Anne Morgan: Advocate for Women and Workers

Anne Tracy Morgan was the daughter of the most powerful financier in America's history, J.P. Morgan. Born on July 25, 1873, Anne Morgan grew up on her family's New York estate, and was schooled both at home and in private schools. As an adult, Morgan used her family's wealth and connections to bring attention to the women's suffrage movement and the plight of lower class immigrant workers. Her efforts helped advance women's rights and change labor laws.

As an adult, Anne Morgan dedicated herself to improving the well being of New York City's women. In 1903, she helped found New York City's first women's social club, the Colony Club. In 1909, Morgan worked with the National Civic Federation to provide food to underprivileged women workers in New York. In 1910 she joined the American Woman's Association (AWA), helping working women invest their own money to fund leisurely pursuits.

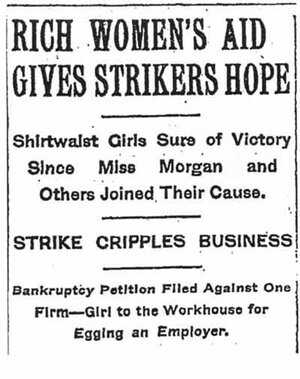

By then, New York City had become a hotbed of labor reform issues. Factory laborers, most of whom were women, worked long hours for low wages, often in cramped spaces. Their cause attracted attention from the Industrial Ladies Garment Worker's Union (ILGWU) and the Women's Trade Union League (WTUL), which helped mobilize worker strikes across the city. When several independent factory owners hired thugs, prostitutes, and private police to berate, beat, and cause turmoil along picket lines, Anne Morgan stepped in. With the help of other wealthy New York socialites such as Mary Dreier, Alva Belmont, and Elisabeth Marbury, she formed a committee within the WTUL to protect the strikers of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory from abusive forces.

Mockingly nicknamed the "mink brigade" because of their wealthy backgrounds, committee members helped fund the Triangle Factory workers' strike and garnered attention from the press. Morgan and her comrades occasionally walked the picket lines, themselves, believing that police were less likely to beat protesters with members of high society among them. When strikers were arrested, committee members often spent long hours in court paying strikers' fines, and the committee even brought legal action against the police.

Morgan was an advocate for women's and workers' rights, but she disagreed with the unions' rhetoric, which she viewed as Socialist. When Triangle Factory workers rejected a proposal that offered higher wages and shorter hours but no union, Morgan withdrew her support from the Triangle strike in early 1910. In February, Triangle workers conceded their demand for a union and accepted a proposal for shorter hours and higher wages.

Throughout the early 1900s, Morgan remained a member of the AWA and ATWUL, and continued her career as a suffragist and philanthropist, funding her endeavors with a $3 million inheritance she received upon her father's death in 1913. In 1915 she published a book on the education and responsibility of the American woman, and earned a medal from the National Institute of Social Science the same year. During World War I and World War II, Morgan spent time in France overseeing relief efforts in frontline communities. She established The American Friends for Devastated France, which worked to provide health services, housing, and food to soldiers and refugees displaced by occupation and evacuation.

Though Morgan claimed not to be a feminist, the majority of her work in the United States centered around the advancement of professional, working women. In 1927, Morgan stated that women "will take their places beside men as partners, unafraid, useful, successful, and free." She died January 29, 1952.