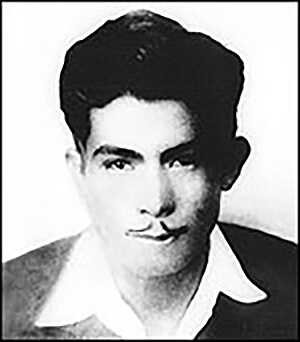

José Gallardo Díaz (1919-1942)

José Díaz, a 22-year-old farmworker, was murdered on his way home from a neighbor's birthday party early on the morning of August 2, 1942. In the years to come, the details of his life would be largely forgotten to all except his family. The Los Angeles police used his murder to launch a widespread attack on what they perceived as an unruly and rapidly multiplying Mexican American youth "element." The press would identify José and his assailants as gang members whose violent behavior substantiated the belief that Mexican American kids were enemies in society's midst. The murder trial would be driven by the L.A. authorities' desire to teach Mexican Americans a lesson instead of delivering impartial justice in the case.

On December 9, 1919, José Díaz was born to Teodolo Díaz and Panfila Gallardo Díaz in the small town of Durango, Mexico. Just four years later, the Díaz family fled drought, famine, and the volatile aftermath of the Mexican Revolution. They joined millions of refugees who were fleeing northward to seek a better life. By 1928 the family had settled just outside the city of Los Angeles. Their new home was relatively isolated from the bustling and rapidly changing city. They lived in a bunkhouse, one of many arranged in a cluster delegated for ranch hands. The Williams ranch was like many others: a small, but well-connected community where immigrant families settled and built their lives. Close-knit social networks developed within these communities so that the same families and friends attended birthday parties, weddings, and funerals.

Given the mobility and labor involved with farmwork, most farmworkers' children did not finish high school. José Díaz left school after the 8th grade and quickly got a job at the Sunny Sally Packing Plant, where his brother and sister also worked packing vegetables. Soccorro and Lino Díaz both described their brother as quiet, reserved, and conservative for his age. As was the custom in their family, José obediently gave his earnings from vegetable packing to his mother to help support the household.

José Díaz did, however, join with other Mexican Americans of his generation in enjoying jazz culture. His sister Soccorro remembered him sporting the white shirt and pegged pants that were part of the controversial "zoot suit" to attend weekend parties and dances. Many on the ranch spent the hot summer months swimming at the local reservoir that was used for farm irrigation. The place was a preferred hangout for boys and their girlfriends, dubbing it the "Sleepy Lagoon" after a popular ballad of the day.

Díaz was also caught up in the excitement surrounding the United States' entry into World War II. By the summer of 1942, the 22-year-old José Díaz enlisted in the U.S. Army, causing his mother anxiety. For him, serving in the army was a much-anticipated opportunity. The weekend before he was to leave, his mother sent him to have his picture taken, the first he ever had. In the picture, he is dressed neatly, with hair well-combed, looking young and ambitious. That same weekend, he was to attend a neighbor's birthday party. His murder on the way home from that party, on the day before he was to report to the army, makes his first and only picture particularly poignant.

As the party that Saturday night neared, José Díaz told his mother he didn't feel like going. At the last minute, he changed his mind. The party was for Eleanor Delgadillo Coronado, and it was held at her parents' home, not far from the Sleepy Lagoon. Near 1 a.m. the party began to break up. Eleanor Delgadillo later said she saw Díaz leaving with two boys named Luís "Cito" Vargas and Andrew Torres. Ten to twenty minutes later, a group of kids from the 38th Street neighborhood arrived at the party, seeking revenge for an earlier beating of some of their friends. Among them was Hank Leyvas, the young man who would later be sentenced to life imprisonment for Díaz's murder. The ensuing melée would leave many wounded. José Díaz was found later that morning lying face up in the middle of the road. He was barely breathing, bleeding heavily, and his pockets were turned inside out.

Lino Díaz, José's younger brother, was home at the time. Once told about his brother's condition he rushed him to the Los Angeles County General Hospital. José Díaz died soon after arriving. His death certificate stated the immediate cause of death was the result of a contusion of the brain and a subdural hemorrhage due to a basal fracture of the skull. At the murder trial in October, Dr. Henry Cuneo, the admitting physician and surgeon at the hospital, stated that José had suffered from a cerebral concussion. His face was cut and swollen and he was bleeding from inside his left ear. He had been stabbed twice and a finger on his left hand was broken. Dr. Cuneo confirmed that José never regained consciousness.

As these events transpired, José Díaz's father and younger siblings were up north picking prunes. Because Soccorro Díaz became ill, the family decided to return home early. Neighbors notified them of José's death immediately upon their arrival.

José Díaz's family would never believe that he received justice. Aside from being called a gang member, Díaz was an obscure figure throughout the three-month-long, mass trial presided over by Judge Charles W. Fricke that eventually sentenced 17 young men to prison and sent their girlfriends to reform school. The two young men with whom Díaz was spotted leaving the party were never questioned. Even when the defendants were freed from prison in 1944, on grounds that they had received an unfair trial, the case was never reopened. The murder at the Sleepy Lagoon remains officially unsolved.

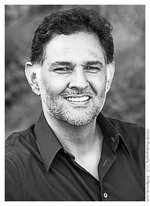

Dr. Eduardo Obregón Pagán is the Bob Stump Endowed Professor of History at Arizona State University, and Associate Dean of Barrett, The Honors College. He is the author of Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon: Zoot Suits, Race, and Riot in Wartime L.A. (University of North Carolina Press, 2004), and Valley of the Guns: The Pleasant Valley War and the Trauma of Violence (University of Oklahoma Press, 2018). He was a co-host on the popular PBS series History Detectives, and is an adjunct curator of history at the Desert Caballeros Western Museum.