Presidential Politics

On October 14, 1912, Progressive Party presidential candidate Theodore Roosevelt delivered one of the most remarkable campaign speeches in American history. Wounded in the chest by the bullet of a would-be assassin, Roosevelt spoke passionately and eloquently for 90 minutes, extolling the virtues of Progressivism to a crowd in Milwaukee. While Roosevelt's campaign would ultimately fail, this moment, brimming with blood and passion, represented one of the finest hours of a man who, from the moment he entered presidential politics, made his life a continuous campaign.

As a vice-presidential candidate in 1900, Roosevelt stumped tirelessly for his Republican running mate, William McKinley. TR traveled thousands of miles to speak out against Democrat William JennigsBryan's international isolationism and to laud traditional Republican virtues such as personal responsibility.

Roosevelt loved being seen and loved being heard. He smiled and waved, ranted and raved, hammering a clenched fist on his palm for emphasis as crowds cheered him on. In the end, McKinley-Roosevelt won by a landslide. On September 14, 1901, when William McKinley died of bullet wounds inflicted by an assassin, Theodore Roosevelt became the nation's 26th president.

For the sake of national stability, Roosevelt continued McKinley's conservative policies until early 1902, when he began a campaign to regulate corporate interests and protect the interest of the average citizen. This was a bold move, Roosevelt believed that the votes of the common man represented more political power than the political machines, and that his progressive policies would pave his way to reelection.

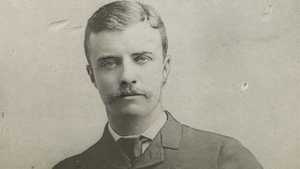

A skillful manipulator of the media, Roosevelt transfromed the presidency. He held daily press briefings, giving insider tips to those reporters who responded with favorable stories. The White House welcomed cowboys and sculptors, intellectuals and prizefighters, and the public grew fascinated with the presidency -- and with TR. He was the first President to be photographed in action. His name and image were everywhere.

Political tradition proscribed campaigning by incumbent presidents, but in 1904, Roosevelt's years of campaign by legislation paid off. He won the largest popular and electoral majority of any incumbent president in American history, then promised never to run for the presidency again. It was a promise he did not keep.

William Howard Taft, Roosevelt's hand-picked successor to the White House, promised to carry out a progressive agenda, but as his administration wore on, he became more and more conservative. The rift between the conservative and progressive wings of the Republican party grew. In 1912, some progressives called for the formation of a third party with Roosevelt. At first, Roosevelt resisted, looking ahead to a possible 1916 campaign. But after a series of confrontations with the Taft administration, Roosevelt leapt into the ring to oppose the president of his own party.

A political brawl of the lowest order ensued. TR announced Taft had "brains less than a guinea pig," while Taft called TR a "demagogue," and questioned his veracity. In a typically fiery nationwide tour, TR hammered Taft and the Conservatives mercilessly, winning the support of the common folk and delegates from those states that held primary conventions. But at the Republicans' national convention, the tide turned. The Republican machine supported Taft. TR's delegates refused to vote, then walked out. During the following two months, they formed the Progressive, or Bull Moose, party and chose TR as their presidential candidate.

The 1912 presidential race became a two-man show starring TR and the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson, also a progressive politician. Americans would have to decide what kind of progressivism they wanted. Wilson called for a complete shutdown of the business trusts, but attempted to appease business people by asserting that other issues, such as woman's suffrage, should be decided state by state. Roosevelt campaigned on a platform of "New Nationalism," which included such reforms as women's suffrage, old-age pensions, and child labor laws. He called for the continuation of trusts but under government supervision, and advised their continued existence under government regulation.

The Bull Moose candidate drew enthusiastic crowds wherever he went -- the crowd in Milwaukee on October 14 was no exception. Wounded but still standing, Roosevelt implored Americans to vote for him, lest their country be divided into a nation of "haves" and "have nots." This was one of Roosevelt's finest hours, but drama could not outweigh the deadly split in the Republican party. On election day, Roosevelt bested Taft but lost to Wilson by more than two million votes. Theodore Roosevelt's last campaign was over, a decisive, if stirring, defeat.