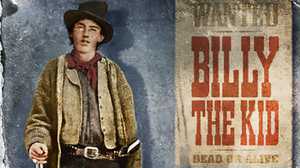

Narrator: On April 28th, 1881, 21-year-old Henry McCarty, alias Billy the Kid, was just days from being hanged for murder. A promised pardon from the governor of New Mexico never materialized and Billy was now in the custody of Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett and two well-armed deputies.

Drew Gomber, Historian: Thursday evening about six o'clock, there's two guards on duty. Pat Garrett went over it time and time again to not be taken in by this guy's charm. I don't care how charming he is, the first chance he gets, he'll kill the both of you and leave.

Mark Gardner, Historian: Billy the Kid was extremely intelligent. He was able to get them to underestimate him time and again.

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: I think he thinks, "somewhere in here, I'm gonna get out of this." Escaping was always on the agenda.

Narrator: Billy the Kid had been on the run from the law since the age of 15. In just a few short years he had become the most wanted man west of the Pecos.

Demonized by a popular press set on cleaning up New Mexico, Billy was portrayed as a blood-thirsty killer, a ''ruthless cuss,'' hell-bent on anarchy.

Michael Wallis, Writer: They were beating the war drums. Let's get rid of that Kid. Let's hunt him down. Let's civilize this territory.

Narrator: Billy the Kid came of age at the moment the myth of the Wild West was forged. At a time when outlaws were made famous overnight in the pages of dime novels, he took his place alongside men like Jessie James, Butch Cassidy and Wyatt Earp.

Denise Chavez, Writer: I grew up with Billy the Kid. We grew up with the myth, the stories. People saw him as a voice for the disenfranchised. He was the Robin Hood of New Mexico.

Gov. Bill Richardson: Billy the Kid was a rebel, an outlaw, good-looking, glamorous. But you have to separate the romantic, mythical side of Billy and the fact that he was a cop killer and that he murdered people.

Fintan O'Toole, Writer: You could actually see in this period in America the formation of something which becomes very, very powerful in 20th century culture, which is the gangster as hero. The idea that the man of violence is the man of action. And that there is no difference really between fame and infamy.

Narrator: The young man who would come to symbolize the freedom and rebellion of the wild west, likely began his life in the teeming slums of New York City. He was born Henry McCarty, the son of Irish immigrants.

His mother, Catherine, had fled Ireland to escape the devastating famine of the 1840s, only to find squalor and hardship in America. It's not known who Henry's father was or how he died but his mother Catherine was determined to give her son a better life than the one she had known.

Shortly after the Civil War, Henry and his mother joined a wave of humanity heading west in search of new opportunity.

Out on the trail, young Henry learned to survive the hardscrabble life of a western pioneer. Catherine made sure he learned to read and write. To pass the time the two sang Irish folk songs as they crossed the vast open spaces of America.

Lured by the promise of silver, 14-year-old Henry and his mother and her new husband, a prospector named William Antrim, settled in the remote outpost of Silver City in Southeastern New Mexico.

By 1873, New Mexico had been a territory of the United States for over two decades but to American settlers fresh off the Santa Fe Trail the region seemed like an exotic foreign country.

Hampton Sides, Writer: The Americans in their journals and diaries, you could sense the kind of a very patronizing and very dismissive of this culture here. The New Mexicans were dark, their religious practices were mysterious. And civilization as we customarily think of it kind of halted here.

Narrator: In the bustling plazas of the capital, traders could be heard bartering for livestock in Spanish, French and Navajo. Rustic dwellings carved into the mesas were home to Pueblo Indians. And Mescalero Apaches continued to roam the countryside.

Denise Chavez, Writer: New Mexico is a place of mestizaje, what we call a mixture of cultures. So you have the Latino Mexican influence, you have the Anglo influence, you have the Native American. It was a wild unbelievable land of great violence and great beauty.

Narrator: Young Henry McCarty was captivated by the world he discovered, instantly embracing New Mexican culture.

He became a familiar presence in the Hispanic district of Silver City known as Chihuahua Hill. In just months he was speaking Spanish fluently. He took to wearing sombreros and beaded moccasins, and he would while away his nights learning to dance the Mexican fandango.

Michael Wallis, Writer: He would go to, into the Mexican district of Silver City with his mother, with Catherine and they'd go to the dances... and they'd dance together. And they'd sing songs together. And he certainly caught the eye of many, many senoritas. These Hispanic mothers and these old aunts and these fathers liked him enough to let him court around and dance with their lovely, protected daughters.

Denise Chavez, Writer: He didn't have his arm out like people might have. He so embraced our culture and our people. He was somebody that was very respectful, very proper. And very formal in a Mexican sort of way which we like, our formality.

Paul Hutton, Historian: He had this, this innate charm. They often talk about sort of his squirrelly teeth and, and how his mouth was shaped, but it was always in a smile. That's what the Hispanic community always says, he was always smiling, always laughing.

Narrator: When Henry was just 15 years old, his mother became gravely ill with tuberculosis. She had hoped that the dry mountain air that banked off the Rockies and settled over the valleys would restore her health, but the Galloping Consumption, as it was then known, proved too much for Catherine. She died in Silver City in 1874.

Mark Gardner, Historian: The Kid is a young teenager when his mom dies. Catherine is his one connection to stability. I mean, this is the mother that's raised you, that's made sure you were fed, that's sent you to school, that's loved you. But once Catherine's gone the stepfather, William Antrim, doesn't seem to really care that much about the upbringing of his stepson.

Paul Hutton, Historian: Antrim abandons the boy. I mean, to be out in this distant and strange land and then to have lost the only connection to who you were and to your past just had to be devastating.

Narrator: An orphan in a tough and transient mining town, it didn't take long for Henry to find trouble or for trouble to find him. In the saloons and brothels in the center of town Henry hustled to make few bucks however he could. At night he would bunk down in the boarding houses with a revolving cast of strangers -- one of them a streetwise petty-thief named Sombrero Jack.

On the afternoon of September 4, 1875, Henry acted as lookout while Sombrero Jack robbed a Chinese laundry. When some of the plunder, including a loaded revolver, was discovered in Henry's room, he was arrested.

Alone in a cramped 4-by-5 jail cell, Henry could hear the bustle of downtown Silver City through the tiny barred window. He knew it might take up to three months for a traveling judge to make it to this part of New Mexico. That was a lifetime to a 16-year-old.

Mark Gardner, Historian: One of the things about the Kid -- he was able to deceive people. He was able to get them to think that he was inconsequential.

Narrator: Henry conned the prison guard into granting him some time outside his cell. When the coast was clear, Henry, no more than 130 pounds with his boots on, forced his tiny frame up the chimney.

Mark Gardner, Historian: The Sheriff returns to the jail and there's no Kid. The cell is empty, the hallway's empty. Probably, it would have been a slap on the wrist had he stayed there -- but with that jailbreak he's a wanted man at the age of 16.

Narrator: Henry decided to head west for Arizona where he hoped to get a fresh start. With no horse, no gun and little money, he was on the run in some of the most hostile land in the country.

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: This country was so bad, so wild, so dangerous, just staying alive was a trick. This was a country where everybody was against you, if you had anything worth taking and you were alone.

Denise Chavez, Writer: This territory, this landscape embraces people who can stand up to the environment, to the harshness, to the desert. And you had to be an unique individual to survive this kind of landscape.

Narrator: After 500 miles of unforgiving desert, Henry arrived at a remote army outpost in Arizona known as Camp Grant, where he stopped running long enough to look for honest work.

Drew Gomber, Historian: Like a lot of kids in his time, he wanted to be a cowboy. You know the whole myth and aura that surrounded cowboys, surrounded them then just as it does now. He wasn't very good at it apparently because the best work he seemed to be able to get was working on the chuck line as a cook. They thought he was too small and frail to be working with the other cowboys.

Narrator: Once again, Henry was back to hustling for money.

He became a skilled gambler and dealer of three card monte and he fell in with a gang of seasoned outlaws who taught him the finer points of stealing horses.

Soon he earned enough to buy the one thing he would need most to survive -- a six shooter.

Mark Gardner, Historian: It's an equalizer. If you want some instant respect, put on a six-shooter, and you're going to get that respect.

Michael Wallis, Writer: He quickly became very good with a gun. He learned how to handle himself because you had to in order to get along out in that raw country.

Narrator: In the year since escaping the Silver City jail, Henry had started to make a name for himself as an outlaw. He had taken to wearing a gambler's ring on his pinky, and brightly colored scarves around his neck. He spent his nights hanging out with other toughs at the raucous saloons where he picked up the nickname ''the Kid.''

On the evening of August 17th, 1877, the Kid danced across a line from which he could never return when he ran into a local thug named Frank Cahill.

Mark Gardner, Historian: Windy Cahill. He's a real boastful, outspoken bully.

Drew Gomber, Historian: He thought it was fun to slap this little guy around, just to amuse the other patrons. And he did that one time too many.

Michael Wallis, Writer: He started really in on the Kid, and one thing led to another and he got him down and was pounding him.

Drew Gomber, Historian: And the Kid was working his hand toward the gun in his belt. And Cahill tried to stop him but couldn't.

Michael Wallis, Writer: Belly shot is not a way to die. It took Cahill all night to die. But by that time the Kid had fled.

Mark Gardner, Historian: Murder is a hanging offense. This is quite a bit different than stealing something from a laundry -- the Kid really has reasons to be afraid of being caught and he's on the run. Even though if he had stayed, there could have been an argument made for self-defense, but the Kid is not willing to take that chance.

Narrator: The Kid had killed a man. He had experienced a quick and fiery baptism from orphan boy to desperado. Now, he could only count on his wits, his gun, and his horse.

N. Scott Momaday, Writer: I think it must have had a profound psychological impact upon Billy, being still young, very impressionable, very vulnerable. You know what does it mean to, to kill a man? I think it further settled Billy into the role of an outlaw. I mean after that, there was no turning back.

Hampton Sides, Writer: New Mexico is a great place to be a fugitive. The distances are so vast and there are so many places to hide, it's a great playground basically for a getaway artist especially if you're friendly with the locals and you speak their language. And you've endeared yourself to them.

Narrator: In 1877, riding a stolen gray mare, the Kid crossed the Arizona border and back into New Mexico. He had changed his name, and was now going by the alias William H. Bonney.

Quietly, he made his way across the territory, catching a meal where he could and relying on the hospitality of the Hispanic farmers whose ranches had dotted the countryside for generations.

But times were changing in New Mexico.

At the end of the civil war, American businessmen had flocked to the territory looking to profit off this vast new land.

The men of this new Anglo establishment quickly became the largest property owners in New Mexico, often wresting land from Hispanic ranchers with the aid of unscrupulous bankers, a rigged legal system, and when all else failed, the business end of a gun.

Michael Wallis, Writer: It was incredible what these people controlled. And they got into the railroading business, into mining, into cattle. Into all of it. But land was at the very cornerstone of their empire.

Narrator: Some of the most lucrative landholdings were in Lincoln County, the largest county in New Mexico. For the past decade, the whole county had been run by tough Irish immigrants Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan. Their business was primarily in cattle ranching and government beef contracts, but there was barely a dollar spent for 30,000 square miles they didn't get a piece of.

Murphy and Dolan's enterprise came to be known as ''The House,'' named for their headquarters -- a giant timber frame building in the town of Lincoln.

Drew Gomber, Historian: The House owned everything in the county and they had pretty much a strangle hold. They had no real competition -- they simply ruled the place like a fiefdom. They were good to their friends but everyone else, you better watch out. You didn't want to get in their way, that's for certain.

Narrator: But someone was getting in their way.

John Tunstall, the 23-year-old son of a wealthy British merchant had recently arrived in town with grand plans to build a cattle empire and seemingly limitless funds to match.

Though he was young and had little experience in ranching, Tunstall knew that competing with the House could get rough.

Paul Hutton, Historian: Tunstall's looking for good cowboys, but cowboys that are not only good with a rope, but also really handy with a pistol and a rifle.

Narrator: The Kid arrived in Lincoln in 1877 and was soon arrested. He was jailed for stealing horses from the Tunstall ranch. But much to the Kid's surprise, instead of pressing charges against him, Tunstall offered him a job.

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: Billy couldn't believe his luck. When he got the chance to go straight, he took it.

Mark Gardner, Historian: One of the things that the Kid says later is that, "Tunstall was the only man that treated me like I was decent and white." He didn't treat him like some riffraff or scum or horse thief. He treated him like a human being. And for someone, a teenager like the Kid, that was a big, big deal.

Narrator: The Kid joined a group of other men, who, like himself, were outsiders. Young men who'd been drifting, trying to scrape together a living out on the plains.

Together they learned how to be proper cowboys. At night they told stories and slept under the stars. Tunstall provided money to keep them in boots and bullets, and most of all, he gave them the promise of a future.

But to Murphy and Dolan, the two Irish immigrants who had enjoyed unfettered power over the county for years, the idea of a well-heeled Englishman moving in on their turf was unthinkable.

Fintan O'Toole, Writer: The first thing you have to remember about both Murphy and Dolan is that they've grown up in rural Ireland. They've experienced what is proportionally still in human history the most deadly famine that there's ever been. And that sort of experience doesn't make people nice. It makes them incredibly ruthless. It gives them an extraordinary other kind of hunger -- it's a hunger never to have this happen to you again.

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: You think they're going to sit still and let this bloody Englishman come in and take it all off them? This is the very kind of Englishmen that's kept our people under their heel and, and ground us into the dirt and made us starve and now he thinks he's going to come out here and take this off us, after what we've had to do to get it? You've got to be kidding me.

Narrator: The House concocted a plan to get rid of Tunstall once and for all.

They enlisted Sheriff William Brady to enforce a phony court order confiscating all of Tunstall's horses and cattle.

On the afternoon of February 18th, 1878, John Tunstall rode into town to challenge the claim on his property. Along the way he ran into the sheriff's posse.

Paul Hutton, Historian: When they find Tunstall, he of course rides forward to talk to them. Here's a man who actually believes that the law will protect him. They never give him a chance. They shoot him out of the saddle. That's the way the law works in Lincoln County.

Drew Gomber, Historian: One of them dismounted, walked over, and put a bullet in Tunstall's head. And then, just out of sheer meanness, they shot Tunstall's horse. They arranged the bodies as though man and horse were taking a nap together. And they put Tunstall's hat under the horse's head and folded Tunstall's coat up underneath his head and they thought it was a good joke.

Narrator: Tunstall's gang of men retrieved his dead body and buried him at his ranch.

The Kid had learned a hard truth about the way the world worked in New Mexico. To him -- Murphy, Dolan, the House and the whole system was corrupt.

He made a pact with with Dick Brewer, Doc Scurlock, and the other men who had worked for Tunstall. Together they would form their own cowboy army. Calling themselves ''the Regulators,'' they vowed to dispense their own brand of justice.

N. Scott Momaday, Writer: Billy had one capacity above others and that was loyalty. He was extremely loyal. He was loyal to everyone who would give him that chance to be loyal. And when Tunstall was killed, he was hell bent on revenge.

Paul Hutton, Historian: He's going to get every man that's been involved in this killing. And he has a particular hit list that he wants to take care of.

Narrator: William Brady, the sheriff of Lincoln County -- the man the Regulators believed ordered Tunstall's murder -- was number one on that list. On April Fool's Day, 1878, they got their chance to even the score.

Mark Gardner, Historian: One day in Lincoln, the Kid is there and several Regulators and Sheriff Brady is walking down the street with several of his deputies.

Paul Hutton, Historian: I think they knew his patterns. They knew he took that morning stroll every day.

Mark Gardner, Historian: And behind an adobe wall the Kid and his fellow Regulators are hiding.

Narrator: The Kid and the Regulators put over a dozen slugs into Sheriff Brady. He was dead before he hit the ground.

Paul Hutton, Historian: It's an assassination, there's no question about it. And certainly, why would they think Brady deserved any better, after he had sent known killers out to murder Tunstall? Brady was a murderer, even though he wore a badge.

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: They shoot him down like a dog, because... you know this is a war. The only way we're going to get a decent law around here is to kill the law we've got and put our law in it.

Narrator: What started off as a revenge killing, sparked by an old world rivalry between the Irish and English, quickly spiraled into anarchy.

The Regulators and the House were engaged in gang warfare, ambushing each other on the countryside, and squaring off in the center of town. With each encounter, the body count rose.

In just a few weeks of fighting the press began calling the conflict ''The Lincoln County War.''

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: The Lincoln County War was the finality of a lot, a lot, a lot of hostility that had been bubbling for a decade. When finally, everybody took arms and said, "Let's finish this."

Narrator: ''It was just an open free-for-all," one former Regulator recalled, ''everyone just had to line up on one side or the other.''

Paul Hutton, Historian: There's a lot of hard feelings going on here. And this isn't unique of course to the Irish and the Englishman, Tunstall. But there's a lot of hard feelings between the Mescaleros and the Hispanics. It doesn't take much to get an argument going and that's why so many dead bodies pile up so quickly.

Drew Gomber, Historian: Law completely broke down in Lincoln County. There was really no semblance of law and order. Every son-of-a-bitch up there wanted to kill somebody.

Narrator: The Kid watched many of his friends die in the relentless violence. Simply by staying alive, he became one of the leaders of the Regulators. In the process, he made a name for himself as a fearsome fighter.

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: The remarkable thing about the Kid -- he's the only one of the soldiers that was in every single skirmish, every fight, every face-off. Every no-you-don't, he was there. And he just kept getting better at it.

Fintan O'Toole, Writer: I think he just gets stuck in the logic of this conflict and I think he does what a young man of his age would have done throughout history, which is he, he fights for the dead, he keeps going because his mates have been killed. It's very, very intense, an incredibly intimate conflict. I think there's a sense that Billy sort of doesn't have anywhere to go. The people he's connected to who, who might have been able to, to help him and might have been able to give him a job or, or get him up the ladder are being killed.

Narrator: Blending into the darkness of the New Mexico night, the Kid could always find comfort and refuge with the Hispanic ranchers. On the tiny sheep farms that surrounded Lincoln, he was becoming a heroic figure in another struggle.

Tony Mares, Writer: The Hispanos would have seen in the Kid a person who was fighting their enemies. The people he was fighting against, even the ones who were on the side of the law, were crooks. The Hispanos knew that. These were not fine outstanding citizens who were being gunned down. He was engaging against people who had stolen a whole country. He was engaging against people who had stolen their lands.

Paul Hutton, Historian: The Kid is a consistent rebel, rebelling against the new Anglo establishment. They are co-opting all the land grants. They are making themselves wealthy. And so when he strikes against the House, he's always striking a blow for those who are being dispossessed, the Mexican sheepherders. So it's not a very long journey to make him into this fighter for justice.

John Michael Rivera, Historian: The Hispanos gave him shelter and hid him. They were able to use the Kid and construct a hero at a time when heroes were on short supply, a time when they had no heroes.

Narrator: Five months after the Tunstall murder, the violence of the Lincoln County War reached its peak. A bloody five-day siege in the center of Lincoln, known as the ''big killing,'' left five more men dead. The Kid narrowly escaped with his life.

To the anxious American politicians and businessmen in the territory, the vigilante violence was bad for business and needed to be stopped.

Indictments were handed down against the Kid and three other Regulators for the killing of Sheriff Brady. Still, the bloodshed continued unabated.

Michael Wallis, Writer: All this murder and mayhem naturally made its way back to Washington and the federal government's response was let's put an end to this.

Narrator: President Rutherford B. Hayes himself intervened, appointing a new governor to the New Mexico Territory, former Union Army General Lew Wallace.

Wallace traveled to the town of Lincoln with a mandate to restore order as quickly as possible.

Drew Gomber, Historian: He came down here and began to take testimony from everybody. He was interested in who killed who and when. And he couldn't get anybody to testify, everybody was frightened. Finally he found a willing witness.

Narrator: In Lew Wallace, the Kid saw an opportunity to clear his name. He wrote a letter to the Governor offering to testify against members of the House in exchange for a full pardon.

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: He's trying not to be on the run. He's trying to go straight. Hey, let's quit this. Let me live a life. Dammit, I'm not 20 years of age yet. I don't want to be dead.

Narrator: Wallace agreed to the deal. And the Kid appeared before a grand jury.

Due in part to his testimony, more than 200 indictments, many for murder, were returned against 50 men, including the House leader Jimmy Dolan.

But when it came time to grant the Kid his pardon, Wallace was nowhere to be found. He had returned to the Governor's mansion in Santa Fe, leaving the Kid's fate in the hands of the authorities in Lincoln.

Michael Wallis, Writer: Basically, I don't think Lew Wallace gave a damn about Billy the Kid. He just wanted to get out of here and get out of here he did.

Narrator: With the Governor gone, the local district attorney, who was a close associate of Murphy and Dolan, dropped most of the charges against members of the House. But indictments against the Kid and the Regulators remained.

Before Billy could be taken back into custody, he slipped out of town.

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: There was a last gathering of the gang, the Regulators, where they all decided to get the heck out of New Mexico. They said, "We're going to Colorado and we're going to Kansas and we're going to Texas, the hell with this." And Billy said, ''Well boys, I'm going to stay here and steal myself a living.'' And he proceeded to do it.

Narrator: The Kid went back to stealing horses and rustling cattle, quickly becoming a nuisance to the wealthy Anglo ranchers in the territory.

Paul Hutton, Historian: The Kid is the consistent rebel all the way. He didn't back down from the House. He's not going to back away now. He is now a real thorn in the power structure in New Mexico. And so they're determined to get him.

Narrator: Over the next few months, newspapers were filled with accounts about the Kid -- mostly embellished. He was portrayed as a murderous villain terrorizing the countryside, a desperate cuss hell-bent on anarchy, in charge of a ruthless gang of criminals. There was scarcely a violent crime committed in the whole of New Mexico that wasn't blamed on the Kid.

Michael Wallis, Writer: The large majority of the territorial press were mouthpieces for the House, for the big bosses up in Santa Fe. They were beating the war drums. Let's civilize this territory. Let's get rid of that Kid. Let's get rid of Billy the Kid.

Narrator: In 1880, an enterprising newspaper editor named J.H. Koogler gave the Kid his most famous alias. Soon, a notice appeared in town squares across the territory: "Wanted, dead or alive, Billy the Kid."

In the spring of 1880, a travelling photographer arrived in Fort Sumner, New Mexico. Dusty and bedraggled, the Kid decided to pose for a 25-cent tintype.

For the past several months, Billy had counted on his close relationship with the Hispanic ranchers in Fort Sumner to help him to elude capture.

It was rumored that he had fallen in love with a 16 year-old Hispanic girl named Paulita Maxwell.

Years later Paulita would say the photo taken that day didn't do him justice.

Denise Chavez, Writer: Paulita would have seen a slim, attractive young man, with dancing eyes, mischievous eyes... Yes, he was scarred. Yes, he was battered, but he was a man who still had his dreams. So she would have seen that great yearning in his spirit.

N. Scott Momaday, Writer: Billy was always looking for a family. He wanted a home and that's the one thing that he never really had and couldn't get. But I think he felt that Fort Sumner was home.

Narrator: A hundred miles away, the town of Lincoln had a new sheriff determined to make a name for himself.

Paul Hutton, Historian: Pat Garrett is a man on the make. He's a man who wants respectability. He wanted to be a famous lawman like Wild Bill Hickock. And in capturing the Kid he could do so.

Narrator: By December of 1880, Garrett had assembled a gang of lawmen. Dubbed the Panhandle Posse, it included some of the toughest cowboys from Texas.

The newspapers would follow their every move, providing details to a public now eager to see Billy the Kid brought to justice.

Mark Gardner, Historian: It's no simple feat. This is winter, this is November, December, when he's out there on the trail. Finally, through a combination of stealth and some sleuthing he tracks him down.

Narrator: Garrett and his posse killed two of Billy's friends, Tom Folliard and Charlie Bowdre, and in just a matter of days they had backed the Kid into a corner in a tiny cabin in a desolate area known as Stinking Spring.

Drew Gomber, Historian: The Kid and the others were trapped inside the place. There was nowhere for them to go. Garrett shot one of their horses right in the doorway.

Narrator: After a night with no food, no water and no fire, the Kid finally ran out of options. He walked out, threw his hands in the air and surrendered.

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: When he came out he said, ''Hell, Pat, I thought you had 200 Texans out here! Otherwise I'd have never given up.'' He's actually going to jail and he's probably going to be hanged and yet he's laughing about it because in here, I think he thinks, somewhere in here, I'm going to get out of this.

Narrator: News of the Kid's capture spread across the territory.

When Garrett arrived in Las Vegas, New Mexico with the Kid in irons, the sheriff was greeted as a conquering hero. Crowds lined the street to see the famous man-hunter and to gawk at the mythic outlaw.

Mark Gardner, Historian: The newspaper reporters are allowed in and they get to talk to the Kid. And as he's talking to the reporters, the Kid says, ''you know, this is good, maybe people will think I'm half-human now, because they haven't thought I was human before. They considered me an animal, maybe now they'll think I'm half-human.''

Narrator: ''He did look human indeed...'' one reporter wrote, ''there was nothing very mannish about him in his appearance for he looked and acted like a school boy, with the traditional silky fuzz on his upper lip, and clear blue eyes with a roguish snap about them.''

Billy was loaded onto a train, bound for Santa Fe where he would await his trial for murder. As he pulled away from the station, the defiant Kid smiled and laughed, inviting reporters to come visit him in jail.

Paul Hutton, Historian: The train of course is the machine in the garden, the change that's going to come to the entire west. And so now he is of course placed on this machine. And now it's going to take him to Santa Fe and there of course they'll chain him and they'll prepare him for execution. Once he's on that train, it's a one-way trip.

Narrator: Billy was convicted of first-degree murder for the killing of Sheriff Brady.

He was sent back to Lincoln in the custody of Pat Garrett and two well-armed deputies, J.W Bell and Bob Ollinger. At only 21 years of age he was a dead man walking -- scheduled to hang in just a matter of days.

N. Scott Momaday, Writer: He believed that he was going to get away. All he had to do was recognize the opportunity.

Michael Wallis, Writer: It was a matter of time and he... and he picked his time well.

Narrator: On the afternoon of April 28th, 1881, Garrett was out of town on county business and Bob Ollinger was across the street eating dinner.

Mark Gardner, Historian: The Kid said, ''I need to go use the outhouse.'' Bell takes the kid out to the outhouse, they come back in, and at the top of the stairs, he surprises Bell. Billy gets Bell's gun, and Bell panics and he starts running down the stairs, and he does inflict one mortal wound. Billy grabs Bob Ollinger's shotgun, and he runs to one of the windows where he could see out across the street. Because he expected that Ollinger probably heard the gunfire.

N. Scott Momaday, Writer: And Ollinger -- I've always imagined him picking up his head and saying, "Did you hear, did you hear that, did you hear something? It's a shot." And so I don't know what was going on in his mind, but he must have known something like fear, real fear.

Paul Hutton, Historian: And Ollinger came running across from the Wortley and someone yelled out, ''The Kid's killed Bell!''

Mark Gardner, Historian: And just as soon as Goss spoke those words, Ollinger hears the voice from above in the window...

Paul Hutton, Historian: Hello Bob.

Drew Gomber, Historian: Hello Bob.

Mark Gardner, Historian: Hello Bob.

Paul Hutton, Historian: And Ollinger looked up into the twin barrels of his own shotgun.

Drew Gomber, Historian: He's hit by 36 buckshot, which is about a quarter pound of lead. He's dead when he hits the ground.

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: It is so unexpected -- he's got no chances of getting out of this, and suddenly and then whip, whap, bang -- they're dead and dead very spectacularly. And he then comes out, commandeers a horse, and rides out of town singing.

N. Scott Momaday, Writer: He was very good at getting away -- escaping. Escape was one of his great talents. In that moment when he leaves the courthouse on horseback... as he goes out of sight, he passes into legend at that moment. The story will never be the same after that.

Narrator: The story would take less than a day to make front-page headlines across the country. The telegraph gave electric life to the details of Billy's escape.

Gov. Bill Richardson: He became nationally famous 'cause instantaneously, people would know about Billy and what he did, and, and he was glamorized. And he was made into a mythical character.

Fredrick Nolan, Historian: The New York Times, he was even in the London Times... big towns, small towns, Fredericksburg, Illinois. Name any town you like. Chicago, sure. San Francisco, certainly. He became an absolute icon of American outlawry.

Narrator: Just a few years earlier he had been a skinny orphan boy from New York City. Now, Billy was the most feared man in New Mexico.

He knew it wouldn't be long before someone came looking for him, but he still refused to leave the territory.

Tony Mares, Writer: He was urged to by friends. To you, you know, don't let the sun set on you in New Mexico. He made no attempt to get away and he could have.

Michael Wallis, Writer: Most of us know exactly why he did that in two words -- Paulita Maxwell -- his true love. He wasn't going to go down to Mexico. That would have been the smart thing to do. But you know sometimes a kid isn't always smart. Sometimes the heart rules, and I think it certainly did in that case.

Narrator: It had been nearly three months since Billy escaped from Lincoln. Some began to wonder if Pat Garrett was too afraid to go after him again. But Garrett was biding his time and he knew exactly where Billy was.

Drew Gomber, Historian: You know, Pat Garrett kept getting these persistent tips from Fort Sumner that the Kid was up there. Turned out the tips were coming from Pete Maxwell, Paulita's big brother, who did not approve of their relationship. And finally Garrett decided that he had to act on it.

Narrator: Garrett and two new deputies headed up north along the Pecos River. They arrived in Fort Sumner the night of July 14th, 1881, and went directly to the Maxwell home.

Garrett posted his two men on the front porch. So as not to be noticed, he snuck in through the back and found his way to Pete Maxwell's bedroom.

At that same moment, Billy in his stocking feet approached the porch where Garrett's men were stationed.

N. Scott Momaday, Writer: Billy came to Maxwell's house in the dead of night, presumably to cut a piece of meat from a beef that was hanging on the porch.

Michael Wallis, Writer: He came up, he saw those two silhouettes there hunkered down, and he asked them in Spanish, ''Quién es? Quién es? Who is it?'' There was no answer.

Drew Gomber, Historian: Well the Kid backs away from them and backs away from them and finally, backs into the doorway. And from inside the room, he's framed in the light, the moonlight. And Garrett is sitting on the bed with Pete Maxwell. Maxwell leaned over and said, "El es." It's him.

Michael Wallis, Writer: It's him -- and Garrett took his gun and blasted.

And there fell dead Billy the Kid. Right on that floor with that question on his lips, ''Quién es?'' Never knowing who killed him.

Paul Hutton, Historian: The folks in the local community are horrified by what's happened. The local senoritas and Paulita Maxwell gather up Billy's body. They anoint him and lay him out and sort of pray over him that night. They loved the Kid.

Denise Chavez, Writer: New Mexicans felt that he is one of us, Lo nuestro. One of ours.

Narrator: News of his killing spread fast.

Everyone from preachers in pulpits to kids in the schoolyards retold story of how legendary outlaw Billy the Kid was gunned down.

Michael Wallis, Writer: My maternal grandmother, she would tell me of that day when her brothers ran into the house in Kansas City, Missouri and said, ''Two days ago, out in New Mexico territory, they killed Billy the Kid!'' She remembered that day as clear as a bell when she was an old, old woman and I think a lot of people did.

Narrator: For killing Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett would enjoy momentary fame as America's greatest lawman. But in 1908, mired in gambling debts, he was mysteriously shot dead along a remote stretch of road in the New Mexican desert.

For the big business men in Santa Fe, economic progress was slow to come to the territory, and they would have to wait another 30 years for statehood. The House and its beef empire would go bankrupt and the names Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan would fade from memory.

Only the Legend of Billy the Kid would endure.

Michael Wallis, Writer: That was Henry McCarty that died, that was Billy Bonney that died. Billy the Kid rode on and he rides on forever...