Narrator: In the early morning of April 21, 1865, a train draped with black bunting slowly departed Washington. In the second-to-last car rode the body of the America’s first assassinated President: Abraham Lincoln. Over the next 12 days, the funeral train would wend its way across the country. Millions paused to stand by railroad sidings, or file past his open casket to glimpse the martyred president’s face.

David Blight, historian: It’s a nation mourning, it’s a people mourning, it’s a whole society mourning, but in the end, they’re mourning the death of a simple man like themselves, who came from a place like they came from.

Harold Holzer, writer: You could not write this from scratch. You could not invent this and make it believable, the life and the death. He’s an authentic hero who is bigger than life, bigger than war, and almost bigger than America by the time he died.

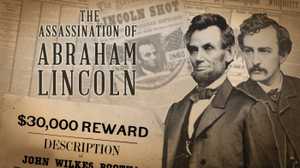

Narrator: At the very moment Lincoln’s funeral train departed Washington, his murderer lay shivering in the reeds beside the banks of the Potomac River. The largest manhunt in American history was closing in and John Wilkes Booth managed to scribble a few words in his diary.

John Wilkes Booth (Will Patton): Our cause being almost lost, something decisive and great must be done. A country groaned beneath this tyranny, and prayed for this end, and yet now behold the cold hands they extend to me. God cannot pardon me if I have done wrong. Yet I cannot see any wrong.

James L. Swanson, writer: It’s often said that Booth killed Lincoln because he was a failed actor, because he went mad. John Wilkes Booth shared political views that were identical to the views held by millions of southerners, hundreds of thousands and likely millions of northerners. John Wilkes Booth was not insane, he was not mad, unless you think the country was mad.

Gene Smith, writer: For 150 years, people have asked, why did this handsome, rich, happy young man. Why did he do it?

Terry Alford, historian: While millions of people dislike Lincoln and hundreds of thousands fought against him in armies and thousands wanted to see him dead and maybe dozens even daydreamed about it, only one person in millions stepped up to him with a pistol and that was John Wilkes Booth.

Narrator: The night of April 13, 1865 was one of the most radiant any one in Washington could remember. With the agony of the Civil War drawing to a close, the city celebrated peace by draping itself in lights.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, historian: There’s an incredible sense of jubilation that the war is coming to an end, and it was witnessed in the light: the spectacular scenery, with the crowds on the street and the lights in all the windows, it must have been a beautiful thing to behold.

Narrator: “The Great struggle is over,” editorialized the New York Times. “The history of blood is brought to a close. The last shot has been fired. The last man, we trust, has been slain…” That night, John Wilkes Booth walked among the revelers in a haze of resentment and alcohol.

James L. Swanson, writer: He heard the taunts against General Lee and the Confederate army. He saw the Union soldiers in their uniforms marching up and down the streets, celebrating. It was the most beautiful, joyful night in American history since we had won the Revolutionary War. And John Wilkes Booth had to witness it all.

Narrator: Later, a disconsolate Booth wrote his mother a note.

John Wilkes Booth (Will Patton): “Everything was bright and splendid. More so in my eyes if it had been a display in a nobler cause. But so goes the world. Might makes right.”

James L. Swanson, writer: When he went to bed that night, he was a man with little hope. He was a man without prospects. He was a man who felt his world and everything he held dear had been crushed and humiliated.

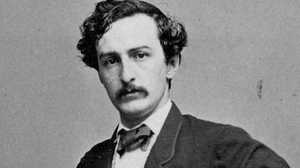

Narrator: John Booth grew up on his family farm in Bel Air, Maryland.

James L. Swanson, writer: He really grew up in a country style, horseback riding. He spent a lot of time outdoors. He had a very idyllic, free childhood

Edward Steers Jr., writer: He had a very vivid imagination. So much so that he could create all sorts of fantasies in his own mind.

Terry Alford, historian: When he was ten or twelve he got an old lance that a soldier had brought back from the war with Mexico and could be seen riding around the woods making heroic speeches and mounting mock charges against trees and bushes.

Gene Smith, writer: The words winning, buoyant, gaiety, joyous, cheerful, laughing, it turns up in the mention of Johnny by anybody who knew him.

Narrator: To the Booths of Maryland, greatness was assumed as a birthright. Led by their patriarch, the flamboyant and eccentric Junius Brutus Booth, the family was known as the foremost theatrical dynasty of their time.

Gene Smith, writer: He was the son of the greatest actor in America. His brother Edwin was on his way to inheriting the mantle and Johnny Booth saw himself, I suppose the modern word would be, “entitled.”

Narrator: By 17, John had decided to follow his famous father and brother onto the stage.

James L. Swanson, writer: Booth was terrible when he began. He didn’t know how to perform; he would mess up his lines. But he developed special skills that his father didn’t have and his brother Edwin didn’t have.

Terry Alford, historian: When you went to see John Wilkes Booth you knew you would get your money’s worth. You were going to get some very exciting stage action. He electrified you with his movements. A tremendous swordsman.

Gene Smith, writer: He had presence, he had flair, he had dramatic impulse, he had a fiery quality on the stage and off the stage. And he was gorgeous to look at.

Narrator: In 1958, at the age of 20, Booth began traveling the country as a featured performer.

Terry Alford, historian: He appears to be in fact the first American actor who had his clothes ripped by fans when he was coming out of the theater one night. He was adored.

Gene Smith, writer: This dramatic, handsome young man, filled with excitement, with vibrancy, took the stage by storm.

Narrator: Just as Booth reached stardom, however, the country itself was losing interest in idle pursuits like the theater. A much more vivid drama was turning North against South, and brother against brother. The Booths were no exception.

James L. Swanson, writer: Edwin really became a man of the North. He became a star in the North. And his political consciousness developed along those lines. John Wilkes spent most of his time in the South. That’s where he received his great acclaim, that’s where he felt best loved. And over time he naturally adopted the Southern point of view.

Narrator: “We are of the North!” Booth’s sister Asia once insisted. “Not I,” he replied. “So help me God, my soul, life and possessions are for the South.”

Terry Alford, historian: There was a really big burden to being a Booth whether you went on the stage or not. You have these giants in your family that you’re inevitably compared to and to some extent, as a young man, he needed to just psychologically to individualize himself from them and to show that he was his own person.

Narrator: While his family dispersed across the North, Booth spent most of his time in Richmond, Virginia, the citadel of the South.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: He viewed the South as the ideal type of society. Unlike the North, which he considered rough, mongrel, the South was pure. He did not view slavery as an evil. Slavery was God’s blessing to the African-American, it brought him to Christianity, it brought him to higher civilization. It was the abolitionists in the North that were splitting this country apart and he hated abolitionists, he hated the anti-slavery movement.

Narrator: When radical abolitionist John Brown was captured while trying to incite a slave rebellion in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, Booth heeded a call for volunteers to guard against Brown’s escape. He couldn’t help but be impressed as Brown held the nation spellbound from his prison cell, issuing bloody prophecies about the fate of the Union.

Terry Alford, historian: One of the interesting features of John Wilkes Booth is his fascination with romantic characters, with heroic characters in particular. People who defined the age, people whose acts made everyone stand up and pay attention to what he was doing. He loved characters in the heroic mold.

Narrator: In November, 1860, a little-known Illinois politician named Abraham Lincoln was elected President. The victory of an anti-slavery Republican provoked seven states to secede from the Union, and enraged millions of Southern sympathizers, including John Wilkes Booth. “We used to laugh at his patriotic froth whenever secession was discussed,” Edwin Booth remembered. “That he was insane on that one point, no one who knew him can well doubt.”

Terry Alford, historian: Shortly after Lincoln’s election, Booth wrote a speech. He apparently wrote this to deliver to an audience. It doesn’t appear that he ever had an opportunity. But it is a great window into Booth’s mind. And it shows us that Booth is terrifically disturbed by the division of the country. That he blames the abolitionists entirely and essentially he sees what’s happening as a giant John Brown raid on the South.

John Wilkes Booth (Will Patton): You all feel the fire now raging in the nation’s heart. It is a fire lighted and fanned by Northern fanaticism, a fire which naught but blood can extinguish. The South wants justice, has waited for it long, she will wait no longer.

Narrator: “This war is eating my life out,” President Abraham Lincoln once said. “I have a strong impression that I shall not live to see its end.” The small skirmish that Lincoln thought would be quickly over had, by 1862, turned into a bloody stalemate with no end in sight. Lincoln haunted the War Department, where reports of casualties preyed on his mind.

Joshua Wolf Shenk, writer: This is not an abstract conflict. The important battlefields could be heard, or could be gone to very quickly. The casualties stumbled into the capitol. Lincoln was someone who felt death and disappointment and difficulty extremely clearly. It was always with him: the sheer physical grueling horror of it.

Harold Holzer, writer: Lincoln assumes the-the role of a sort of a bereaved and grieving father. He does absorb all of the loss and it ages him and it weighs him down and it makes him so melancholy and somber.

Narrator: In February, 1862, death reached out and touched Lincoln’s own family. His beloved 12 year-old son Willie fell sick with typhoid, contracted from drinking tainted water. After a weeklong illness, Willie died.

Harold Holzer, writer: The light went out of his life and he mourned very, very deeply, and then he was forced to go back into the work of seeing other boys die.

Joshua Wolf Shenk, writer: He was constantly wondering, why is this happening? What was God’s purpose in this death? Why would he be so afflicting? Not only to the nation but Lincoln personally. It calls to mind the Biblical story that Lincoln was seen reading in the White House, which was the Book of Job. This man who just has everything taken from him. Job collapses, as Lincoln collapses. But that’s not the end of the story. The collapse is on its way towards some new understanding of the nature of reality and the moral universe.

Narrator: Out of suffering, Lincoln resolved must come “a new birth of freedom.” If so many had to lose their lives, it must be so that many more could gain their freedom. In January, 1863 Lincoln issued an order freeing the slaves in the rebellious Confederate states. His Emancipation Proclamation transformed the meaning of the war.

David Blight, historian: He’s now linked the cause of black freedom to the cause of the preservation of an American republic, which means in effect, the war is being fought to reinvent the United States, not to preserve it. The government, the republic, that would come out of this war, would not at all be the same anymore.

Allen C. Guelzo, historian: What else could all this death and suffering and blood mean except a greater understanding of what it is to be a free people?

Joshua Wolf Shenk, writer: He believed that the government was built on an idea and that this was a war over an idea. And to surrender, to withdraw, to compromise on that idea would be to surrender something precious for all humanity, for all time.

Narrator: “I expect, to maintain this contest until successful,” Lincoln wrote, “or till I die or am conquered, or the country forsakes me.”

James M. McPherson, historian: There was no more talk of conciliation, no talk of compromise through some kind of political process. This is an outcome that can only be “tried by war and decided by victory. Tried by war, decided by victory.” Those six words put it, said it all.

Narrator: The trial of war would last far longer than Abraham Lincoln ever imagined. With Southern victories at Manassas, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, public opinion in the North began to falter. In the summer of 1863, draft riots broke out in several Northern cities. Newspapers denounced Lincoln with what one friend called a “frantic malignancy.” Soon sentiment was so strongly against him that Lincoln was certain he would lose his bid for reelection. “The people are impatient,” he said. “The bottom is out of the tub.”

Allen C. Guelzo, historian: The costs are mounting, the politicians are complaining, and the voters are turning against him. And by the end of August 1864, Lincoln has concluded, “If we come to the polls like this in November, we’re going to lose.”

Narrator: Salvation for Lincoln came in the form of a battlefield victory. On August 31st, General William Tecumseh Sherman broke through the Confederate defenses around Atlanta. He sent a short telegram to President Lincoln: “Atlanta is ours and fairly won.”

James M. McPherson, historian: When that was published in the Northern newspapers, it changed Northern opinion around almost overnight. Lincoln, who looked like the defeated and discredited commander-in-chief of a losing army now emerges as the leader of a triumphant army and he was triumphantly reelected.

James L. Swanson, writer: Something turned in Booth when Abraham Lincoln was reelected. He realized Lincoln was in there for good, to prosecute the war to the end. He knew Lincoln was not going to settle with the South and that many more would die, that Lincoln was going to serve another four years in the White House.

David Blight, historian: These Yankees, led by this “black Republican” — as they called him — Abraham Lincoln, were going to use this war now to tear up the South, to destroy its institutions, to overthrow its way of life, and to end their civilization as they had known it.

Narrator: By 1864, John Wilkes Booth was only 25 years old, yet he had already begun losing interest in his acting career. “I hardly know what to make of you,” his agent wrote him. “Have you lost all your ambition?”

Terry Alford, historian: I don’t think we should forget that acting in those days, is very, very hard work. There’s travel, there’s exhausting performances, they are drafty theaters, managers who won’t pay you and I think at some point Booth began to tire of the stage.

Narrator: To Booth, the war had rendered his life marginal and irrelevant. “What are actors?” he wrote. “They know little, think less, and understand next to nothing.” Booth’s dreams of glory beyond the stage were quickly passing him by. He had nothing to show for the war, but the scars of a few overzealous stage duels.

John Wilkes Booth (Will Patton): For four years I have cursed my willful idleness and begun to deem myself a coward. I cannot longer resist the inclination, to go and share the sufferings of my brave countrymen, against the most ruthless enemy the world has ever known.

Narrator: Booth’s anger and disappointment began to focus on the one man he held responsible for the South’s suffering.

Terry Alford, historian: There’s no doubt that the war was pushing Lincoln forward as a symbol, an icon, something bigger than life. Booth began to focus on Lincoln in this way, that Lincoln in fact was the source of all the nation’s troubles.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: Because of the war, Lincoln had to institute a whole series of acts that were viewed as very anti-democratic. Suspension of the writ of habeas corpus for instance, shutting down newspapers, censoring people’s speeches. All of these things were an anathema to John Wilkes Booth and he viewed himself in the end I think as someone that literally god had put here to correct the tyranny of Abraham Lincoln.

Terry Alford, historian: Early on, Booth seems to have developed this passionate hatred for tyranny. It’s curious where that came from. If we remember that his father’s middle name was Brutus, that may tell us a good bit. Brutus of course was the character who assassinated Caesar and if you look both in the play of Shakespeare and in the writings of the historians of ancient Rome, Brutus was a character as noble as Caesar, as distinguished as Caesar, as well-regarded as Caesar and whose patriotism and decency were unquestioned.

Narrator: Like Brutus, Booth dreamed of a single, grand gesture that would turn the tide of history and catapult himself into immortality.

James L. Swanson, writer: John Wilkes Booth felt he had to justify why he wasn’t a soldier on the front lines. Why didn’t he volunteer? Why wasn’t he fighting? Booth thought his resources, his talent and skill could be put to better use.

Narrator: Booth began taking on small assignments for the Confederate Underground, a loose network of Southern spies living north of the Mason Dixon Line. It was here, in the ferment of the Underground, that Booth settled on a bold plan. He would kidnap the President of the United States, convey him south to the Confederate capitol in Richmond, and ransom him for thousands of Confederate prisoners.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: The idea of capturing or kidnapping a United States president may seem preposterous on the surface, but at the time it was quite feasible. Lincoln was unprotected. He moved about frequently on his own. And he traveled as much as three miles to his summer residence at Soldiers Home, often unattended, by himself.

Narrator: In November and December, Booth made several trips to Southern Maryland, a hotbed of sedition, where he began to recruit co-conspirators and scout escape routes.

James L. Swanson, writer: His most valuable conspirator was John Surratt. College educated, Confederate courier, known in Richmond. He helped Booth interact with other Confederate agents. Without John Surratt, Booth couldn’t have organized the conspiracy.

Narrator: Surratt introduced Booth to twenty nine yr-old George Atzerodt, a German-born carriage painter and boatman. During the war, Atzerodt secretly ferried Confederate agents across the waterways of Southern Maryland. Surratt also introduced Booth to David Herold, 22, an impressionable and dull-witted pharmacy clerk, who knew the back roads that would serve as the conspirators’ escape route. Lewis Powell, tall and powerful, was a former Confederate prisoner of war who would provide the muscle for the kidnapping conspiracy. Rounding out the group were two of Booth’s childhood friends, Samuel Arnold and Mike O’Laughlen — both ex-soldiers in the Confederate Army. The group had little in common other than a strong attraction to the charismatic actor who would be their leader.

James L. Swanson, writer: It was as though a great star of the modern age picked you, a completely anonymous, unknown person of no status, no wealth, no importance, a great star picks you to be his confidante, his pal, his companion, to travel with, to dine with, drink with. Many of them didn’t join the conspiracy because they hated Abraham Lincoln, they joined the conspiracy because they loved and admired John Wilkes Booth.

Narrator: On March 4th, 1865, more than 50,000 people gathered under rainy skies to witness Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inauguration. After four harrowing years, the end of the war was at last in sight. Lincoln stood to address the crowd, just as a brilliant ray of light pierced the clouds overhead. “Let us strive on to finish the work we are in,” Lincoln implored, “to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan; to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace”.

David Blight, historian: There’s not even a moment of bitterness. There’s not even the slightest declaration of what will be done with Confederate leadership. It is remarkable that in a moment like that, in this country that has all but won a victory in an all-out, terrible, total civil war, and he doesn’t even spend one sentence to declare the righteousness of victory and the evil of Confederate defeat.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, historian: What he does is to suggest that the sin of slavery was shared by both sides. His way of reaching out to the south: “Both sides read the same bible, both prayed to the same God, neithers prayers were fully answered.” And then of course the words we remember: “with malice toward none, with charity for all, let us bind up the nation’s wounds.”

Narrator: Standing on the steps of the Capitol that day, only yards from the President, John Wilkes Booth seethed with hatred. For Booth, the prospect of another Lincoln term held not consolation, but the sting of bitterness and defeat. “What a splendid chance I had,” he’d later confided, “to kill the President where he stood.” Two weeks later, Booth and his co-conspirators met in the private dining room of a Washington restaurant. Over oysters and champagne, Booth laid out his kidnapping plan.

James L. Swanson, writer: When Booth started to reveal the details, they thought he was a madman. We’re going to kidnap Abraham Lincoln; we’re going to get him at Ford’s Theatre. He said, one of you will turn down the gaslights at the signal and the theater will be plunged into darkness. Lewis Powell will get into the president’s box. He’ll be the one who’s going to subdue Lincoln, tie him up and then lower him to the stage with a long rope while the theater is plunged into darkness.

Narrator: Samuel Arnold scoffed at the audacity of Booth’s plan. “You can be the leader of the party,” he said, “but not our executioner.”

Gene Smith, writer: He says, “Johnny, all this is going to be done in front of an audience that will include several hundred soldiers of the Union Army?” And having gotten him out the back, if the soldiers don’t intercede, nobody is going to give the alarm throughout Washington, which is crawling with Yankee soldiers, cavalry patrols, and police?” He said, “it is madness beyond measure.”

Narrator: On April 3, the Confederate Capitol of Richmond, finally fell to Union forces. The President himself toured the smoldering ruins, as newly freed slaves rushed to embrace him. Six days later, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at the small town of Appomattox Courthouse. After four bloody years, the war was over. The Confederacy in ruins and his kidnapping plot in tatters, Booth sank into disappointment and bitterness.

James L. Swanson, writer: By April, 1865, Booth was certainly disillusioned. Think of what he had to endure from his point of view: a few months before, the reelection of the great tyrant. His failure to kidnap the president shamed him. What was his future in the defeated, crushed South?

Narrator: Out of his disappointment, Booth began to hatch a new, even more desperate plan.

Terry Alford, historian: He will punish the North, through Lincoln; he will punish the North for what it’s done to the South. Now revenge is not a very noble motive, but we all understand it is a very compelling human motive and sometimes it overwhelms.

Narrator: The morning of April 14th, 1865, Abraham Lincoln awoke unusually cheerful. Less than a week after the surrender of the Confederate Army, he allowed himself a moment of satisfaction.

Joshua Wolf Shenk, writer: He seemed relieved. His face looked different. He had color; he had life in a way that he hadn’t all through the war.

Narrator: “He was transfigured,” wrote one close friend. “That indescribable sadness had been suddenly changed for an equally indescribable joy.”

Harold Holzer, writer: It is indeed the first day that he really feels that Washington is free and at peace.

Narrator: At the morning cabinet meeting, Lincoln again expressed his desire for clemency towards the South. Then, in his usual way, he regaled his cabinet with stories.

Allen C. Guelzo, historian: Lincoln even talks about a dream that he had, a dream that he was standing on the deck of a ship, the ship was heading towards a dim shore ahead. He said it was a dream he’d always had at important turning points in the war and he was convinced that he’d had the dream again because this was now the last great, final turning point.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, historian: He invited Mary to a carriage ride that afternoon, just the two of them together. They talked about what it might be like in Springfield, when they went home again to the place where they had begun, and he said to her, 'Mary, we’ve got to try to be happy now, our future is ahead of us’. And then that night they go to the theater.

Narrator: That same morning, John Wilkes Booth awoke late. He made his way to Fords Theater to pick up his mail, held for him by the theater’s owners.

James L. Swanson, writer: And then somebody at Fords Theatre said, 'President Lincoln is coming tonight’. That was the moment. He’s sitting on the front step of Ford’s Theatre and someone tells him, he’s coming here tonight.

Narrator: “He left the theater in a kind of hurry,” remembered one onlooker, “as if he had made up his mind about something to be done.”

Terry Alford, historian: Once Booth learned that Lincoln would be at the theater that night, he had essentially eight hours or so to get ready, and he went into a frenzy of action.

James L. Swanson, writer: He checked on his horse. He made sure his derringer pistol was ready. He thought about what he had to take on the road during his escape.

Narrator: That afternoon, Booth returned to Ford’s theater. He went to the President’s box and, in a small antechamber, he carved a small mortise in which to brace a stick of wood. The other end would bar the door from the inside. An hour later, Booth convened what remained of his accomplices at a restaurant nearby. He informed them of a startling change of plans.

James L. Swanson, writer: Tonight, in about two hours I am going to kill Abraham Lincoln. You Lewis Powell will murder the secretary of state, William Seward. George Atzerodt, your job is to murder the vice president, Andrew Johnson. Booth of course reserved the greatest act for himself. He would perform the Lincoln assassination solo.

Narrator: That night, the Lincolns set out for Fords Theater around eight pm. Having been turned down by a series of more luminous guests, the Lincolns stopped to pick up a young friend of Mary’s named Clara Harris and her fiancé.

James L. Swanson, writer: Booth reached into his pocket, handed him a small piece of paper, probably a calling card. And of course Booth’s calling card would admit him to almost any place in Washington.

Terry Alford, historian: Booth then opens the outer door leading to the vestibule to the box, and closes it. And then picks up the wood stand that he had left behind the door earlier in the day and uses it as a brace, wedging it between the door and the hole that he cut out in the wall.

James L. Swanson, writer: Now he’s one door away from Abraham Lincoln. He can hear the sound of the play, the actors speaking. It’s dark in there. He walks up to the door and he looks through a peephole.

Narrator: Below, the play had reached a climax, as actor Harry Hawk prepared to deliver his biggest laugh-line of the evening.

James L. Swanson, writer: He was waiting to hear that line. The other actors leave the stage, Harry Hawk stands there alone and he says the line.

Narrator: Suddenly a shot rang out through the auditorium. Corporal Rathbone leapt to his feet and Booth swung his dagger cutting the young officer’s shoulder to his elbow.

James L. Swanson, writer: Booth turned from Rathbone and began swinging his leg over the balustrade and he caught one of his spurs on the bunting and on the framed photograph of George Washington that hung at the front of the box.

Narrator: Landing awkwardly on the stage below, Booth broke his left ankle. Audience members later would disagree about what he shouted next. Many heard: “Sic Semper Tyrannis,” 'Thus Always To Tyrants.’ Others: “the South is avenged.”

Terry Alford, historian: He remained almost frozen for a minute as he struggled to gain his composure, and what he later told a friend was all the courage he could muster, he got to his feet and started for the wings.

Allen C. Guelzo, historian: People look at each other for a moment: is this part of the play? What is all this about?” This lasts for a second, two seconds, three seconds; that’s when the shouts go up: “The president has been shot!” “Somebody stop that man!” People scramble up on the stage apron but Booth has already bolted past the scenery, past the curtains, out the back entrance. He’s on a horse; he gallops away into the dark of Washington.

Narrator: As Booth made his escape, his co-conspirators were not faring as well. Around 10:15, Lewis Powell knocked on the door of Secretary of State William Seward’s mansion. After forcing his way up the stairs, he entered Seward’s bedroom, where the Secretary was recovering from a broken jaw suffered during a carriage accident.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, historian: He has a huge Bowie knife, comes to Seward’s bedside, slashes his face with such force that his cheek is torn off. He loses so much blood that it is astonishing that he didn’t die right then. He is scarred for life; however, because of the way the jaw was wired, because of the carriage accident, he missed the jugular vein.

Narrator: As the alarm was raised, one of Seward’s sons along with a nurse rushed the would-be assassin. Powell dropped his knife and escaped down the stairs and out the door. At the same time, George Atzerodt, approached his quarry: Vice President of the United States Andrew Johnson. But as he neared Johnson’s residence, he lost his nerve.

James L. Swanson, writer: Atzerodt never went up those stairs, he never knocked on the door, he never tried to assassinate the vice president of the United States. He was the only conspirator of Booth who failed his master that night.

Narrator: Inside Fords Theater, a young Navy surgeon was the first to gain access to the Presidential box.

James L. Swanson, writer: He cuts open Lincoln’s shirt. He can’t find the wound. There was no blood on him at all. He just won’t wake up. So now the question is where shall the president of the United States die? It can’t be on the floor of a theater box.

Allen C. Guelzo, historian: Ten feet across F Street from Ford’s Theatre is a young man standing out in front of a boarding house who shouts over the din in the streets they should bring him over here, and they carry Lincoln’s body across the street, up the small winding steps of the Petersen Boarding House into the back bedroom, and they lay him out crosswise across the bedstead that is in the back bedroom. And that is when the deathwatch begins.

Narrator: By now, the attending doctor had found a small bullet hole below Lincoln’s left ear. He declared the wound mortal. One by one, as they received the terrible news, Lincoln’s cabinet members rushed to the Peterson House. “The giant sufferer lay extended diagonally across the bed,” remembered Navy Secretary Gideon Welles. “His slow, full respiration lifted the bedclothes with each breath. His features were calm and striking.”

Edward Steers Jr., writer: After he was completely stripped and covered in blankets and hot water bottles, Mary Lincoln was brought into the room to see him. And she basically became hysterical. She kept pleading with Lincoln, pleading with him to open his eyes just to say one word to her, but of course he couldn’t.

Narrator: Amid the chaos, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton took charge.

Allen C. Guelzo, historian: It’s Stanton who was actually the man who keeps his head. He needs to get evidence, he needs to get witnesses, he needs to get depositions.

He wants troops put on alert, he wants certain arrests made, he wants bridges closed, he wants a cordon put around Washington. In a situation like this, there was no precedent.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: The idea that this was done by individuals just was incomprehensible. It had to be — it had to be something much larger, much wider that wasn’t finished yet.

Narrator: By 11:30 pm, more than an hour after he had fled Fords Theater, John Wilkes Booth rendezvoused with Davey Herold in the Maryland countryside. After picking up rifles and a bottle of whiskey at a Country Inn owned by Mary Surratt, they headed south toward Virginia and possible escape into the deep South.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: Booth was now suffering from the break in his leg. He was clearly conscious of it now. The adrenaline had stopped flowing, the pain had taken over.

Narrator: Knowing they needed medical attention, the fugitives galloped southeast toward the home of a country doctor named Samuel Mudd, whom Booth had met months before while scouting escape routes through Maryland.

Terry Alford, historian: From the Surratt house to Dr. Mudd’s was about 17 miles through a difficult country, a road not always well marked, pretty narrow in spots, washed by rain at spots through a swamp and pine forest.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: It was now overcast and a light drizzle was falling and they had to make their way without the aid of moonlight. It took them approximately four hours to get to Mudd’s house. They arrived just before four o’clock in the morning. Herold dismounted, went to the door, pounded on it. Dr. Mudd examined Booth, removed the boot from the leg and determined it was broken. He set the broken leg, and told Booth that he needed to rest. And so he took him upstairs and put him to bed in an upstairs bedroom.

Narrator: As Booth slept, word of what he and his accomplices had done raced through the Capitol.

James L. Swanson, writer: People would encounter each other in the street and say, 'The president has been shot, no, the Secretary of State has been attacked and he was stabbed. No, it’s Lincoln, no it’s Seward.’ Then they realized it’s both.

Gene Smith, writer: Rumors spread that they had slaughtered the Supreme Court justices, they had burned the Congressmen, people were afraid to go to bed at night, every horse that passed by they took to be the Confederate cavalry, people were running through the streets; it was a horrible situation.

Narrator: Inside the Peterson House, as dawn approached, Abraham Lincoln was quickly fading.

Harold Holzer, writer: In the room, it’s eerily quiet. Lincoln’s breathing is horrible to hear because he’s taking deep breaths and he’s rattling and wheezing, and sometimes he doesn’t breathe for what seems like forever.

Narrator: Finally, at 7:22 in the morning, the Surgeon General pronounced the vigil over. Abraham Lincoln was dead. “We all stood transfixed in our positions,” remembered one witness, “speechless around the dead body of that great and good man.”

Doris Kearns Goodwin, historian: These men who by that time had come to love Lincoln showed their feelings crying at that bedside. And then of course, Stanton uttered the words that had come down through time. “Now,” Stanton said, “he belongs to the ages.”

Harold Holzer, writer: They send for a coffin and that’s when many people first realize that he’s dead, when they see this wooden coffin being taken up the stairs. And then a bit later, the doors swing open and the soldiers bring the coffin out again, and you can tell from their struggles that it’s — this time it’s occupied.

Narrator: By the morning of Lincoln’s death, telegraphs reporting the assassination had reached nearly every major city in America. That evening, headlines broke the shocking news. “The sun set last night on a jubilant and rejoicing nation,” wrote the New York Herald. “It rose this morning upon a sorrow-stricken people.” No one grieved more than the nation’s newly freed slaves. “There will be sadness today, such as needs no funeral orations or badges of mourning,” wrote the New York Times. “The tears of the forgotten, outcast and oppressed slave will be the sincerest tears that fall on the grave of the President.”

Allen C. Guelzo, historian: Many black people feared that with Lincoln’s death they would be, in fact, returned to slavery, that the Emancipation Proclamation would somehow be revoked.

Narrator: Four hours after Lincoln’s death, Andrew Johnson was sworn in as the new President, restoring a measure of stability to the national government.

Gene Smith, writer: The fear quickly vanished and it was replaced by a fervent rage.

Narrator: In the field, Union Soldiers were kept unaware of Lincoln’s death for several days for fear that they might seek retribution.

Allen C. Guelzo, historian: Anyone known to profess Confederate sympathies would be well advised to stay indoors with the shutters closed and the doors locked. People on Washington streets who might, with too great a load on from celebrating, say something like, “Oh, I’m glad they shot old Abe,” would come within an inch of being lynched.

Narrator: Within hours of Lincoln’s death, mobs had formed in many Northern and occupied Southern cities. In San Francisco, throngs destroyed the newspaper offices of the Democratic Press. In Washington, vigilantes surrounded a jail holding Confederate prisoners. Two former-Presidents — Franklin Pierce and Millard Fillmore — faced angry crowds outside their homes after they failed to show evidence of mourning.

James L. Swanson, writer: It was a dangerous time. Up to 200 people were murdered in the streets of America’s cities within two or three days of the Lincoln assassination.

Narrator: None suffered more in the hysteria than the Booth family itself. Fearing for his life, Edwin Booth stationed guards outside of his New York home. “Think no more of him as your brother,” Edwin wrote his sister Asia, “He is dead to us now, as he soon must be to all the world.” Within days, federal agents raided Asia Booth’s home where they discovered a trove of papers, including a personal manifesto, which her brother John had asked her to keep safe.

John Wilkes Booth (Will Patton): Right or wrong, God judge me, not man. For four years have I waited, hoped, and prayed for the dark clouds to break, and for a restoration of our former sunshine. To wait longer would be a crime. God’s will be done, I go to see and share the bitter end.

Narrator: In the late afternoon of April 15th, Dr. Samuel Mudd, finally realizing the danger he was in, ordered Booth and Herold from his home.

Terry Alford, historian: Booth was heavily armed, in his house, with his wife and four children. Mudd simply could not afford to host a shootout in the family parlor. So his idea was to get Booth out of there, get gone and pray for good luck.

Narrator: The fugitives rode off in the direction of the Zekiah swamp, a nearly impassable snarl of creeks and bogs bordering the Potomac. They wandered in the swamp for several hours, until they found the home of a known Confederate sympathizer who directed them to a thicket of pine trees on his property.

Terry Alford, historian: This is a real thick stand of young pine trees so thick in fact that the visibility in there was only thirty, forty feet at the maximum.

Narrator: In the morning, the fugitives were awakened by a series of short whistles. An Agent of the Confederate Underground named Thomas Jones had been alerted to their presence in the Pine Thicket.

James L. Swanson, writer: Thomas Jones told Booth, 'You have to stay in this pine thicket. The troops are everywhere. You can’t outrun them. The trick is going to be, you stay in place while the soldiers pass through the area and move on, then when the moment is safe I’ll take you down to the river and we’ll cross.’

Terry Alford, historian: Besides the occasional visit from Jones, usually in the late morning, Booth and Herold were left alone in the pine thicket. It was obviously quite lonely in there, and close enough to the road from time to time to hear the pursuers riding up and down it. On one occasion they even heard voices of these Union cavalrymen shouting at each other.

Narrator: It was cold and wet, but the fugitives could not light a fire for fear of discovery. To quiet their horses, Herald led them deep into the swamp and shot them, allowing their bodies to disappear into the thick ooze.

Terry Alford, historian: Booth asks Jones of course for food, and news, and particularly newspapers. He wanted to know what the public thought about the assassination. What were the reviews of this final performance of his. And when he got the papers from Jones, he was absolutely stunned. The country was furious with him. From right to left across the spectrum, from Copperheads to radicals to Southerners to Northerners, they denounced Booth in blistering language.

Narrator: His head once filled with visions of triumph, Booth now staggered from the sheer scale of the betrayal.

John F. Andrews, Shakespearean Scholar: I don’t think there’s any doubt that John Wilkes Booth expected to be remembered as a noble patriot, as someone who had in effect become the American Brutus.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: He had liberated the country from under this terrible despot’s heel and the thanks that he got was to be treated as some sort of base villain.

Terry Alford, historian: Booth had on him a little pocket notebook that he had purchased the preceding year, and in it he began to write down his reaction to the reaction of the public to the murder of Lincoln.

James L. Swanson, writer: He wanted to write about what he did. He wanted to justify what he did. And he wanted to be remembered. These were his notes to the play; These were the director’s notes. He had to leave that behind. He didn’t want to vanish from history without leaving us his own voice.

John Wilkes Booth (Will Patton): I struck boldly and not as the papers say. I walked with a firm step through a thousand of his friends, was stopped but pushed on. I passed all his pickets, rode 60 miles that night with the bones of my leg tearing my flesh with every jump. I can never repent it. Our country owed all her troubles to him and God simply made me the instrument of His punishment.

Narrator: The day after Lincoln’s death, April 16, was Easter Sunday. In a nation steeped in religion, on the holiest day of the year, churches and Cathedrals across the land were swelled to the rafters and draped in black. In parishes from Maine to California, ministers tore up their Easter sermons and replaced them with lamentations.

Allen C. Guelzo, historian: Preachers in church after church, in pulpit after pulpit, seized upon the extraordinary conjunction of this event and all these events of religious history. And they began drawing the inevitable connection that as Christ had died to save men’s souls; Lincoln had died to save the Union.

James M. McPherson, historian: The parallels with Christ on the cross could not escape anybody. Lincoln was assassinated on Good Friday. He had taken on the burdens of the whole nation on his own shoulders, and for that he was crucified. Here is a man like Jesus, who, was killed to save the rest of us.

James L. Swanson, writer: It was with the assassination that the myth of Abraham Lincoln was born. Lincoln was not universally liked or beloved during his presidency. Millions of people hated him. Once he was assassinated everything changed.

Narrator: Amid the songs of praise for Lincoln, there were cries for revenge. “Let the (South) perish,” thundered one Northern minister. “In the grave of our murdered President, let the last vestige of them be buried.”

Gene Smith, writer: It wasn’t enough that they had revolted for four and a half long years. That they had slain on the field of battle the cream of a generation, that they had destroyed themselves. Now, to top it off, they had killed Abraham Lincoln, shot in the back in the presence of his wife. The South had indicted, tried, and convicted itself of irredeemable evil.

Narrator: In the occupied sections of the Confederacy, many feared retribution and publicly expressed their deepest condolences. But in private, many praised Booth as “our Brutus.”

“After all the heaviness and gloom,” wrote one Southern woman, “this blow to our enemies comes like a gleam of light. We have suffered 'til we feel savage. Our hated enemy has met the just reward of his life.” More than 60 hours after Lincoln’s assassination, the nation was still in a state of agitated suspense. The pressure to capture John Wilkes Booth was building.

James L. Swanson, writer: The public demanded that Booth and his conspirators be seized. And it was frustrating that day after day passed. Booth escapes Washington. Then he vanishes into Maryland. Then no one knows where he went.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: Reports were coming in from everywhere: Booth was dressed as a woman, living in the basement of some house in Washington. He was seen in Philadelphia in another disguise. Several people were arrested in the North simply because they bore a resemblance to John Wilkes Booth.

Terry Alford, historian: There was a fear. The South was so disordered and chaotic with Confederate armies disbanding, groups of guys going here and there on horseback, Booth could easily get lost in that mix.

Narrator: On April 17th, the government’s luck changed. Acting on a tip, soldiers raided Mary Surratt’s boarding house in Washington, where Booth and his accomplices had often met. As they began to question Mrs. Surratt, a knock was heard at the front door. It was Lewis Powell, the would-be assassin of Secretary of State William Seward.

Terry Alford, historian: Powell was a stranger to Washington, D.C. and he wasn’t the first stranger to get lost in this maze of streets. With nowhere to go, no food, no money, knowing no one he went to one of the only houses he knew in Washington, the home of the Surratts. Unfortunately for him, just at the moment that he chose to come, late one night, detectives were there interrogating Mrs. Surratt. When he walked in, he looked implausible to them and he got arrested.

Narrator: Tipped off by a letter discovered in Booth’s hotel room, authorities also took into custody Michael O’Laughlen and Samuel Arnold.

Narrator: The same day, they arrested Edmond Spangler, a stagehand at Fords, whom they suspected of having aided Booth’s escape. On April 20th, George Atzerodt was arrested on his cousin’s farm after he was overheard boasting about his participation in the conspiracy. Most of the prisoners were taken aboard the ironclad Montauk, where they were ordered to wear padded hoods and confined to three-foot by eight-foot cells.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: While the government had most of the conspirators in tow now and in custody, Booth and Herold of course were still out there and the government really did not have any good idea where they were.

Narrator: On April 20, Secretary Stanton announced the largest reward ever offered by the federal government — $100,000 for the capture of John Wilkes Booth and David Herold. “Let the stain of innocent blood be removed from the land by the arrest and punishment of the murderers,” Stanton wrote. “Every man should consider his own conscience charged with this solemn duty and rest neither night nor day until it be accomplished.” It was the beginning of the largest manhunt in American history. For five days and nights, as thousands of soldiers scoured the area, Booth and Herold had hidden safely in the Pine Thicket.

Terry Alford, historian: If he could just get out of Maryland, get over to Virginia, he could receive proper medical care, he would find sympathetic individuals, people who could appreciate what he had done. Finally, Jones determined that the area was clear enough of Union pursuers to attempt a crossing. They began about a three to four mile very cautious walk down cart lanes and public roads in the direction of Jones’ farm and the river. Luck was on their side for once at least. Nobody came out, nobody noticed them, no one passed along the road.

James L. Swanson, writer: It’s dark, it’s quiet, and they make it safely down the road and across the open country. Then he takes them down to the crossing point. It’s a bluff that leads down to the river.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: Jones put the two of them in a boat, he gave them a compass and a candle and pointed on the compass the number of degrees where they should head for, pushed the boat out into the water and God blessed them.

James L. Swanson, writer: All Booth had to do was cross the Potomac that night and he might make it to Virginia, might make it to the Deep South and then it would be almost impossible to catch him. So there Booth and Herold are in the middle of the night. The river is dark; it’s as black as ink, and they row the wrong way. Instead of rowing west across the river, they start heading north and west and they end up in Maryland. They haven’t even left Maryland after a night of rowing.

Narrator: As dawn broke, Booth and Herold took refuge in the weeds beside the River. Exhausted, Booth again took out his notebook to write.

John Wilkes Booth (Will Patton): I have been hunted like a dog through swamps and woods, wet cold and starving. With every man’s hand against me, I am here in despair. And why? For doing what Brutus was honored for. And yet I, for striking down a greater tyrant than he ever knew, am looked upon as a common cutthroat. I think I have done well, though I am abandoned with the curse of Cain upon me when if the world knew my heart that one blow would have made me great.

Narrator: On April 21, a special train departed Washington, DC. It carried the remains of Abraham Lincoln and his son Willie, disinterred so he could be reburied next to his father. For the next 12 days, the train would reverse the route Lincoln had taken four years earlier on his way to his first inauguration. In Philadelphia, Lincoln’s casket was displayed in Independence Hall, while a line of mourners stretching more than three miles waited to pay their respects. In New York, the next day, Lincoln’s hearse was led down 5th Avenue by 16 magnificent steeds, as bells from Trinity Church rang out. More than half a million people, a quarter of the city’s population, lined the route. From New York, Lincoln’s train made its way slowly west.

Allen C. Guelzo, historian: In remote areas people would come miles to line the track simply to stand and watch, a newspaper reporter who was with the funeral train looked out the windows, he could just see crowds upon crowds of people doing nothing but standing silently.

Harold Holzer, writer: They’re there simply to lift their caps or bow their heads as this car goes by and what they see for just the fleeting second is worth the effort and the wait, and that is a soldier standing on guard in front of a big coffin and a little coffin.

James L. Swanson, writer: The outpouring of grief and emotion during that 1,700 mile journey on the funeral train from Washington to Springfield was not just for Lincoln. The American people mourned their president, but they mourned every son, every brother, every husband, every father lost in that war.

David Blight, historian: When people wept for Lincoln, or when they went to their diaries, as many did, and they drew black around the pages, they were really weeping for themselves. They were weeping for their own kids. They were weeping for their own losses. We mourn for ourselves even when we mourn a great public leader.

Narrator: “The nation rises up at his coming,” wrote one poet. “Cities and States are his pallbearers and cannon beat the hours with solemn procession. Give him place ye prairies! Ye winds that move over the mighty spaces of the West, chant his requiem! Ye people, behold a martyr”. As Lincoln’s funeral train made its slow way across the country, the Navy boat John S. Ide was steaming down the Potomac River. On board were 25 soldiers from the 16th New York Cavalry and two detectives: Luther Baker and Everton Conger. The search party had formed as a result of a fortunate case of mistaken identity.

Terry Alford, historian: Union detectives and Union ships were watching the Potomac River very closely and some individuals were seen to have crossed it. They weren’t Booth and Herold but they were mistaken for Booth and Herold.

Narrator: In fact, the real fugitives were only a few miles ahead at a second river crossing along the Rappahannock. Having reached the small village of Port Conway they met three Confederate soldiers who agreed to escort them deeper into Virginia.

James L. Swanson, writer: These Confederates say we know a place to take you. When we get over the river we’re going to take you to the Garrett farm. Old man Garrett will help you.

Narrator: Two hours later, Booth and Herold arrived at the farmhouse owned by Richard Garrett, where they were introduced as Confederate soldiers just back from the war.

James L. Swanson, writer: The image of Booth sitting on that front porch, smoking tobacco, playing on the front lawn with the Garrett children, dazzling them with his compass, he seems like he’s relaxed for the first time, that he thinks he can get away. The whole world is hunting for him. There was a frantic pursuit, and here he is, relaxing at the Garrett farm.

Narrator: Unbeknownst to Booth, the federal Cavalry was closing in.

Terry Alford, historian: When the federal pursuers got to the ferry at Port Conway, the wife of the ferryman told them that three Confederate soldiers had taken two men, one with a broken leg across the river. As you could guess the cavalrymen were very, very excited to hear this.

Narrator: That night the Cavalry regiment found one of the Confederate soldiers and forced him to disclose Booth’s whereabouts. At around two am they arrived at the Garrett farm. Booth and Herold were sleeping in an old tobacco barn on the property.

James L. Swanson, writer: Booth and Herold are up by then. The dogs were barking, they could hear the horses coming.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: Booth and Herold are now completely surrounded by Union cavalry and there’s no escape. David Herold wants to surrender and tells Booth he wants out of this now. He sends Herold out who surrenders to the troopers.

James L. Swanson, writer: Booth has certainly concluded by now it’s either escape or death. Unbelievably, he engages the soldiers in negotiation and dialogue.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: He tells Conger and his men to back off a hundred feet, let him come out shooting and they’ll have a standoff. And of course Conger isn’t going to have a standoff with Booth. He wants to take him alive.

Narrator: Finally, at 3am, the detectives ordered the barn to be set on fire. “The blaze lit up the black recesses of the great barn until every wasp’s nest and cobweb was luminous,” a witness remembered. “About the center of the barn, he stopped, drew himself up to his full height and seemed to take in the entire situation. There was a carbine in one hand, a revolver in the other. Suddenly he threw down his carbine, dropped his crutch, raised the revolver and made a spring for the door.”

Terry Alford, historian: As he was coming in their direction a shot rang out. Booth had been shot in the neck by someone and fell to the ground. The doors were flung open, they went in and they grabbed Booth and dragged him outside before the barn caught full fire.

Narrator: A young officer named Boston Corbett had pulled the trigger, later claiming that God had ordered him to do so. The bullet passed through Booth’s neck, severing his spinal cord. “Booth had all the appearance of a dead man,” Lieutenant Conger recalled, “but when I got back to him, his eyes and mouth were moving. I put my ear down close … and finally I understood him to say, “Tell mother I die for my country.”

Gene Smith, writer: Booth is dragged out feet-first from the barn which is crackling in flames. The show is over. The lighting can now be turned out.

Narrator: Booth was laid prostrate on a blanket. With the sun just coming up over the horizon, he managed to utter one, final line.

James L. Swanson, writer: Booth can barely speak. He asks to see his hands. And then he speaks these last words, looking at his hands, “useless, useless.”

Narrator: On May 12th, eight defendants stood trial for the murder of Abraham Lincoln.

Terry Alford, historian: The only person of course who died in the manhunt was Booth. All of his friends were captured and put on trial. And they had to face something in a way even worse than a bullet in the neck; they had to face national scorn, opprobrium and a military trial.

Narrator: Booth’s accomplices — Davey Herold, George Atzerodt, and Lewis Powell — were sentenced to death. Booth’s landlady, Mary Surratt, who had knowledge only of the kidnapping plan, also received a death sentence. The others — O’Laughlen, Arnold and Mudd — were sentenced to life in prison under hard labor. On July 7th, on the grounds of the Old Arsenal Prison in Washington, the four condemned conspirators were led up 13 steps to the gallows.

Edward Steers Jr., writer: The hoods were placed on them; the nooses were fashioned around their necks. The chairs were removed. The executioner gave a signal by clapping his hands three times. The platforms fell and the four condemned conspirators dropped to their death.

Narrator: Booth’s body had been taken back to Washington. Following an inquest, Secretary Stanton ordered the corpse to be buried on the grounds of a federal prison. It was later dug up and reburied in an unmarked grave in the Booth family plot in Baltimore. Rumors swirled around John Wilkes Booth for decades. Many were willing to believe improbable stories: that he had escaped the Garrett barn and gone on to live in Oklahoma, only to die years later, his mummified corpse displayed in a carnival.

James L. Swanson, writer: The historical memory of Booth is that he was the flawed young tragic actor who wrongfully sacrificed his greatness and his life for a cause he held dear. Booth helped perpetrate that because he performed the assassination. He performed the escape. He performed his death. And somehow he transmuted it all into America’s greatest drama. And he’s tricked us into thinking it isn’t all real. It’s too incredible to be real. And so we forget that Lincoln suffered. We forget how his wife and how his children suffered. How the nation suffered.

Narrator: Abraham Lincoln’s body finally reached his hometown of Springfield, Illinois, on May 3rd, his face now so black with decomposition that it was barely recognizable. Mary Lincoln — too grief-stricken to accompany her husband’s casket on its last journey — had insisted that he be buried in a cemetery called Oak Ridge on the outskirts of town. One final funeral procession was mounted, past Lincoln’s home, now draped in black. Under a scorching sun, a thousand people gathered on a hillside overlooking the simple vault that would accept the bodies of Abraham and Willie Lincoln. A Methodist Bishop, Matthew Simpson, gave the final benediction. “More people have gazed on the face of the departed than ever looked upon the face of any other departed man. More have looked upon the procession for 1,600 miles or more – by night and by day – by sunlight, dawn, twilight, and by torchlight than ever before watched a procession. He made all men feel a sense of himself. They saw in him a man whom they believed would do what is right regardless of the consequences. We crown thee as our martyr, and humanity enthrones thee as her triumphant son.”