In these interview excerpts from scholars, explore Whitman's calling as a poet, and the idea of a national poet.

Whitman's calling as a National Poet:

Allan Gurganus, an American writer whose works include the novels Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All and Plays Well With Others: I think Walt Whitman went to the help wanted section and found a squib that said Wanted: National Poet. And he was innocent enough to believe there really was such a job. And he was innocent enough to believe that if he could just write a poem that incorporated everything he felt and suspected and hoped for from America, that he would have the position. And you know, by God, he did it.

Ed Folsom, a literature professor and Whitman specialist at the University of Iowa: He grows up in the first generation of people that are thinking of America, the United States, as a country ... these are the people who, as they grow up, begin to ask the questions about what is an American literature going to be like...

I am, Whitman would say, a native American. And so many of the writers in Whitman's generation became obsessed, really, with the ideal of what an American literature would be. It would have to be new. It would have to be different. It would have to define itself against British literature. It would have to claim an American language instead of an English language. And that American language would be a looser language than British English. It would have fewer rules. It would be more promiscuous in the sense that it would it would absorb words from lots of other cultures because it would celebrate the immigrant culture in America and part of the celebration of the immigrant culture would be the growing diction as, as European words and African words and Native American words all entered into American English.

Betsy Erkkila, a literature professor at Northwestern University: He wants to sell [Leaves of Grass]. He's hoping that it's going to reach the American people. He's finally found his form, what he's going to do and he thinks that he's going to sell numbers of volumes of poems throughout the country to people at all levels of society — especially, probably, to the working class — and he will become a beloved national poet and, and a poet who's also very actively involved in the struggle for democracy and who has finally chosen that his way of struggling for that vision will be through the realm of poetry.

Whitman's vision of America:

Allan Gurganus: It's so unlikely a person without sponsorship, a person who, to use the terminology of the 19th century, was friendless, an orphan in the artistic world, to have presented this vision of America that somehow coincided sexually, professionally, linguistically, philosophically with everything other people were hoping for, that would somehow match them and stir them and inspire them and include them.

Ed Folsom: As Whitman grew up during the first half of the 19th century, [there was a] sense of what the United States was going to be — not only politically, as an actual entity, but what it was going to be creatively, imaginatively — as a nation producing its own literature.... Many people were concerned, as Whitman was, growing up, with the idea of America producing its own epic, because the epic poem became sort of a marker of a realized, fully realized, culture. Whitman, in writing Song of Myself, I think, was imaging an American epic. What would an American epic be like? And the first thing... is that it would celebrate the American self, the I.

Poetry and national unity:

Kenneth Price, an American literature professor and Whitman specialist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln: ...When Whitman returns to New York after the trip to New Orleans it is for him a death of politics as he'd known it before. I think he has given up on trying to reform the nation through writing editorials... somehow, something more profound is necessary. And he needs to address the soul. He needs to address the psyche. He needs to address something that will serve to create a genuine sense of community in a nation that's clearly fracturing before his eyes.

Karen Karbiener is a Whitman scholar who teaches at New York University: There's a tremendous amount of confidence... in the 1855 edition [of Leaves of Grass]. But, especially in the preface, you also see a lot of fear, and a bit of anxiety about trying to get this message across. The United States needs poets, he says. He knows somebody has to save the nation....

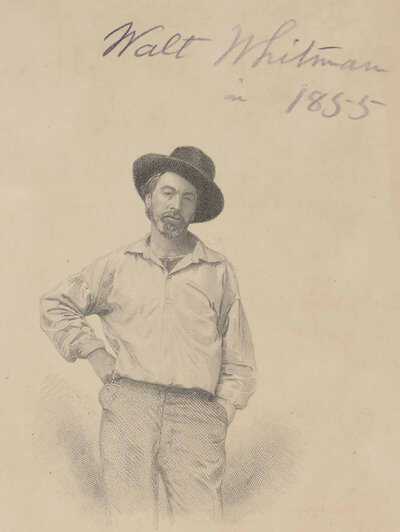

... this book could be written by anybody and really was written for everybody. I think casting the book out there, not putting his name on the title page or even on the cover, made it into everybody's book. It's the lowest common denominator with Whitman to always say his ego propelled this forward. But remember, he really wanted this book to be written by the nation, for the nation. There's no authorship on here and he really does look like an everyman on that frontispiece. So maybe he thought that the book could be propelled forward because it, it was necessary, the nation was writing this book.

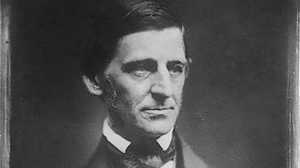

David Reynolds, a professor at the Ph.D. Program in English at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York: He constantly says in that preface, the poet is the one in balance. The one truth true, to whom all things flow and are equalized. The poet is the equalizer of his age and his land. He is his age transfigured. His age transfigured.

He really, really has a national mission and a personal mission to advance himself, not necessarily as just a private person, but as someone who can kind of see all sides of experience, of American experience and of world experience and allow all these things to kind of come together in a loving center. And this is what makes the 1855 edition so distinctive...

Ed Folsom: I think that Whitman believed that Leaves of Grass was going to prevent a civil war. I think he had that much faith in the 1860 Leaves of Grass. Leaves of Grassin the 1855 and '56, and '60 editions are really a book about preserving the Union. It's a book about holding things together. It's a book about being able to absorb contradictions and still maintain a single identity. And that single identity is an individual identity, but it's also a national identity. And he wants that individual identity that's large, and contradicts itself, and contains multitudes, to be the representative self for a country that was facing all kinds of division and needed to learn to accept contradictions.