Narrator: It was, as one newspaper noted, a diabolical act “unparalleled in the annals of terrorism.” On September 16, 1920, as the bells of Trinity Church tolled and hundreds of Wall Street as workers headed out for their noontime break, an explosion struck outside the headquarters of J.P. Morgan and Company—the world’s most powerful banking institution.

Bruce Watson Writer: The bomb broke windows. It knocked trolley cars off their tracks two blocks away. It ignited curtains 12 stories in the air. It was just a savage, horrifying thing.

Beverly Gage, Author, The Day Wall Street Exploded: People fled their places of work gage and they saw basically a war zone.

James Green, Historian: This was an attack on civilians just for the sole purpose of creating terror.

Narrator: The blast left 38 dead and hundreds more seriously injured. Striking at the heart of the nation’s financial center, many wondered if this was the spectacular blow against capitalism that radical agitators had so long discussed.

Beverly Gage, Author: The corner of Wall and Broad Streets represented the fusion of American capitalism with American government. You could target them both at once.

Steve Fraser, Historian: To target it is to say, “We are taking on the citadel of American capitalism. We, we loathe it. We wanna overthrow it.

Narrator: Financial centers around the country went on high alert, and he head of the Morgan Bank sent guards to his family’s Madison Avenue residence.

As federal troops arrived to protect the nearby US Sub-Treasury building, investigators sifted through the rubble for clues.

James Green, Historian: It’s not at all clear who… might be responsible. So many people out there had a grudge against Wall Street that people wondered, “Well, it could be any, any one of these forces. And that increased the anxiety even more.”

Narrator: Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer arrived on the scene and told reporters the explosion on Wall Street was the terrorist attack he had warned Americans about. For more than a year, in the tumultuous aftermath of World War I, he had been at the center of a bitter national debate about how far the government should go to protect the nation from acts of political violence.

Palmer pointed to the carnage on Wall Street as proof of the need for renewing aggressive action.

Beverly Gage, Author: It’s easy to think about terrorism as this frightening plague of the early 21st century. The Wall Street bombing suggests that it actually has a much longer and deeper history. How widespread government surveillance ought to be, what kinds of policies are justified in containing a threat. Those questions were being opening asked in 1920.

Narrator: In January 1919, ships carrying thousands of soldiers home from World War I sailed into New York Harbor.

Filled with hopes for a better future, the troops were greeted by cheering crowds eager to leave behind the horrors of a brutal war that had left sixteen million dead.

Returning soldiers had reason to feel optimistic about the economic opportunities ahead. Corporate profits had tripled and stock prices had boomed during the war, helping to create forty-two thousand new millionaires.

Beverly Gage, Author: World War I really was a watershed moment in terms of the American economy, The United States, for the first time, is a creditor nation so Europe owes the United States more money than the United States owes to Europe. This is a big coming-of-age moment.

Narrator: Profitable though it proved to be, the war created economic and political divisions that threatened to derail dreams of postwar peace and prosperity.

Steve Fraser, Historian: While the American economy in general benefited from the war, the chief beneficiary was the financial establishment centered in New York.

James Green, Historian: There was some pent up frustration about the fortunes that had been accumulated during the war. There was this sense that it was a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight. There was also the bitter legacy of the repression that occurred under the Sedition Act and the Espionage Act.

Narrator: Shortly after American entry into World War I, President Wilson had signed espionage and sedition laws which made it a federal crime to speak out against the government or the war. The legislation was an unprecedented regulation of free speech that sent thousands to jail, and fostered an atmosphere of suspicion.

Charles McCormick, Historian: [Americans [were] schooled throughout the entire war in being afraid of things, in being afraid of foreigners, in being afraid of German spies, in being afraid of anyone who wasn’t sort of like the majority, which was essentially white Anglo-Saxon and Protestant.

Bruce Watson, Writer: The President, spoke against hyphenated Americans. You shouldn’t call yourself German-Americans, or any other type of hyphenated American. the war really ratcheted up that sense of, of American patriotism—jingoism, if you wanna call it that

Narrator: By early 1919, Americans conditioned to fear Germans were focusing their anxieties on a new global threat: Vladimir Lenin and the Bolshevik revolutionaries who had seized power in Russia to form a communist state.

Beverly Gage, Author: The Bolshevik Revolution was the world’s first successful anti-capitalist revolution in which it appeared that the working class had risen up, and overthrown its masters, and put something very, very different in its place.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: it was much bigger than something that happened in Russia. It was… followed by a series of Left Wing uprisings right after World War I in Germany, in Hungary, in Italy, in Argentina, in other countries around the world. For that moment in 1919 the world was really in play. These countries were in play.

Beverly Gage, Author: Lenin comes out and says, “We want the workers to take over the world.” And you begin to see glimmers of this happening in the United States.

Narrator: On February 5, 1919 Seattle’s mayor Ole Hanson sent an urgent message to the US Secretary of War: the entire city of Seattle was about to be shut down in the first general labor strike in U.S. history.

Narrator: The strike began two weeks earlier. Thirty-five thousand shipyard workers had walked off the job demanding higher wages to cope with rising living costs.

James Green, Historian: From the point of view of workers this was their time, they had sacrificed so much for the war, including their wages and they had seen their employers’ gain when they fell behind.

Narrator: In an unprecedented show of solidarity twenty-five thousand workers from other unions joined the walkout.

Bruce Watson Writer: The entire city was shut down for a few days. The trolleys did not run. Other industries did not show up to work, etc., and of course this really alarmed the powers that be.

James Green, Historian: It raised a specter of what organized labor could accomplish and it was scary to a lot of people.

Narrator: In the weeks leading up to the strike, pamphlets about the Russian revolution circulated widely among Seattle’s workers. “The Russians have shown you the way out,” they read. “What are you going to do about it?”

The strike was peaceful and orderly, but Mayor Hanson, viewed it as the opening shot in an attempted Communist revolution.

Alternate: The strike was peaceful and orderly, but Mayor Hanson viewed it as an attempted communist revolution intent, he said, on “the overthrow of the industrial system; here first then everywhere.”

Seattle’s residents braced for civil war, and a local newspaper blamed the “riff raff of Europe” among the workers for starting it.

Narrator: Hanson threatened martial law then summoned federal troops to end the strike less than a week after it began.

"The time has come," he said, "for the people in Seattle to show their Americanism.”

Hanson became a minor celebrity for his strong stand. He soon embarked on a lucrative national speaking tour to warn of the foreign agitators threatening the nation.

His speeches stoked fear among those already unsettled by the strikes rippling across the country.

Almost four million men and women, would join the picket line in the coming year—an average of over 200 strikes a month—threatening to shut down the nation’s vital industries.

Beverly Gage, Author: You see a really wide range of demands, and you also see a new kind of revolutionary language taking hold.

James Green, Historian: Workers were questioning the validity of private ownership of industry. “Let’s let the government keep running the railroads. Let’s nationalize the mines. And it really frightens people in the context of believing that somebody might be manipulating them.

Narrator: In the wake of the Seattle strike, Congress opened hearings on the communist threat. They debated laws banning immigration and revolutionary speech. And then waited to see if the Justice department would take any action.

The new Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer didn’t want mounting hysteria about the red threat to set his course at the Justice Department. The former Pennsylvania congressman was more interested in promoting the progressive ideals on which he’d built his political career.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: He was a Democrat on the liberal fringe of the party. When he was in Congress he introduced legislation to give women the right to vote, to end child labor, to support labor unions. Wilson appointed him Attorney General not to impose any kind of crackdown against radicals but because he would be helpful in defusing the tensions that existed during the war.

Narrator: Some of the President’s closest advisors dismissed Palmer as a political opportunist with an eye on the oval office. Wilson considered him a loyal ally. In his first term, he offered Palmer the job of Secretary of War. Palmer turned him down, claiming it would violate his religious principles as a Quaker.

He later served the war effort by overseeing the seizure and sale of German-owned assets in America.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: He, he had a very good talent for making headlines. It threw him in the limelight and by the end of the war he was a real celebrity

Beverly Gage, Author: He acquired a nickname, “The Fighting Quaker,” because he was fighting on behalf of America and that was sort of how he was known at the moment that he became Attorney General.

Narrator: In his first weeks on the job, Palmer signaled a shift from the repressive wartime policies of his predecessor.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: Some of the first things he did were to free about 50 people who had been jailed under the Espionage Act. He disbanded the American Protective League, which was a vigilante group created during the war to crack down on slackers and spies. So everything had him acting as a moderating influence.

Narrator: Investigators were impressed by the bomb’s cunning design—a wooden tube filed with an acid detonator and dynamite.

Narrator: Concealed in a gift box, the bomb arrived at the office of Seattle’s Mayor Ole Hanson in late April 1919. An aide to Hanson opened the package, but it failed to detonate. An identical box delivered to the Georgia home of a former US Senator blew off the hands of the maid who opened it.

In the coming days, federal investigators would discover 28 more bombs making their way through the US mail, all timed to arrive on May Day, the international day of solidarity for radical political groups.

The intended recipients included six Congressman, three cabinet members, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, and the nation’s preeminent banker J.P. Morgan, Jr.

Bruce Watson Writer: The targets were very, very prominent capitalists, and others who had specifically targeted radicals. It was a sinister, and very well-planned plot.

Narrator: One of the packages was addressed to Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer.

Beverly Gage, Author: this is an enormous scare and people begin to think, “Is there an organized conspiracy for revolution in the United States and are there more bombs on the way?”

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: [IT] gave the im-impression to, to the country that the radical fringe was escalating the violence to an unacceptable level.

Although most of the bombs never reached their destination, newspapers urged Americans to call police before opening any suspicious packages. Citizens already on edge lashed out.

Narrator: Riots erupted when mobs attacked May Day rallies in cities across the country.

Ole Hanson went on the offensive, criticizing Palmer for his “weak” response to the threat at hand.

“I hope Washington will buck up and hang or incarcerate for life all the anarchists in the country,” he told crowds.

Palmer held firm. He pledged he would treat the mail bombs as a criminal investigation and no more. He ordered the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation to draw up a list of suspects, then left the case in the hands of the post office inspectors.

Palmer wouldn’t be able to remain on the sidelines for long.

Beverly Gage, Author: We tend to think of the late 19th and 20th century as being a kind of triumphal age. What’s emerging during this period are whole new sets of ideas about what’s wrong with capitalism. Some of that came out of the organized labor movement. Some of it came even further to the Left, groups like anarchists and Socialists who really did think that capitalism needed to be overthrown, done away with all together.

Steve Fraser, Historian: people were deeply anti-capitalist because it had destroyed lives of all kinds. Capitalism is a kind of curse, and the people therefore who run it are seen as bestial, as depraved, as inhuman, as consonantly greedy.

Narrator: Since the early 1900’s, labor and revolutionary groups had argued about how best to challenge the economic inequities of capitalism---whether change would come through votes or violence.

Beverly Gage, Author: there’s a huge range of opinion about whether revolution is gonna be something that comes in people’s hearts and minds, or whether you’re literally talking about an armed uprising. You see lots of people saying. What democracy means is that you can run candidates for office. That is how you make change. And then you have a small number of people who say terrorism is a useful tool in this whole story.

Narrator: Anarchists had been among the first to advocate dramatic acts of violence as a political weapon.

Bruce Watson Writer: anarchism has many different branches. Again, there were the pacifists. There were the syndicalists, there were others. And among them were a group of people who believed in what was called the “propaganda of the deed,” and the deed was violence.

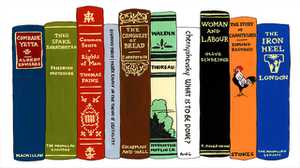

Narrator: One of the most prominent proponents of propaganda by deed was a charismatic Italian anarchist named Luigi Galleani. His followers numbered in the thousands, the vast majority of them immigrant manual laborers.

Bruce Watson Writer: He was amazingly eloquent, and he spoke to groups of people in, in gatherings in labor groups, and, and Italian enclaves all throughout the East Coast.

And he wrote books as well. One of his books was called La Salute e in Voi, which in Italian means, “The Health is Within You,” which sounds like a nice peaceful thing. It’s actually a dynamiting manual and how to use dynamite effectively.

Narrator: For more than a decade, Galleani had published an Italian language weekly called Cronaca Sovversiva – Subversive Chronicle—which attacked the state and private property owners. Galleani’s feelings about the government were clear. “Overthrow it,” he wrote “make the country free forever with the triumph of true democracy made by Americans, not by Wall Street.”

Bruce Watson Writer: It was a truly incendiary rag. The Bureau of Investigation discovered this… publication during World War I and quickly put it on the banned list of periodicals. The Bureau confiscated lists of subscribers and immediately targeted all of them as radicals to be watched.

Narrator: Bureau agents also raided Galleani’s home, gathering evidence that immigration authorities would use to deport him in June 1919.

As he prepared to leave the country Galleani urged his followers to seek revenge against the tyrannical federal government.

Shortly after 11:00 pm on June 2, just a month after the May Day plot, police arriving at the Washington DC home of A. Mitchell Palmer encountered a disturbing scene: a bomb had exploded on the attorney general’s doorstep-- detonating prematurely as the bomber was delivering the device.

Bruce Watson Writer: It was really just a… huge, mind-ripping explosion. They saw the remains of this man blown all over the neighborhood. There were pieces of-, there were limbs, and blood on the trees, And it was just a shocking violation.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: A few minutes earlier he and his wife had been sitting in the library downstairs. If they had waited a few minutes longer before going upstairs they would’ve been dead.

Narrator: Palmer soon learned of midnight bombings in six other cities, most at the homes of anti-radical judges and legislators.

Beverly Gage, Author: unlike the May Day bombs, which conceivably could’ve all been put together and mailed by a single person, it’s quite clear that there’s no single person who could have set off bombs in Washington, and Boston, and New York, and several other cities at the same time. So it’s clear that there is some sort of organized conspiracy.

Narrator: Found among the wreckage of Palmer’s home was a flyer promising more violence.

Bruce Watson Writer: The flyer was a masterpiece of rage and eloquent militance. It brooked no, no uncertainty at all about what was coming. It said, “There will have to be murder. We will kill. It said the powers that be had provoked this. It ended with, “Long live the revolution,” and it was signed, “Anarchist Fighters.”

Beverly Gage, Author: you can imagine it terrified [PALMER] and in some sense it actually radicalized him on the question of, “What are we going to do about people who are advocating revolution in the United States.”

Narrator: The evidence scattered across Palmer’s lawn pointed to Galleani’s followers. But Palmer didn’t limit his next move to hunting down the bombers. He used the June attack to launch a broader campaign against all revolutionary organizations.

Narrator: Warning the next attack could come within weeks, Palmer told Congress what he needed to prevent it: emergency funding for the Justice Department to investigate and deport what he described as the “alien troublemakers” threatening to overthrow the government.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: What they decided to do was not to wait for another violent outbreak but to launch something of a preemptive strike to try to get as many radicals as they could off the streets and to the extent they could out of the country.

Scene 3: J. Edgar Hoover and the birth of peacetime surveillance

Narrator: Palmer created a new domestic intelligence unit within the Bureau of Investigation to keep tabs on potential threats.

It was called the Radical Division.

Beverly Gage, Author: this was a transformative moment. You had never had the federal government coming forth in quite such a concerted way to say, “We’re going to keep track of political movement, political groups, radical organizations within the United States during time of peace because they actually pose a threat to the national order.”

Palmer’s choice to run the new unit was an ambitious 24-year old justice department lawyer named J. Edgar Hoover.

Charles McCormick, Historian: He was a bright young man, who stuck to the rules, much committed to Protestantism, and he was very good at organizing. Hoover read everything he could get his hands on on the Communists, and became firmly convinced that they were the greatest threat that existed.

Narrator: Hoover had put himself through law school by working as a clerk at the Library of Congress, mastering its complex classification system. He began his legal career identifying politically suspect foreigners during World War I.

Beverly Gage, Author: He takes what he’s learned at the Library of Congress, he takes what he learned processing Germans during the war, and he sets up what is effectively the first really mass, peacetime political surveillance filing system in the United States

Narrator: Hoover built his database from a vast array of sources, including military intelligence, postmasters, and private detectives. He hired translators to monitor radical publications and planted undercover informants inside labor unions.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: He was setting up a system to keep track literally of every identified radical in the country, who they talked to, where they lived, what organizations they belonged to.

Beverly Gage, Author: You didn’t need very much to become a target of the Bureau of Investigation. All you had to do was show up in the orbit of some kind of radical or labor demonstration, or criticize the Justice Department.

In its first year of operation, the Division would amass more than 200,000 files on radical activities.

Narrator: The Justice Department’s careful preparation did little to ease the fears of Americans who saw revolution in the labor unrest sweeping the country.

In September, just weeks after the formation of the first American Communist parties, steelworkers nationwide walked off the job. Coal and railway workers also threatened a shutdown. The walkout of three-fourths of the police department in Boston threw the city into chaos.

James Green, Historian: They were branded as Bolsheviks because it was inconceivable that they could have done this on their own.

Steve Fraser, Historian: everything //feeds this kind of atmosphere of hysteria that agitators, Red agitators are stirring up people to engage in this kind of social disorder, this kind of violent behavior so people feel they’re living on the edge

Letters calling for government action flooded Congress. Senators demanded Palmer explain why he had not yet taken action against those attempting to “bring about the forcible overthrow of the government.”

Narrator: On November 7, 1919, Palmer silenced his critics. He launched a raid on the second anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution to send a message that America was fighting back against communist influence.

With Hoover serving as the point man in Washington, agents arrested several hundred members of a group he had been monitoring---the Union of Russian Workers.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: They invited the press to be there to watch… it was a quite violent affair designed as much for political effect and for theater as, as well as actual breaking up of the, of these radical organizations

Narrator: Hoover commandeered an army transport ship to carry 249 detainees back to Russia. In a headline-grabbing move he included two of the nation’s most notorious anarchists, Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. Their celebrity overshadowed the fact that most of the detainees had never been part of a criminal or terrorist act.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: you could call it a publicity stunt but it was a very major action. They sent the Russians back where they belong. That’s how it was portrayed.

Bruce Watson, Writer: The Palmer Raids, for all their terror were really cathartic in the sense that it sort of made most Americans think, “Well, we’ve handled those people and we’re not gonna hear much from them anymore.”

As the deportees left New York Harbor on December 21st, reporters claimed their shouts of “long live the revolution in America” could be heard on shore.

Newspapers celebrated Palmer for taking action.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: Palmer was viewed as a strong leader, who in the midst of chaos was taking, drawing a firm line. He recognized this as a boon and he very shortly would start organizing a campaign for President of the United States.

Narrator: Promising “no let up,” the Attorney General authorized Hoover to move forward with plans for a massive raid just after the New Year.

On the night of January 2, 1920, Palmer’s agents struck simultaneously in 33 cities across the country. Raiding parties swept through meeting halls and private homes, arresting everyone in sight.

They seized nearly five thousand people for deportation—many were American citizens and didn’t even belong to any of the targeted radical groups.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: Hoover was receiving telegrams, and phone calls, and messages by the hundreds. Every time there was a legal question a logistical problem, it would first go to Hoover.

Bruce Watson Writer: Hoover pretty much ran what are now called the Palmer Raids, but might easily be called the Hoover Raids.

Narrator: With support from local police, federal agents herded suspected radicals into detention centers, searched their homes and confiscated their possessions.

Bruce Watson Writer: Thousands of people were detained without any warrant, without any, without any specific cause, and they were kept for a weeks at a time. Some were beaten.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: They had no prisons big enough to hold all of these people. In, Detroit, they put about seven or 800 people in a corridor of a government office building with just one bathroom, a water fountain, and held them there for seven or eight days 'cause they had no place else to put them. In Boston a person committed suicide cause the conditions were so bad.

James Green, Historian: It sent a real terrifying message through the immigrant community. And I think for the anarchists in particular this was… the final…evidence that the American government had declared war on their people.

Narrator: Soon, it wasn’t just radicals that thought Palmer had gone too far.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: The evidence started coming out about just how thin these cases were, The fact that very few of these people had any connection with violence or real radicalism, a real threat to the country.

Narrator: Church, labor and business groups began questioning Palmer’s tactics—which had failed to produce the May and June bombers or evidence of a future plot. Even within Palmer’s own Justice Department there was criticism.

On January 12, US Attorney Francis Fisher Kane resigned from office in protest. “We appear to be attempting to repress a political party,” he wrote to Palmer. “By such methods we shall drive underground and make dangerous what was not dangerous before.”

Beverly Gage, Author: you’ve taken people whose opinions you don’t like, who have joined organizations that you don’t like, and you’ve arrested them en masse, without ever having a court proceeding. Are these people really a threat or are they not a threat, and how are we going to assess that? You get a really big set of questions about what kind of country do we actually want to be.

Narrator: In the coming months, Palmer’s critics gained momentum. The acting Secretary of Labor nullified more than two thousand deportation warrants, calling the evidence against the deportees “flimsy.”

Palmer tried to focus public attention on the red threat, claiming again that he had received intelligence warning of a revolutionary upheaval on May 1st.

When the day passed peacefully, Palmer was ridiculed for being an alarmist.

Narrator: A month later, a damning report by twelve prominent lawyers accused the Attorney General of “utterly illegal acts…which have struck at the foundation of American free institutions.” Congress summoned him to Capital Hill to defend his deportation raids.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: At the end of it Palmer is very frustrated. He saw the country call on him, demand him to take this hard line and he did what he thought was his responsibility with the information he had before him. The hard part though is figuring out how you come up with something that addresses the threat, that doesn’t at the same time do the collateral damage of, of sweeping up innocent people who’ve done nothing to deserve it.

Narrator: Palmer still hoped he had enough support to win his party’s presidential nomination, but when he arrived in San Francisco to appear before the delegates in July 1920, even his close friends regarded him as poor presidential material. The press wrote off the nation’s “fighting Quaker” as the “quaking fighter.”

By the time Palmer left the convention in defeat, hysteria-weary Americans were embracing the Republican nominee Warren Harding. His campaign dismissed the radical threat and promised to return America to ‘normalcy.’

On September 16, 1920 the stock market was having a bullish day, reason for optimism after bumpy summer.

Inside the Morgan bank, a partner was wrapping up a meeting with the owner of one of the country’s largest mining operations about the latest round of strikes in the Pennsylvania coalfields.

Across the street, government workers were busy transferring a billion dollars in gold to the Sub-Treasury.

A few minutes before noon, as lunchtime crowds began to fill Wall Street, a postal worker discovered five flyers stuffed inside a mailbox just a short walk from the bank.

As the bells of Trinity church began to toll, he read the alarming words.

Moments later, a violent blast rocked the financial district.

Narrator: It began with a flash, then a roar—followed by a force so powerful, that skyscrapers three blocks north trembled from the impact.

Fire-packed air smashed against buildings, and burned though the lunch crowd, leaving devastation in its wake.

Steve Fraser, Historian: There’s pandemonium everywhere. The brokers on the Stock Exchange think the glass dome atop the Exchange is gonna collapse. Trinity Church is shaken to its foundations. It’s a terrifying… scene.

Bruce Watson Writer: When people came out from the trading floor they could still see a mushroom cloud rising above Wall Street. It was hundreds of pounds of dynamite packed into a horse cart and when it went off it just tore people in half.

Narrator: Bodies mangled beyond description sprawled amidst the shattered glass. The remains of a man lay in front of the Morgan bank—the building’s pale granite walls stained with splotches of red.

Beverly Gage, Author: All through the district were these little pieces of metal that were window weights and they had been packed around the explosives. Many people died from, from lung injuries, from internal bleeding as these weights entered and penetrated their internal organs.

Narrator: Most of the dead were under the age of thirty and made a modest living serving the trading houses of Wall Street.

Beverly Gage, Author: If you set a bomb at the corner of Wall and Broad Streets the assumption was you were aiming for the biggest men of American capitalism. But that’s not who this bombing hit at all. It really impacted ordinary people.

Narrator: As news of the tragedy spread, stock exchanges from Boston to San Francisco suspended business. Eager to minimize further damage to the nation’s financial markets, Wall Street leaders moved quickly to reopen the stock exchange for business the next day.

Crews worked feverishly throughout the night to clean up the shattered glass and hose down the bloodstained streets.

Beverly Gage, Author: Wall Street’s answer to the bombing is to get back to what they described as “business as usual” and to put on a real show of, of defiance and strength.

Narrator: At noon the next day, more than a hundred thousand descended on Wall Street for a previously scheduled celebration of the signing of the Constitution. They gathered at the spot where George Washington first took the oath of office, his unscathed statue just steps from the epicenter of the blast.

The mixed emotions of the day were on full display. The solemn crowd listened to a prayer for national safety and a speech calling for the capture and killing of the bombers, before singing a rousing rendition of the national anthem.

Attorney General Palmer was quick to point out that he might have been able to prevent the attack if Congress hadn’t slashed his budget in the backlash against his raids. He called for a new deportation campaign and vowed to ram a peacetime sedition bill through Congress.

Beverly Gage, Author: On the day after the bombing Palmer stood there. He said, I warned you that something like this was going to happen and here it is. We need more raids. We need more aggressive action against the people who clearly did this.”

Narrator: Palmer found wide support for his ideas in the national press and business community. But other voices were more cautious. “By what means are we to face lethal attempts to overthrow the established order,” one newspaper asked. “There must be no yielding to fear.”

Beverly Gage, Author: a lot of people stepped up in that moment and said, //we’ll get the person who set off the bomb on Wall Street. We will try them in court and we will send them to prison. But we don’t need to go after entire groups of innocent people just because they share certain political opinions.

Narrator: Finding the person who set off the bomb proved difficult.

After sifting through tons of debris, investigators confirmed the bomb had been planted on a horse drawn cart. But they were unable to identify the driver.

With the followers of Luigi Galleani considered prime suspects, agents scoured Italian neighborhoods for leads. They traveled to Italy to track down the deported Galleani himself. Like many other suspected conspirators, he was nowhere to be found.

Focus shifted to Russia, where Hoover sent undercover operatives to find proof that Lenin’s communists were behind the attack.

After three years, officials had little to show for their efforts but an embarrassing string of false arrests. The trail had gone cold.

Beverly Gage, Author: Probably the best theory that we have suggests that the bomb was actually set by a man named Mario Buda, who was, in fact, an Italian anarchist who moved in the circle around Luigi Galleani. And Buda’s act was a protest against the arrests and deportations of Italian radicals as a whole.

Bruce Watson, Writer: Buda disappeared. He later turned up in Italy. People went and talked to him, etc. He never admitted anything like this but then again you never know who to believe when you are talking to anarchists

Narrator: As anniversaries of the Wall Street bombing came and went, fewer Americans seemed to notice the case had not been solved.

Beverly Gage, Author: It is the Roaring Twenties. It is a time of triumphal celebration of Wall Street as an icon of American success and prosperity, and somehow this bombing just seems very quickly like the last gasp of an older much more conflict-ridden age.

Steve Fraser, Historian: Wall Street bombing is the culminating point of a long period of anti-capitalism that… engaged American culture, and politics, and economic life for well more than half a century. But the bombing… put an end to that this act of terrorism was rather than a kind of reveille for radicals, it was kind of their final last gasp.

Narrator: By 1924, A. Mitchell Palmer, the man who had led the war against radicals in America, was no longer a political force, but his sweeping deportation campaigns had achieved many of their aims.

Kenneth Ackerman, Writer: The heavy-handed tactics of the officials had really just scared the hell out of anyone who thought of joining the movement.

Beverly Gage, Author: The Communist Party goes underground. The anarchist community never again has the kind of presence in American politics and culture that it did in the teens.

Narrator: J. Edgar Hoover did his best to distance himself from the deportation raids. He claimed Palmer alone had been calling the shots.

Hoover relied on his clean-scrubbed image as an invaluable manager to win a series of promotions. Eventually he became the Director of the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation in 1924. He never lost his conviction that a violent, left-wing conspiracy threatened the stability of the United States.

Beverly Gage, Author: The Red scare years remain really important to Hoover for the rest of his career. A lot of what he learns in those years he holds on to ideologically but also strategically as well. If you’re going to keep your files, if you’re going to go after people, you wanna kind of keep that quite close to the vest.

Narrator: All the while he was promoting the Bureau as a modern crime fighting organization, Hoover never stopped investigating people for their political ideas. He continued to add information to the secret files he created at the radical division, laying the groundwork for the agency’s espionage efforts in the decades to come.

Hoover speaking to camera: no case ever ends for the Federal Bureau of Investigation until it is solved and closed with the conviction of the guilty or the acquittal of the innocent.

Narrator: Hoover never was able to convict anyone for the Wall Street bombing. The Bureau’s last active investigation into the case was in 1944.

The Wall Street bombing remains unsolved.