“We rock ‘n’ rollers will resist—and we will triumph!”

When the smoke cleared on Disco Demolition Night, debate over its cultural meaning began.

This article is the seventh in a series called A Thousand Words, where we feature an interesting image from one of our films alongside an essay about why that picture is worth, well, a thousand words.

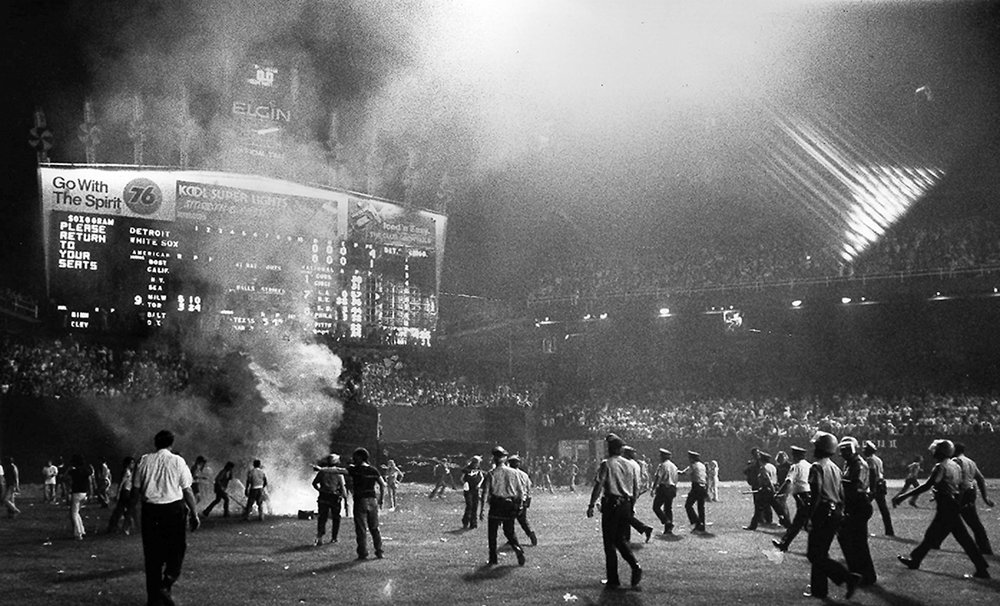

In the bright glare of Comiskey Park’s stadium lights, the rising column of smoke takes on a spectral quality. Riot police approach from the right to close in on the phantom, a smoldering pile of vinyl records, at center field. Debris litters the turf below; haze obscures the deck above. Disco Demolition Night, as captured here by a Chicago Sun-Times staff reporter, had turned into something far more out-of-control than a promotional stunt during a double header.

The July 12, 1979 event was the brainchild of a Chicago shock-jock-style radio personality, 24-year-old Steve Dahl, and Mike Veeck, Chicago White Sox promotions manager and son of the baseball club’s owner. Dahl had become a self-appointed anti-disco activist the previous Christmas Eve when he lost his job; his then-employer had switched overnight from rock to an all-disco playlist, following a nationwide trend that saw many radio stations jump on the disco hype train.

Dahl landed at WLUP 97.9, another rock station, where he developed a loyal following. He opened each morning’s broadcast with a ritual: According to a 2019 interview with NPR, Dahl would first cue up a disco song, and then after a harsh record scratch, play the sound of an explosion. He began hosting “Death to Disco” rallies at local Chicago nightclubs, and his band, Teenage Radiation, recorded a disco parody track (sample lyric: “Look at my hair, it's perfect/I saw Saturday Night Fever/Eighty-seven times”). “We have to destroy all disco, it’s our job,” Dahl told his listeners. He planned to make good on his destructive mission, literally, by blowing up a cache of disco records at a local mall. When Veeck learned of the idea, he offered Dahl a much larger venue for the pyrotechnics. The event would take place on one of Comiskey Park’s teen nights.

Dahl was tapping into an animus that had as much to do with anxiety over the zeitgeist as dislike of a musical genre. “It’s worth remembering now that in 1979, the economy and economic opportunities for people who don’t have a college education is actually shrinking,” Adam Green, a professor of African American history and cultural studies at the University of Chicago, told American Experience. “The city is changing because of things that have to do with the economy and politics; it’s not changing because of disco music. But if Steve Dahl says that he’s been screwed by disco, it gives permission to other people to say, ‘you know what? I’ve been screwed too.’”

Steve Dahl’s band recorded an anti-disco parody of Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy.”

Disco had first emerged earlier in the decade, evolving out of funk, R&B and soul music; its innovators were Black, gay and Latino, and its milieu was the underground nightclub, where those marginalized groups found safe spaces to socialize. However, once record labels realized the genre’s commercial potential, disco music went mass market. And those now-mainstream clubs where disco was played (of which Studio 54 in New York City was the ne plus ultra) developed an elitist cachet that alienated the young, mostly white working class Chicagoans who listened to Dahl. With songs like “Y.M.C.A.,” “Night Fever” and “I Will Survive” topping the Billboard charts, the genre’s ascendance by the end of the Seventies was complete. It was also, then, a prime target for takedown.

These currents were all swirling in the air around the nighttime double header in mid-July, a showdown between the last-in-league Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers. Veeck simply thought Disco Demolition Night would draw several thousand more fans during a losing season.

Dahl wore a combat helmet and fatigues to the park. His anti-disco army turned out en masse, drinking and growing increasingly rowdy as the innings went on. By the time Dahl rode out onto the field in a military Jeep after the first game, nearly 50,000 spectators were crammed into the park; an additional 10,000-plus were outside.

For reduced-price tickets to the park that night, many attendees brought records to be destroyed; all of the sacrificial vinyl filled a bin that was set down, ceremonially, in the middle of the field. Dahl got the crowd chanting “Disco Sucks,” a message matched by homemade banners hung from the stadium’s upper deck. “They’re not gonna shove it down our throats,” he yelled into a microphone. “We rock ‘n’ rollers will resist—and we will triumph!” The records were detonated, tearing a crater into the midfield sod. “That blowed up real good,” Dahl crowed, echoing the signature line that accompanied his on-air disco “explosions.” Triumphant, he got back in the Jeep and rode off the field—along with many of the ballpark security staff. That was when the true mayhem broke out.

People started streaming onto the green by the thousands. They stole bases and tipped over a batting cage; they ripped up turf. They rushed both bullpens and began burning signs. Fights broke out. Veteran White Sox announcer Harry Caray tried to shift the tone by singing ‘Take Me Out to the Ballgame’ over the PA system. No one listened. A message on the scoreboard—PLEASE RETURN TO YOUR SEATS—pleaded, futilely, with the attendees still stoking fires. White Sox announcer Jimmy Piersall opined, “I hope they don’t let you people see what’s going on here at Comiskey Park; one of the saddest sights I’ve ever seen in a ballpark in my life.” Eventually the Chicago riot police arrived, some on horseback, and cleared the field.

Later, after the smoke cleared, and critics and commentators began evaluating the event, many would describe Disco Demolition as an opening salvo in the culture wars. What role racism and homophobia played in Dahl and his groupies’ rebellion remained up for debate. Even from today’s vantage point, a definitive interpretation of Disco Demolition is still murky. “If we seek a true memory,” Green said, “this is the meaning of the backlash against disco, then we're probably going to find ourselves in a situation where we never settle the argument. And I think that that’s the way of all major cultural transformations.”

At American Experience we're always coming across photos from the past that we can't stop thinking about—images that are worth a thousand words.