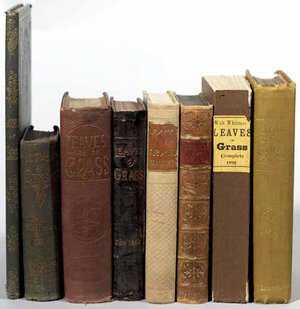

Leaves of Grass is the title of the first book of poems published by Walt Whitman in 1855. It is also the title of the last book of poems published by Whitman before his death in 1892, and of five other editions published during his life. Beginning with twelve poems, each later edition of the book added new poems to the original set, excised others, and edited or gave new titles to previously published poems.

Portrait of an Artist

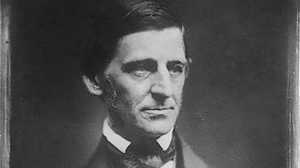

For historians, the evolution of the book through different editions offers evidence of the author's shifting concerns. In fact, Leaves of Grass may be comparable to Rembrandt's dozens of self-portraits over his lifetime — both series reveal the development of an artist over time while each individual work provides a glimpse of one man's concerns at a particular time.

Poet as Everyman

The first edition of the book names no author on its cover or title page. Instead, on the frontispiece, an image of a man in laborer's clothes serves to identify the creator. In the first poem (called in later editions "Poem of Walt Whitman, an American" or just "Walt Whitman" before assuming the title "Song of Myself") the first person narrator eventually reveals himself as "Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos." With its vagueness of authorship, Leaves of Grass embodies the idea of the poet as everyman, a theme reinforced by the inclusive narrator of the verses.

The Second Edition

The initial print run was modest and the book did not sell well. The book did receive a number of rave reviews in New York newspapers — but some were written by Whitman himself. Of more importance was a positive private response from Ralph Waldo Emerson. A second edition of Leaves appeared the next year, 1856, with 20 new poems, as well as Emerson's complimentary letter reprinted in full, and even a quote from Emerson on the book's spine — possibly the first example of "blurbing" in print, even though Emerson never gave his permission for Whitman to use his words. Whitman also included his own anonymous reviews, and other critical responses as well. This version sold just as poorly as the first.

Love and War

Whitman was undeterred. The third edition of Leaves added 146 new poems to the collection, and grouped various works into "clusters." One cluster, "Enfans d'Adam," addressed sensual, procreative love and another, "Calamus," addressed comradeship — the relationship between men. The publishers of the third edition were in Boston and, in a visit there in 1860, Whitman met Emerson. Emerson suggested removing the erotic poetry, but accepted the younger man's decision to keep those verses. Poems with a darker outlook in the third edition reflected Whitman's uneasiness regarding the future of the United States itself in the years leading to the Civil War.

More Editions

Whitman rearranged the poems in the 1867 edition to emphasize themes of social cohesion and unity, relevant in the years of post-war Reconstruction. Whitman had seen the suffering of victims of the Civil War first-hand and with his pen he strove to guide the nation back toward its ideals. The 1872 edition spread these Civil War poems throughout the book, suggesting that the war formed an essential part of the American character.

A Legal Threat

In 1881 Whitman was 62 years old and contemplating his literary legacy in an edition of Leaves that would appear that year. This edition was notable for having a mainstream publisher, James R. Osgood & Co. of Boston, who also published the works of Mark Twain. Osgood sold about 1,500 copies of the book before it was withdrawn following a district attorney's threat to prosecute for obscenity. A Philadelphia-based publisher stepped in and sold more than 6,000 copies, probably in part due to the publicity generated by the legal threat.

"At Last Complete"

The last version of Leaves of Grass to appear in Whitman's lifetime contained just minor corrections to the 1882 edition, with new poems bound into the book as annexes, and not as part of Leaves proper. Whitman wrote to a friend: "L. of G. at last complete — after 33 y'rs of hackling at it, all times & moods of my life, fair weather & foul, all parts of the land, and peace & war, young & old — the wonder to me that I have carried it on to accomplish as essentially as it is, tho' I see well enough its numerous deficiencies & faults."

The final arrangement of the poems suggests birth, adolescence, maturity and decline; in short, the chronology of a life. Still widely read today, it serves as an autobiography of sorts, recording some of the most tumultuous decades of American history.