How Bleacher Seats Demolished a Barrio

Chavez Ravine was a thriving Mexican-American community—until L.A. needed a place to put Dodger Stadium.

Even in the best of times, residents of Los Angeles looked upon Chavez Ravine as a problem to be solved.

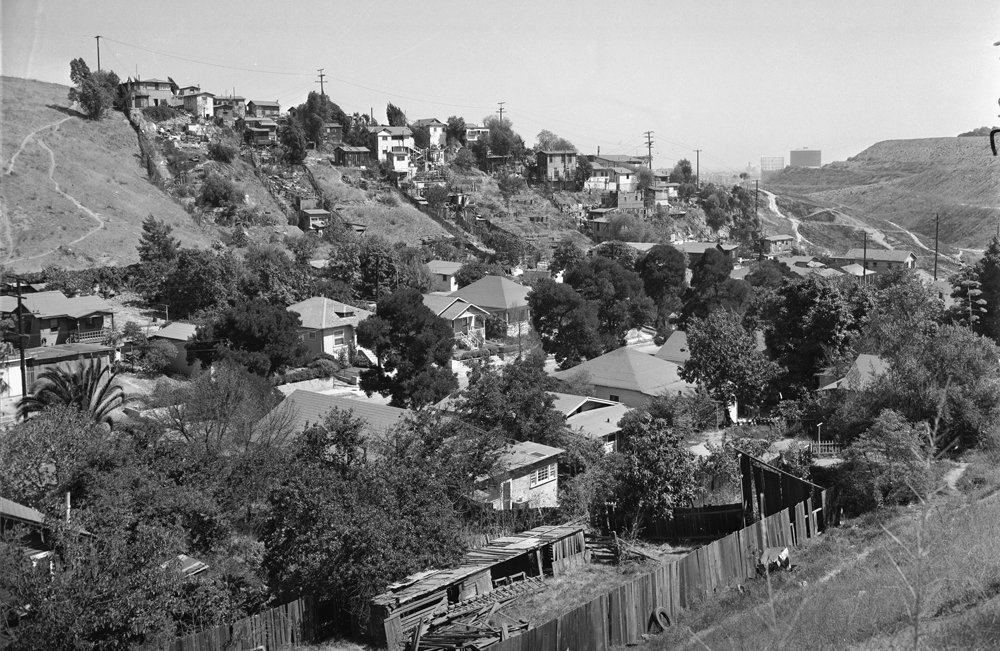

Chavez Ravine was a picturesque area of hills and valleys just a few miles to the north of the business sector of Los Angeles. That location, and its visibility from the downtown, was both a blessing and a curse for the people who lived there.

For most of the 19th century, Chavez Ravine existed simply as one of the many undeveloped tracts of land that surrounded Los Angeles. As a new century dawned, the city began to rapidly expand and develop into a metropolis, embracing all of the conveniences of urban life that the 20th century offered: high-rise office apartments and office buildings, paved streets, electricity, street lights and street cars.

But no such investments were made to Chavez Ravine. It remained rural and unincorporated next to a growing, modernizing urban center. The residents of Chavez Ravine were mostly content with the bucolic nature of their small village. The area lacked basic city services, for sure, but the residents were closely connected and self-sufficient. Their homes were sound, the air was clean and they grew much of their own food. Children could play freely in the hills.

But city residents tended not to look upon that rural community with the same grace. To their eyes, it was little more than a shantytown within sight of City Hall. Something had to be done.

Two unrelated postwar developments far to the East would forever change Chavez Ravine. The first was a bill passed by Congress appropriating funds for municipalities to create low-income public housing. The second was a disagreement between an architect and the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers over a parking lot.

Civic leaders eagerly campaigned for federal funds in a bid to reinvent the unincorporated areas of Los Angeles. Residents of Chavez Ravine were notified that they had to sell their homes to make way for the planned Elysian Park Heights public housing development. Some refused to leave, but many saw no choice other than to sell at below-market prices. Residents were promised that they would have first pick of a new home, in new modern neighborhoods with city services.

Private investors, however, had different designs for Chavez Ravine, and the political winds of the postwar era changed public support for public housing. Brooklyn Dodgers majority owner Walter O’Malley was very unhappy with plans for a new stadium in Brooklyn. Los Angeles investors were eagerly looking to land a major sports franchise for the city. They saw real potential in coaxing O’Malley to move the Dodgers to Los Angeles. To sweeten the deal, they offered the Chavez Ravine as the perfect spot for O’Malley to have the stadium built exactly as he wanted. They only had to secure the support of Los Angeles residents, and clear out the remaining homeowners in the ravine.

By that time, a new mayor and city council no longer supported the public housing project, fearing that it was too communist in a political climate shaped by McCarthyism. The citizens of Los Angeles approved the deal in a referendum to accept the stadium over the housing project, with the help of prominent actors who campaigned for their votes.

The remaining residents of Chavez Ravine held out hope that they could prevail in preserving their homes through community action. But in the end, Sheriff's deputies descended on the holdouts on eviction day and forcibly removed the remaining residents from their homes. Bulldozers then moved upon the land, destroying all traces of the neighborhoods that once thrived in Chavez Ravine.

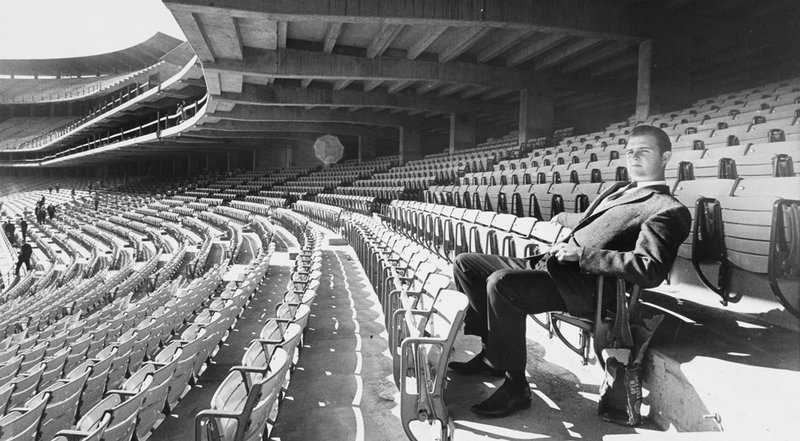

Dodger Stadium arose over the ruins of a once thriving community, a triumph of urban development and the visions of the powerful and wealthy. The families of Chavez Ravine who fought to protect their homes were never compensated for the destruction of their property. For those who complied and sold their homes, the promises the city made of new housing never materialized.

Julian Chavez arrived from New Mexico in the 1830s and became a civic leader in early Los Angeles. He eventually purchased the hilly land known as the Stone Quarry Hills just a few miles north of the city center. Over its history, it was known as Chavez Canyon and then Chavez Ravine. The land served as a refuge during the smallpox epidemics, as the location of L.A.’s earliest Jewish cemetery, and later a refuge for people who were not allowed to purchase homes in the racially-restricted, white only neighborhoods. In time, three neighborhoods arose in Chavez Ravine: Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop.

By the early 20th century, Chavez Ravine had developed into a semi-isolated community, but one that was tightly-knit and self-sufficient. It was once described as a “poor man’s Shangri La.” Residents grew their own food and raised chickens, goats, pigs, and even peacocks in the open land. Generations of families celebrated weddings and baptisms, and held funerals in a neighborhood Catholic church. The elementary school hosted dances and cultural events, and published a bilingual newspaper for the community. But basic city services did not extend to Chavez Ravine. Most of the roads were packed dirt without streetlights, and many homes lacked indoor plumbing.

The local grocery in Chavez Ravine was one of the ways in which it developed self-sufficiency. The store stocked many items that were grown and produced in the community, and fostered a local economy of goods and services. Residents also found ways around the lack of basic city services. An iceman made regular deliveries of large blocks to this grocery story and to residents in order to keep food refrigerated. Despite the shortcomings of the area, residents still took pride in their appearance and kept themselves clean and well dressed.

Councilman John Roden led a delegation from Chavez Ravine to present a petition with 2,100 signatures to the board of public works, asking the city to provide more bus lines to the area. The residents of Chavez Ravine, Roden explained, had been walking for years to the nearest streetcar lines that were at least a mile away, sometimes farther. Representatives of the United States Navy also supported this request for new bus lines because naval personnel had to walk in and out of the area every day to reach the armory that was also built in Chavez Ravine.

Italian-American artist Leo Politi moved to Los Angeles in 1931, and for him, the Chavez Ravine was “a happy community where everyone knew and helped one another. At night there were lighted bonfires, and people gathered around and sang songs... In many ways, Chavez Ravine was living a life all its own. Horse drawn plows were still in use, and the hillsides were planted with corn and sugar cane... Though all this reminded one of a village in Mexico, nonetheless this was old Los Angeles with a charm all its own, a Los Angeles we will never see again.”

Not all residents of Chavez Ravine were Mexican American. Several families moved there because housing was affordable, and the rural nature of the community was appealing. Others appreciated the feel of Old California within a short distance from a modern city. Religious processions through the streets during the holy days were a regular part of community that brought residents together through pageantry, color, and song. Children played together in the streets and in the surrounding hills. Trash was often burned on weekends, and teenagers would gather together to laugh, play instruments, and sing.

With the flood of veterans starting new families after the war, Congress passed the Taft-Ellender-Wagner “Housing Act of 1948” to underwrite public housing developments. Los Angeles officials sought federal funding to renovate different parts of the city, and Chavez Ravine was one of the areas selected for development. In 1950, the city began condemning some properties and sending notices to other residents of Chavez Ravine that they would have to sell their homes to make way for a planned mixed-housing community with playgrounds and new schools. Residents were promised first choice in the new housing. While many sold their homes, others refused to move, citing their right to private property.

For some of the residents who fought the development plans of Chavez Ravine, the issue was whether their right to be secure on their own property prevailed over the plans of the powerful. For others, it was about preserving the distinctive community that had existed since the territorial days.

By 1957, Chavez Ravine looked like a ghost town. About 20 families remained, but they were not alone in their fight to preserve their neighborhoods. Activists from all walks of life throughout Los Angeles gathered to create the City Center Improvement Association. Members began a broad-based campaign of gathering petitions, picketing city offices, and writing letters to city officials. Many activists, mostly women, flooded city council hearings and planning meetings and spoke of housing discrimination, of their long work to own their own homes, and invoked the patriotic sacrifices they and their families made in support of the war.

Los Angeles County Sheriff deputies moved in on the remaining families on the day that came to be known as “Black Friday,” May 9, 1959. No one was spared, and some did not go quietly. Deemed squatters on their own land, the elderly, children, and mothers were handcuffed and carried away in squad cars. All but a few personal belongings were left behind.

With the last remaining families taken away, bulldozers moved in and began flattening the homes of Chavez Ravine. Many still had their possession inside. By the day’s end, the once-thriving neighborhoods of Chavez Ravine were no more. After the sheriffs and wrecking crews departed, some of the residents returned to pick through the rubble to try to salvage what they could of their belongings.

The rise of Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles was a triumph of private-public partnerships and urban planning and renewal. But generations of players and baseball fans who used Dodger Stadium never knew, or perhaps did not care to know, that a thriving community once stood where the stadium is now. Those residents loved their homes and fought valiantly to preserve them. For those who do know the history of Chavez Ravine, Dodger Stadium also stands as a monument to the power of wealth over the impoverished, of the racism inherent to urban renewal, and of the injustices to the families of Chavez Ravine who were never compensated for their losses.

Dr. Eduardo Obregón Pagán is the Bob Stump Endowed Professor of History at Arizona State University, and Associate Dean of Barrett, The Honors College. He is the author of Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon: Zoot Suits, Race, and Riot in Wartime L.A. (University of North Carolina Press, 2004), and Valley of the Guns: The Pleasant Valley War and the Trauma of Violence (University of Oklahoma Press, 2018). He was a co-host on the popular PBS series History Detectives, and is an adjunct curator of history at the Desert Caballeros Western Museum.

Explore our new collection featuring a selection of films documenting the U.S. Latino Experience — along with articles and original features exploring America’s continued struggle with democracy, inclusion and justice for Hispanics and Latinos, and celebrating their contributions to the American story.

Explore nuestra nueva colección: una selección de películas que, documentan experiencias latinas en los Estados Unidos, junto con artículos y videos originales que exploran la lucha continua de los Estados Unidos por la democracia, la inclusión y la justicia de los latinos y que, celebran sus aportes a la historia del país.