The Star-Spangled Banner during Times of War

By Carolyn MacLeod

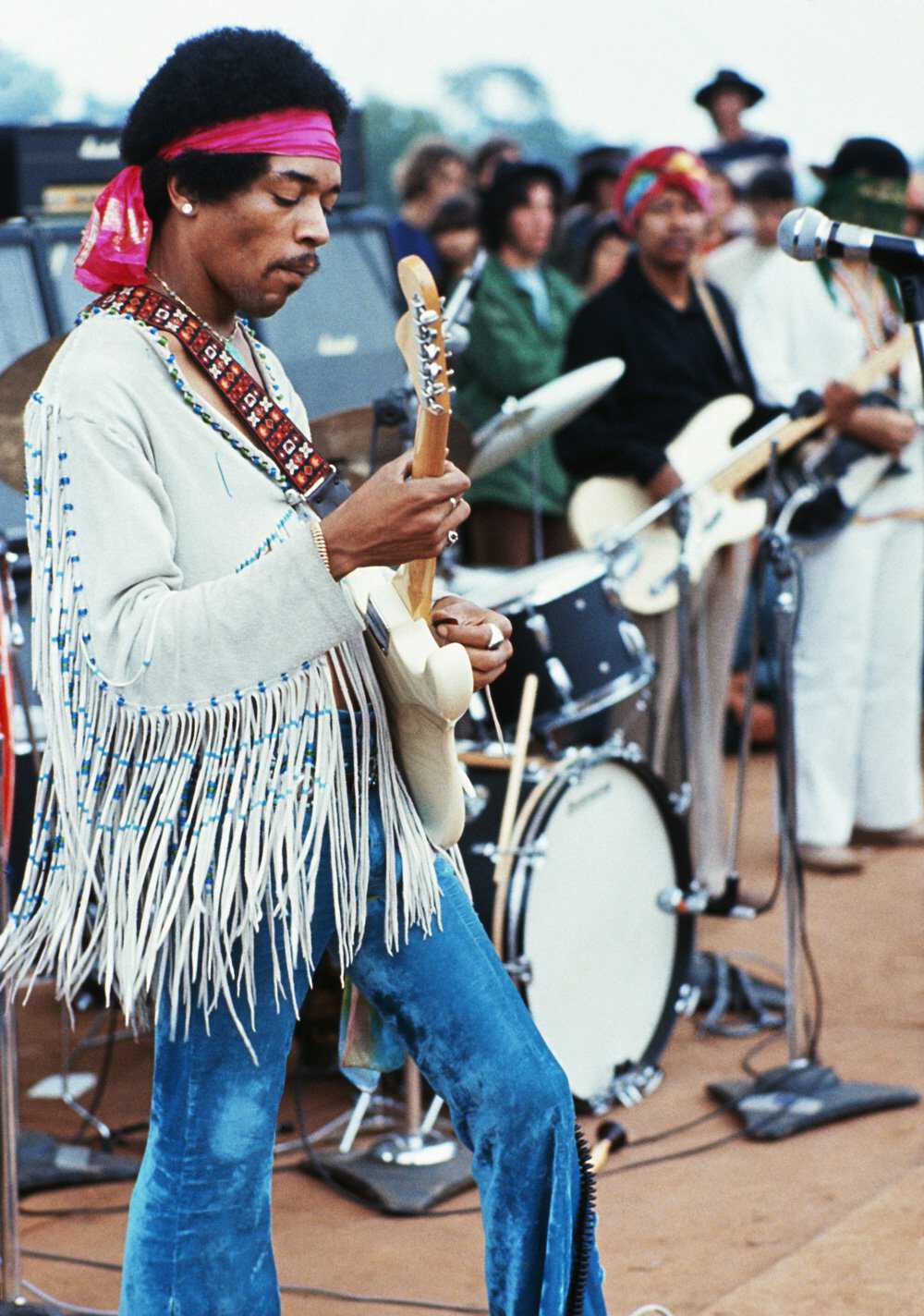

By the time Jimi Hendrix took the stage at Woodstock around 9 a.m. on Monday, August 18, 1969, many of the festivalgoers had already left. Those that stayed were witness to one of the most iconic performances at the Music and Art Festival: his “Star-Spangled Banner.”

“I was backstage writing up some notes,” recalled journalist Bernard Collier in Woodstock: Three Days that Defined a Generation. “Suddenly into my head stabbed this sound. It sounded exactly like rockets, missiles and bombs bursting in air. I’d never heard anything like that in my life.”

It’s difficult today to separate this performance from the summer of 1969, and thanks to the Academy Award-winning 1970 documentary Woodstock, the performance has become emblematic of the experience of Woodstock itself. At the time, however, Hendrix’s performance came across as startling and utterly new.

“I remember people literally tearing their hair out,” said Woodstock director, Michael Wadleigh. "I looked out with one eye and I saw people grabbing their heads, so ecstatic, so stunned and moved, a lot of people holding their breath, including me. No one had ever heard that. It caught all of us by surprise.”

Hendrix wasn’t the first musician in the 20th century to surprise and disturb audiences with an artistic re-interpretation of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Before him, José Feliciano in 1968 and Igor Stravinsky in 1944 also gave audiences hitherto unheard experiences of the national anthem. Their interpretations invited controversy, but each artist saw his performance as a patriotic act. Hendrix in his performance did something further that had not been accomplished previously, not even by the original. In performing the anthem with his psychedelic take on the blues, Hendrix brought the lyrics to life and in doing so transformed the national anthem into a commentary on American ideals in a time of war.

Woodstock promised three days of peace, love and music during the turmoil of the Vietnam War and racial unrest of the civil rights movement. Through the screen of drugs and utopianism, these realities were evident, nonetheless. The political climate was reflected in music throughout the festival, from Richie Haven’s “Freedom” in the opening performance of the festival, to Joan Baez’s renditions of “Joe Hill” and “We Shall Overcome,” to Country Joe McDonald’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die Rag,” to Jefferson Airplane’s “Uncle Sam Blues,” to The Who’s “My Generation.”

Three days bled into four and Hendrix began to play "The Star-Spangled Banner" that Monday morning, as the festival drew to a close.

“We’re at the most peaceful gathering that was probably happening on the planet at the time. And he hooked us up with Vietnam,” said Tom Law, a member of the Hog Farm commune who was present that morning. “It was the devastation and the brutality and the insanity. That was a quintessential piece of art.”

Three weeks later, on September 9, 1969, Jimi Hendrix walked onto the set of the Dick Cavett Show. Cavett soon turned the conversation to Hendrix’s Woodstock set. “What was the controversy about the national anthem and the way you played it?”

“I don’t know man,” said Hendrix. “All I did was play it. I’m American, so I played it. I used to sing it in school, they made me sing it in school so — it was a flashback, you know.”

Over the audience’s laughter at Hendrix’s cool response, Cavett joked, “This man was the 101st airborne, so when you write your nasty letters in…”

A puzzled look bloomed on Hendrix’s face. “Nasty letters?”

“Well, when you mention the national anthem and talk about playing it in an unorthodox way,” Cavett explained, “you immediately get a guaranteed percentage of hate mail from people — “

“That’s not unorthodox,” Hendrix interrupted. “That’s not unorthodox.”

“It isn’t unorthodox?”

“No. No, no. I thought it was beautiful. But there you go.”

In January of 1944, at the height of World War II and 25 years before Woodstock, Igor Stravinsky prepared to conduct his "Star-Spangled Banner" with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

In his arrangement, Stravinsky hoped to address an issue that has plagued the song since its earliest days: its tonal range. The distance from the lowest to the highest pitch in “The Star Spangled Banner” is twelve notes, or an octave and a half, making it unusually challenging to sing. Compare that with other countries’ anthems: England’s “God Save the Queen” has a range of seven notes, while France’s “La Marseillaise” and Canada’s “O Canada” each span nine. When congress was debating adoption of the song as the national anthem, singability was a chief concern. As much as Stravinsky sought to solve these problems, however, his miscalculated efforts and the war-time climate surrounding his performance led to uproar.

Stravinsky’s "Star-Spangled Banner" challenges listeners’ expectations subtly. Instead of the bouncy rhythm heard at the beginning of phrases, his rhythm is regimented and metered, like “a church hymn,” as Stravinsky put it. Especially off-putting may have been Stravinsky’s use of dissonance in the closing line “O’er the land of the free…,” with a dominant seventh undercutting the triumphant final phrases. According to the Associated Press review of the concert, Stravinksy’s effort to make the national anthem easier to sing along to failed: “[T]he odd, somewhat dissonant harmonies of the sixty-one-year-old composer’s arrangement became evident. Eyebrows lifted, voices faltered, and before the close practically [everyone] gave up even trying to accompany the score.”

The negative press apparently spurred the Boston Police to confront the composer before his second performance. An obscure Massachusetts law prohibited playing the national anthem as part of a medley, with embellishment or as dance music. Stravinsky agreed to remove his arrangement of the anthem from the program.

A Russian-born immigrant to the U.S., Stravinsky defended his interpretation of “The Star-Spangled Banner”: “It was my desire to do my bit in these grievous times toward fostering and preserving the spirit of patriotism in this country.” He became a naturalized U.S. citizen the following year.

Ten months before Woodstock, 23-year-old José Feliciano walked onto center field at Detroit’s Tiger Stadium to sing the national anthem at game five of the 1968 World Series. Feliciano, a Puerto Rican-born, crossover sensation, had recently won two Grammy Awards following the enormous popularity of his cover of the Doors’ “Light My Fire." But his interpretation of “The Star-Spangled Banner” was about to bring his career close to a screeching halt.

It was the fall of the year when American deaths in Vietnam reached their peak. Congress recently passed the Flag Protection Act of 1968, criminalizing the desecration of the American flag. On October 7, 1968, when Feliciano began to play, the tune on his guitar didn’t immediately sound like the national anthem. As he sang, listeners heard the national anthem as folk song. It sounded more like Bob Dylan than Francis Scott Key.

Amid the claps, also rose the unmistakable sound of boos. Irate calls flooded the stadium switch board and NBC, the network broadcasting the game. RCA Records released a recording of the performance as a single, which eventually peaked at number 50. Many commercial stations refused to play Feliciano’s music—this song or any other.

“When I did the anthem, I did it with the understanding in my heart and mind that I did it because I’m a patriot. I was trying to be a grateful patriot,” Feliciano later recalled. “I was expressing my feelings for America when I did the anthem my way instead of just singing it with an orchestra.”

Stravinsky attempted to make the national anthem more accessible but instead alienated his audience with his modernist approach and drew an intervention by police. Feliciano’s folk interpretation of the “Star-Spangled Banner” repelled some fans, who were offended by what he brought to the anthem. History has been kindest to Hendrix's interpretation, perhaps because of what he brought to the song. Hendrix put his psychedelic blues in service of a classic songwriting technique called "text painting," sometimes known as "word painting." This is where the music directly reflects the content of the lyrics. Hendrix brought the words of “The Star-Spangled Banner” to life by reflecting not just what they might have meant when they were written in 1814 but by reflecting the meaning they might take on for Hendrix and his audience in 1969.

Text painting can be heard throughout music history, from Gregorian chants that would employ rising melodies to accompany words describing Jesus’ ascension to heaven, to Johnny Cash’s chorus of “Ring of Fire” going steadily “down, down, down.” This connection between music and lyrics doesn’t exist in Key’s version of "The Star-Spangled Banner" but does in Hendrix’s performance.

Key’s lyrics are a patriotic description of a post-battle scene, but the words have very little to do with the music underscoring them — perhaps because they were composed nearly 40 years, an ocean and multiple wars apart. The music was composed by John Stafford Smith in 1775 as the song “To Anacreon in Heaven.” Smith was a young church musician in London who was commissioned by the Anacreontic Society, a gentlemen’s amateur music club, to compose the music for their club’s “constitutional song.” The lyrics to that version, written by Society president Ralph Tomlinson, eulogize the Greek poet Anacreon and his favorite themes: the very rock and roll topics of wine, women and music.

Francis Scott Key composed the poem following the Battle of Fort McHenry in 1814. Key, a respected lawyer and amateur poet, was sent to negotiate the return of a physician captured after the British marched through Washington D.C. and burned the White House and Capitol. From the Chesapeake Bay, where he secured the physician’s release, Key watched the sun rise on September 14, over the fort and its flag still waving after British bombardment. Key’s poem was then set to Smith’s music — an existing melody that doesn’t particularly correspond with the feeling or imagery of his words.

Hendrix, on the other hand, used text painting to powerful effect. His version is entirely instrumental, but he capitalized on his audience’s knowledge of the lyrics by emphasizing their meaning through sound. Notably, Hendrix played the entirety of the vocal melody — but punctuated the phrases with ornamental improvisations.

Hendrix begins the song fairly closely to the traditional vocal melody, adding a few melismatic flourishes and sustained notes, but tracking the first four lines of the eight-line song. Meanwhile, a snare drum taps out a tight rhythm, recalling a military drum line.

When Hendrix arrives at “And the rocket’s red glare,” the song begins to tip over. Using distortion pedals, he creates chorus effects and sends notes echoing into higher octaves — the sound of rockets soaring and bombs bursting over-head. The percussion follows suit and breaks from its regimented rhythm to join the guitar voice in a jazz-like cacophony. The guitar soars from the highs to lows as a deep grumbling creeps in, courtesy of Hendrix’s fuzz pedal. The melody returns with “the bombs bursting in air” before a siren-like wail deconstructs the tune once more. Then a descending slide from high to low notes sounds like a dive-bombing plane. Just when Hendrix is at his most discordant, his guitar seems to wail with human cries of anguish, and he returns to the melody at the song’s narrative climax of “Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.”

Before going into the song’s final couplet, Hendrix takes his version of Key’s war story and extends it to a moment outside the narrative frame of the song with a musical allusion to “Taps,” the bugle call played at military funerals and here a raw reminder of the cost of war. He completes the penultimate line, “O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave,” letting the last note sustain and distort and tremble before continuing. On “O’er the land of the free” in the final line — he sustains the highest note, resounding for a moment, before the song ends and the distortion returns as a soft echo of the sounds that came before.

Hendrix infused the song with an experience of war up close — not with the glory of war nor the heartbreak of those at home, but as a sonic record of the overwhelming terror of battle as it was known then in 1969. He took the 155-year-old song and made it into an expression of lived experiences in his present-day America.

With his performance of the anthem, Hendrix joined the company of a Puerto Rican pop star and an immigrant modernist composer in a patriotism that embraces national ideals while making room for diverse cultures and experiences, even in a time war.

Hendrix refracted the militaristic “Star-Spangled Banner” text through his psychedelic re-invention of the African America blues tradition. It was unorthodox, beautiful and utterly American.

Carolyn MacLeod is the Audience Engagement Editor at American Experience. Carolyn holds degrees in music education from James Madison University and Arts Administration from Boston University. In her free time, she writes about arts appreciation for a number of Boston-based online publications.

Published July 30, 2019.