Zora Neale Hurston, In Her Element

When the famed writer went to Florida to capture the sounds of the South.

This article is the second in a series called A Thousand Words, where we feature an interesting image from one of our films alongside an essay about why that picture is worth, well, a thousand words.

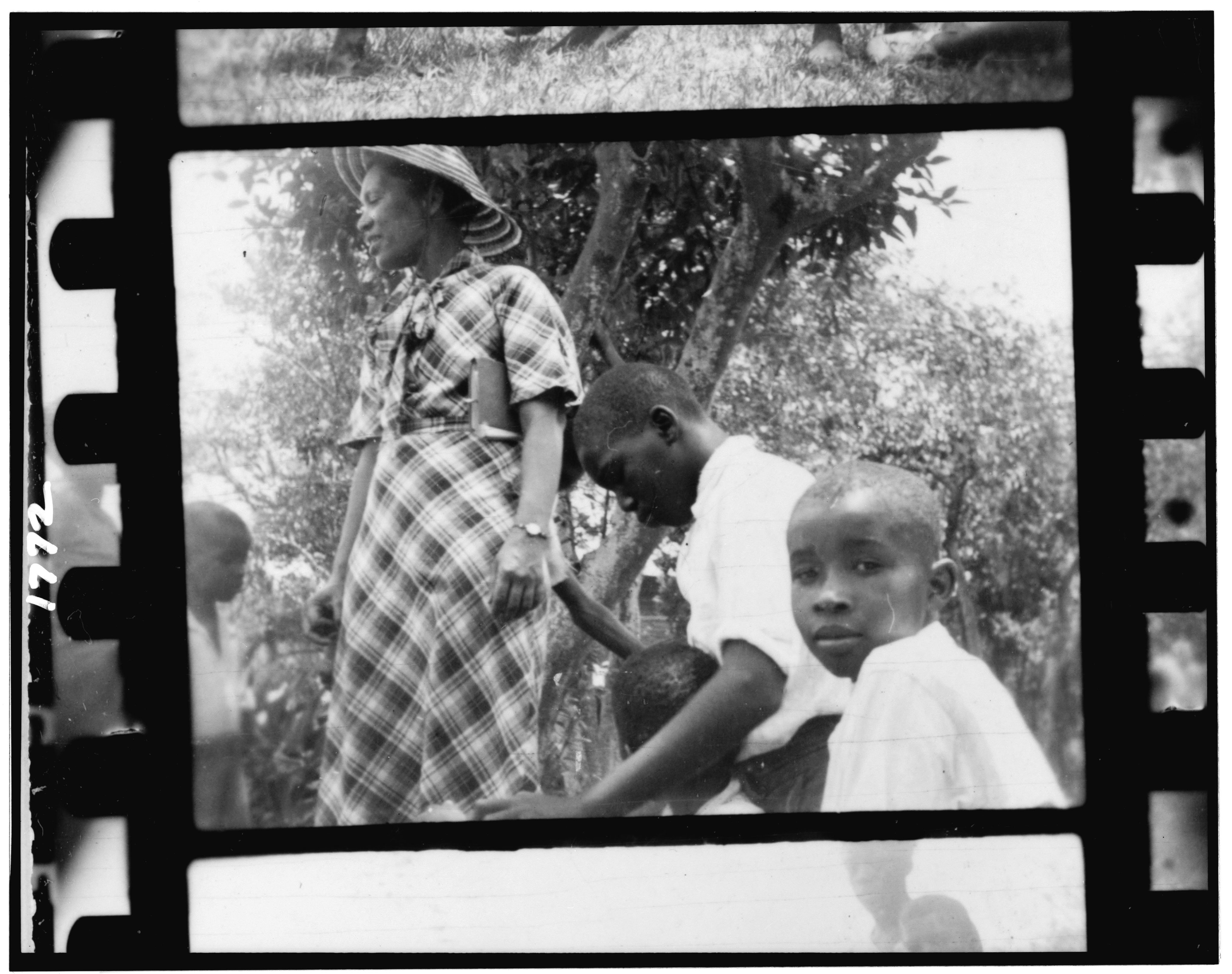

She is nattily attired in a plaid dress, short-sleeved to breathe in the humid Florida heat. She might be on her way to church, or perhaps shopping—but what looks at first glance like a pocketbook tucked under one arm is actually a journal, pen wedged in its pages and ready for her to go to work. Her assignment is to document the assembled children: the games they play, jokes they tell, songs they sing. The boy in the foreground knows that both the notebook and the camera whose lens he looks into are there to record him—but his expression suggests he trusts both, because of her. He can trust her, because she is home.

When the acclaimed Harlem Renaissance author went to Eatonville, Florida in June 1935, she went as a native—Eatonville, Hurston says plainly and proudly in the opening lines of her 1942 autobiography Dust Tracks on a Road, is “where I came from.” But she also returned as the lauded writer and professional ethnographer she had become since leaving. As an undergraduate at Barnard College and doctoral student at Columbia University, Hurston had trained with the foremost experts in the field of anthropology. Now, with this homecoming, she meant to capture her own community’s culture for posterity; to document, as she would call it in Dust Tracks, “our own unbelievable originality.”

Hurston was serving as guide to two researchers who sought her out for a collecting expedition of African American folklore. Alan Lomax was assistant-in-charge of the Archive of American Folk-Song at the Library of Congress, and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle was a New York University professor; both were white. Lomax had read Hurston’s writing in a 1931 article, “Hoodoo in America,” in the Journal of American Folklore. “Dazzled” by her work, Lomax understood that he and Barnicle would never have the kind of access to southern Black life Hurston could provide.

Indeed, Hurston set their entire research itinerary. The trio first drove to St. Simon’s Island in Georgia where, Lomax wrote in a letter back to his boss in D.C., “we were soon living in an isolated community…on such friendly terms with the Negroes as I had never experienced before.” St. Simon’s residents, he said, “have been perfectly natural and easy from the first on account of Zora who talks their language.” By the time he, Hurston and Barnicle departed St. Simon’s for their next destination, they had already pressed dozens of records of authentic folk music—work songs, spirituals, “jook joint” medleys—as well as the first recorded audio interview of a formerly enslaved person.

Hurston next steered their roadtrip to her hometown. Eatonville was one of the first all-Black incorporated, self-governing towns in the United States—“charter, mayor, council, town marshal and all,” as she describes it at the outset of her memoir. The town was immortalized in Hurston’s first novel; Jonah’s Gourd Vine unfolds among the town’s orange groves and fragrant gardenia blossoms, which residents called Cape Jasmine.

In the summer of 1935, though, Hurston was in folklore-gathering mode. While touring with Lomax and Barnicle, she was also putting the finishing touches on her next book. Mules and Men, a landmark study of Black southern folkways, was published several months later. “It was only when I was off in college, away from my native surroundings,” she noted in the book’s introduction, “that I could see myself like somebody else…I had to have the spy-glass of Anthropology to look through.

In Eatonville, on the day this photo was taken, the town’s children came out to perform, essentially, for the research team. Lomax wielded the camera while Hurston directed the kids’ play and documented their games. A few years later in Dust Tracks she would wax nostalgic about her own childhood games, saying, “[o]n moonlight [sic] nights, two-thirds of the village children from seven to 18 would be playing hide and whoop, chick-mah-chick, hide and seek, and other boisterous games in our yard.” With the children assembled around her, Hurston was both observer and participant—in her innovative ethnographic practice, the roles often overlapped.

The team also engaged Eatonville’s best musicians, the most outstanding of whom was guitarist Gabriel Brown. Using the Library of Congress’s cumbersome mobile studio, Hurston and Lomax recorded Brown as he played the classic ballad “John Henry” on slide guitar.

From Eatonville, Hurston, Lomax and Barnicle went to Belle Glade, Florida, where they recorded songs from the migrant laborers around Lake Okeechobee in the Everglades. “[F]olk-songs are as thick as marsh mosquitoes,” Lomax excitedly reported to the head of the music division of the Library of Congress. He was effusive in his praise of Hurston, writing back to Washington that she was “the best informed person today on Western Negro folklore” and “has been almost entirely responsible for the great success of our trip.” In just two months, the researchers had gathered an incredibly rich assemblage of sound. For her efforts, Hurston received just $100 per month.

She had planned to accompany the team to the expedition’s next stop in the Bahamas, but after a falling out with Barnicle, stayed in Florida instead. Their relationship had soured after an argument in Eatonville, when Barnicle had tried to take a photograph of a young Black boy eating watermelon. Unlike this image, which captures Eatonville’s youngest in their full humanity, Barnicle’s impulse was all the evidence Hurston needed that, to the NYU professor, the people they had met were no more than stereotypes.

By contrast, to Hurston, Eatonville was “a city of five lakes, three croquet courts, three hundred brown skins, three hundred good swimmers, plenty guavas, two schools, and no jailhouse.” It was where she first learned how to tell stories by eavesdropping on the porch at the town’s general store. It was where her father had served three terms as mayor. And to her its people, as she would describe Eatonville’s residents in Dust Tracks, were simply “the home folks.”

At American Experience we're always coming across photos from the past that we can't stop thinking about—images that are worth a thousand words.