Narrator: One by one, Hollywood’s biggest stars and movie moguls paraded into a huge tent. Clark Gable was dressed as a cowboy. Henry Fonda and his wife wore clown outfits. Cary Grant showed up as a trapeze artist. As they crossed a special gangway, a burst of air puffed up the ladies’ skirts.

A full-sized carousel, imported from the Warner Studios lot, swept the revelers in circles. Presiding over the festivities, in a ringmaster’s gaudy outfit, was the newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst. He had thrown the party in April of 1937, to celebrate his 74th birthday, at the Santa Monica mansion of his mistress, the film star Marion Davies. The theme of the evening was “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

It was a fitting tribute to Hearst, whose career had often resembled a three-ring circus. By the strength of his personality and a seemingly endless reservoir of money from his family’s fortune, he had become America’s most powerful and controversial media tycoon.

David Nasaw, Author, The Chief: We live in a world that’s dominated by media. It’s with us when we wake up in the morning, when we have our lunch, when we go to bed at night. It’s the air we breathe.

Andie Tucher, Historian: He made journalism really important whether or not you believed that he was doing good journalism. He made the act of publishing news and intelligence and opinion and sensation, he made that act really important.

Greg Young, Writer: I think in almost every form of media today you can see traces of this Hearst ideology: the flamboyance, the fearlessness, the sort of pushing right to the edge in a way to make these direct contacts with the American people.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: He brought narrative, he brought melodrama, he brought variety. The marketing, the hype, the sensationalism. But I think at the same time the lack of concern with objective truth, the out and out lies, the out and out fabrications, the out and out distortions were pernicious. And we’ve seen them having effects on journalism even today.

New York City, 1885

Narrator: William Randolph Hearst, at age 22, was just another rich kid, one of a hundred aspiring tycoons in New York City, all hoping to blaze their name in history.

He was a senior at Harvard College, and was yet again on the brink of expulsion. He’d been sent down by his parents to cram for his looming final exams.

But when, exactly, was Will Hearst supposed to study?

At night, a newly electrified Broadway called out to him with endless shows and performances. He loved the theater. Adored chorus girls. And knew all the steps to the Vaudeville shuffle.

Then, in the morning, there were the newspapers.

There was something for every taste and appetite. Papers that cost only a penny or two, catering to the city’s one point five million souls. Every single edition hand set on rotary presses, dashing off 24,000 copies an hour.

Greg Young, Writer: This was really an absolute golden age for newspapers. The greatest concentration of New York publishers were on one street called Publishers Row or Newspaper Row and it was right across the street from City Hall. It would have been one of the busiest places in the city, the smell of ink, the smell of newsprint, horse cars and newsies coming to pick up their newspapers to go deliver them.

Andie Tucher, Historian: Newspapers would come out throughout the day. They would be the 10:00 o’clock edition and then something else at noon and something else at 2:00. So the presses were always going. The staffs were always working. Sitting atop this industry, this vast effort to present news to the American people, put the publisher in a very powerful position.You could shape the opinions and the interests and the desires of your readers. You were a name people knew.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: Newspaper publishers and editors are truly kings among men. There was no other communicative mass media. So editors, in effect, strode the earth like colossi.

Narrator: The newspaper game was irresistible to Hearst. Young as he was, he already knew he wanted to be a player. He’d told his mother that he was searching for something. “Something,” he wrote, “where I could make a name.”

In fact, he was already somewhat notorious. In the three years he’d been at Harvard, everyone on campus had definitely heard of Will Hearst.

Victoria Kastner, Writer: Will Hearst was a phenomenon. He had an alligator that he took on a leash into class with him, named ‘Champagne Charlie’ because it was a beverage that the alligator liked.

David Nasaw, Author: He had an entourage that came with him. He had a full time valet at Harvard. He had a huge allowance. He had not a dorm room, but apartments and enough money to entertain all his undergraduates.

Narrator: Hearst was great fun. Though he stopped drinking in his junior year, he was a spectacular host and any excuse was a good one for a wild party. Classmates described him as “a mixture of boyishness and devilishness,” and elected him to all the most exclusive frats and elite societies. He’d once released hundreds of roosters into Harvard Yard. Then had commissioned several professors’ portraits -- on chamberpots. Hearst even took to the stage as a member of the Hasty Pudding theater club.

Victoria Kastner, Writer: Will Hearst was very bright. But he was not particularly interested in showing up regularly to class. What really made him passionate was when he became the business editor of the Harvard Lampoon.

Narrator: The Harvard Lampoon, was the college humor magazine with the reputation of being “always late and not always funny.”

Victoria Kastner, Writer: The business editor was the job that they always gave to the richest boy on campus because it always bled money. It was expected that he would be subsidizing the Lampoon but actually, he made it a success financially. He sold ads and that was the beginning, you know, his first whiff of newsprint.

Narrator: He’d secured the support of Boston’s finest tailors, jewelers -- and even carriage makers. In just two years, he increased circulation by 50 percent, advertising revenue by 300 percent, and soon he had the magazine out of debt and turning a profit.

By the fall of his senior year, he knew exactly what he wanted to do, and he couldn’t wait to get started.

“I am a man of business now,” he wrote home. “[And] I am convinced I could run a newspaper successfully. … [I want] to go to work.”

“Stand in like a man and stick to [your] studies to the end,” came his father’s reply.

All it took to pass the final exams was a grade of 50 percent, but Hearst never returned to campus. And he was expelled for good.

The Hearsts

Narrator: Far out on the high western plains, alone on that unending prairie, Butte, Montana, could not have made a starker contrast with New York City. In no way at all, did this dusty little town fit in with Will’s plans.

But immediately after his expulsion, his father decided it was time for him to join the family business.

Will was the only son of the mining entrepreneur George Hearst, whose empire included a half dozen silver, gold, and copper mines across the American West.

Will hated it from the start.

“Pa, this is the damnedest hole I have ever struck,” he wrote home. “And I am sure the four walls of a prison could not present any greater or more melancholy monotony than one obtains from this mine.” Will minced no words rejecting the world that for decades had been the source of the family’s vast fortune and that meant everything to his father.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: George Hearst is this rough and tumble guy who comes out from Missouri. He was an innate geologist. He was an untrained, untutored, natural geologist.

Narrator: When gold was found in California back in 1849, he’d hurried West to be part of it.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: The gold rush upended everything. It was as if somebody had picked up the entire country and tilted it to the west. People flooded in for this incredible bonanza.

Narrator: The promise of great riches drew so many from around the country and around the world, that the population of California increased three hundred times over. Most of these new arrivals never really had a shot.

Many of them were Chinese immigrants. If they wanted to try their luck, the state slapped them with an exorbitant monthly tax, and they faced violence in the mining camps.

But George Hearst thrived in that world. He was a white man from a wealthy family, who knew the right lawyers, and carried a big gun. For him plenty of venture capital was available to start new mines. And he soon struck it rich with a vast silver cache right on the Nevada border.

He returned to Missouri a millionaire, and met Phoebe Apperson, a brown-haired teacher 22 years his junior.

David Nasaw, Author: Phoebe was this demure school teacher who went to church, minded her manners, and George comes into town as this semi-literate scoundrel who cultivated the appearance of a rough hewn western miner.

Alexandra Nickliss, Historian: As a woman in the 19th century, practically the only way she could get out to California was to make the right decision to marry the right suitor. George was ambitious to succeed, he was looking for a sophisticated and cultured woman who could give him a son and an heir.

Narrator: William Randolph Hearst was born ten months after George and Phoebe married, in San Francisco, April 29th, 1863. George stayed in town only long enough to see the baby born, then he packed up and left for mining country, leaving his young wife to raise their son alone.

Alexandra Nickliss, Historian: This was a tough time for Phoebe. Early on in her marriage, she was disillusioned, frustrated, terribly lonely.

Narrator: She started to travel when Will was still a baby, leaving him with a nurse when she ventured, for months at a time, to the Yosemite valley, to Idaho, and even as far as Hawaii.

When she was home, her son would cling to her. Phoebe wrote to a friend that “he … seems to be afraid all the time that I will go away and leave him again.”

Whenever they were together, she indulged her young son.

David Nasaw, Author: Phoebe is the most important person in his life. As a child he can do no wrong. She excuses his failures. And he’s told from the beginning he can do whatever he wants to do.

Narrator: Phoebe liked to say that “[Will’s] forte [is] an irrepressible imagination.”

Once, to keep her from going to a party, her three-year old son poured castor oil all over her favorite dress.

A few years later, he set off fireworks in his room. As smoke filled the house, Will screamed FIRE, then locked his bedroom door and waited to see what would happen.

His dangerous prank was barely acknowledged.

In 1873, Phoebe set off on an 18-month tour of Europe and Will was finally invited to come along. Mother and son crisscrossed the continent, from England to Germany to Holland. They spent mornings studying languages together; afternoons in each other’s company at galleries and churches and museums. Ten-year-old Will was his mother’s date to every dinner, and even accompanied her to a meeting with the Pope.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: Phoebe was very, very close to her only son, Willie, and probably projected a lot of emotional intimacy and closeness onto him that perhaps she didn’t always have with her husband.

David Nasaw, Author: Will grew up in this bizarre, unstable environment where he rarely saw his father. The most troubling part of that childhood was the unstable finances. George Hearst spent his money as fast as he could. He had racing stables, he kept buying property, he kept investing the money he made in one mine in another mine.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: He had meteoric ups and downs, and the downs at times were pretty low. I think Will was too young to realize the real sense of, “Oh my God, the whole thing could collapse.”

Narrator: By the time Will was in his teens, George’s fortunes had stabilized, and the Hearsts had become one of the richest families in the country. George had grown his empire across the West and Central America -- from Utah, Nevada, South Dakota, and Montana, to Mexico. There was now plenty of excess capital in the Hearst accounts -- and some of it, George had earmarked for a new interest.

David Nasaw, Author: George Hearst, like many other mega millionaires in California, decides that the best way to spend his money is to run for office. And if you’re gonna run for office around the 1880s, the only way to get your name before the public is to own your own newspaper. So it makes perfect sense for him to buy The Examiner in San Francisco. There would be a story every day about what George Hearst did, thought and why George Hearst was an upstanding California citizen.

Narrator: By the spring of 1886, George had been sworn in as the democratic senator from California. Meanwhile, his 23-year-old son -- the college dropout -- was still loafing around the West.

Will had steadfastly refused to show any interest in the family’s mining business, but had managed to have the family’s paper delivered to every dusty mining town he dropped in on. His letters to his father were full of advice about how best to remake what he affectionately called “our miserable little sheet.”

“Now if you could make over to me the Examiner -- with enough money to carry out my schemes -- I’ll tell you what I’d do,” he wrote. “[I’d make] the paper as far as possible original.”

Gary Kamiya, Writer: The dude was a born newspaperman. One of the most impressive things about Hearst is how this undisciplined, spoiled brat, kind of rich kid who has been traipsing around the west, once he discovers his calling, he zones in on it. So to some degree, he went into newspapering because I think he realized this is what I’m good at.

Narrator: In the face of his son’s stubborn certainty, George relented.

“There’s one thing sure about my boy,” he’d once remarked. “When he wants cake, he wants cake … And … after a while he gets his cake.”

Startup

Victoria Kastner, Writer: When Will took over the San Francisco Examiner, in March of 1887, when he was all of 24, it was a second rate money-losing headache of a newspaper, but he christened it ‘the monarch of the dailies’ and proceeded to start stirring things up.

Narrator: It took all of 13 days for the young newspaperman to be arrested for libel. His paper accused some supposedly crooked lawyer of taking advantage of the good people of San Francisco.

Hearst was in prison just long enough to snag a few national headlines. Boy was it good to finally be a part of the game.

Will Hearst’s main competition in the city came from the Chronicle, and from the Call -- respectable papers with swanky headquarters designed by leading architects. The offices of the San Francisco Examiner, meanwhile, occupied a squat building on Sacramento Street. It didn’t look much like the launching place for a revolution.

But Hearst arrived with several writers from the Harvard Lampoon and then hired on the very best news people he could find -- no matter their price.

“Dear Papa, … I have been … trying to find a managing editor. … We may be able to get Ballard Smith [of the New York Herald]. The paper requires a head that has ability and experience. … Naturally such a man commands a high salary and you must reconcile yourself, either to paying it or giving up the paper.”

Gary Kamiya, Writer: Hearst realized I can actually make this thing a success especially if I have basically an unlimited spigot of money.

Narrator: New hire Winifred Black, a 24-year-old midwesterner, claimed that “nowhere was there ever a more brilliant or more outrageous, incredible, ridiculous, glorious set of typical newspaper people than there was in that shabby old office.”

Victoria Kastner, Writer: Hearst believed that life should be fun, and that meant work should be fun.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: He was in many ways a great boss to work with. This madcap exuberance of these mostly young men who were just getting paid a lot of money, they were drinking themselves crazy. You know one editor would say “Can we fire this guy he’s completely drunk” and Hearst would go “Well as long as he’s sober one day in thirty that’s good enough for me.” So he had a very latitudinous attitude towards vice. He didn’t care about that as long as they delivered the goods.

Narrator: The young publisher seemed to fill the newsroom with sheer personality. He was a big man, over 6 feet tall, with a high-pitched voice and piercing blue-gray eyes.

David Nasaw, Author: Hearst rules with a smile. He doesn’t yell at anybody, he doesn’t fire anybody, but he wants things done his way. This is my newspaper.

Narrator: Will liked to say,“[I am making] a newspaper to suit me.”

He wrote many of the headlines himself -- and reviewed all the copy. His name might only appear on the masthead, but his hand was there on every single page.

Greg Young, Writer: I think in a way, Hearst was ahead of his time. Previously, newspapers were dull as dishwater. There were almost no illustrations and there were certainly no photographs back then. It was just lines of text and for the most part every newspaper looks like the one from the day before.

Jeet Heer, Writer: Hearst totally changed the nature of the newspaper. The news had to have personality, it had to have character, it could not be dry or simply factual. For Hearst, journalism was like boxing. The rambunctiousness, the vibrancy, it’s bloody, it might do damage to your brain, but still you make people root for you and you change how they think.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: It had to be punchy, hyperbolic rhetoric, really lurid adjectives. It’s almost hard to describe it because these techniques have become so engrained in media.

Narrator: Soon, The Examiner had a new slogan that reflected Hearst’s obsession: “THERE IS NO SUBSTITUTE FOR CIRCULATION.”

Stephen Hearst, Great-Grandson: He was always thinking about what he could do to attract eyeballs. His business was about eyeballs. And how many people I can communicate with in a day. He went after the last grizzly bear in California. His editors had chased this bear for weeks and weeks and there were updates in the daily paper in the Sunday paper would have a larger update, so you’d have to read Monday through Saturday and then he’d capsulize it in a major story on Sunday to build readership.

Narrator: Finally caught in late October 1889, 20,000 people a day came to gawk at Hearst’s big new creature, which he named Monarch, after his paper.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: He was always doing these kinds of stunts. It was just naked self promotion. And in fact the nakedness of it was almost part of its appeal, it was so blatant, it was so ridiculous that it became kind of addictive in that way too. There was no attempt to be tasteful. No, taste was, like, for losers.

Narrator: On his 27th birthday -- after three years at the helm -- he had grown his circulation from a measly 5,000 to well over 55,000, and the young publisher watched those numbers more closely than anyone.

He had an intuitive understanding of the kind of reporting that sold his papers -- it was all about tapping into his readers’ emotions. All the better if their passions lined up with his politics.

Like his father, Will was a staunch democrat, at a time when white supremacy was one of the party’s core principles. In college, he’d performed in blackface with his white friends. In every way, The Examiner was Will Hearst’s platform, and his openly racist sentiments would find a place of prominence in its pages.Erik Loomis, Historian: He is supportive of a white man’s America. And anyone threatening that, be they black, be they Asian, be they Native, be they Mexican, is somebody who has to be either eliminated or suppressed.

Narrator: Now, in 1890, eight years after the passage of a federal ban on immigration called the Chinese Exclusion Act, Hearst aggressively took up against Asian people in California.

David Nasaw, Author: When Will Hearst takes over The Examiner, San Francisco is the center of an anti-Chinese, anti-Asian racism that is frightening. White people were convinced that the Chinese are taking away jobs.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: There was definitely rioting, there were acts of violence. Hearst and The Examiner fanned the flames of racial discontent really expertly. It’s visceral. It appeals to people’s fears, to their base, their emotions. And he also, I’m sure, sincerely believed it.

Narrator: In a signed editorial, Hearst would write, “I am strongly in favor of … exclusion, to prevent these Orientals swarming the country and absolutely overwhelming it. … We want our country not merely for the white race, but for ... [our own] standards of wages, standards of living. This is not race prejudice. It is race preservation.”

These sentiments would go on to become one of the mainstays of his entire journalistic career, deployed whenever it suited him, to galvanize his readers’ fears. The way Will Hearst saw it, more readers meant more followers meant more power.

Succession

Narrator: As Hearst’s readership and influence grew, so too did his appetites. He had commissioned the building of a boat, the Vamoose, designed to be the fastest steamship in the world, and every morning the young publisher could be seen racing across the Bay to San Francisco, from his new home in the village of Sausalito.

Andie Tucher, Historian: He wanted above all to be noticed, to be important, to be on top. He wanted people to pay attention. He was hyper-competitive--he wanted to be the richest one around as well as the most powerful one around.

David Nasaw, Author: Hearst wants to get all the attention. He wears the loudest plaid suits with yellow ties. And he takes great joy in thumbing his nose at respectable society.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: He could have lived where his parents lived, the big tony San Francisco neighborhood Van Ness, but instead he moved to Sausalito. Up on the cliffs, it's a magnificent house that he bought overlooking the Bay. It's a little off-beat thing for this very hedonistic, willful, self-willed man who kind of did what he wanted to do. He was definitely a maverick in that way.

Narrator: Hearst’s sprawling bachelor pad had plenty of room for lavish full of firecrackers, games, and beautiful women.

Victoria Kastner, Writer: He wanted entertainment. He wanted to be around people who were fun and who were talented. And he especially loved show girls, that was for sure.

Narrator: Once, he’d seen the British actress Adelaide Neilson onstage, and even though she was 15 years his senior, he’d been completely smitten.

Then there’d been Lillian Russell, at the time the highest paid actress in the country. He said his feelings for her had been so “tense, dramatic, and ecstatic,” that he’d wanted to propose.

Soprano Sybil Sanderson, he had proposed to -- but Phoebe had quickly intervened.

And who could forget Eleanor Calhoun, yet another Will Hearst fiancée? To Phoebe, the young actress was a gold-digger and a “devil fish” -- and was soon gotten rid of as well.

Will now lived openly with a waitress from his Harvard days named Tessie Powers.

Victoria Kastner, Writer: They were together for 10 years and he took her everywhere. They traveled together. They went to the opera together. He was extremely proud to be with her and she loved him.

Narrator: But she had the same problem as all his other girlfriends.

Victoria Kastner, Writer: Tessie definitely did not have the kind of social background that Will’s mother, Phoebe, wanted her to have. Phoebe didn’t think that it was inappropriate for her to break up his romances and she didn’t think it was inappropriate for her to regulate his expenditures.

Narrator: For Phoebe, it was all connected to preserving the family’s wealth and reputation.

She wrote to George: “[You must convince] Will to change his manner of living. … How is it possible for him to devote his time and attention to a prostitute and utterly ignore his mother?”

David Nasaw, Author: She loved her son but she feared that her son was too much like his father. A wild-eyed alcoholic, and a crazy spendthrift.

Narrator: “Will has been spending an enormous amount of money, more than you and me together. … Do you intend to continue your indulgence? … If you have any courage, it might be well to say a few words to Will.”

Victoria Kastner, Writer: George was an indulgent parent but I wouldn’t say he was particularly involved. He let WR you know, run the presses and do kind of whatever he wanted. He was more a parent from a distance.

Narrator: Despite Phoebe’s many attempts to rein in her son, Will was stubborn.

“You have often asked me what I could do with my money and that I must squander it on the girl. But a fellow does like to live a little.”

Will had already spent the equivalent of 3.7 million of today’s dollars on the Examiner -- as well as almost a million more on himself. And he still wasn’t satisfied. In four years, he had topped the San Francisco market without much of a fight. Now, he was getting bored, and longed to test himself -- and his bold brand of journalism -- against much bigger foes.

All he needed was for his father to support this new venture. But things were different this year. As his son well knew, George was very ill.

On February 28th, 1891, George Hearst died.

“He was the best judge of a mine in this or perhaps in any part of the world,” stated The Examiner. “In which work he has had no rival.”

Victoria Kastner, Writer : I think he admired George very much. He admired his independence. He admired the fact that acquiring all of that wealth, becoming a senator, didn’t change him a single bit. When George Hearst died, he left a will that the New York Times estimated at between 15 and 20 million dollars, and that is in 1891.

Narrator: Today, George’s fortune would be equivalent to half a billion dollars. And, as the only son, Will was expected to inherit it all.

But the inheritance, when it was announced, held a nasty surprise for the young publisher. His mother, Phoebe, had gotten everything.

Victoria Kastner, Writer: In the will, George said that Phoebe should be sure to provide for their son. But Will was 28 at the time and certainly crushed that his father didn't make him a part of the inheritance in a more specific way.

Narrator: Now a grieving widow, Phoebe Hearst -- long Will’s closest confidant -- had just become something else entirely to her son.

“You have always been most kind and generous to me and given me extra money whenever I asked for it,” he wrote, “but don’t you think it would be better for me if I didn’t ask for it so often, if I were put now on a more independent and manly footing?”

Victoria Kastner, Writer: It put him in this very awkward position. He had to go to her, you know, palm extended, hat in hand, and ask for funds, which was a very difficult thing for him to do, and I think it was hard on their relationship as well.

Narrator: Will had no property or income of his own. He desperately wanted to move to New York and buy another paper -- but he could only do so with a huge loan from his mother. He knew that she’d never agree if he was still with Tessie.

Alexandra Nickliss, Historian: Once she received control of the entire Hearst estate, she became one of the wealthiest women in the United States. And she grew into a very demanding, imperious individual. She expected people to do what she wanted.

Narrator: Will Hearst had been given so very much, yet so much was now off limits. He understood his mother’s price, and he split with Tessie for good.

The Dragon

New York City, 1895

Narrator: Snubbed by his dead father and reeling from his split with Tessie, Hearst arrived in New York a man on a mission.

The city couldn’t fail to improve his mood -- everywhere he looked, daring new projects were going up; the shape of the skyline changing by the day.

Greg Young, Writer: New York is one of the most exciting places to be in the world in the 1890s. It is a city with so much wealth in it. There’s so much happening in New York.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: New York was the big tamale, the big enchilada. It was the biggest population, it was where the big newspapers were. There was a sense that if you could make it there, you could make it anywhere.

Narrator: Phoebe had armed her boy with letters of introduction that would have opened any door into the respectable world of the New York elite. But after calling on one or two of his mother’s friends, Hearst yet again made it clear that he preferred to go his own way.

Greg Young, Writer: New York City has one of the most impenetrable like social upper crusts. You’re talking very old families who have acquired a lot of wealth and a lot of social privilege. On the other hand, Hearst doesn’t like to follow rules. He’s also a little bit of a disruptor.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: Hearst liked that sense of flaunting propriety, but at the same time he always wanted to be at the top of the social heap. It’s classic Hearst. There's this quality of I may be a wild man from the West, but I have a lot more money than you.

David Nasaw, Author: If he had put all his effort into it, he could have become a respected gentleman, but he doesn’t want to, he’s got better things to do.

Narrator: The publishing industry had changed since Hearst had last been in New York in his student days. Papers were being churned out faster than ever before -- a revolution fueled by the linotype printing press, a steam-powered monster so loud that many printers were now hired from among the city’s deaf population.

David Nasaw, Author: The New York market in newspapers was overstocked. There were dozens of newspapers that were doing very, very well.

Narrator: Hearst surveyed them all with an expert eye, peering into every corner of the market.

Niche publications -- like the Wall Street Journal, specialized in business news and catered to the street’s brokers and financiers. The erudite New York Tribune was much beloved by the literary set. While the Yidishes Tageblatt -- the “Jewish Daily News” -- printed for conservative and orthodox leaders. The New York Age, and The Woman’s Era were created for, and by, the Black community.

No fewer than twenty papers appeared in languages other than English. The New York Times became known as the gray lady, because of its staid layout and establishment politics. Its circulation paled in comparison to the Sun, which had as many as 100,000 subscribers -- and to the Herald, which drew 200,000 a day.

But at the top of the pack was the World, printing a quarter million copies weekday mornings and over 500 thousand on Sundays. Owned and operated by Joseph Pulitzer, The World was the single most popular newspaper of the age, and Hearst wanted nothing more than to take it down.

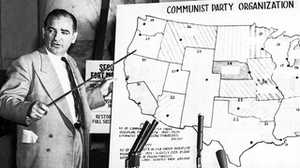

Gary Kamiya, Writer: So the dragon is Joseph Pulitzer. This is who Hearst wants to beat if he is going to become the undisputed heavyweight champion of the journalistic world. He’s got to knock out Joe Pulitzer.

Narrator: Pulitzer -- at 48 years of age to Hearst’s 32 -- had everything the younger man wanted. He had risen from nothing to become the 24th richest man in the country.

He employed the biggest news staff on the planet and shaped the opinions of millions. A democrat, like Hearst, he’d tried his hand at politics and been elected to Congress.

His success had brought him a string of waterfront properties. He had several boats all much bigger than Hearst’s. And everything he’d achieved, he’d fought for, and won.

Greg Young, Writer: Joseph Pulitzer was an immigrant who made it big in St. Louis and owned a newspaper there. In the 1880s, he came to New York and he was kind of the big shot. He really changed the nature of journalism. Hearst actually modeled his own newspaper out in San Francisco on what Pulitzer was doing.

Andie Tucher, Historian: The New York World was so visible, it was such a presence in the city. It was hard to avoid reading Pulitzer's paper. This was a newspaper that was really focused on the needs and the interests of the enormous immigrant population in New York City.

Narrator: Never before in American history had there been more immigrants arriving on its shores.

Robert Chiles, Historian: New York is an immigrant city. It's overwhelmingly Irish immigrants as well as a lot of German immigrants. And those people keep coming. But now, in the late 19th century, you suddenly have this surge of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. And so you have the arrival of Italian immigrants, by the tens and hundreds of thousands. Jewish immigrants from the Russian empire. It was a vibrant and diverse population in this city. And they were living in crowded conditions and they were, by and large at the bottom of the city's economy.

Jeet Heer, Writer: There’s two different models for how you can make money for newspapers. There's the New York Times model where you don’t get the most readers, but you get upscale readers and you have a genteel, respectable newspaper that appeals to them and you get advertising. And there’s the Pulitzer model where you get the most readers that you possibly can, including, you know, the poor, the immigrants, the working class. Like trying to reach the masses.

Narrator: As Hearst saw it, the working people of New York City were the prize and Pulitzer was standing in his way.

After weeks of shopping around, Hearst finally settled on the vehicle for his plans -- a little 2-cent paper called the Morning Journal. He tapped the equivalent of 4.7 million dollars from Phoebe’s estate, for a paper with only 70,000 readers.

Andie Tucher, Historian: The Journal, when Hearst got hold of it, was not at all important. It was not at all interesting, nobody cared, nobody bought it. It was a good thing to get if you wanted a cheap way to enter the New York market, but other than that, it was not gonna bring any loyal readers with him.

David Nasaw, Author: Everybody thought wow you know this young kid he may have made it in San Francisco but he’s certainly not going to succeed in New York and he’s certainly not going to succeed by buying the Journal!

Narrator: A cartoonist working over at the World remembered that, “[Hearst] was both pitied and jeered when it leaked out that he had bought the Journal. … [He was] ridiculed for his youth and assurance, … [and] sneered at as a rich man’s son.”

David Nasaw, Author: Hearst knows that he’s got to spend a lot of money. He then goes on a shopping spree. He buys the best editors. He buys the best newspaper men. And he gets most of them from Pulitzer.

Narrator: He hired away Morrill Goddard, a star reporter and editor. When Pulitzer replaced Goddard, Hearst hired away the new editor, Arthur Brisbane, as well.

Not to be outdone, Pulitzer often bested Hearst’s offers. Entire staffs switched papers one day to the next. Media critics dubbed Hearst a “monopolist of talent.” Rumor was, he’d even lured away Pulitzer’s pressroom cat.

The rivalry rippled across every section of their papers. Hearst soon debuted the American Humorist, an enormous, Sunday comic supplement as tall as a large toddler.

Erik Loomis, Historian: In the late 19th century, comics are tremendously successful, enormously powerful. It gives a 12-year-old a reason to buy the paper.

Andie Tucher, Historian: Comics expressed things dramatically often because readers were perhaps recent immigrants, working class people, people for whom English was not a strong language.

Greg Young, Writer: Over at The World, Pulitzer had an illustrator named Richard Outcault and Outcault, created a little character that was called The Yellow Kid. A sickly little boy in like a yellow robe.

Jeet Heer, Writer: The Yellow Kid was a slum kid. Why is he bald? Because kids who have lice, they get their heads shaved -- especially young poor kids.

Narrator: Outcault explained that: “The Yellow Kid was not an individual, but a type. When I used to go about the slums on newspaper assignments I would encounter him often, wandering out of doorways or sitting down on dirty doorsteps. I always loved the Kid. He had a sweet character and a sunny disposition, and was generous to a fault.”

Greg Young, Writer : Hearst, of course, steals Outcault away from Pulitzer, however Pulitzer then just hires another illustrator to make a Yellow Kid.

Jeet Heer, Writer: So there are two rival Yellow Kids. There’s a Pulitzer Yellow Kid and a Hearst Yellow Kid. People want papers that convey the reality of slum life, convey the reality of living in a tenement, of poverty, of hunger. That bald kid really resonated with the public. And Hearst being Hearst, he found that was also very profitable.

Narrator: Now that Hearst had the cartoonists, the writers, and all the editors he’d wanted, he set in motion his most devious plan yet. He went ahead and dropped the price of the Journal from two cents to one. Newspapers that sold for a penny, Hearst claimed, were the “true” tribunes of the people.

Robert Chiles, Historian: He sells his newspaper for half the price of Pulitzer’s newspaper and Hearst can do that because he has a lot of money and he can afford to lose money for a while.

Narrator: In just three months, the Journal’s circulation more than doubled, jumping from 70,000 to 150,000. No longer able to ignore the Journal’s success, Pulitzer dropped his price as well. The editorial in the paper announcing the price change was succinct: “We prefer power to profits.” Privately, Pulitzer told his editors, “We must smash the interloper.”

At a penny apiece, both papers got the eyeballs they wanted -- but now lost money on every copy. A great game of high stakes chicken had begun.

The Villains

Erik Loomis, Historian: Being a worker at this time was a life of poverty, of desperation, living in massive crowded tenements. People worked fourteen-sixteen hour days, they had no right to a union, workplace safety was abysmal. There are very few wins for workers during these years. So there’s more and more tensions in America over the issue of class.

Andie Tucher, Historian: It was an era when there was a real call for reform. The end of the 19th century was a heartless, monopolistic, capitalist, gilded age.

Jeet Heer, Writer: You had the first billionaires and the first giant corporations that owned everything. They had vast monopoly power.

Narrator: These corrupt, sprawling monopolies were known as the trusts, and every day necessities like coal, sugar and coffee all fell under their purview. Charles “the Ice King” Morse, for example, controlled all 285 million tons of ice the city used every year -- ice for homes, restaurants, and even morgues.

There were few incentives to set fair prices, or to treat workers well.

David Nasaw, Author: When Hearst gets to New York, I think he’s outraged at the corruption. The working people of New York, largely immigrants, are being ripped off right and left. That corruption is rampant, that the Democratic Party while pretending to represent the immigrant working class is making it more expensive for them to get clean water, to get sewers, to get gas, public schools, milk and everything else. And he knows that this is a way to win circulation and to, you know, gain power for himself.

Narrator: Back in San Francisco, Hearst had made a name for himself by taking on the Southern Pacific Railroad, one of the biggest trusts in all the West.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: The Southern Pacific Railroad, it’s hard to grasp how powerful it was. It essentially ran the state. It was said that the government of California was not in Sacramento, it was at 4th and Townsend street, which was where the SB headquarters were. They bought off politicians. They gave subsidies to newspapers for favorable coverage. They were omnipotent and they were always hated by large numbers of San Franciscans. Hearst sent his best man, Ambrose Bierce, and he basically siced him on the almighty Southern Pacific railroad. And Hearst when he decided he wanted to go after something or someone he was dogged and ruthless and unswerving. And he loved victory. So it was both a good crusade -- it was good on the face of it, and it was also good for business.

Narrator: Now, in 1896, Hearst took what he’d learned in San Francisco, and mobilized his staff at The Journal to wage war against all New York City trusts.

Erik Loomis, Historian: The Journal was able to channel stories about the struggles of workers in ways that gains them political sympathy and that promotes the idea that maybe the state should fix some of these problems. And that is critical right? For the first time, a major paper is saying the state needs to fix some problems.

Narrator: When the Gas Trust wanted to tear up vast reaches of the city’s streets to lay unnecessary new gas mains, Hearst had his best lawyers argue against it, taking their case all the way to the Supreme Court. Then when the American Ice Company more than doubled its prices -- putting ice out of reach for most New Yorkers -- The Journal took down the Ice King, smashed the trust, and in the process exposed a sprawling corruption scheme that ended the mayor’s political career.

Hearst’s readers loved it, and every morning brought letters of appreciation from across the region.

“The multitudes” Hearst wrote in an editorial, “are individually helpless against the rapacity of the few.” But, with The Journal on their side, the people “could be armed against their despoilers.”

Jeet Heer, Writer: For Hearst, journalism was getting the reader engaged. The whole point of news is to create stories that the reader can be drawn into.

Chenjerai Kumanyika, Media Scholar: They’re tapping into a kind of anger, right? And the anger is a motivating force, that motivates people to read, motivates people to get involved with stories. Even if those stories are being rendered in a lurid and kind of you know sensational way, they’re about ordinary people and expressing an outrage, with a kind of authenticity that maybe you’re not seeing in some of the more elite papers. So, if you’re reading this stuff that’s very compelling and you know you probably feel like he’s your champion.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: There was this crusading and idealistic aspect that was fresh. It was the narrative, it was the melodrama, it was the marketing, the splashiness that he brought that made it effective and made people want to read it. And that he was fighting for important issues. You can’t dismiss that this advocacy journalism in its rawest form paid very positive dividends in terms of ending this very corrupt system.

Narrator: Hearst called what he was doing “the new journalism” and ranked it above even the city’s courts as a force for justice. The young publisher was riding high, energized by each new crusade -- and loving absolutely everything the city had to offer.

Scandalous Mr. Hearst

Greg Young, Writer: If you wanted to have a good time in New York around the turn of the century, you headed to the Tenderloin. You could find the best dance halls, the seediest saloons, the brothels, and the gambling dens. Normally men like Hearst would not be seen in the Tenderloin. Of course, it would damage their social status. But Hearst really wasn’t that kind of a guy, and he enjoyed meeting dancing girls.

Narrator: Ever since he’d arrived in New York, Hearst had been seen with one performer in particular. Her name was Millicent Willson.

Victoria Kastner, Writer : She and her sister Anita were the dancing Willson sisters. They did something quite daring in vaudeville, which was they rode bicycles across the stage. They were bicycle girls.

Narrator: The sisters performed in musical comedies in which they showed as much leg as they could without getting arrested.

Millicent was 16 when they met, and Hearst was nearly twice her age.

“When he asked me to go out with him … my mother was against it,” Millicent explained. “I recall she said, ‘Who is he? Some young fellow from out West somewhere … ?’ She insisted Anita had to come or I couldn’t go.”

Victoria Kastner, Writer: He walked around with both of them. One on each arm, which people thought was quite scandalous.

Narrator: The Willson sisters even joined Hearst on lavish vacations abroad.

Greg Young, Writer: He was doing things on the edge of respectability. In both his personal and professional lives he thrived and enjoyed pushing things to the limits.

Victoria Kastner, Writer: Hearst was a man of action. Millie would say that they wanted to go to Sherries or Delmonico’s and have some lovely meal. But instead he wanted to go down to the newspaper office and Millie and Anita would spend long boring hours as W.R, went over the masthead, changed the headline, corrected things for the last edition.

Narrator: Hearst developed a routine where he’d work all day, hit the theater with the Willson sisters, then return to the Journal -- with or without the girls in tow.

One of his editors later recalled that, “Hearst would come back at about 1:30 in the morning and [then would proceed] to rip my editorial pages to pieces. … It was always an interesting spectacle … to see this young millionaire, usually in irreproachable evening dress, working over the forms, changing a head here, shifting the position of an article there, clamoring always for more pictures and bigger type.”

Greg Young, Writer: In the first couple of years of the Journal, Hearst basically threw everything at the wall to see what would stick. Because of this, his newspaper was known as a place for exciting ideas and for interesting concepts because it was so much more interesting than everything else that was being sold at the time.

Narrator: By 1897, two years into his ownership of the Journal, Hearst’s rivalry with Pulitzer was pushing past all usual boundaries of decorum.

The Journal’s circulation climbed so steadily that Pulitzer became convinced that Hearst must have a spy in his newsroom, and even put in place a system of codenames to confuse the competition.

Hearst, meanwhile, seemed equally willing to publish tasteless exposés on his front page, to print titillating drawings in his theater reviews, and to degrade and dehumanize in his comics. Anything to sell his paper.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: There’s no question that Hearst was an expert at appealing to fear, to lust, to voyeurism, to sensationalism. And probably the most obvious aspect of this is crime. He was a master at creating heroes and villains so that whoever the murderer is, is a demonic, satanic figure, threatening everything that we hold dear. And the victim is like the damsel on the white horse. He increased the ratio of crime stories to an extraordinary degree, 20 or 30% of the stories in the journal were crime stories. And he was pretty shameless about it.

Narrator: In the summer of 1897, when a headless body washed up on the banks of the East River, both Hearst and Pulitzer were determined to make the most of it.

Andie Tucher, Historian: This was, of course, a case that had lots of potential for sensation. And both of them were covering it. But Hearst sets up what he calls his own murder squad, his own reporters who go out with the police, investigate with the police.

Narrator: Hearst dispatched twenty reporters to swarm the murder scene and the city morgue.

The case hinged on a distinctive red and yellow oilcloth that had been used to wrap the body, and Hearst’s team canvased every store in town, until they figured out exactly who had supplied the killer.

Andie Tucher, Historian: Now, bear in mind, Hearst has his people doing detective work that the detectives are not doing.

Narrator: Hearst’s bold coverage fit perfectly with the Journal’s new motto: “WHILE OTHERS TALK THE JOURNAL ACTS!”

Greg Young, Writer: This idea that reporters need to be in the story required a new type of journalist called the stunt journalist. It was a little mix of investigative journalism and a little bit of reality TV. They would do disguises, they would embed themselves into places all for the idea of finding a story that related to the working class person.

Chenjerai Kumanyika, Media Scholar: He understands you have to be in it. He wants his reporters to be along for the ride. And, you know, he would tell his reporters, visualize the news before you write it.

Narrator: When Hearst got a tip about the identity of the murderer, he jumped on a bicycle and raced uptown, outstripping even his own reporters.

In the end, it took all of three days for Hearst and his team to crack the case. Two Journal reporters made the first arrest, leaping into a moving carriage on 9th Avenue and catching the suspect in full flight.

Hearst loved every second. He’d always remember the way he’d closed that case. “We were young,” he’d write wistfully. “It was an adventure.”

Question was, once Hearst had raced through the streets in pursuit of a killer, was there anything he wouldn’t do?

The War

Havana, 1897

Gary Kamiya, Writer: Cuba was this last colonial possession of the Spanish empire. And it was a very controversial political situation there in which there was a Cuban rebellion against Spanish colonial rule.

Narrator: Back in 1895, revolutionaries calling for “independence or death” had risen against the Spanish. The rebels had been violently repressed, but their bloody struggle had continued for two years.

David Nasaw, Author: Hearst loves a good story and he loves a story that could be made into a melodrama. He sees a developing story in Cuba where the bad guys are the Spanish, the damsel in distress is the Cuban people, and the hero is going to be William Randolph Hearst and the American government that’s going to rescue these poor Cubans.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: The Hearst papers were vehemently pro Cuban rebels and they painted them as this noble band going up against this evil colonial empire and Hearst just played that to the max.

Narrator: Hearst believed that Europeans should stay well away from the Americas, and to get his point across, he was willing to publish almost anything -- especially now that he’d found a new villain that his readers loved to hate.

Greg Young, Writer: The tensions between Cuba and Spain at this time represents a story of independence that was very appealing to New Yorkers and to Americans overall. Hearst is beginning to formulate a plan that this is an event that we can actually be a part of in a way that no other newspaper is. He is sending correspondents down to Cuba that were sending these breathless updates, that were often highly exaggerated, but were unbelievably entertaining.

Narrator: Hearst published story after story from Cuba, each more sensational -- and less tethered to reality -- than the last.

He soon zeroed in on an 18-year-old revolutionary named Evangelina Cisneros, who’d been imprisoned without a trial. The Journal published wildly melodramatic articles about her plight, then Hearst had one of his reporters smuggle her out of Havana, disguised as a man and smoking a Cuban cigar. Cisneros arrived in New York a sensation.

Hearst paraded her around the city like his own personal war trophy -- hosting an elaborate dinner in her honor at Delmonico’s, a ball at the Waldorf, and a rally at Madison Square Garden that drew 75,000.

His frenzied coverage brought more and more readers to the Journal, and branded Spain as enemy number one.

Then, on February 15th, 1898, off the coast of Havana, a battleship called the USS Maine exploded. Two hundred and sixty-six American sailors were dead. Hearst was convinced that Spain was to blame, and was determined to seize the opportunity.

“Arouse everybody,” Hearst telegrammed his team. “Maine is [a] great thing.”

Gary Kamiya, Writer: This point is when he began, for the first time, cross these lines. What he did was so beyond the bounds of acceptable journalism by any standard.

David Nasaw, Author: Hearst, immediately publishes on his front pages a variety of stories, going after the Spanish, all made up.

Andie Tucher, Historian: The battleship Maine, was probably an accident. Everything suggests that it was probably an accident. But at that point, it was impossible to simmer everybody back down. So war seemed inevitable at that point. And Hearst loved it.

Narrator: Hearst was well aware that this was the biggest story of his career, and he intended to push it as far as he could. The Spaniards were not men but beasts, he claimed, and proceeded to spread outright lies about their troops savaging women, poisoning children, and feeding prisoners of war to sharks.

Pulitzer had recently jumped on the bandwagon as well, and the World was soon trafficking in reporting almost as sensational as Hearst’s.

Now, both Hearst and Pulitzer were demanding that the President declare war at once.

William McKinley, a moderate Republican who’d won the White House on a business-friendly ticket two years earlier, remained cautious. “War should never be entered upon until every agency of peace has failed,” the President maintained. But with every paper sold, the calls for war grew louder.

The unrelenting, over-the-top war-mongering Hearst and Pulitzer engaged in earned them a new nickname -- Yellow Kid journalists.

“Nothing … troubles the yellow journalist,” one critic complained. “His object is sordid and mercenary. His cry is for blood. The more of it the better.”

“Yellowdom’s strong point,” another stated, is “the total disregard for truth and dignity.”

Jeet Heer, Writer: The whole idea of the yellow press was that these are trash papers that publish gossip, publish scandal, and also are riling up the masses.

Andie Tucher, Historian: The spiral of sensationalism that Pulitzer and Hearst were drawn into, I think it made it a lot easier to cross lines that they might not have crossed without the heat of competition pushing them onward.

Narrator: Now The Journal was lambasting McKinley almost daily, denouncing him as weak and indecisive. Finally, on April 20, 1898, McKinley asked for a declaration of war. Hearst was more than happy to take the credit.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: The hutzpah of this is so unbelievable. “How do you like The Journal’s war?” So he just nakedly, unabashedly, unapologetically takes credit for this war.

Narrator: At night, the publisher celebrated by launching rockets from the roof of his headquarters in New York and San Francisco. “Watch the skies,” he told his readers. “If you see the bombs it means that war is on.”

Andie Tucher, Historian: Hearst was someone who wanted more than anything else to be on top and to win. He was somebody who cared deeply about having influence and being a big man on the world stage.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: He wants to rule the world, he wants to have more power, more influence, more money, more everything than everybody. In the Spanish American war there’s a playfulness to it, which is amusing in some situations, but when you’re talking about major international relations it’s not so amusing. He’s totally unelected, he’s not supposed to be running American foreign policy. Everything he’s doing is so over the top.

Narrator: In June, Hearst decided to set sail as a war correspondent. He assembled a traveling party that included several private chefs, cases of champagne, and the Willson sisters, and they all arrived right before the American invasion.

Hearst cabled Phoebe, “At front and absolutely safe so don’t worry. … There is no opportunity for us to get hurt even if we wanted to.”

Hearst did come under fire, and one of his reporters was badly wounded.

“I’m sorry you’re hurt,” Hearst told the poor man, “but wasn’t it a splendid fight?”

Patrolling the island on his yacht, Hearst answered to no one but himself. He boarded an abandoned enemy vessel, and collected little souvenirs. On the fourth of July, Hearst picked up starving Spanish sailors, and declared them his prisoners of war.

The publisher had done much more than report the news. He’d made the news.

In the end, Hearst was on the island for a month. The fighting he’d come to cover was over. The conflict -- in which 2,000 Americans had died -- heralded the rise of the United States as an imperial power.

For Hearst, the war had every making of a major victory.

Earlier that winter, on February 17th, Hearst had printed the first ever million-copy run in American history. It was a prize Pulitzer had long dreamed of, but never achieved.

For the first time in over a decade, a paper other than the World stood atop the New York City market.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: Hearst returns home. He thinks, “Well, I've won the New York penny newspaper war against Joe Pulitzer, what's next? Where can I advance my empire?” For Hearst, when one dragon is slayed, you move on to the next one. You don’t rest on your laurels. That was not his style.

Fallout

Erik Loomis, Historian: In the 1890s, newspapers were sold by young children who were at the bottom of society. There was no social safety net in America. And so you have these young children who either are orphans or their parents are working sixteen hours a day or have disappeared or have lost control of them.

Greg Young, Writer: Sometimes they were homeless. A lot of them were children as young as five or six years old who would stand on a street corner all day, morning till night, hawking these newspapers.

Andie Tucher, Historian: The newsies were out there in all weathers. They often were living extremely precarious lives and they were absolutely critical for the distribution of newspapers at this point.

Narrator: As Hearst’s influence grew, he relied more and more on the newsboys. They were the engine that fueled the Journal’s expansion, and most New Yorkers simply couldn’t get a paper without them.

Erik Loomis, Historian: These newsies, they would have to buy the newspapers. Now, if they sold all the papers, they made some money. But if they didn’t, they took a loss. In 1898, Hearst and Pulitzer, because they are funding these big news expenditures in Cuba, they raised the price of the papers from 50 cents per hundred to 60 cents. And at first, so many newspapers were flying out of their hands because people were so invested in this war that it was okay. But then 1899 comes, the war ends. People stop buying papers at the same level. And the kids are stuck.

Greg Young, Writer: After the Spanish-American War, most of the papers in town priced their papers lower again to their newsies. But The World and The Journal kept their whole sale price at that higher rate. So of course, this enraged all these children who needed to get by, who needed to make ends meet.

Narrator: On July 19th, more than five thousand newsboys went out on strike. The presses were still churning off the morning editions, but now the papers could find no buyers. Armed with clubs and rotten fruit, they marched to Hearst’s headquarters on Newspaper Row, and refused to pick up a single edition.

Kid Blink, one of the strike’s leaders, demanded justice: “Ain’t that ten cents worth as much to us as it is to Hearst and Pulitzer who are millionaires? … If they can’t spare it, how can we?”

Greg Young, Writer: A lot of people took the side of the newsies. The labor unions of the city, of course their parents, but of course, the rival competing newspapers of the World and Journal.

Narrator: The Sun and the Herald were more than happy to make a run for Hearst and Pulitzer’s working class readers, and proudly advertised the newsboys’ cause in their own editions.

Meanwhile, the young newsies had formed their own union.

Erik Loomis, Historian: The labor leaders from around this city come and they support them so politicians come out and support them, and all of a sudden, Hearst is sort of like what’s going on here? He’s fine with these worker movements so long as they don’t challenge him. And once they do, he’ll turn very quickly.

Narrator: Both Hearst and Pulitzer tried to hire scabs, looking to the city’s population of homeless and destitute adults. But the newsies beat the publishers even to the flophouses, and turned opinion in their favor.

“Every one of us has decided to stick by the newsboys,” one man said, “we won’t sell no papers.” Daily circulation plummeted. The World was cut by more than two thirds. And it was just as bleak over at the Journal.

In the end, the publishing giants were forced to compromise. They agreed to buy back any papers that the newsies couldn’t sell. But they still kept prices high, and they broke up the union.

Chenjerai Kumanyika, Media Scholar: Hearst standing up for common people is a strategy of business for him. Even when he’s championing populist politics, he’s kind of like, ‘I support that to the extent that it supports me.’ So, you know, that’s what I think we actually have to look at, right? It’s like that’s the more complicated story.

Erik Loomis, Historian: One of the richest men in the world literally cannot stand the poorest people in the country, people he directly relies on to sell his newspapers, from getting even a dime more if it negatively impacts him.

Narrator: As the strike came to a close, so too did the newspaper war between William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer. The World would remain in print, but would never again recapture its old spirit, and its publisher slowly withdrew from public life.

Andie Tucher, Historian: Pulitzer was embarrassed by the lengths he had gone to in order to compete with Hearst. We believe that that was one of the reasons that he gave his money to found the Columbia Journalism School, in remorse for the excesses that he countenanced.

Narrator: Under the golden dome of The World, Pulitzer’s senior editors called a massive meeting.

“There is and has been for years … a fierce competition,” they acknowledged. “The great mistakes which have been made have been caused by an excess of zeal.”

“The World,” they concluded, “feels that it is time for the staff to learn definitely and finally that it must be a normal newspaper.”

For Pulitzer, there came a reckoning. But if Hearst had any regrets about the part he’d played, he didn’t let on. He was already focused on his next move, eager to test his powers of persuasion in yet another rough and tumble arena.

A Stolen Election

Narrator: On October, 13, 1905, Hearst found himself lost in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, with a gaggle of political advisors and journalists. It was an inauspicious start to that year’s mayoral election -- and this time, the candidate was none other than Hearst himself.

David Nasaw, Author: This man is incredibly restless, he's incredibly ambitious and you put the two of them together, he can’t sit still for long. Having conquered New York as a journalist and as a newspaperman, he wants to do something else.

Erik Loomis, Historian: Hearst understands very early on that his newspapers can do a whole lot more than what newspapers had been doing over the last 100 years to promote a whole different way of thinking about the world and one that promotes Hearst himself as one potentially the person who can have the solution to these problems that are facing America.

Robert Chiles, Historian: On the one hand, he's already been in politics for a long time as a publisher and as a particularly partisan publisher at that, he has a clear set of beliefs that he has articulated. He has an agenda that is clearly resonating with a large segment of society. And he has something else which is a clear lust for power.

Narrator: His career in politics began with a run for Congress in 1902. His working-class readers seemed to have forgiven him for his role in the newsie strike, and elected him by a landslide. No sooner was Hearst the representative for the Eleventh District of New York than he was running again -- this time for the democratic nomination for president.

He campaigned energetically across the country, chartering a special train, and using the Hearst papers to boost his chances everywhere he went.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: Hearst as a political candidate realized that if you want to pick up votes, delegates, influence in the midwest, you have to have a Chicago newspaper.

Narrator: He bought two: the Chicago American in 1900 and then the Chicago Examiner two years later -- but even his expanding stable couldn’t secure the nomination.

Now, he’d split with the democratic party and was running for mayor on his own third-party ticket, at the head of the Municipal Ownership League.

To make himself presentable to voters, Hearst had had to remake himself. He retired his [loud] plaid suits, and now routinely sported a sedate new uniform -- a black hat and a long black coat -- that made him look more like an undertaker than the bad boy of U.S. journalism.

Everywhere the candidate went, Millicent was by his side -- but the young woman was no mere show girl -- that was Mrs. Hearst.

They’d been married at Grace Church, back in the spring of 1903.

Phoebe had not attended.

Victoria Kastner, Writer: Phoebe didn’t meet her daughter-in-law until long after the wedding. She was not too keen on having -- after all of this effort, trying to separate her son from various actresses and opera singers -- here he’s gone and married a stage actress.

Narrator: Phoebe did send an emerald brooch to her son’s bride, but all the while kept close tabs on how the match was received by polite society. “Quite a number of people like her,” Phoebe reluctantly admitted, and there certainly was no denying that her son seemed especially pleased with himself.

David Nasaw, Author: Everybody thinks that Hearst marries Millicent Willson because he needs to be more respectable and it’s true. He decides that Millicent can be perfectly respectable looking and any wife is better than no wife.

Narrator: Ring on his finger and somber wardrobe notwithstanding, Hearst the candidate in fact remained the same man as ever.

Instead of moving his new wife into a townhouse on Fifth Avenue, he chose a brand new apartment building called the Clarendon, on the Upper West Side -- a location that just two decades earlier had been grazing land for the city’s livestock, and remained about as far as could be from the usual haunts of the old New York elite.

But the Hearsts were no less comfortable here, and now occupied the penthouse, a 7,000-square foot affair, over three floors, with sweeping views of the Hudson River and the entire city. From this high perch, Hearst launched his run for mayor.

His campaign took up the same causes that had made the Journal the leading paper in the city.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: He was arguing for income taxes on the rich, an 8-hour working day, the destruction of trusts. All of these positions were fairly radical at the time.

David Nasaw, Author: He was a good progressive. He wanted the city to own the streetcars, to own the gasworks, to own the sewers, to own the waterworks, so that there would be less corruption, less graft. That, of course, would take all the money away from Tammany Hall.

Narrator: Tammany was the most notorious democratic political organization in New York. Known simply as ‘the machine,’ for decades it controlled the city’s politics through a powerful mix of corruption, intimidation, and outright violence. They ran everything -- businesses both legal and illegal: construction, sanitation, firefighting -- and, of course, state and local elections. The machine relied on thugs, like the members of the notorious Eastman Gang, to keep people in line. As a party boss once said, “the way to have power is to take it.”

Robert Chiles, Historian: The key to the machine’s success, the key to their domination of the city for many decades, was the desperation of the immigrants and working class voters. Tammany Hall has young men who are aspiring to move up in New York City life and they know the problems of everyone in their building, everyone on their block, and they report back to the ward boss, they say, ‘this family can’t make ends meet because the dad got injured on the job.’ Well, Tammany shows up, and they give them a turkey. The widow upstairs, they make sure they have a bucket of coal, she’s not going to go cold this winter. And all they ask in return is your vote. And so they don’t want reform. They’re not interested in addressing the actual conditions that are responsible for all that suffering. What this leaves is an opening for more radical critiques of the status quo -- that means an opening for Hearst.

Narrator: On the campaign trail, Hearst’s PR machine worked tirelessly to show that their candidate was in nobody’s pocket, and wasn’t afraid of anybody.

As election day neared, even rival papers could not ignore the enthusiasm that Hearst was finding among the people. “William Randolph Hearst drove through the Lower East Side last night in a procession of triumph,” The World reported, “the like of which has not been seen in New York in many years.”

After hosting one more elaborate rally at Madison Square Garden, all Hearst could do now was wait. As he cast his vote on East 29th Street, there were rumors of violence in locations across the city, but he remained undaunted, predicting a landslide. “I am confident,” he said in a statement that verged on a victory speech, “[And] I shall always feel deeply grateful for the great kindness that has been shown me by my fellow citizens in this campaign.”

David Nasaw, Author: How could he lose? Because Tammany knows they're in trouble and from the very beginning they send their tough guys into the voting precincts where Hearst is gonna win. It is an outrage of gargantuan proportions.

Narrator: Just as they’d done so many times before, Tammany resorted to every underhanded trick in their extensive repertoire.

They had attacked Hearst’s polls watchers. One man had a finger chewed off, and his face slashed. Tammany then flooded the race with fraudulent votes, tipping the election in favor of their own candidate, George McClellan Jr., who would go on to serve for another four terms.

“We have won the election,” a furious Hearst told the Times. “Illegal voting and dishonest count have not been able to overcome a great popular majority.” He demanded an investigation.

But it would be to no avail. There would be no recount. As Tammany celebrated its latest victory, ballot boxes filled with the votes that would have put Hearst in the mayor’s office, drifted slowly down the East River, and on out of sight.

What Goes Around Comes Around

David Nasaw, Author: Hearst never expects to lose anything. And when he does lose, he’s shattered, but not for long. … because his confidence in himself is such--and his confidence that he knows America and he knows the voters. He knows the newspaper readers is such that he bounces back. And eventually, he will vanquish his enemies, he will defeat his opponents and the people of America will understand that this is the man they need because he’s for them.

Narrator: By the spring of 1906, Hearst was hailed as the foremost figure in American journalism.

The fact that he should have been sitting in the mayor’s office in no way blunted his political ambition. He confided to his editor and friend Arthur Brisbane that the loss was a “tragedy for the people,” but added, “Our next effort will be the most important thus far.”

“We will,” he informed Brisbane, “run for Governor as planned.”

Gary Kamiya, Writer: Whatever it was that pushed him on was incredibly deep. The fact that he was so irrepressible, there's something you have to at least like, you know, respect about the guy’s sheer strength.

Greg Young, Writer: He has this kind of Teflon ambition He thinks that he can do no wrong and at one point is just going to click. And one point he's going to be able to get the power that he needs, the power that he wants.

Narrator: Now, however, his critics and political enemies had found a new strategy, taking a page right out of Hearst’s own playbook. No sooner had he begun his gubernatorial campaign, than they launched a series of vitriolic attacks against him. And one story in particular seemed to follow the candidate everywhere he went.

In 1900, Hearst had printed his usual brand of attacks against then President William McKinley.

Andie Tucher, Historian: He had published a doggerel verse, a really stupid poem, that seemed to suggest that McKinley -- who his opponents used to say had the backbone of an éclair -- that the world would be better off if he were assassinated.

Narrator: Then, in 1901, he’d run an editorial arguing that, “If bad institutions and bad men can be got rid of only by killing, then killing must be done.”

That had been the year of the World’s Fair, in Buffalo, New York. On September 6th, McKinley himself had visited. While the President stood greeting members of the public, a young man approached. He shot the president twice, at point blank range. When McKinley died from his wounds, Hearst’s many rivals were more than happy to blame the publisher, even though the assassin, Leon Czolgosz, was an anarchist from Michigan who’d never seen a Hearst paper.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: Hearst certainly was merciless in his attacks on McKinley and used all the tricks in his trade but that was standard journalistic warfare, they wasn’t anything that any objective person could look at and say, ‘Oh, William Randolph Hearst is responsible for the assassination of William McKinley.’

Narrator: Now, in October 1906 -- when Hearst pulled ahead of Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes and took one step closer to the Governor’s Mansion in Albany -- even the White House got involved. President Theodore Roosevelt denounced Hearst as “the most potent single influence for evil that we have in our life” and had his secretary of state, among others, play up the assassination for all it was worth. The story was spread so widely that Hearst’s working-class supporters could no longer ignore it.

It was practically impossible, one of Hearst’s collaborators would later remember, to “describe the hate [in] those days.”

Robert Chiles, Historian: When you're engaging in the sort of yellow journalism, the sort of scandal mongering, the sort of lies, the sort of demagoguery that Hearst is engaging in and willing to use, You’re going to have to expect that what goes around comes around. Hearst had crossed swords with a lot of incredibly powerful people and powerful interests.

Jeet Heer, Writer: That really made him the enemy of the economic elite and respectable society and old money which saw him as--I don't think it's too far to say, they saw him as the Antichrist. They saw him as a figure that would destroy American society. You know, like a socialist.

Gary Kamiya, Writer: One of the reasons that he was so bitterly assailed was that he expressed his positions in such hyperbolic and, you know. villain against good guys ways that it upped the emotional ante of the argument.

Narrator: In the end, Hearst lost the race for governor, then, three years later, he lost another run for mayor. In total he had launched six major campaigns, but would never again hold elected office.

Robert Chiles, Historian: The fact that Hearst keeps running for public office despite so many failures, you could attribute to a genuine belief that he is this great champion of all of these important causes for the kind of people that are buying his newspapers and for whom he purports to care deeply, or you could attribute it to profound egomania. In Hearst's case I think it's a little bit of both.

David Nasaw, Author: He never doubted himself, there was no gray in his universe, everything was black or white, everything was right or wrong, and he was always right and his opponents were always wrong. And because he was only right, he couldn't give in to them. He couldn't stop pushing.

Narrator: Hearst now had a paper on each coast, two in the heartland, and he kept tabs on everything that appeared in all of them. He worked harder than ever, traveled more and more, slept less and less. He’d once run himself so ragged that he’d been forced to retire to a sanatorium in Michigan.

“The work and worry about the papers and campaign and everything broke Will down,” Millicent wrote to Phoebe. “The papers get in every morning, and there is always something the matter with them. I think we shall have to go someplace where there are no papers.” But Hearst would never agree to that, and he soon returned to New York.

Victoria Kastner, Writer: As WR got older I think Phoebe worried about whether or not he was taking sufficient care of himself, because he pushed himself extremely hard. And she, I think, and Millie began to align by worrying that WR was taking on too much.

Narrator: For all his drive and assurance, the one thing Hearst didn’t seem to know was when to stop. He soon jumped at the opportunity to test the speed of a newfangled biplane, keen to try for himself the brand new field of aviation. He was determined to turn even this to his advantage, publishing the news in all his papers.

By 1909 he’d started to accumulate media properties on a whole new scale. He bought four new papers. Soon, the people of Los Angeles, Atlanta, Boston, and Washington, D.C., could all turn to his front page to get his take on what mattered most.

Hearst then moved into magazines, founded Motor, purchased Cosmopolitan, and would soon add Good Housekeeping, Town and Country, and Harper’s Bazaar to expand his reach further still.

If he was never going to rule from Washington, he resolved to forge another path -- and create something, perhaps, that might become more powerful than presidents.

After hearing of her son’s plans, an old family friend at once wrote to Phoebe: “He [means],” he told her, “to control the press … It is madness.”

At 46, Hearst had vision and daring enough to dream up an entirely new kind of media power -- but, as ever, he owed it all to his mother.

Unleashed

Narrator: On October 29th, 1911, American journalism lost one of its most successful sons. The next day, a signed editorial appeared in all the Hearst newspapers.