Narrator: September 2, 1944, was what Navy pilots called CAVU — ceiling and visibility unlimited. It would be Ensign George H. W. Bush's 50th mission in his three-man Avenger bomber. He was commissioned in 1943 at age 19, the youngest pilot in the U.S. Navy. Bush had seen action in June over the Mariana Islands in one of the biggest air battles of the Pacific War. The target September 2nd was a Japanese radio tower on the tiny island of Chichi Jima. Bush dove into black puffs of anti-aircraft fire. "Suddenly, I felt the plane jolt," he remembered, "and the smoke started pouring in." He finished his bombing run, banked out to sea so the crew could get out, and then bailed out himself.

George H. W. Bush: Looked up and the parachute had been ripped up. Landed in the water. Swam over, got into my little life raft.

Narrator: The submarine U.S.S. Finback, on patrol for downed pilots, rescued him.

George H. W. Bush: I remember seeing that submarine surface. And I remember pulling along side and I remember a bunch of bearded guys standing there.

Narrator: For the next month, George Bush joined the Finback's crew. Aboard he agonized about the fate of his gunner Ted White and radioman John Delaney. One went down with the plane. The other's chute never opened. "It still plagues me if I gave those guys enough time to get out," the former flyboy said with quiet emotion almost 60 years later. "I think about those guys all the time."

Timothy Naftali, biographer: He was an emotive, an emotional leader, much more emotional than people thought. He cried quite readily. One thing that made George Bush a less appealing candidate was that he refused to show his emotions. That's not what a man did -- a man of his generation and of his upbringing. And so the public saw a slightly awkward man who didn't seem quite ready to share his true self with them. When you got to know him, the human side, the emotional side was there. It came out.

Narrator: "I'll never forget the beauty of the Pacific," Bush would write about the watches he stood at night. He had time to think about "how much family meant to me."

Narrator: George Herbert Walker Bush grew up in Greenwich, Connecticut in a family that came from Ohio and became one of New England's prominent families. His grandfather, Samuel Bush, made his fortune in railroads in Columbus. His father, Prescott, went to Yale and remained in the East. Prescott Bush was a partner in Brown Brothers Harriman, the most prestigious investment bank on Wall Street at a time when the influence of the WASP establishment in America, the white Anglo Saxon Protestants, was near its peak. Averell Harriman, Prescott's colleague and the firm's founding partner, was an aide to President Franklin Roosevelt in World War II. He then became U.S. ambassador in Moscow. His partner Robert Lovett was Assistant Secretary of War. After the war they were among a group known as the "Wise Men" who helped President Truman fashion the policy of containing the Soviet Union.

Richard Norton Smith, presidential historian: Prescott Bush was very much at home with the wise men, the essentially bipartisan, consensus-seeking, post-World War II statesmen. If you think of people like Robert Lovett, they didn't run for office, they exercised enormous power and influence from appointed positions.

Evan Thomas, co-author, The Wise Men: Even when Bush was a schoolboy in the 1930's at a time when America was isolationist, these men, these Wall Street financiers, were acutely conscious that America had to stay involved in the world, partly for financial reasons. I mean, Brown Brothers Harriman did business all around the world. They did business in France, in Germany, and in England. But also because of this American tradition of spreading democracy and standing up for democracy and standing up for, as they saw it, for right against wrong.

Narrator: George Bush was raised in this milieu -- people of wealth who devoted themselves to government service. His father, who later became a Senator, was the moderator of the Greenwich town meeting when George was a boy. He was George's model for public service.

John Robert Greene, presidential historian: Prescott Bush wanted his children to understand was that there was a world beyond the boundaries of Greenwich, and that they were expected to give something back to that world, whether it be through business, whether it be through public service, or whether it be through military service.

Narrator: Young George also bore the strong influence of his mother, Dorothy Walker Bush.

Doro Bush Koch, daughter: It was my grandmother who taught my Dad the basic lessons in life that he still adheres to. One time my dad was playing soccer in elementary school, and he came in and he was thrilled with himself because he'd scored three goals, and he said, "Mom, I've scored three goals." And he said, "Mom, I've scored three goals." And she said, "Well, that's nice, George, but how did the team do? He always heard her voice in his head, saying, "Don't brag about yourself." And that's hard to do when you're running for President of the United States.

Narrator: The Finback, Bush would write, "moved like a porpoise, water lapping over its bow, the sea changing colors, first jet black, then sparkling white. It reminded me of home and our family vacations in Maine." Bush was the fourth generation of his mother's family to summer at Walker's Point in Kennebunkport. It would become his spiritual home. George bore the name of his grandfather, George Herbert Walker, for whom the Walker's Cup, an international golf trophy, was named. His competitive spirit came from the Walkers.

Doro Bush Koch, daughter: My grandmother was a champion tennis player. She would play tennis until her feet were blistered and raw. She loved competition. She was a great golfer. She was a great baseball player. One time she hit a home run, rounded the bases, and then went on to the hospital to give birth to my father's oldest brother, Prescott.

Narrator: George Bush was captain of his baseball team at Andover, a prestigious prep school in Massachusetts. In fielding drills he would charge the plate from first base, "right down the baseline, streaking in," a biographer would write, "laughing with the pure joy of contest. That's why he was the one for captain. It was the glint of Walker steel his teammates saw. They wanted their team to be like that." At Andover Bush listened to radio broadcasts on the history of aviation in America.

ANNC radio (archival): Wings Over America... Welcome to Yale Unit Base #1, ladies and gentlemen...

Narrator: A group of wealthy aristocratic Yale students, including Robert Lovett, his father's business partner, turned their college "aero" club into the First Yale Unit. The "millionaire's unit," as the press dubbed it, became the nucleus of the navy air corps and an inspiration for George to become a naval aviator.

ANNC radio (archival): Our standard long-range bombardment airplane is known in the Air Corps as the B-17, the Boeing Flying Fortress.

Narrator: "Today our world is presented with the clearest issue between right and wrong which has ever been presented to it," Andover's commencement speaker warned on June 14, 1940 shortly after Hitler launched his blitzkrieg. The speaker was Henry L. Stimson, a Republican, a Wall Street lawyer, the very embodiment of the East coast establishment. Two days later President Franklin Roosevelt, a Democrat, named him Secretary of War.

Evan Thomas, co-author, The Wise Men: When Bush was an impressionable schoolboy, a 16-year-old schoolboy, he heard Henry Stimson give a speech about the coming threat from Nazism, from fascism, that it was the duty of the country to stand up to fascism. This is 1940. This is early in the game. A lot of Americans are still isolationists. But Stimson's telling these schoolboys, "Look, it's up to you, to you young leaders, future leaders of America, to stand up to evil and fight back."

Narrator: These were words the 16-year-old sophomore never forgot. Stimson, whom Bush regarded as "a towering world figure", returned to Andover two years later and urged the graduating class to go to college before joining the service. Bush rejected both Stimson's advice and his father's. Later that day, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy. It was June 12, 1942, his 18th birthday.

Barbara Bush, wife: His father took him to Penn Station, and George said his father put his arms around him and had tears in his eyes when he said good-bye.

Narrator: That was, Bush recalled, the first time he saw his father cry. From the Finback, Bush wrote his girl back home, "I hope my own children never have to fight a war." Friends disappearing. Lives being extinguished. It's just not right." Barbara Pierce grew up in Rye, New York. Her father, who became the publisher of McCall's magazine, commuted to New York on the same train as Prescott Bush. When Barbara was 16 she met George, age 17, at a Christmas dance in Greenwich.

Barbara Bush, wife: Well, he was the handsomest living human I ever saw, and maybe the nicest, most relaxed. They played a waltz and he said, "I can't waltz." So we sat down and talked, and that was sort of it. But I fell in love at first sight, practically.

Narrator: George's mother invited Barbara to Kennebunkport when he was on leave in August 1943.

Barbara Bush, wife: His whole family was up here. And we were never left alone. Had four uncles and four young brides, and a grandmother and grandfather and his mother and father. So we had to walk around outside. And we sort of got engaged secretly. We were way too young to be engaged.

Narrator: Barbara waited for two years while George Bush flew 58 combat missions, logged 1,208 hours of flying time and made 126 carrier landings. On January 6, 1945, Barbara Pierce married, she would come to say, "the first man I ever kissed."

Narrator: After the war, Bush followed his father and his brother Prescott and entered Yale. Two and one-half years later, he had a degree in economics, Phi Beta Kappa -- and a son. George W. was born in New Haven in 1946. Like his father, Bush was tapped for Skull and Bones, Yale's most elite secret society. Henry Stimson, now retired as Secretary of War, presided over his initiation. Despite his admiration for his father and for Stimson, Bush did not follow them into the world of finance. All three of his brothers did.

Barbara Bush, wife: He told me, "I want to work with something I can touch. I don't want to work on Wall Street with money, and I don't want to go into a sort of family business. I really want to work with something I can touch."

Ajax commercial (archival): Use Ajax, boom boom, the foaming cleanser.

Peter Roussel, press aide, 1970-74: One of his very first job interviews, maybe his first, was at Procter & Gamble. He had an interview. And he got rejected, got turned down for the job. And I asked him one day, I said, "Have you ever thought about that much, how your life might have been totally different? And he said, "I'd probably been a lousy soap salesman." Actually he said, "It helped me, because I thought: You know, I'm going to show these people that I do have the right stuff. I'm going to go out and make it somewhere else."

Narrator: Lured by the romance of a post-war oil boom, the Bushes headed to West Texas.

John Robert Greene, presidential historian: He wants an adventure. He wants a challenge. And there was nothing more challenging than Wildcatting oil. This is the greatest adventure you can have on the continent -- on the United States continent after World War II. It's the closest thing to uncharted territory that you can have.

Narrator: George Bush started in the oil business in Odessa in 1948 painting spare pumps for $375 a month. He was on a management track, but within two years, with two children to support, he struck out on his own as a wildcatter.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: George got investments from his uncle Herbie, his father, and people like Eugene Meyer of the Washington Post. It was not only a way to make a fortune. It was a way for him to stake out on his own.

Narrator: Bush's company Zapata Petroleum hit it big in 1954. Five years later George and Barbara moved to Houston, the headquarters of Zapata Offshore. George was prospering as its president, but there was a void in their lives. They hoped that Barbara, who was pregnant, could fill it. Their second child, Robin, had been born in 1949. She was diagnosed with leukemia when she was three. Their doctor advised them to let her die at home. Instead, they took her to New York's Sloan Kettering Hospital. Yale classmate Lud Ashley visited daily.

Lud Ashley, classmate: George was running the household back in Texas, flying up weekends -- flying from Texas when it used to take eight or nine hours to fly to New York. Barb was there all the time. Almost 24 hours a day. In all my years I've seen such a strength of character as she showed during that desperately difficult time.

Doro Bush Koch, daughter: My Dad told me that he had trouble looking into her eyes and comforting her and doing the things he wanted to do. My mom was the one who was able to hold her hand and love her and comfort her. But then later on, when my mom fell apart after Robin died, it was my dad who looked in her eyes and held her hand, and gave her the strength to go on.

Narrator: Robin died on October 12, 1953, two months before her fourth birthday.

John Robert Greene, presidential historian: I believe that the death of Robin sobered George Bush and turned him into an adult that could be an empathetic politician, that could be an individual who could strike on civil rights and disabilities for Americans. I really think that it was that important.

Narrator: In the late 1950s, after the birth of Jeb in 1953, Neil in 1955 and Marvin in 1956, Bush wrote a letter to his mother: "There is about our house a need. We need some starched crisp frocks to go with all our torn-kneed blue jeans and helmets. We need some soft blond hair to offset those crew cuts. We need a dollhouse to stand firm against our forts and rackets and thousand baseball cards. We need someone to cry when I get mad -- not argue. We need a little one who can kiss without leaving egg or jam or gum. We need a girl."

Jeb Bush, son: I read that letter in my mom's book, and actually listened to it on tape. I was driving home on I-95, the traffic was going crazy, and I started crying uncontrollably. I had to stop in the middle of this interstate. I called my mother up to tell her how much I loved her and how much I loved my dad, and she of course -- her immediate response was, "You didn't read the book. You had to wait for the tape to come out." She gave me grief for that. But it was pretty typical of my dad to write those kinds of letters.

Doro Bush Koch, daughter: I just learned this story a few years ago, on my birthday, when my mom wished me a happy birthday and she told me that she remembered the day I was born, that Dad came to the nursery and pressed his face against the glass and sobbed.

Narrator: The success of Zapata Petroleum, Bush recalled, "gave me the financial base to risk going into public life." George's father, Prescott Bush, was a Republican senator from Connecticut. "I knew what motivated him, "George would write, "He'd made his mark in the business world. Now he felt he had a debt to pay."

Richard Norton Smith, presidential historian: Noblesse oblige has become a pejorative, but it wasn't always a pejorative. The notion of an American meritocracy, which is what the wise men represent, that's the old Eastern establishment. It isn't simply the nexus of power. It's the obligation to use that power in a responsible way, not for one's own benefit, but for what you sincerely believe to be the benefit of your fellow countrymen. Prescott Bush represented that establishment. His son had one foot in that establishment.

Narrator: During his ten years in the Senate, Prescott Bush was a moderate, or Eisenhower Republican. He was pragmatic and non-ideological, believed in balanced budgets and was pro-business. He was also pro-civil rights and a social liberal. Prescott had joined the Senate when he was 57. His wife said if he had run earlier, he would have been President. His son would not make that mistake. George decided to enter politics when he was 38. He faced an obstacle his father never had. The Republican Party in Texas hardly existed.

Peter Roussel, press aide, 1970-74: You could probably have held a precinct meeting in a phone booth then. That's how many Republicans were around.

James A. Baker, III, friend: My first wife was from Ohio. And that's a big Republican state. And when we moved back here from Austin after law school, she conducted the precinct convention in my living room, and one guy showed up. I served him drinks. I mean that's how limited the Republican participation was in Texas back in those days.

Narrator: Houston's few Republicans, Bush among them, were members of the establishment -- country club Republicans. Their party was about to change. The radical anti-communist John Birch Society tried to take it over. Birchers thought President Eisenhower was a communist -- he had appointed a Chief Justice who turned out to be a liberal.

Richard Viguerie, conservative activist: The country club Republicans, the establishment, what I call the big-government Republicans even in those days, they would be uncomfortable with true believers. People who really had deeply held philosophical, ideological beliefs makes establishment Republicans uncomfortable, quite frankly.

Narrator: In 1962 Bush was asked to run for chairman of the Harris County Republican Party to keep the Birchers out. It was his first political campaign. "I'm not voting for 'nother country club asshole," one of the right-wingers said. "Y'can jus' fergit it."

Marjorie Arsht, political supporter: George stepped right into the middle of it. And you know, I have loved George Bush for 40 years, but he does have one failing. He does not recognize an enemy.

Barbara Bush, wife: My dad at that time was president of McCall Corporation, and they printed and published Red Book, Blue Book, and McCall's. And they sent out -- one meeting we went to, the lights went out, someone was speaking, and papers were all passed down. When the lights went on, it said, "Mrs. Bush's father is a Communist. He prints the Red Book. Crazy. They said things like, " George is a Rockefeller plant," or, you know, "He grew up in the east. He's not one of us." "He's liberal."

Narrator: After he won his race, Bush wanted to give some Birchers positions in the party. "George, you don't know these people," a colleague warned. "They mean to kill you."

Victor Gold, friend: George Bush's instinct politically is to bring people together, to be a uniter. And so he didn't come in in a confrontational style, slam the door and throw all the Birchers out. His idea was, "Let's get the Birchers and have some common meeting ground with them, because if we want to beat Democrats, if we want to we need those people.

Narrator: Bush saw another opportunity to expand the party after groundbreaking legislation on civil rights was introduced in June 1963 by President John Kennedy.

John F. Kennedy (archival): Next week I shall ask the Congress of the United States to act, to make a commitment it has not fully made in this century to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law.

Narrator: Civil rights was about to tear the country, and the Democratic Party, apart. Many Democrats in the South were committed to segregation. As they saw their party support integration, they began to seek refuge in the Republican Party.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: Poor white workers in Texas and elsewhere felt there was a threat, of all these hordes of blacks becoming unleashed and competing with them for status and jobs. And so you have the mass turnover to Republican Party in the South, state after state.

Narrator: Among the disgruntled Democrats in Houston were dockworkers who felt their jobs would be threatened by African American workers. They sought out the new Republican chairman, George Bush.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: They were segregationists. They were trying to maintain conservative control over Harris County.

Marjorie Arsht, political supporter: And I didn't like them being Republicans, because I thought it gave our party a bad name. George didn't see a thing wrong with it. He was eager to expand the Republican Party, and he felt the only way to expand it was to attract Democrats.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: Bush thought they were crazy. But he thought that politically he had to accommodate himself to them.

Marjorie Arsht, political supporter: I didn't think they were crazy. I thought they were very dangerous. They wanted to convince the world that the Republican Party was now going to be a segregationist extension of the old Democrats. The Democrats called me up and congratulated me on getting those bastards out of their party.

Timothy Naftali, biographer: Throughout his political career, George Bush often seemed to lack a sense of principle. As a candidate, he often sacrificed principle for political gain.

Narrator: If he did something unsavory to advance his career and his party, the result would be momentous. The people Bush accommodated in 1963 would support Senator Barry Goldwater for President in 1964 and thereafter Ronald Reagan.

Richard Viguerie, conservative activist: And they become the nucleus of the new Republican Party, not only in Texas but across the country. And this was the beginning of the conservative movement, and to this day it serves as the base of the Republican Party.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: You could say that George Herbert Walker Bush was in on the creation, with this organization of Harris County Republicans, because that's where it began. Think of what that started.

Narrator: The party that George Bush created in Houston in 1963 grew into the party which he would lead -- and struggle with -- as president.

Barry Goldwater (archival): Those who do not care for our cause we don't expert to enter our ranks in any case.

Narrator: The champion of Americans who had flocked to the Sun Belt in the 1950s, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona led a sagebrush insurgency in 1964 against the Eastern establishment. He ran against big government, the New Deal, labor unions, and liberal or "Rockefeller" Republicans. Everything Prescott Bush represented, Goldwater saw as a threat to individual freedom.

Barry Goldwater (archival): I would remind you that extremism in defense of liberty is no vice.

Narrator: Prescott Bush tried to keep Goldwater off the ticket. George Bush ran for U.S. Senate, embraced Goldwater, and begged his father to keep quiet. After winning the first Republican primary in Texas history, Bush tried to unseat liberal Democratic Senator Ralph Yarborough. It was a bold move for someone who had only been a county party chairman.

George H. W. Bush (archival): Ralph Yarborough is the darling of the AFL-CIO bosses, and the committee on political education... I'd like my children to be able to pray in school if they want to. And I'd like that right to be a part of our constitution.

Campaign film narrator: Young George, the oldest Bush boy, is a college freshman. He spent his entire summer working at Bush headquarters, assembling campaign materials, answering phones and sweeping up too... We think George Bush is quite a man. A real American. A real Republican. A responsible conservative.

Narrator: Bush ran to the right. He denounced the United Nations, and pledged to vote against Kennedy on civil rights. Like Barry Goldwater, he argued federal enforcement of civil rights was a violation of states' rights.

Richard Viguerie, conservative activist: George Bush was anxious to launch his political career. And there was a fervor in the Republican Party for conservative principles in those days, and that was not his ideology but he felt that in order to get elected, I will go along, I won't try to convert people to my belief, I will flow with them.

Narrator: On November 22, 1963, a Houston Chronicle poll showed Goldwater leading President John Kennedy by 50,000 votes. Kennedy came to Dallas to gain support and to heal a rift between liberal and conservative Democrats in Texas. Kennedy's assassination that day completely changed the political landscape.

Shirley Green, Texas Republican: After the assassination, it was awfully uphill. Not that anybody gave up, I must say, starting with him. It was a real, real vigorous contest, because he inspired so many new people to come to the Republican side.

Narrator: Although Bush got 200,000 more votes in the state than Barry Goldwater, more than any Republican ever had, Texans voted the ticket led by their native son, the new President, Lyndon Johnson. Bush was trounced. He was also haunted by some of the far right positions he had taken, especially his pledge to vote against the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Marjorie Arsht, political supporter: And George Bush wrote me a letter saying that he was so troubled about this vote, because he didn't want his children or anyone to consider that he was voting against integration.

Narrator: Two years later, George Bush ran for Congress from a Houston district more moderate than Texas as a whole. He was elected handily, the first Republican Congressman from Houston since Reconstruction. One issue he faced was about to explode. African Americans took to the streets in 1967 demanding that the civil rights movement include fair housing.

Lyndon Johnson (archival): I am asking Congress to bar discrimination in housing and to secure very basic rights for every citizen of this land. I am doing it for one reason because it is right. And I am doing it in the name of millions of Americans, both white and Negro, who object to treating their fellow citizens one way on the battlefield and another way in the country that they're fighting to defend.

Narrator: In 1967 President Johnson proposed to ban racial discrimination in housing. His Fair Housing bill came to the floor for a vote on April 10th. Once again the race issue would force George Bush to take a stand.

George H. W. Bush (archival): You got to wrestle with your conscience. You got to listen to people. It doesn't come so easy to me that this is right and that's wrong. It's never that simple. The tough votes are the ones you agonize over and then you do what you think is right.

Narrator: Bush did not vote as a Goldwater Republican. He supported Lyndon Johnson. Many in his district were outraged.

Doro Bush Koch, daughter: Dad got a lot of death threats. People called up on the phone. Velma Johnson, an African American staff member in my dad's office, picked up the phone, and the person on the other end was rambling and screaming ugly, nasty things. Tears were streaming down her face. My dad grabbed the phone from her and said, "I don't know who this is. This is George Bush. Don't you ever call here again and treat anyone on my staff like that again."

Marjorie Arsht, political supporter: He was threatened and denounced, and vilified for having betrayed his political constituents. And there was one woman who had been a big supporter of George's. And she wrote him a letter and said that she felt that she'd been violated, and that he would never be welcome in her house again.

Robert Mosbacher, political supporter: Mainline Republicans in those days were against open housing. And they were absolutely convinced that they were against him, would never vote for him, would vote for recall. I offered to talk to some of his main money backers, because a lot of them were furious at him. And he said, "No, no. Just get them together and I'll talk to them."

Narrator: Bush prepared to meet not just his funders but the rank and file.

Chase Untermeyer, Congressional intern: He said that he was going to face a angry crowd and that he was being fitted for iron underpants for whatever they might decide to do when they had him on the griddle.

Narrator: On April 17, 1968, Congressman Bush addressed a hostile audience of 400 at Houston's Memorial High School.

Peter Roussel, press aide, 1970-74: There were boos, hisses. It was ugly. There was sheet lightning in that auditorium that night. They were out to get George Bush. They were unhappy with George Bush. It was not a pretty scene.

Marjorie Arsht, political supporter: I thought my heart would just really stop. I was so afraid of what might happen. People said he ought to be killed.

Peter Roussel, press aide, 1970-74: Once all the hubbub died down, he defended his vote on that piece of legislation.

Narrator: "Your representative owes you not only his industry, but his judgment," Bush told his audience, quoting 18th century philosopher Edmund Burke, "and he betrays instead of serving you, if he sacrifices his judgment to your opinion. I voted from conviction," he explained, "not out of intimidation or fear but because of a feeling deep in my heart that this was the right thing for me to do." Earlier that year, Bush had visited U.S. troops fighting in Vietnam.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: When he went to Vietnam in 1968, he came back with a very strong sense of outrage that although blacks were so prominent in the American military, and so prominent among those who were giving their lives, that they were treated so poorly in this country.

Narrator: Now, Bush asked his audience, "How would you feel about a black American veteran of Vietnam returning home, only to be denied the freedom that we, as white Americans, enjoyed? Somehow it seems fundamental that a man should not have a door slammed in his face because he is a Negro or speaks with a Latin American accent."

Peter Roussel, press aide, 1970-74: And I'll tell you by the time that speech was over, the atmosphere in that auditorium had changed considerably. It had transformed.

Marjorie Arsht, political supporter: It was one of the few times I ever saw a few words completely transform an audience. It was probably one of the most dramatic incidents in all of George's public life, including when he was president.

Narrator: Tonight I got on this plane," Bush wrote a friend, "and this older lady came up to me. She said, "I'm a conservative Democrat from the district, but I'm proud, and will always vote for you now," and suddenly somehow I felt that maybe it would all be OK -- and I started to cry -- with the poor lady embarrassed to death." More than 20 years later, Bush would write, "I can truthfully say that nothing I've experienced in public life, before or since, has measured up to the feeling I had when I went home that night." Once in office, George Bush tended to follow his conscience. That night in 1968 he put his political future at risk. It worked. He would not always be that lucky.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: Bush was portrayed in some aspects of the media as an up-and-coming romantic hero. The future, romantic future of the Republican Party. Young, good-looking guy, full of energy, with a devoted wife and children. It was a good package.

Narrator: In 1970 President Richard Nixon asked Bush to run for Senate -- again against Ralph Yarborough -- promising him a job if he lost. Bush's House Seat was secure. He was a member of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, and he was torn. He had often reached across the aisle to vote for legislation important to his fellow Texan President Johnson. Now he consulted LBJ. "Son," Johnson said, "I've served in the House, and in the Senate too, and the difference between being a member of the Senate and a member of the House is the difference between chicken salad and chicken shit. Do I make my point?"

Doro Bush Koch, daughter: My dad chose the chicken salad.

George H. W. Bush: Today I am announcing my candidacy for the United States Senate. It hasn't been an easy decision. I have been very happy in the House of Representatives. I have been particularly happy...

Peter Roussel, press aide, 1970-74: There were high hopes for him in that race. It was one of the premier races of that year, and a lot of people thought, well, Bush is going to win this Senate race, and there's probably a good chance that'll be the stepping stone for him ultimately going to run for president.

Narrator: Bush asked his friend James Baker, a prominent Houston lawyer with deep Texas roots, to run his campaign.

James A. Baker, III, friend: I lost a wife to cancer when she was only 38 years of age. And George Bush was my tennis doubles partner, and he came to me and he said, "Bake," he said, "you need to take your mind off your grief. How about helping me run for the Senate?" And I said, "Well, George, that's great except for two things. Number one, I don't know anything about politics." I'd never done anything in politics. "And number two, I'm a Democrat, and he said, "we'll take care of that." And we did. And I changed parties.

Narrator: Bush had confidence he could beat Ralph Yarborough this time -- Texas was growing more conservative. Then Lloyd Bentsen, a businessman more conservative than Bush, challenged Yarborough in the Democratic primary and won. The Nixon White House moved into action.

Richard Nixon (archival): We have to think in terms of what is best for America and it's because I believe that George Bush will do better for Texas and better for America, that I'm for George Bush for the United States Senate.

Narrator: Despite the endorsement, White House staff considered Bush too tame a candidate.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: They considered Bush loyal, a source of money, but basically weak. He didn't have the drive to play the game the way they wanted it played. He was too much the gentleman. The aristocratic gentleman. And that's what Prescott Bush was.

Narrator: Many of Yarborough's liberal Democratic supporters considered Bush a more attractive candidate than Bentsen. But the polarizing presence of Nixon convinced them to vote against Bush.

Peter Roussel, press aide, 1970-74: Early on, the networks called it for Lloyd Bentsen. And I was up in the suite with him there, and he just kind of sunk deeper and deeper into the couch there. And finally somebody said, "It's time to go downstairs and concede." And he felt pretty low.

George H. W. Bush (archival): And nobody likes to lose, but certainly he ran a good tough race. I feel kind of like Custer, There were too many Indians. Well, there are too many Democrats in some of these counties I guess. The other thing is that I have a horrible problem between now and kind of figuring this thing out, because I can't think of anyone else to blame. Thank you very much.

Lud Ashley, classmate: He was brought up not to show great disappointment in defeat or great glee in victory. But he doesn't like to lose. He does not like to lose.

George H. W. Bush: I think in defeat you grope for things that are happy, and it's hard. But I think I would be less than frank if I said I felt good or could see anything from a personal standpoint to be excited about at this point. We're hurt and we lost. We wanted to win.

Narrator: With two unsuccessful Senate campaigns, Bush's political future was in doubt. For the next 18 years, George Bush would not be in control of his political career. He would try to advance his career by serving others in administrative posts, to which he was well suited, but which, to many, seemed a dead end. When Nixon offered Bush an insignificant job as assistant to the president, Bush made his case for more.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: He said, what this administration needs is someone who could strongly represent the administration not only in the United Nations but in New York, and who would have clout in the social society of New York. And I'm your man.

George W. Bush (archival): The relief for me is really great just to know that my family is so happy after a kind of a tough defeat in November but now, you know, a new life and a new vigor has kind of sprung back into our veins.

George H. W. Bush (archival): I, George Bush, do solemnly swear...

Lud Ashley, classmate: I wondered how on earth he could be appointed to the United Nations with as little foreign policy experience or knowledge that he had at that time. And I asked him about that. I said, "What the hell do you know about foreign policy? And he just gave me this big smile and he said, "You ask me in a month."

Chase Untermeyer, reporter, Houston Chronicle At the time a lot of people, myself included, thought, well, this is the end of the road. Because what does it mean to be ambassador of the United Nations? That is certainly not a way to get any vote in Texas.

Narrator: Bush plunged with relish into the organization that he had denounced in his '64 campaign. He knew little about foreign policy, a lot about dealing with people.

Timothy Naftali, biographer: From the time Bush became the U.S. permanent representative to the United Nations, he began to collect foreign friends. Leaders, soon to be leaders, deputies, ambassadors, foreign ministers. He was very good at empathizing with them. In fact, at the United Nations, he developed friendships with people who didn't like U.S. policy.

Brent Scowcroft, National Security Advisor, 1989-93: He started a practice of walking down the halls and dropping in on his fellow ambassadors, just to say, "How are you? How are things in your country? What do you think of the United States? What do you think of the UN? What are the problems of the world as you see them?" And he developed that into a fine art.

Peter Roussel, press aide, 1970-74: He's a master of the personal touch. He's an incredible "thank-you" note writer. He would meet somebody somewhere, and the next day they'd have a little note in the mail: "Thank you, Joe. I enjoyed meeting you." You'd say, "Here's somebody took time to write me a thank-you note." Who does that anymore?

News anchor (archival): Five men wearing white gloves and carrying cameras were caught earlier today in the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in Washington. They apparently were unarmed and nobody knows yet why they were there.

Narrator: In November 1972, just shy of two years on the job, Bush was summoned to Camp David. It was five months after news reports at the Democratic Party election headquarters at the Watergate Hotel. "George," Bush recalled Nixon saying, "the place I really need you, is over at the National Committee running things. This is an important time for the Republican Party, George. We have a chance to build a new coalition in the next four years, and you're the one who can do it."

Barbara Bush, wife: I sent him off saying, "Under no circumstances be Republican National Committee Chairman. It's just a no-end job. You'll be gone all the time. Please don't do that." So he went, and because he believes you never say no to a president, when President Nixon asked him to do that, he said yes.

George H. W. Bush (archival): What I want to do is build the party in a constructive positive image. The president is setting a good program for this. Our challenge is to implement it and to have room for diversity and to have room for growth, and I've got to go.

Lud Ashley, classmate: I said, "You've got this all wrong. I don't know what's happened to you, but you don't go from-from being the President's man at the United Nations to being chairman of a political party. You're coming down the ladder," and I said, "that's the wrong direction."

John Robert Greene, presidential historian: Nixon knew that it was about to hit the fan, and George Bush could be counted on for absolute loyalty in front of a camera. Nixon knew instinctively that as Watergate unfolded, as the disaster began to build, Bush could be counted on to stick by Nixon right through until the bitter end.

Narrator: Less than a month after Bush took the job, the Senate established a Watergate Committee to hold hearings on the break-in.

Senator Ervin: ...begins hearings into the extent to which illegal, improper and unethical activities were involved in the 1972 presidential election campaign.

Narrator: As the scandal unfolded, Bush traveled to 33 states and made 190 appearances defending the president and the Republican Party.

George H. W. Bush (archival): As you look across the country, the Watergate has not obscured the positive record of this administration.

John Robert Greene, presidential historian: When he goes out in front of a television camera for Richard Nixon, George Bush has the perfect public face. The other part about Bush that the Nixon White House liked was his combative nature with the press. And the press was just beginning to feel its oats in 1973. Bush was not going to let them get away, in his mind, with this type of picking on the President.

George H. W. Bush (archival): The President has said that he is not involved in Watergate. That he didn't know about it, that he is not involved in the cover up. And I accept that, and I don't think it helps the stability of the forward progress of the country to speculate hypothetically when the man had made that statement.

Barbara Bush, wife: Nixon lied to George. George couldn't believe someone would look you in the eye and say, "I had nothing to do with this. I have not lied."

Peter Roussel, press aide, 1970-74: I can remember, because I was there with him, I can remember many of our friends and, you know, wise men and politicos that were around then, saying, "That's the end of Bush's career. That's the end of George Bush. His time's over." And certainly the media had written him off.

Chase Untermeyer, presidential aide, 1989-91: I think of all the things that George Bush did prior to being asked to run for vice-president with Ronald Reagan, being chairman of the Republican National Committee during Watergate was the most valuable, because during that miserable time for grassroots Republicans, there was George Bush keeping up the faith and trying to keep people's spirits up.

Senator Howard Baker (archival): Tell me what the president knew and when he first knew it.

John Dean (archival): At a meeting on September 15th ...

Narrator: Testimony from Nixon staffers on June 3, 1973 marked the beginning of revelations that would bring the President down. "I've never seen such an unhappy man as George was during this period," a White House insider recalled. "because now all of us had come to the conclusion that we'd all been lied to for many, many months." Bush fumed in his diary, "This era of tawdry, shabby lack of morality has got to end," Bush wrote in his diary. "I am sick at heart. Sick about the President's betrayal and sick about the fact that the major Nixon enemies can now gloat because they have proved he is what they said he is."

Herbert Parmet, biographer: Bush was caught up in it. Bush was embarrassed by it, and the thing he told me embarrassed him most of all was, he had given assurances to fundraisers that Nixon was not involved. Nixon let him down.

Narrator: On August 6, 1974 Bush attended a cabinet meeting. Nixon's agenda was to talk about the economy.

John Robert Greene, presidential historian: Ford turned to the President and said, "We have other issues that we have to discuss. We have to discuss the fate of this presidency." George Bush stood up, interrupted Nixon and told him that Watergate was sapping public confidence in the party and the county. The next day he advised Nixon to resign. "Dear Mr. President," he wrote, "I expect in your lonely embattled position this would seem to you as an act of disloyalty from one you have supported and helped in so many ways." George Bush had accepted the party chairman's job because of his loyalty to Nixon. That loyalty, Nixon found to his dismay, had its limits.

Narrator: In August 1974, Bush retreated to Kennebunkport.

Barbara Bush, wife: Here he feels at peace. It's roots of his family. His mother was born here. He'll tell you it's CAVU. Now, I never can remember what that means, but it's Ceiling And Visibility Unlimited. And that's what he feels about Kennebunkport, Maine. He's at peace here.

Narrator: President Gerald Ford, Nixon's successor, was about to choose his vice-president. Bush was the first choice of party leaders. At Walker's Point, he anxiously awaited the news.

Willard "Spike" Heminway, friend: Barbara Bush called up, says, "Come on over. Got to do something with George. He's getting finicky over here." So I go over, and there he is underneath the toilet, fixing toilets. And I said, "Is this the way a potential vice-president's going to act?" And he said, "Get in here and help me fix these toilets."

Narrator: Ford called him to say he has selected former governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller. "Yesterday was a real downer," Bush wrote Lud Ashley. "I guess I had let my hopes zoom unrealistically, but today perspective is coming back, and I realize I was lucky to be in the game at all."

Lud Ashley, classmate: It's his way of relaxing. And it's nonstop. It's just from-from one event to the other. I often say that in his crankcase, there's no reverse. There's no neutral. There's just drive. [laugh] And that's all there is in his crankcase. He's just always on the go.

Narrator: Ford offered Bush another ambassadorship. He could have chosen England or France, but he chose China. A friend recalled, "he wanted to get as far away from the stench of Watergate as possible." After little more than a year, another odor wafted his way. Congress was investigating CIA abuses.

Senator Frank Church (archival): We must insist that these agencies operate strictly within the law...

Narrator: The Bushes were bicycling in Beijing when a cable arrived from Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Would Bush take over the CIA?

Barbara Bush, wife: It just was a huge shock. And George got the message, and then he called George W. and said to him, "George, please call your brothers and sisters," and see how they'd feel about my coming home and heading the CIA." And George called back in about an hour and said, "They say, come home." And I've always thought George never called them. That he just decided arbitrarily that we should come home. And I thought then that this was the end of politics, that this would be just the end of our political life.

Narrator: "Here are my heartfelt views," Bush cabled Kissinger, "I do not have politics out of my system entirely and I see this as the total end of any political future." But "If this is what the President wants me to do the answer is a firm 'Yes.'"

George H. W. Bush (archival): Some of my friends have asked me, "Why do you accept this job with all the controversy swirling around the CIA with its obvious barriers to political future?" My answer is simple. First, the work is desperately important to the survival of this country and to the survival of freedom around the world. And second, old fashioned as it may seem to some, it is my duty to serve my country. And I didn't seek this job but I want to do it, and I will do my very best. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Narrator: Bush found CIA staffers demoralized. "We did have the feeling we were terribly alone, and there was no one out there defending us," one remembered. "George became a champion." Bush saw his job as boosting morale at CIA headquarters and reassuring Congress that the "rogue elephant" was under control.

George H. W. Bush: I can say, sir, that we would not disseminate that kind of intelligence on American citizens to the Cabinet committee, but we would disseminate it to the Justice Department.

Narrator: He made 51 appearances on Capitol Hill in less than a year.

After six months on the job he wrote President Ford: "Morale at the CIA is improving. Our recruitment is up. Our people are willing to serve abroad and take the risks involved."

When Jimmy Carter was elected President in 1976, Bush offered to remain at the CIA to burnish the agency's reputation as bipartisan.

News announcer (archival): There is increasing speculation that CIA Director George Bush may be asked to stay at his post during the new administration, but as he arrived today, he and Carter aides all refused comment on that.

George H. W. Bush (archival): I'm going to use the same ground rules that we had before, which is we're here to have a professional intelligence briefing.

Narrator: Bush became the first CIA director to be dismissed by an incoming president.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: Here was Bush, having made this concession in order to reaffirm the CIA post as being non-political, only in the end to see himself forced out because of the advent of a new administration. Well, Bush was determined to fight back, and fight back into the political arena.

Narrator: Demoralized, George Bush returned to private life in Houston. "He felt like a race horse under wraps," a biographer wrote. Bush described his "withdrawal symptoms" to a friend. "I just get bored silly about whose daughter is a Pi Phi or even about who's banging old Joe's wife," he wrote. "I think I want to at least be in a position to run in 1980. But it seems so presumptuous and egotistical." George did his best to drown out his mother's voice. For two years he served on corporate boards and built his war chest for a presidential campaign. "He is finally getting better about blowing his own horn," Barbara wrote, "the thing we were taught as children never to do."

On May 1 1979 George H. W. Bush returned to Washington.

George H. W. Bush (archival): Ladies and gentlemen, I am a candidate for president of the United States. Before responding to questions, I would like to introduce you to my family. My mother, Mrs. Prescott Bush, who some of you may remember. My wife Barbara, most of you know. My oldest son George and his wife Laura, from west Texas. My son Jeb, his wife Columba from Houston, Texas.

Narrator: Bush distanced himself from the Republican front-runner, Ronald Reagan, the conservative governor of California, by invoking language used by President Eisenhower.

George H. W. Bush (archival): There is in our affairs at home a middle way between the untrammeled freedom of the individual and the demands for the welfare of the whole nation.

Narrator: In one year Bush traveled 329 days calling in all his chits from his years at the Republican National Committee. In a surprise victory, George Bush defeated Reagan in the Iowa caucus.

George H. W. Bush (archival): Iowa has set something in motion. The forward momentum is clearly established, and I am absolutely convinced I will be your next President.

Narrator: In the important New Hampshire primary, Reagan challenged Bush to a one on one debate and agreed to pay the cost of the event. At the last minute, in a clever ploy, Reagan wanted to change the rules to include the other candidates. Bush -- and the moderator -- stuck to the original agreement.

Ronald Reagan (archival): Mr. Breen. If you ask me if you--

Moderator (archival): Can you turn off that microphone please?

Ronald Reagan (archival): I am paying for this microphone, Mr. Green.

Narrator: That night George Bush learned how formidable a candidate Ronald Reagan could be.

Timothy Naftali, biographer: George Bush is like a boy who's dropped off at the wrong birthday party. He's just so awkward and doesn't know what to do, and he looks a little bit miffed.

George H. W. Bush (archival): I have been invited here as a guest of the Nashua newspaper. I will play by their rules. I am their guest, and I am very glad to be here. Thank you very, very much.

Narrator: Bush lost New Hampshire, but continued to challenge Reagan -- ridiculing his so-called "supply side" tax policy -- the notion that taxes could be cut without reducing spending.

George H. W. Bush (archival): This theory that Governor Reagan is talking about is what I call a 'voodoo economic' policy.

Narrator: Reagan appealed to staunch anti-communists and social conservatives, two of the groups Bush welcomed into the Republican Party in Harris County almost 20 years before. As a moderate, George Bush was chasing the caboose of the party he had helped to create. By May campaign manager James Baker urged him to pull out.

James Baker: Reagan had-had collected sufficient number of delegates to be- to be nominated, and my advice to George at the time was that we ought to fold up our tent, and not go out to California and try and contest Reagan in his home state, because if we did that, there'd be no chance whatsoever that he would be put on the ticket.

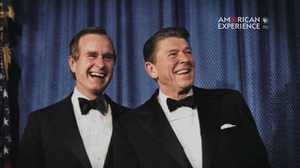

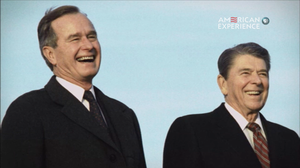

Ronald Reagan: I have asked and I am recommending to this convention that tomorrow, when the session reconvenes, that George Bush be nominated.

Narrator: In many ways George Bush was what Ronald Reagan pretended to be. As an actor, Ronald Reagan played the war hero. George Bush was a war hero -- a decorated naval aviator. Ronald Reagan played the athlete. George Bush was the captain of his Yale baseball team and played twice in the college championship game. He was also a first rate tennis player. Both preached family values, but only Bush could point to a happy family. Reagan turned to Bush because he wanted to unify the conservative and moderate wings on the party and because Bush was the only other candidate to win any delegates.

Richard Norton Smith, presidential historian: Reagan took him in spite of his doubts. He had seen Bush at his worst. He had seen Bush, in effect, wilt under pressure at the famous Nashua debate. And he didn't like what he'd seen. More than that, Bush had come up with some very powerful phrases, including "voodoo economics," that in effect trivialized Reagan's beliefs.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: Reagan disliked him for using the term "voodoo economics;" he disliked him, Reagan thought he was a wimp; Nancy detested him bitterly. Reagan did not turn to Bush happily, and when I said to Bush was there anything Reagan asked of you in order to nominate you as Vice President, he simply said he wanted me to accept his position on abortion, which I did.

Narrator: Despite their political differences, Bush pledged his loyalty.

Shirley Green, press aide: I will never forget the very first staff meeting we had, before they were even sworn in. Ambassador Bush really kind of laid down the rules to us. And he said, "I don't want to ever pick up the paper and see any suggestion that anybody on my vice-president staff has been anything but loyal to Ronald Reagan."

Narrator: Bush's experience in foreign affairs was especially useful to Reagan. His connections with Deng Xiaoping helped ease tensions over arms sales to Taiwan. His message in El Salvador was stop the right wing death squads or Congress will cut off aid to fight communist insurgents. To Communist Poland he brought a message of freedom.

George H. W. Bush (archival): Poland should be strong and prosperous and independent and play its proper role as a great nation in the heart of Europe.

Narrator: When three Soviet presidents died in less than three years, Bush was the first among world leaders to greet the new leader after the funeral. He would explain America's policies and report directly to Reagan. Bush's deep interest in foreign policy served him well -- until a report broke that the Reagan administration was secretly selling arms to Iran to get its help in releasing hostages held in Beirut, a violation of its own policies.

George H. W. Bush (archival): I was aware of our Iran initiative and I support the president's decision.

Narrator: More serious was the charge that the administration illegally used profits from the arms sales to fund the anti-communist Contras who were trying to topple the Marxist government in Nicaragua. It became known as the Iran Contra affair.

George H. W. Bush (archival): And I was not aware of and I oppose any diversion of funds, any ransom payments, or any circumvention of the will of the Congress or the law of the United States of America."

Narrator: What Reagan may have told his vice president during their Thursday lunches or what advice Bush may have given his president was something both considered confidential. As the scandal unfolded, the former Director of Central Intelligence would be under suspicion that he was involved in more than he let on.

George H. W. Bush (archival): There's no question about trying to jump away from it. I support the President.

Reporter (archival): Mr. President, what do you know about money going to the Contras?

Ronald Reagan (archival): All I know is this is going to taste wonderful, and I'm looking forward to tomorrow.

Reporter (archival): Mr. President, hasn't this damaged your presidency?

Narrator: This was nothing new. Cartoonist Garry Trudeau had caricaturized Bush's loyalty as "putting his manhood in a blind trust." As Bush planned his run for the presidency, conservative columnist George Will called him a "lap dog" for trying to prove to conservatives he was Reagan's heir.

George H. W. Bush (archival): I am here today to announce my candidacy for President of the United States.

Narrator: The week he announced in October 1987, Newsweek called him a wimp.

Evan Thomas, Newsweek: That's an awful word to use, and we used it on the cover of Newsweek, I think, to our regret. It was too harsh a word. But there was a perception that he was somehow not a standup guy. He was under Reagan's shadow, and he needed to win over the true right and evangelicals, and to do that, he seemed to be trimming a little bit on abortion, he seemed to possibly be going against his own conscience in order to win votes.

Narrator: Bush lost to Sen. Bob Dole in the Iowa caucus in February 1988. His own polls said he was perceived as a follower, not a leader; a man who would not be tough enough for the Oval Office. He was trailing Dole in the critical primary in New Hampshire. A loss could mean the end of his presidential hopes. Yet he remained hesitant to say anything bad about his opponents.

George H. W. Bush (archival): I'm not taking shots at the other candidates. I'm not trying to get myself up a notch on the ladder by shoving somebody else down on the ladder, whether it's a candidate or the president of the United States or anybody else. I just don't believe that's the way one oughta campaign, I've never don't that. And so I feel comfortable saying what I am for.

Craig Fuller, chief of staff: Well, he'd been the chairman of the Republican National Committee. He didn't speak ill of other Republicans. He believed that he had to talk about his record, his experience, his ability to be president, and let people make their mind up. He was less inclined to talk about his challengers at all, really.

Narrator: "You got to go negative," Bush's new campaign manager Lee Atwater told him. "You just got to." Atwater was a new breed of political consultant. Known as the happy hatchet man, he set out to completely change Bush's gentlemanly campaign style.

John Robert Greene, presidential historian: Atwater, was able to articulate a side of George Bush that needed to be articulated if he was to win. And that was the harsh side of Bush. Bush doesn't naturally gravitate to bare-knuckle politics. He needs to be taken there. Atwater did that.

Narrator: Atwater's team had put together a campaign spot attacking Senator Dole. Bush rejected it.

Robert Mosbacher, campaign aide: I told then Vice-President that just sometimes you have to kind of leave the high road. And he sort of oomphed and you know said, "All right, let me look at it again." He said, "All right. I don't like it, but okay. But it better all be true."

Announcer, Bush campaign ad: Bob Dole straddled until the polls told him it was popular. That's why he's becoming known as "Senator Straddle." George Bush: presidential leadership.

Narrator: The new strategy worked. Bush won in New Hampshire...

George H. W. Bush (archival): And now, on to the South where we're gonna rise again.

Narrator: ...and went on to secure the Republican nomination.

Narrator: In May he trailed Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, the Democratic nominee, by 10 points. The blue collar Democrats who had flocked to Ronald Reagan were supporting Governor Dukakis. The Bush campaign team needed to woo them back. It was encouraged by a blue-collar focus group that showed Dukakis had a weak spot. He was perceived as a liberal.

Mary Matalin, campaign aide: Lee Atwater knew that that sort of east coast, elite, liberal ideology and persona was going to be problematic for Dukakis. So showing that is part of how campaigns work. This is what campaigns do.

Narrator: Bashing Dukakis would become the focus of Bush's campaign.

George H. W. Bush (archival): Governor Dukakis, his foreign policy views born in Harvard Yard's boutique would cut the muscle of our defense and I will never do that.

Nicholas Brady, campaign aide: I don't think by nature he likes to go negative. He-- that's not the way he was, not the way he was brought up.

George H. W. Bush (archival): The governor calls himself, and this is a quote from Michael Dukakis, a card-carrying member of the ACLU, American Civil Liberties Union. I haven't joined the ACLU nor do I have any plans to join the ACLU.

Nicholas Brady, campaign aide: He may not have liked it, but it isn't as if you were trying to make him take a drink of castor oil or something like that. He knew exactly what had to be done in the long run.

Richard Norton Smith, presidential historian: Prescott Bush's son is not comfortable with the culture of handlers and spin doctors and pollsters and focus groups, and determining what your convictions are by asking a group of strangers in a supermarket in Secaucus, New Jersey. On the other hand, he'll do it if that's what it takes to win the presidency.

George H. W. Bush (archival): Thank you, I accept your nomination for President. I'll try to be fair to the other side. I'll try to hold my charisma in check. Where is it written that we must act as if we do not care? As if we are not moved. Well I am moved. I want a kinder, gentler nation.

Narrator: That phrase, Bush thought, would appeal to moderates turned off by Reagan's harsh edges. Another line, from a Clint Eastwood movie, would counter the wimp factor and project an image of strength.

George H. W. Bush (archival): The Congress will push me to raise taxes, and I'll say no, and they'll push, and I'll say no, and they'll push again, and I'll say to them, "Read my lips, no new taxes."

Nicholas Brady, campaign aide: It appealed to his sense of good fun. And he did it with gusto, and of course it knocked the ball out of the park.

Richard Darman, campaign aide: I thought it was ill advised, and I argued against keeping it in. The "no new taxes" part was going to be very difficult to live with.

John Robert Greene, presidential historian: It was the single best speech of Bush's career. It was Bush at his most animated. It was Bush at his most telegenic. The camera does not love George Bush instinctively. He never did any better than-than this speech, even as president.

Narrator: Bush had cut Dukakis's lead in half. After Labor Day the attack on Dukakis intensified.

Announcer, Bush campaign ad: Dukakis not only opposes the death penalty, he allowed first degree murderers to have weekend passes from prison. One was Willie Horton, who murdered a boy in a robbery stabbing him 19 times. Despite a life sentence, Horton received ten weekend passes from prison. Weekend prison passes. Dukakis on crime.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: The official Republican campaign did not resort to those scare ads. But there was another committee, that used the menacing black face of Willie Horton but it would be very hard for you and me to really disassociate those two.

James Baker: Now, there was an independent group that ran an ad with Willie Horton's picture, which we finally got them to stop running.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: Baker writes a letter asking them to cease and desist from the use of the racial attacks, scare attacks about Horton. The damage has already been done.

Narrator: The offending ad played for 25 days before it was yanked. Then campaign manager Baker launched the authorized one.

Announcer, Bush campaign ad: His revolving door prison policy gave weekend furloughs to first-degree murderers not eligible for parole. While out, many committed other crimes like kidnapping and rape. Now Michael Dukakis says he wants to do for America what he's done for Massachusetts. America cannot afford that risk.

James A. Baker, III, friend: That was not going negative. Governor Dukakis supported a prison furlough bill as governor of Massachusetts. And all we did was point out that he had done that.

Michael Dukakis (archival): Yes it was a terrible human tragedy. And I accepted responsibility for it. And changed the program.

Evan Thomas: One of the ironies of George Bush's life is that a fundamentally decent man presided over a moment when politics got meaner and rougher. '88 was the year of the handler, of bringing in political consultants who played very hard and very tough. Now, they'd always been around in politics. They weren't invented in 1988. But 1988 was kind of a rough, trivial campaign. Lee Atwater and these henchmen for Bush looking for the so-called wedge issues, not really staying on the high road and talking about the great issues of the day, but rather sniping at their opponent to find some weakness in him. And Bush put up with that.

Sam Donaldson (archival): Did you see in the paper that Willie Horton said if he could vote he would vote for you?

Michael Dukakis (archival): He can't vote Sam.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: I think it was one of the dirtiest campaigns in American history. The whole concept of smearing the term liberalism. The whole concept of making that into a dirty word -- the L word. He made his compromise, just like his made his compromise with Reagan, saying yes, he'd be against all abortions. George is pragmatic. You have to win in order to put your principles into effect. Without winning, you can't achieve anything. These are the accommodations that George had to make for politics.

Narrator: In November 1988 George Herbert Walker Bush soundly defeated Michael Dukakis to become the first sitting vice president since Martin Van Buren in 1836 to be elected president. Ronald Reagan, who had doubts about Bush eight years earlier, came to feel he was the most qualified president-elect in American history. They became good friends. When Bush went to the Oval office for the first time as President, a note from Reagan read: God bless you and Barbara. I'll miss our Thursday lunches. You'll have moments when you want to use this stationery. Bush placed the note in his desk. On the desk he placed a picture of Robin. They would remain there for his entire term in office. The first photo was with his mother. His competitive spirit had come from her. And his sense of modesty. She had taught him never to call attention to himself. Yet for eight years he had seen Reagan inspire Americans with a sense of drama and celebratory spectacle. Reagan's conservative revolution had swept him to the national stage. George H. W. Bush was Ronald Reagan's heir.

Richard Viguerie, conservative activist: He spent the entire eight years as vice president traveling the length and breadth of this country, saying "trust me, I am a conservative, and if I am ever elected president of the United States I will govern as a conservative." We didn't expect him to be another Ronald Reagan, but we did expect that he would keep his clear promises and he would govern as a right-of-center president.

Narrator: Bush was Ronald Reagan's heir. He was Prescott Bush's son.

Richard Norton Smith, presidential historian: There you have the conundrum of the Bush Presidency. He was looking over one shoulder and seeing where the Republican Party was going. And over the other shoulder, he saw his own lineage, his own tradition. He saw his father, Prescott Bush. He saw Dwight Eisenhower. And he saw Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, who in retrospect are seen as moderate conservatives.

Narrator: Now, with a chance to be his own man, George Bush began to distance himself from Reagan.

John Robert Greene, presidential historian: First thing that he does is -- through his transition team, which was run in part by his son, George W., was went in and booted all of the Reagan appointees, and told them, with a great deal of harshness, that they were to be out of town before sundown. It was an ideological housecleaning, and Reagan appointees are shown the door, in a harsh transition that makes it look like a Democrat is coming in.

Narrator: Wasting little time, Bush tackled some of the problems he inherited. On the domestic front, he decided to clean up a messy banking problem that Reagan and Congress had all but ignored. In 1986, when the real estate market collapsed, hundreds of savings and loan banks had gone bust. The cost of bailing out depositors was pushing $50 billion and was projected to triple. Bush knew it would be expensive and politically thankless.

John Robert Greene, presidential historian: You do it, not to advance your interests. You do it because it's in the interest of millions of people who will never vote for you and will certainly never give you any credit for doing it. That's responsibility. That's accountability. That's the old establishment way of discharging the privileges of leadership.

Herbert Parmet, biographer: He's separating himself from Reagan. One of the things that haunted Bush all the way through was his being compared to Reagan. And immediately, from his acceptance speech, "a gentler and kinder country," he's separating himself from Reagan. And this was some of the major residue of the Reagan administration.

Narrator: In Nicaragua, he agreed to withdraw support from the counter-revolutionary Contras if the Marxist Sandinista government agreed to free elections.

Timothy Naftali, biographer: President Bush began to act quite differently from Candidate Bush. One of his first initiatives was to push for elections in Nicaragua, and to take Nicaragua off the front burner of U.S. foreign policy. He didn't want to continue the divisive American debate.

Narrator: Bush also confronted the question of how to deal with a rapidly changing Soviet Union. Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev had pledged at the United Nations to renounce the use of force and withdraw one-half million troops from Eastern Europe. Many Russian experts felt the Cold War was over -- even the "Wise Man" who 45 years earlier had devised the policy of containing the Soviet Union.

Colin Powell: President Bush came into office realizing a lot had been done under President Reagan, but there was still a Soviet Union. It hadn't gone away. It still had all of its missiles. It still had its troops, and so it wasn't entirely clear what was going to happen. Mr. Gorbachev was a very charismatic figure, but it wasn't clear whether or not he had the whole Soviet governmental structure with him, governmental structure with him. And so there was the degree of caution and a degree of, let's study this.

Narrator: Four months into his term, Bush responded to Gorbachev.

George H. W. Bush (archival): Ultimately, our objective is to welcome the Soviet Union back into the world order. Containment worked and now is the time to move beyond containment to a new policy for the 1990s -- one that recognizes the full scope of change taking place around the world and in the Soviet Union itself.

Narrator: The response, many felt, was too timid. A New York Times editorial said if an alien spacecraft landed and looked for earth's leader, it would be taken to Mikhail Gorbachev.

Pavel Palazchenko, Foreign Ministry, Soviet Union: Gorbachev was encouraging reforms, definitely. And he believed and said that if we wanted change in our country, if we wanted to abandon the old system in our country, how could we prohibit or inhibit change in our neighbors?

Narrator: Bush did not meet the Soviet leader for almost a year. He did respond to the changes Gorbachev had encouraged in Eastern Europe. In Poland the anti-government Solidarity movement routed the Communists in free elections, the first break in the Iron Curtain in more than 40 years. The challenge for Bush when he arrived in Warsaw in July 1989 was not to provoke a backlash by Poland's communist leader Gen. Jarezelski or Kremlin hardliners.

George H. W. Bush (archival): Thank you, Mr. Chairman, for your hospitable and gracious words of welcome. We extend the heartfelt best wishes of the American people, and here in the heart of Europe, the American people have a fervent wish -- that Europe be whole and free.

Narrator: Bush spent time with Poland's reform leader Lech Walesa. He spent more time with Jaruzelski.

John Sununu, Chief of Staff: The President, I think, really understood that a lot of the folks that were there doing the Russians' bidding were still Poles first, and cared about their country. And he tried to create a structure in which the strong hand, supported by the Soviet Union, became a part of the solution rather than opposition to the solution.

Condoleezza Rice, Soviet expert, National Security Council: He was determined that no one was going to feel that they had been defeated. He was very aware, I think, of the Versailles syndrome that Germany had felt defeated after World War I, humiliated after World War I, and that had brought to power Adolf Hitler.

Timothy Naftali, biographer: He saw what was going on in Eastern Europe as a very delicate process that involved holding the hands of both the reformers and the old style communists.

John Sununu, Chief of Staff: It was an art form that George Bush was very good at. He understood the- that most people generally have good intentions. You just have to find a way to get them to work together in order to bring them forward.

Narrator: Bush encouraged the reforms Gorbachev had allowed. His active role came after the reform movement spread to East Germany. In August East Germans sought asylum at the West German missions in Prague and in East Berlin. Then Hungary opened its borders to Austria, and East German tourists fled into Austria. As protests for reform grew in East Germany, the British and the French grew more worried about a reunified Germany. In the first half of the 20th century they suffered from German aggression in two world wars. In the second half, with Germany divided, Europe had been at peace. The possibility of a reunited Germany almost 50 years after Hitler did not worry George Bush.

Reporter (archival): Mr. President, do you think a reunified Germany would be a stabilizing force in Europe or a destabilizing force?

George H. W. Bush (archival): I think there is in some quarters a feeling a reunified Germany would be detrimental to the peace of Europe, of Western Europe in some way, and I don't accept that at all, simply don't.

Narrator: They "can't turn back the clock", Bush told the New York Times. "The change is too inexorable." One writer called this a "verbal volley heard around the world."

Condoleezza Rice, Soviet expert, National Security Council: His pronouncements before the wall came down were probably among the most unstaffed comments by any president of the United States. I can tell you that was wonderful, to have the President come out and say, "Germany ought to unify, and unify as quickly as it can, on terms that are acceptable to Germans." Because we didn't have any debates inside the administration about whether Germany ought to unify. The President had already said it was going to unify. Our job then was just to make it happen. He was out in front of all of us.

Timothy Naftali, biographer: Germany loomed large in the history of postwar Europe, and arguably of the whole U.S.-Soviet competition. The Soviets felt that their share of Germany was a prize that they had won for beating Hitler. They also saw their slice of Germany as their front line, as a defense against future attacks. Bush saw that with care, he could get the Soviets to give up what had been their great prize. This is where Bush actually got ahead of most of the foreign policy analysts and most of the leaders in the free world.

Narrator: The Soviets had built the wall dividing Berlin in 1961 to keep the East Germans from fleeing. In early November 1989 Gorbachev prodded East Germany's leader to open its borders to "avoid an explosion." Within days, the Berlin Wall, the very symbol of the Cold War, was breeched.

George H. W. Bush (archival): Well, I don't think any single event is the end to what you might call the Iron Curtain, but clearly this is a long way from the harsh days, the harshest Iron Curtain days -- a long way from that.

Reporter (archival): In what you just said, that this is a great victory. You don't seem elated.

George H. W. Bush (archival): I am elated. I'm not a very emotional kind of guy.

Richard Norton Smith, presidential historian: He famously said that his mother told him as a boy not to indulge in braggadocio. And if there was ever a time when any other American president would have been tempted to indulge in braggadocio, it was 1898-1990, the end of the Cold War, the great victory of the West over the Marxist experiment, over the "evil empire."

Narrator: The wall had inspired some of the most memorable post-war presidential rhetoric.

John F. Kennedy: And therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words, Ich bin ein Berliner.

Ronald Reagan: Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.

Richard Norton Smith, presidential historian: Any other president would have gotten in a plane and flown to Berlin, and beat his breast, and engaged in "I told you so" triumphalism. And Bush not only didn't need to do that, he had the strength of character to resist everyone around him who told him that that's what he should do as President of the United States and leader of the free world.