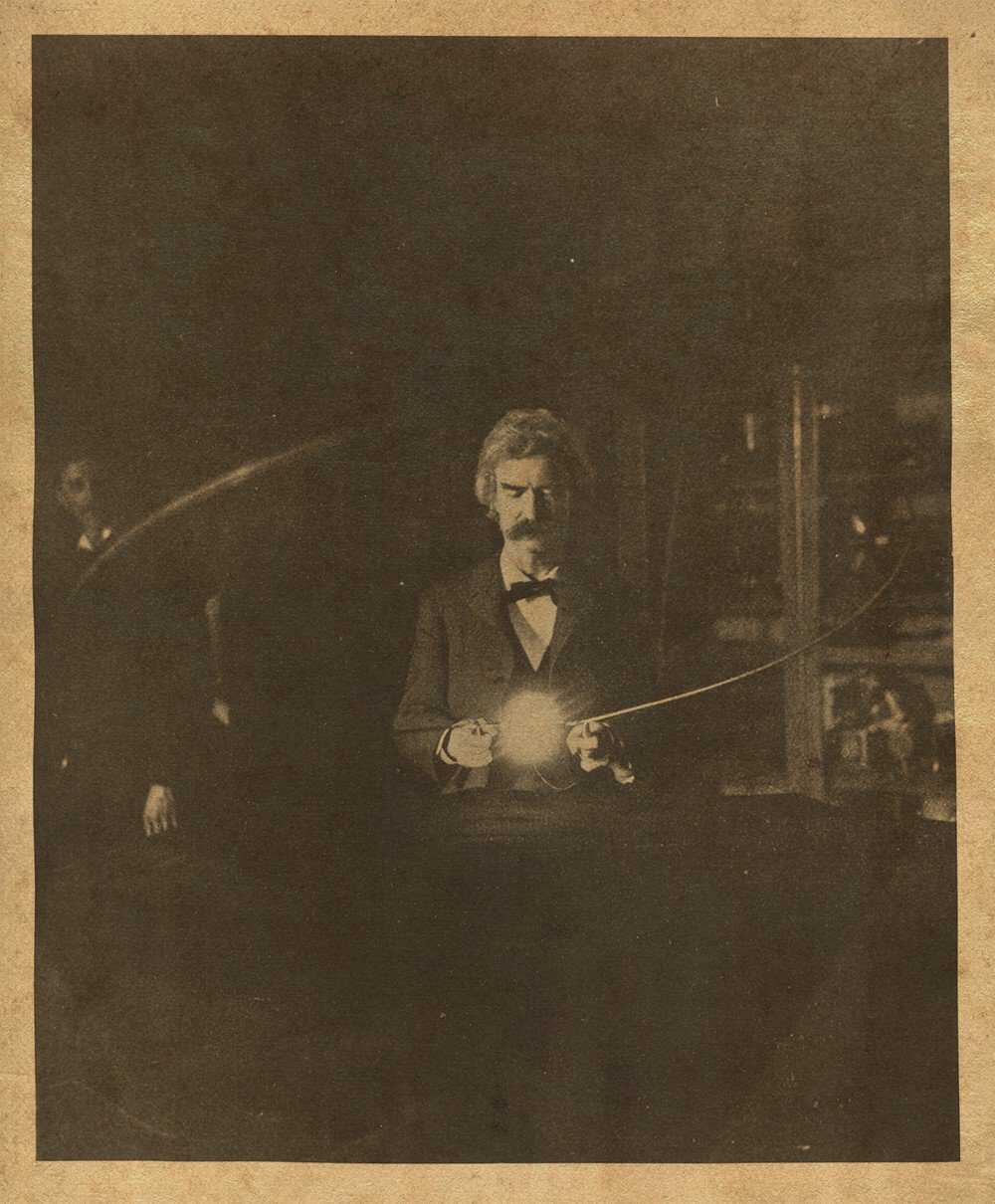

For good reason. While most engineers were trying to make electricity cheaper, Tesla was fixated on how to transmit electricity wirelessly — then a problem no one really thought needed solving. Ostracized from the practically-minded engineering community, Tesla was embraced by writers like Twain, who were concerned with the new technology’s social and philosophical implications. Tesla welcomed the attention; a consummate showman, he gave public demonstrations of his inventions and invited friends like Twain to visit his laboratory.

“He’s basically a Bill Nye the Science Guy or Mr. Wizard a hundred years before those science popularizers are there,” says Lieberman. “He was showing people who are excited about these possibilities that they can hold electricity as this unruly and mysterious-seeming energy in their hands. And then he’s saying ‘this will change society.”

Not just change society, but perfect it. According to Lieberman, “Tesla actually believes that the world can be made a utopia — as in, a place with without violence or fear of hunger — by controlling electricity.” He even attempts to prove it with a series of dubious scientific assumptions in his controversial essay “The Problem of Increasing Human Energy in The Century.”

Twain, on the other hand, was no utopian — and as fascinated as he was by it, he had his qualms about technology. In his novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, published in 1889, an engineer travels back in time from the 19th to the 6th century. Armed with his knowledge of the future, the engineer attempts to modernize and improve the lives of the people. But it’s not long before his “civilizing” technologies turn into weapons — including electricity, which is employed to electrocute an army of antagonistic knights.

“I would say Mark Twain believes that humans are flawed, and you just can’t get to a place of perfection,” says Lieberman. “But I also think you can’t write about those things unless you have some hope that you can change them.”

There in the inventor’s laboratory was the possibility — however improbable — for change. And so, in November of 1898, a prescient Twain writes to Tesla from Europe, [14] suggesting a means for peace in an increasingly hostile world: mutually assured destruction.

Dear Mr. Tesla

Have you Austrian + English patents on that destructive terror which you have been inventing? — + if so, won’t you set a price upon them + commission to sell them? I know cabinet ministers of both countries — + of Germany, too; likewise William II.

I shall be in Europe a year, yet.

Here in the hotel the other night when some interested [unreadable] were discussing [means] to persuade the nations to join with the Czar and disarm, I advised them to seek something more sure than disarmament by perishable paper contract — invite the great inventors to contrive something against which fleets and armies would be helpless, + thus make war thenceforth impossible. I did not suspect that you were already attending to that and getting ready to introduce into the earth permanent peace + disarmament [in a] practical and mandatory way.

I know you are a very busy man, but will you steal time to drop me a line

Sincerely yours,

Mark Twain

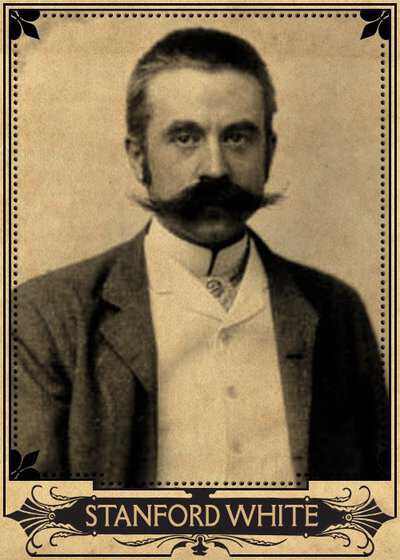

Stanford White: Architect, Tastemaker

Table talk: Wardenclyffe, the New York City landscape, workaholic sleep habits

When it came to thinking big, Nikola Tesla had few peers. But the architect Stanford White was one of them.

“[White] was so excited by the nature of change,” said longtime New Yorker writer Brendan Gill in the American Experience documentary Murder of the Century. “When automobiles came in, he had to go faster between New York and his house in St. James, Long Island than anybody had ever gone before. He was mad to make use of the telephone. He loved going back and forth to Europe on the fastest ships — everything was going at full tilt.”

His energy and extravagance reflected the Gilded Age as a whole. The 1870s and 1880s saw an era of rapid economic growth in the United States. By 1906, a handful of American families controlled the majority of the country’s wealth.[15] Stanford White catered to the newly affluent, building their mansions in Newport and Long Island, as well as places for them to play, like Madison Square Garden. By the time of White’s death, his firm, McKim, Mead and White, was one of the most successful architectural outfits in the country.[16]

Tesla and White first met at the Garden in 1891, when both attended a concert by piano virtuoso Ignace Paderewski.[17] They were brought together again two years later by the Chicago World’s Fair, in which both participated. Not long after, White invited Tesla to join The Players, an elite social club with headquarters — designed by White — in a Gramercy Park townhouse.

It was an unlikely friendship in some ways. White was described as “masterful,” “intense,” “burly yet boyish.”[18] Tesla frequently appeared pale and drawn. White was the consummate man-about-town, a fixture on the New York party circuit. Tesla was a more serious figure. White was also a ladies’ man, whose risque private gatherings and many affairs were legendary. Tesla, meanwhile, was presumed celibate by many of his friends: “I fear he will go on in the delusion that woman is generically a Delilah who would shear him of his locks,”[19] T.C. Martin once wrote to their mutual friend Robert Johnson Underwood.

But both were creatures of New York City — workaholics, who shared a drive and ambition that shaped the age in which they lived. While Tesla reportedly worked for days without rest, White, according to his great-granddaughter, Suzannah Lessard, was “enormously productive, always working, always designing, carrying as many as 60 projects at a time.”[20] Tesla would change daily life with his alternating current motor. White transformed the landscape of New York and the Northeast with his buildings. White himself lived in one of his creations, a tall tower above the Garden, where he “often talked with Tesla about their shared vision of the future.”[21]

That shared vision was realized in the form of Wardenclyffe tower, Tesla’s most ambitious project yet. Financed by J.P. Morgan, the tower was intended to demonstrate Tesla’s ideas about wireless power transmission. The inventor claimed that from its location in Shoreham, New York, the tower would be able to transmit messages across the Atlantic.[22]

Tesla asked White to design the laboratory below the tower where he planned to demonstrate his ideas about wireless telegraphy. A simple, one-story brick building with arched windows and a tall chimney, the laboratory would be White’s last design.

On June 25, 1906, White was murdered by millionaire Harry Thaw, who accused the architect of raping his wife, Evelyn Nesbit, when she was 16 years old. The daily newspapers seized upon the the scandal. White’s reputation was ruined. His friend Nikola Tesla was one of the few people to attend his funeral.[23]

Tesla and White’s shared project was similarly doomed. When Tesla ran out of money, Morgan refused to give him more. Wardenclyffe Tower was demolished for scrap material in 1917. The humble building that Stanford White designed still stands.

Published October 18, 2016

1 Carlson, Bernard. Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. p.3.

2 Johnson, Robert Underwood. Remembered Yesterdays. p. 399.

3 Johnson, Robert Underwood. Remembered Yesterdays. p. 401.

4 Carlson, Bernard. Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. p.397.

5 Carlson, Bernard. Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. p. 398.

6 Johnson, Robert Underwood. Remembered Yesterdays. p. 400.

7 Letter from John Muir to Louie [Strentzel Muir], 1893 May 29.

8 Letter from John Muir to Louie [Strentzel Muir], 1893 May 29.

9 Letter from John Muir to [Robert Underwood] Johnson, [1894 ?] Jan 21.

10 Letter from John Muir to [Robert Underwood] Johnson, 1898 Jan 7.

11 Letter from John Muir to [Robert Underwood] Johnson, 1895 Mar 23.

12 Letter from R[obert] U[nderwood] Johnson to John Muir, 1895 May 14.

13 Among them, an Improvement in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments (arguably, the modern bra strap), a history trivia game, and a self-pasting scrapbook.

14 Letter, Photostat copy, Swezy Papers (Box 17): Mark Twain Folder, National Museum of American History.

15 American Experience. Murder of the Century.

16 American Experience. Murder of the Century.

17 Seifer, Marc. The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla: Biography of a Genius. P. 159.

18 Uruburu, Paula. American Eve. p.114-115.

19 Seifer, Marc. The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla: Biography of a Genius. p. 127.

20 American Experience. Murder of the Century.

21 Seifer, Marc. The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla: Biography of a Genius. p.159.

22 Carlson, Bernard. Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. p. 313.

23 Seifer, Marc. The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla: Biography of a Genius. p. 322-323.