Helping People in Jail Exercise their Right to Vote in North Carolina

Activists find new ways to reach and educate incarcerated voters in swing state

This dispatch is part of a series in collaboration with The GroundTruth Project that explores the expansion of voting rights in communities across the U.S., in connection with The Vote, by American Experience, and as part of GroundTruth’s initiative called “On the Ground" with Report for America.

The COVID-19 pandemic has left voting rights groups nationwide scrambling to reach millions of potential voters to get them to register and cast ballots in this year’s presidential election.

For Caitlin Metzguer, deputy director of You Can Vote in North Carolina, the challenge is even more difficult. She and her volunteers are trying to contact thousands of people in jail who are likely unaware of their voting rights.

In any other election year, she and her volunteers would visit jail facilities to distribute voter registration forms and absentee ballot requests and use jail-approved pens to help inmates exercise their right to vote.

“It's going to be hard,” said Metzguer. “Unfortunately, there's not a good one-size-fits-all solution.”

In most states, individuals convicted of a felony lose their right to the ballot — at least temporarily. But people in jail awaiting trial have been able to vote since 1974, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that eligible voters in detention have a constitutional right to the ballot. The court leaves it up to local jurisdictions, however, to decide how they will ensure voter access.

The majority of people in jail are eligible voters because they have not been convicted of a felony crime, according to the Sentencing Project, which promotes justice system reform. As of 2017, 482,000 people, or nearly two-thirds of all jailed individuals nationwide, were in jail because they could not post bail, the Sentencing Project reported.

In North Carolina, prior to the pandemic, approximately 19,000 people were incarcerated in local jails. Voting has been sparse in those facilities and varies by county in the competitive swing state, which is drawing the attention of both major political parties.

Just 20 people are known to have voted inside North Carolina jails in the 2018 midterm elections, according to public records requests filed to each county by the reporter. Most were incarcerated in the same jail — the Durham County Correctional Facility, which works with You Can Vote to overcome common barriers to voting while incarcerated.

There are many roadblocks to voting while in jail. Many facilities do not readily provide voter registration or absentee ballot request forms. A person’s ballot may not arrive due to some jails’ mailing restrictions. But the biggest barrier is a lack of knowledge. Many detainees do not know they have a right to a ballot.

“People often think that they can't vote based on any criminal justice history at all,” said You Can Vote’s Metzguer.

Christopher Uggen, professor of sociology and law at the University of Minnesota, who researches felon voting rights, said what's happening in North Carolina amounts to “practical disenfranchisement" because an elected sheriff, for all intents and purposes, decides whether a jailed voter will have easy access to the ballot.

“The tension here is that [these] institutions often have some latitude [on facilitating voting] because their mission revolves around security,” said Uggen. So they may say that they are understaffed, he explained, or that they don't have the means to provide a polling place.

Uggen said the “unevenness” of jail voting raises Constitutional concerns under the 14th ammendment, which forbids states from depriving someone of their rights as citizens without due process.

Nonpartisan civil rights groups like You Can Vote, founded in 2014, help fill in the gaps by leading voter registration and absentee ballot request drives inside jails. The ad hoc process largely depends on partnerships with willing county sheriffs, who themselves are elected officials.

“How friendly the local jail is to 'get out the vote' efforts makes a big difference; it probably shouldn’t, but it does,” said Uggen. “Where it's been successful, you get buy-in from jail administrators and show that we can do this in a way that won't be intrusive or compromise security.”

In North Carolina, getting buy-in means obtaining permission from sheriffs in each of the state’s 100 counties.

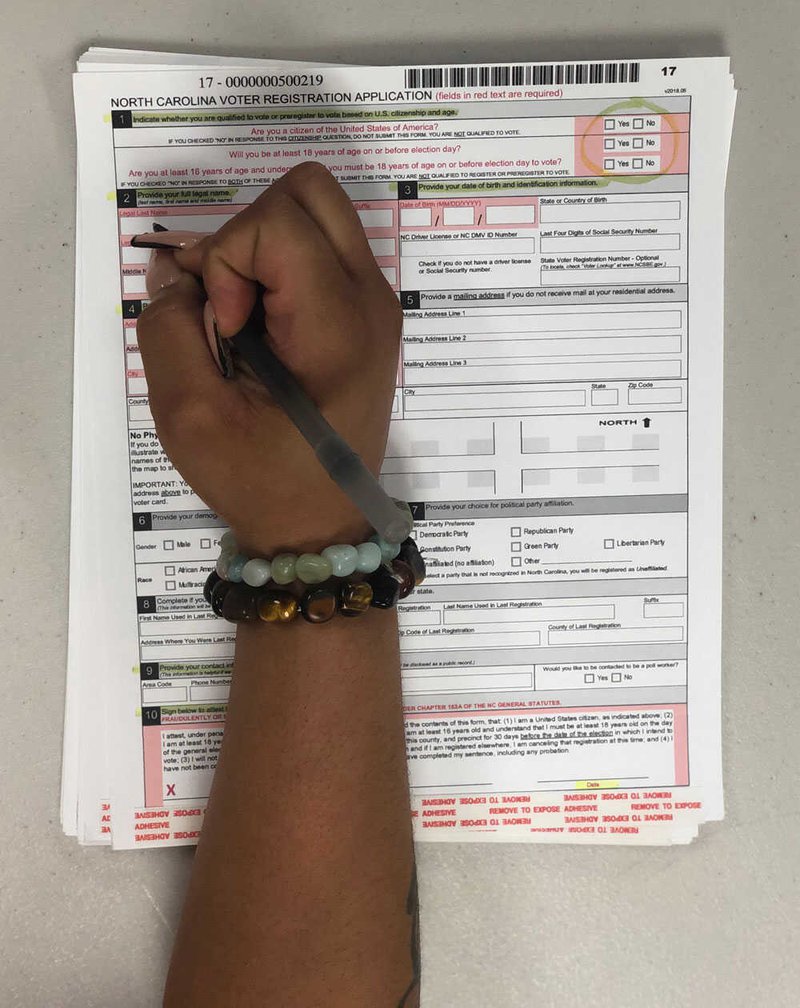

Previously voting rights volunteers entered jails and used the state’s official voter registration form to walk incarcerated people through determining if they’re eligible to vote.

Most are eligible, according to You Can Vote’s executive director and founder, Kate Fellman, who said volunteers help inmates register and assist them with filling out an absentee ballot request form.

The eligible voter is responsible for returning the ballot once it later arrives in the mail — but support from You Can Vote volunteers can help avoid many of the pitfalls along the way, according to Metzguer and Fellman.

“We help people know which parts of the forms are required, making sure that the handwriting is legible and that they know which address to use and making sure that they actually check the boxes that say, ‘I'm a citizen’ and ‘I'm 18,’” said Metzguer. “They’re seemingly small little details, but if they don't do them correctly the registration won't be processed.”

Such initiatives can have a significant impact on voter turnout.

Thirteen of the 20 jail votes cast in 2018 were from the Durham County Detention Facility, the jail with the longest partnership with the nonpartisan organization.

“People give hugs to our volunteers, people cry, people are excited to be enfranchised,” said Fellman. “Once they know they can vote, they want to. It's not for lack of want. It's for lack of education on their rights.”

Ahead of the 2018 election, You Can Vote visited five counties’ jails. They were planning to expand to five more in 2020, including the jail in the state’s most populous county.

But this year is different.

Visitors are not allowed inside correctional facilities this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving voting advocates worried the voting rights for jailed people will become yet another victim of the virus.

Metzguer and Fellman said their organization is pivoting.

Every interested jail will still receive “voter education materials” — posters and signs about voting rights and eligibility that officers can hang up within the facility in advance of any formal training.

But they’re hoping jail partners will allow them to offer “remote training,” including online registration access through iPads, for incarcerated people.

“They still need to be able to learn about their right to vote, get registered, and request an absentee ballot, if that's their choice,” said Fellman. “And the easiest way to do that under COVID is virtually.”

For county jails that do not offer iPads for detainees, You Can Vote is reaching out to see if they can train detention officers to facilitate voting rights education and registration drives instead.

It’s not ideal, said Fellman.

“Having the only people who have access to folks in detention be somebody in a power position over them is hard,” she said. “We have no idea what they're going to say, and we have no idea how it’ll be received from an authority figure who voters may or may not trust.”

Other experts, though acknowledging the health risks additional visitors bring, also expressed reservations about jail staff playing a direct role.

“Correctional officers may exert pressure for them to vote in a certain way,” said Mitchell D. Brown, of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, a Durham-based nonprofit that protects the voting rights of communities of color.

But You Can Vote continues to make new partnerships, even with these added challenges. Sheriff Garry McFadden, whose Mecklenburg County Detention Center houses the largest inmate population in the state, has made it his personal goal to ensure at least 300 people incarcerated inside register to vote.

"We encourage their right to vote and we’re going to continue to do that," said McFadden. "Just because they’re incarcerated doesn’t mean they’re not citizens of our community. If we never strip them of their dignity, we will never have to worry about restoring it."

The Mecklenburg County jail is opening its doors to virtual trainings from You Can Vote throughout the month of September. It’s the first time the jail has done training sessions during a national election year.

Hannah Critchfield covers maternal health and prison health issues for North Carolina Health News. This dispatch is part of a series called “On the Ground” with Report for America, an initiative of The GroundTruth Project. Follow her on Twitter: @HannaCritch

Read the first dispatch: Polygamy, Statehood and the First Woman to Vote

Read the second dispatch: Unlocking the Vote of Connecticut’s Formerly Incarcerated

Read the third dispatch: Overcoming Barriers for Native American Voters

Read the fourth dispatch: The Legacy of Activism in the Motor City

Read the fifth dispatch: How Shifting Demographics Are Changing a 2020 Swing State

Read the sixth dispatch: Getting Out the Latino Vote in Rural California

Read the seventh dispatch: ‘Washed Away by the Majority’

The ratification of the 19th Amendment led to the single greatest expansion of voting rights in the history of the United States. But in the 100 years since its ratification in 1920, millions of American citizens have faced barriers to the vote. In this series of essays, American Experience, in collaboration with the GroundTruth Project’s Report for America initiative, explores the many ways the fight for voting rights continues today. From overcoming felon disenfranchisement in Connecticut, to exposing gerrymandering in Texas, these On the Ground dispatches highlight how Americans continue working to have a voice in the democratic process.