Narrator: On a chilly August day in 1936 just outside Berlin, Germany, a team of American boys prepared to row the biggest race of their lives at the Olympic Games.

The competition that would become known as Adolf Hitler’s Games was nearly complete. The Nazi leader had regarded the Olympics as a chance to introduce the world to the glory of a new Germany and prove Aryan supremacy through athletic triumph. The host nation had won more medals than any other, and on this afternoon, with Hitler at the race course, German rowers earned gold medals in the first five races of the day, to the delight of the Fuhrer.

Now, in the final race, they were looking to continue their domination.

Timothy Egan, Author, The Worst Hard Time: The Americans walk into this thing, thinking they’re in a race. But what they actually are, are part of a global stage.

As tens of thousands of spectators filled the grandstand, and millions back in the United States tuned into their radios, the Americans entered the water.

With a key member of their team suffering from a severe lung infection and the worst lane assignment on the course, putting them directly in the face of an unrelenting wind, adversity was once again shadowing the nine boys who’d brought their racing shell across the world from what was still America’s frontier.

Timothy Egan, Author, The Worst Hard Time: These guys were nobodies. The odds of these blue-collar boys, living in the worst time in American history, becoming sports heroes, are just astronomical.

Narrator: On October 9th, 1933 in Seattle, at the old airplane hangar that served as the University of Washington’s shell house, several dozen boys showed up for crew practice.

The bulk of them would ultimately succumb to rowing’s cruel demands, leaving the team behind. A few of them, however, would not.

Timothy Egan, Author, The Worst Hard Time: These kids were very representative of the Pacific Northwest, which was raw, newly shaped. The city of Seattle was only about eighty years old. These boys were the sons of loggers, the sons of fishermen. They did odd jobs for a buck a day. They used their hands as claws and their backs as levers, you know. They were grunts.

Daniel James Brown, Author, The Boys in the Boat: This was the middle of the Depression and these guys were having a hard time putting a couple of meals a day in front of themselves.

Narrator: One member of the Washington crew, well acquainted with that hardship, was a 19-year-old named Joe Rantz.

Rantz had been born the second of two boys, in Spokane, a lumber town across the state from Seattle. When he was four years old, he watched his mother die of lung cancer.

Daniel James Brown, Author: He remembered the handkerchief with blood on it when she’d take it away from her mouth. He remembered being at her funeral. But he never really knew his mother.

Narrator: He was sent east to be with an aunt for a time and, eventually, returned to the care of his father Harry and stepmother Thula. Their life together was fraught with financial troubles and emotional tension from the outset.

Daniel James Brown: They found themselves living at this Gold & Ruby Mine out in Idaho. Thula took a dislike to Joe almost immediately. One day, Joe got in a spat with Thula’s child. Thula was just outraged and demanded that Joe leave the house. Joe’s father took him up to the schoolhouse and the teacher agreed to let Joe stay there if he would chop wood to keep the stove fed day and night. To feed himself he had to work at the camp kitchen. So he found himself basically living on his own for the first time when he was just ten years old.

Narrator: Joe lived in the schoolhouse for a few months before moving with his family to another town in Washington. There, the Rantzes’ troubles only deepened and Joe became a casualty of the desperation.

Daniel James Brown, Author, The Boys in the Boat: A day came when Joe came home from school and he found the family car with the whole family in it and all kinds of luggage in it. And he didn’t know what was going on and his father said, ‘We can’t make it here. We’re gonna leave, Joe but the thing is, you’re gonna have to stay behind. Thula doesn’t want you to come with us.’

Judy Willman, Daughter of Joe Rantz: He started to drive out the driveway and Harry and Mike, the little brothers, were looking out the back window of the car and he could just hear Harry screaming, ‘What about Joe? What about Joe?’

Timothy Egan, Author: It was emblematic of other kids during the Great Depression. You had the economic thing -- not knowing where your next meal is gonna come from -- and then you had the family dysfunction. The only place you can go, the place to call home, that was taken away from Joe Rantz. And it was somewhat typical because people felt like; ‘I just don’t have the means to, to give food to this child’. So he comes out of those two completely broken systems -- the two foundations of living basically.

Judy Willman, Daughter of Joe Rantz: But there was where he really had to make the decision of, ‘Am I a victim or am I a survivor?’ Because he had to pick up his life from there -- had to -- somehow.

Narrator: The teenager lived alone for two years. He hunted and fished for food and made money by selling stolen liquor and working as a logger. All the while, he remained in school.

Then his older brother invited him to come live in Seattle. For the first time, he could live something close to a normal life. He began competing in school sports. One day, he caught the eye of the University of Washington crew coach, Al Ulbrickson, who was looking for potential rowers to recruit.

Daniel James Brown, Author: Ulbrickson showed up at Roosevelt High School and he noticed this big, tall, blond kid on the gymnastics equipment. Joe had great upper body strength. He’d been cutting hay and digging ditches from the time he was fourteen on.

Judy Willman, Daughter of Joe Rantz: I’m not even sure before that that he really had his eye on college. He had somebody that wanted him. I think he saw an open door and he decided he would go through it.

Daniel James Brown, Author: There were no scholarships for rowing at the University of Washington in those days. As long as you were in good standing on the crew, they would find a part time job for you somewhere on the campus. And for somebody like Joe Rantz that made all the difference.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: There were multiple men on that team that were finding it hard to survive and had found it hard to survive up to the time that they had gotten to Washington.

Daniel James Brown, Author: Gordy Adam worked on a salmon boat to make money for college. Very hard working kid -- very tough.

Roger Morris would find himself working for his father on the weekends, time and again, moving families out of their homes, homes they had lost because of the Depression.

Stub McMillin was working at nights as a janitor. Stub was having a very hard time making ends meet.

Timothy Egan, Historian: Some of them got into rowing for the food. I mean they knew they were gonna get fed regular meals by the University of Washington, which seems laughable to a modern audience but it was a big deal back then.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: So these guys were hanging on by the skin of their teeth.

Narrator: By June of 1934, at the end of his first year on campus, Joe Rantz had emerged as one of the strongest rowers on the freshman crew. He joined his Washington Huskies teammates on a journey across the country to Poughkeepsie, New York, site of the national collegiate rowing championship. There, Rantz and his teammates would face crews from Cornell, Columbia, and Penn -- opponents with backgrounds very different than their own.

Timothy Egan, Author: You have the worst lot in life against privilege, and all of that happens when they go against the Ivy Leaguers. But then add to that the regional thing of, ‘Oh the Pacific Northwest. I suppose if I ever thought about it I wouldn’t care. But I don’t ever think about it because you’re off the map.’ That’s a real generator because it goes to that chip on their shoulder -- that insecurity that you do not respect us or even understand us.

Narrator: From coast to coast, in the 1930s, rowing was one of the nation’s most popular sports.

Radio Announcer (Archival): 60,000 spectators see the classic rowing field in the far west.

Narrator: Thousands of fans attended regattas where they cheered their favorites from beaches, docks, rooftops, ferries and even open observation trains that ran the length of race courses.

The biggest race of the ‘34 Poughkeepsie championship was the varsity competition -- won by the University of California -- the longtime west coast powerhouse. But the Washington freshmen were the revelation of the regatta, capturing their national collegiate title by five boat lengths over Syracuse.

Judy Willman, Daughter of Joe Rantz: It was almost like it was effortless. They came out of that sitting up instead of gasping. There was a huge amount of press and speculation of whether this was an Olympic team.

Narrator: The New York Times called the performance of the Washington crew ‘stunning’ and ‘serene.'

Daniel James Brown, Author: I think trust is the single-most important thing in rowing. You really do become part of something larger than yourself. Every time you take a stroke, you are counting on everybody else in the boat to be putting his whole weight -- full strength -- into that stroke. That is only gonna happen if every man in that boat trusts the others on a very fundamental level.

Narrator: The freshmen champions returned to the shell house as sophomores to train for the upcoming 1935 spring racing season.

Most observers thought they would be named to the top varsity boat -- the crew that would give Washington its best chance to get to its first-ever Olympics in Berlin the following year. But the idea that Joe Rantz and the sophomores were the boat to beat was deeply resented by upperclassmen.

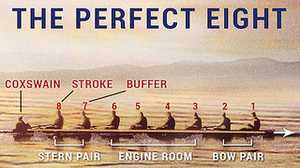

One of the more vocal dissenters was Bobby Moch. Just five feet seven and 119 pounds, Moch was a coxswain, tucked in the rear of the racing shell, where light weight was an advantage. A Coxswain commanded the pace and direction of the boat, and ensured the rowers in front of him were fully in concert.

A Phi Beta Kappa student, Moch had endured a childhood racked by asthma, in a logging town in southwestern Washington. He took his seat in the racing shell every day the same way he approached everything: set on defying anyone who doubted him.

Marilynn Moch, Daughter of Bobby Moch: He was on the basketball team (giggles). He constantly played sports. He was very competitive. He was very smart, but he did not see himself as smart. He saw himself as disciplined.

Daniel James Brown, Author: His strength in the boat was this sort of attitude that I’m in charge. And that’s exactly what Bob Moch was so good at. And Moch always had his chin up a little bit -- and just exactly what you want in a coxswain.

Newsreel Announcer (Archival): With the Olympic games in view, the University of Washington crew gets the jump on eastern oarsmen.

Narrator: Like every other upperclassman, for Bobby Moch, the central goal of the 1935 season was to find his way into the varsity boat, ahead of Joe Rantz and the sophomores.

Newsreel Announcer (Archival): While the ice-bound easterners work out in gymnasiums, the Huskies pile into their shells.

Narrator: There was no relief from the winter’s long daily practices, punishing workouts, and countless time trials.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: It’s painful. You’re talking about hours of work at a relatively high heart rate. You’re pushing the limits of your body every single day.

Narrator: It was all overseen by a coach, who just a decade earlier, had been a star Washington rower himself.

Al Ulbrickson had won two national championships as a Husky, but never got to an Olympics. As the team’s coach, he’d watched rival California win gold medals at the 1928 and ‘32 Games.

Bob Ernst, Rowing Coach: That’s huge motivation for a coach. If you’re a great athlete and you don’t make it to the Olympics and you don’t get a gold medal, then that, that’s a fire burning all the time.

Daniel James Brown, Author: Al Ulbrickson was a pretty hard man. He was not at all communicative. Sportswriters called him the 'Dour Dane.' He was very stern. So I don’t think any of the boys that rowed for him felt real warm and fuzzy about him.

Narrator: The taciturn coach appeared content to fuel months of battle between his rowers as the first race of the season approached. In the boathouse, confusion, tension, and hostilities between the sophomores and upperclassmen escalated.

Daniel James Brown, Author: Ulbrickson would sometimes just jerk boys out of boats without giving an explanation. Some of the kids had a hard time with that. Joe Rantz certainly did. It made him very uncertain about things.

Peter Mallory, Rowing Historian: Nobody challenged Ulbrickson. He put the line ups up on the chalkboard. He barely said anything in the launch. It was very toxic -- boats not talking to one another.

Marilynn Moch, Daughter of Bobby Moch: My dad liked to play mind games on the others, primarily coxswains, but also the guys that were rowing if he could think of a way to do it.

Michael Moch, Son of Bobby Moch: He wasn’t liked to start with at all. And these guys were in the way if they weren’t gonna pull their oar. And he was really pushy, you know. I mean, he -- this was gonna happen.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: There was this animosity that led to a bare-knuckle kind of environment. There would be almost vicious competition between the men.

Daniel James Brown, Author: There were shoving matches. Feelings got very hurt. Psychologically this was a hard game that these kids were involved in.

Narrator: Ulbrickson waited until after dinner the night before the first race of the 1935 season to finally announce his decision: he named Rantz and the sophomores the top varsity crew over Moch and the more experienced rowers on the team.

The next day, April 13th, the coach’s faith was rewarded when the sophomores edged out a victory at the annual Pacific Coast Regatta, a dual race against Cal.

But when training resumed, Ulbrickson still had questions about his top crew, testing them relentlessly in practice, and watching them grow sloppy and unpredictable.

Just before the national championship, Ulbrickson reversed himself. He elevated Bobby Moch’s crew to the top boat, and demoted the stunned sophomores.

Judy Willman, daughter of Joe Rantz: They had gotten themselves to the place where it was kinda easy to be demoralized. And they didn’t have the kind of confidence in each other that they had to have to be consistently competitive.

Radio Announcer (Archival): And there they go! Seven finely trained crews, churning the fog-shrouded waters of the upper Hudson, in the supreme rowing test of power, speed and coordination.

Narrator: On June 18th, 1935, a blustery day in Poughkeepsie, Bobby Moch took Washington out to an early lead. But Cal and the rest of the field soon caught up.

Radio Announcer (Archival): California leads Washington by a length, approaching the river bridge at the three-mile mark.

Narrator: Cal won its third straight national championship.

Radio Announcer (Archival): In a surging drive, the California Bears nose out the Cornell shell.

Narrator: ...positioning themselves as favorites to return to the Olympics, now just a year away.

The Huskies, meanwhile, returned to Seattle a worn-out, fragmented team. Ulbrickson had gambled, and lost. Now, after the upheaval between the sophomores and upperclassmen, they were all in danger of missing out on the Olympics.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: A good coach creates the framework for a team to trust each other. And so there was a breakdown of trust in the shell house.

Daniel James Brown, Author: George Pocock was so much more than a boat builder. He really in many ways was a sage. And Pocock taught generations of rowers at Washington to approach rowing as if it were a craft. He said, ‘When I build a shell I leave a piece of my heart in that shell. When you walk away from a race, I want you to walk away having left a piece of your heart in that race.’ He really believed that by rowing as well as you could you were lifting yourself up and making yourself better. And if you rowed well enough, he said, ‘you were approaching perfection. And if you approach perfection, you were approaching the divine.’

Narrator: Going into the 1936 rowing season, George Pocock had been a fixture at the University of Washington for more than two decades. He’d grown up in England building boats with his father at Eton, the prestigious secondary school on the Thames river, the birthplace of the sport of competitive rowing.

Within a few years of his arrival in America, Pocock set up shop building racing shells in the loft above the Washington boathouse. An accomplished oarsman as well, Pocock became a valued advisor to Washington coaches along the way, including Al Ulbrickson.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: There was a very, very strong connection there. George was a man of few words as well. I can imagine Al Ulbrickson and George Pocock in the launch and nothing being said the entire time they’re out there except for maybe two or three words. But those two or three words likely were very powerful and probably changed things along the way.

Narrator: With the Olympics just months away, Ulbrickson was determined to put his mistakes of the previous year behind him. He made clear to his team that the upcoming season would be their most grueling yet, and added a sixth day of training to every week. Every seat in the varsity boat was up for grabs. It was every man for himself.

There was one rower whom Ulbrickson approached differently, whose raw potential he’d first spotted in a high school gymnasium, but who’d grown too erratic to be depended upon -- Joe Rantz.

Daniel James Brown, Author: Ulbrickson takes him out of the boat. The boat slows down. Ulbrickson puts him back in the boat, the boat goes faster but then it goes slower the next day. And he can’t figure out why Joe Rantz is so uneven. So he finally asks George Pocock.

Judy Willman, Daughter of Joe Rantz: George Pocock was almost like a father-figure. He was somebody who saw dad’s potential. Dad was sinking from boat to boat. As somebody who had sort-of been a throw away kind of person, he found himself being thrown away again.

Daniel James Brown, Author: He developed an attitude that he had to do everything his own way. And that worked for him living out in the woods. But that was really a problem for him when it came to crew. Pocock really begins to teach him that if he wants to be great he needs to understand that he’s part of something bigger than himself. He needs to begin to trust.

Peter Mallory, Rowing Historian: Going into ’36, this was it. This was when he had to do it. Ulbrickson was well aware that he had to take advantage of the enormous talent from the ’34 freshmen boat. And he had to take advantage of the enormous talent of Don Hume.

Narrator: After just one season on the team, Don Hume was being talked about as perhaps the best Washington stroke-oar -- the rower charged with keeping the rhythm of the boat -- since Al Ulbrickson himself.

The sophomore was not physically imposing, but he’d led his freshman boat to resounding victories the prior season.

Daniel James Brown, Author: He actually worked in a pulp mill as a kid. And there was an unfortunate consequence of that. Fumes in the mill damaged his lungs. So it made him very susceptible to respiratory illnesses. He had a very hard time shaking them off.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: Al Ulbrickson would have preferred to have a two-hundred-pound guy in there who could pull twice as hard as Don Hume. But Don Hume was special.

Bob Ernst, Rowing Coach: He had a natural feel for the rhythm of the water and how fast the boat would move. They don’t have to be the most powerful person and they don’t have to be the biggest person, but they gotta have a sense of what’s moving the boat. Don Hume would just do his job and all the guys super respected him for that.

Narrator: By mid-March, Hume was a regular in the lineup that Ulbrickson envisioned for his varsity boat. In his daily logbook, he added another name he hadn't written for some time. Over the next several practices, the boat got faster.

Daniel James Brown, Author: So Pocock’s advice would work for Joe in this boat. That was a bunch of guys that Joe could trust. And Ulbrickson knew at that point he had the boat that he wanted to try to take to Berlin.

Narrator: The varsity crew was named four months before the Olympics.

Bobby Moch was the coxswain, Don Hume was the stroke oar, with Joe Rantz and Shorty Hunt seated behind him. The powerful “Stub” McMillin in the middle, then Johnny White and Gordy Adam, Chuck Day, and Roger Morris in the bow.

After so many months of second-guessing, and bruised egos, the former boathouse adversaries comprised a powerful Washington crew.

In their first race together, the Pacific Coast Regatta in April, they accelerated away from Cal and annihilated the course record by 37 seconds.

‘All were merged into one smoothly working machine,’ the Seattle Post-Intelligencer noted. ‘They were, in fact, a poem of motion, a symphony of swinging blades.’

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: Swing comes when you really have that harmony. Synchronicity -- eight hearts beating as one as George Pocock would say. It’s elusive. It doesn’t happen every day.

Bob Ernst, Rowing Coach: Swing -- it’s the sweet spot. It’s a perfect connection. And the best teams dream about having it in the big races because then they know they can’t be touched.

Narrator: In June, the national championship in Poughkeepsie loomed. A few days before their race, Ulbrickson gave them the day off, and the boys from Seattle decided they would visit one of the local residents.

Daniel James Brown, Author: They know that President Roosevelt lives at Hyde Park just up the river. And they get it in their heads that they’re gonna go visit the President. They find a gardener who points it out to them. They walk up, and knock on the door and one of the Roosevelt sons comes to the door. And he is himself a rower so he invites them in. And for the next hour or so they talk about rowing sitting in President Roosevelt’s parlor. One of the guys sits actually in the chair that Roosevelt sometimes delivers his fireside chats from. Johnny White writes a little note in his diary that night. “They sure have a swell place.”

Radio Announcer (Archival): The historic Poughkeepsie regatta draws seven varsity shells to the starting line and a crowd of spectators to the sideline.

Narrator: The national championship was June 22nd. Washington’s strategy was to exercise patience in the four-mile race.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: Don Hume and Joe Rantz and all of those guys -- Stub McMillin -- they all knew the plan. They would row the first two miles of that race in cruise control. And then they would start to pick it up.

Daniel James Brown, Author: As the boats are in their third mile, Ulbrickson can’t quite believe what he’s seeing because Bobby Moch has got the boat four lengths behind the leaders.

Eric Cohen: He’s riding the train with George Pocock and he’s going, 'Come on! Come on! You guys gotta go now!'

Daniel James Brown, Author: Moch continues to hold the boat back and then, at the last possible moment, he finally leans in and tells Don Hume to pick the pace up.

Peter Mallory, Rowing Historian: Bobby Moch had faith in his team. He just stayed cool and calm and then just mowed them down.

Radio Announcer (Archival): The Huskies of Washington proceed to sweep the river, surging to victory to become the ace candidate for the Olympics.

Narrator: With reporters afterwards, Ulbrickson praised his coxswain. ‘I guess that little runt knew what he was doing.’

Two weeks later, Princeton, New Jersey was the site of the Olympic Trials. Despite everything they’d already achieved, the boys had to win one more time to become the first Washington crew to represent the United States in an Olympics.

The strategy, once again, was to race from behind.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: The Olympic trials for Washington was probably one of the best races they ever rowed. And people were rightly intimidated by the way they rowed. You’re sitting there going, ‘Oh, oh no. Washington is three lengths back from us but they’re gonna come eat us alive. You know. We gotta hold on. We gotta hold on. We gotta -- oh no, here they come.’

Peter Mallory, Rowing Historian: And they waited a long time. It was four, five hundred meters from the end and Penn still had three quarters of a length and then Moch said, 'Let’s go.' And bam! They just exploded and went right through them.

Narrator: Ulbrickson spoke to the national press after the race. ‘Why they won cannot be attributed to individuals,’ he said. He got to the heart of the matter when he noted, ‘Every man in the boat had absolute confidence in every one of his mates.’

Henry Penn Burke, Olympic Rowing Committee (Archival): The crew of the Washington University, I want to congratulate you on winning the championship of American eight-oared crews.

Narrator: On the morning of July 15th, two and a half weeks before the start of the Olympics, the boys from Washington who had previously only been on lakes and rivers, began a journey across the Atlantic Ocean. The S.S. Manhattan luxury liner was a 668-foot ship that would transport 334 members of the U.S. Olympic team to Germany -- and also -- a sixty-two foot Pocock racing shell.

Timothy Egan, Author: When they get on a boat to cross the Atlantic, they’re all pinchin’ themselves. Their world had gone very quickly from the sawmill, the edge of the forest to the biggest stage of all.

Narrator: Over the ten-day crossing, Don Hume, always prone to respiratory infections, began struggling with a deep chest cold that persisted as the ship took them through the English Channel to Germany.

Bob Ernst, Rowing Coach: This was like going to another planet. These are guys that if they wanna know where Germany is they’re looking at a cardboard globe.

Daniel James Brown, Author: They actually saw a very clean, well-scrubbed city, very carefully laid out. There were swastikas hanging from every street corner. There were banners everywhere. But swastikas didn’t yet mean anything to Americans.

Narrator: The Opening Ceremony was held on August 1st at the newly built sports stadium. The hosts’ objective was not simply to welcome the world to Berlin, but to put on a show of national unity and pride unlike any the world had ever seen. To Adolf Hitler, the Games were the ultimate propaganda tool.

David Clay Large, Historian: He was a very effective propagandist and he was going to use the Olympics as his great show. He was going to bring out onto the world this new healed Germany, this reunified Germany, a stronger Germany, but also, he insisted, a peaceful Germany. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, he was planning for war.

Narrator: Hitler expected the German teams would dominate the Games. The rowing team that the host nation brought to the narrow lake, Langer-See, was no exception.

Peter Mallory, Rowing Historian: The German team was extremely dominant. Their government made it a national priority that their sports teams should succeed. They had clubs all over the country that were well coached, well funded.

David Clay Large, Historian: They’re given uninterrupted training. If they have jobs they quit the jobs. And they are sponsored by the government.

Timothy Egan, Rowing Historian: The University of Washington, the Americans, come in as poor athletes from an unknown part of the world. Their ethic is because these guys worked on farms and crappy jobs. So there’s sort of a purity versus this artifice.

Daniel James Brown, Author: The boys went out and just sort of explored the streets. And they quickly discovered that whenever Germans walked up to them they would extend their hands, give the Nazi salute and say, ‘Heil Hitler.’ And so the boys didn’t quite know what to do about that so they took to walking up to Germans, extending their hands and saying, ‘Well, Heil Roosevelt!’

Narrator: Eight days before the gold medal race, Ulbrickson grounded his team. They were rowing poorly in workouts and the chest cold Don Hume had contracted on the trip over had gotten worse, not better.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: Don Hume went from a hundred and seventy pounds to about a hundred and fifty-eight pounds over that period of time. It was an extensive amount of weight loss.

Daniel James Brown, Author: He was very sick. He had a high fever. He had been kept in bed for several days and going into the day of the medal race, Ulbrickson didn’t think that he could row.

Narrator: On the morning of the final race, with Hume’s fever rising once again, Ulbrickson announced that he was going to remove his stroke from the boat, and replace him with an alternate. When he told the team, they refused to leave Hume behind.

Bob Ernst, Rowing Coach: The guys just absolutely could not see themselves racing without Don Hume in the stroke seat. He’s the guy who’s leading the dance step. And if it was a little bit shaky, we’ll make up for that.

Daniel James Brown, Author: They put it to him almost as an ultimatum and that was a very unusual thing. Ulbrickson thought about it for a bit and he decided this was a case where he had to trust the instincts of the boys. He was gonna put Don Hume in the boat.

Judy Willman, Daughter of Joe Rantz: They were going to win the race for each other. They had each other’s backs.

Narrator: August 14th, race day, was chilly and rainy.

In the men’s eights, the marquee event, the Americans faced a full slate of intimidating opponents.

Peter Mallory, Rowing Historian: George Pocock, being a Brit himself, was rightly concerned about the British entry. They were full of Oxford and Cambridge boat race veterans. So it was an all-star crew. They’d won in ’08, ’12. They had been second in ’20. They were always on the premises.

The Italians were a group of longshoremen from Livorno. They had been together as a team for more than ten years. They were big, strong guys. They were literally the most experienced crew in the field.

The German team won the first five races. They were the class of the Olympics.

David Clay Large, Historian: The Germans wanted desperately to win the heavyweight eights -- very important because that was the most prestigious of all the rowing contests. They knew the course like the backs of their hands. So they had a huge advantage in that regard.

Narrator: The Germans had another distinct advantage in the race: the best lane assignment -- even if it appeared to have been dubiously determined.

Daniel James Brown, Author: Although the Americans had the fastest qualifying time, and the Brits had turned in the second fastest qualifying time, they were mysteriously assigned lanes five and six out in the windiest part of the racecourse. Italy and Germany had turned in relatively slow qualifying times; they were assigned lanes one and two, protected from the wind.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: How they would end up with the best lanes and the teams that had won their heats would end up in the worst lanes. There’s nothing to explain that.

Narrator: At a quarter past six in the evening in Germany, it was still morning back in Washington. As the state and much of the nation listened in on their radios, the Americans paddled to the start line.

Radio Announcer (Archival): It’s a very interesting sight to be here and describe this to you. The Washington crew is probably the slowest starting crew in the world -- it gives everybody heart failure.

Daniel James Brown, Author: The crowd is already chanting, ‘Deutschland, Deutschland, Deutschland.’ They don’t actually hear the call of the start of the race.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: The Washington crew had a horrible start. Horrible. They were thrashing.

Radio Announcer (Archival): I can see that Italy is leading, Germany is second, Switzerland’s third.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: They were a quarter way through the race and they are behind the field. They were facing the wind and the chop.

Peter Mallory, Rowing Historian: Suddenly, Don Hume seemed to go into a trance.

Radio Announcer (Archival): The American crew appears to be fairly well in the rear.

Daniel James Brown, Author: Don Hume hasn’t been responding to Bobby Moch’s calls to him to pick up the rate.

Judy Willman, Daughter of Joe Rantz: Bobby Moch knew that if something didn’t change, everything was lost.

Radio Announcer (Archival): And the United States dragging along. Not in the first three.

Daniel James Brown, Author: Suddenly Don Hume pops his head up and starts rowing beautifully. And the boat explodes forward.

Radio Announcer (Archival): The United States is beginning to pick up quite rapidly now that good ol’ Washington rush.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: Within a thousand meters, they had started to move back on the field.

Radio Announcer (Archival): Washington crew is driving hard on the outside of the course.

Peter Mallory, Rowing Historian: There were people screaming down on them. It must have been absolutely deafening.

Judy Willman, Dughter of Joe Rantz: Nobody could hear him. Even Don Hume couldn’t hear him fifteen inches in front of him with a megaphone. He did the only thing he could, which was start whackin’ on the side of the shell.

Peter Mallory: He could go puh-puh-puh-puh.

Radio Announcer (Archival): There is not one length’s difference between the first five crews!

Bob Ernst, Rowing Coach: They had to fight and claw and drag that boat.

Radio Announcer (Archival): The United States is in front with 50 meters to go!

Bob Ernst, Rowing Coach: It was a total gut check.

Radio Announcer: 40 meters to go...and they have half a boat length on Italy! 20 meters to go! 10 meters to go and the United States wins! With Italy second and Germany third, Great Britain fourth and Hungary fifth.

And Don Hume, the very light stroke on the American crew, who has lost something like twelve or fifteen pounds, stroked that great crew from the Northwest to the outstanding victory of the Olympic games.

Bob Ernst, Rowing Coach: It would have been really, really easy to lose. But I’ll tell you what, they were kids that were tough. They were used to working in tough conditions and they were used to paying a lot physically to accomplish a goal.

Daniel James Brown: Al Ulbrickson was watching from a balcony nearby with George Pocock and he fought his way through the crowd trying to get to the boys to congratulate them.

Narrator: A few moments later, Ulbrickson told a reporter that his boys were 'the finest I ever saw seated in a shell. And I’ve seen some corking boatloads.'

Daniel James Brown, Author: Mostly, they were very proud of not having let one another down. I think for Joe Rantz winning that gold medal, I think after all he’d been through, he knew he was valuable and he wasn’t the disposable boy he had once been.

Every one of them also had a measure of humility. And that humility was the gateway through which they were able to approach one another and start building the bonds of trust that really made them into the great crew that they became.

Eric Cohen, Rowing Historian: There is this element of redemption but there’s also this element of achieving a goal through trust and brotherhood.

Timothy Egan, Rowing Historian: They were considered rubes from the far west taking on the elite. Reaching in, finding something. The coming together from those disparate backgrounds -- hunger for some dignity in a world that wasn’t giving these boys dignity. I love the fact that they spoil the script.