Narrator: For many of the women the sight was overwhelming: U.S. cavalry appearing over the horizon, closing in on their encampment near Wounded Knee. Some of them began to cry; the men tried to comfort them. The soldiers marched steadily forward.

The high wailing of the women blended with the tinkling bells of a merry-go-round, with the sounds of the cars that were still arriving, and of the spectators who had come in from all over Nebraska and South Dakota. At the center of it all was one of the most famous people in the world: William Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill.

The sixty-seven-year-old Cody was directing his first movie — a reenactment of the Wounded Knee massacre — and doing what he had always done: blurring the line between truth and entertainment, history and myth.

Buffalo Bill Cody had lived both sides of that line. He had grown up in the real West, knew the sorrow and cruelty and courage that had created it. But he understood that the West was something more, even for those who would never see it…and that he could be the hero in the story they wanted to live.

Paul Fees, Historian: That myth of the West, all of those things that we tend to think of as the Western adventure, somehow it was all wrapped up in the person of Buffalo Bill.

Louis Warren, Biographer: He connects us to a story that is at the heart of the American experience. And he made the American West into the American story.

Narrator: In 1866 the twenty-year old William Cody was adrift in the wake of the Civil War. His boyhood home was gone, most of his family dead. He left behind the remains of his past and joined the flood of young men heading West. “I sighed for the freedom of the plains,” he later recalled; “I started out alone for Saline, Kansas, which was then the end of the track.”

Paul Fees, Historian: Kansas must have been an enormously exciting place. Lots of soldiers suddenly out on their own, the railroads building, the army moving out on the plains to resume their war on the Plains Indians, yeah, a very interesting place for people on the make. And Cody certainly was on the make.

Narrator: He was at home with the tracklayers, bullwhackers, speculators, and cowboys who congregated in the towns that were springing up as the rails pushed West. Life was exciting and sometimes dangerous but after all, he’d spent much of the Civil War riding with Union irregulars — rough customers…he could handle himself.

Charles Scoggin, Writer: He was well over six feet tall. Very attractive. And this is a time when the average height was like, you know, five and a half feet. So he really he stood out in a crowd.

Narrator: He had the brash confidence that sometimes comes of hardship and loss. He could drink with the best of them, and often did. But Cody was a bit of a loner; he kept his many companions at arm’s length. In fact, it might have come as a surprise to his drinking buddies that Bill Cody had left a wife behind.

He’d met Louisa Frederici in St. Louis at the end of the war. They weren’t a perfect match.

Charles Scoggin, Writer: You’ve got Cody who’s a kid that’s grown up in eastern Kansas, has been out West and lived a pretty rugged life. And she grows up in the French quarter of St. Louis. Goes to Catholic convent school.

Paul Fees, Historian: Golly, she’s, in her pictures she’s, she’s almost sultry looking. And she must have seemed terribly exotic to him. And his was a life then of trying to make a home for her. But he wasn’t good at that part.

Narrator: Louisa had warned Cody that she didn’t want any roving plainsman for a husband. But he just couldn’t settle down: it was only six months after their wedding that he’d headed off to west Kansas, leaving her at his sister’s home, alone and pregnant. But he didn’t forget about her. He sent home whatever money he could, and lived a hard life to do so.

Cody finally got a bit of a break in the spring of 1868 when U.S. Army officers at Fort Hays hired him to help track down some deserters. For Cody the best part of the job was the company he got to keep: the deputy marshal from nearby Junction City.

James Butler Hickok was already well known as Wild Bill.

Louis Warren, Biographer: Wild Bill is a scout for the army. He occasionally acts as US detective, which means he’s in charge of tracking down deserters. And then in 1867 Wild Bill Hickok became the subject of a magazine article in Harpers New Monthly Magazine.

Paul Fees, Historian: It made Hickok into what, for Easterners, seemed the very embodiment of kind of a flamboyant Western, dangerous hero or anti-hero even. So Hickok became famous largely through his own flamboyance but also through publicity.

Narrator: Hickok made a habit of waiting on railway platforms for Eastern tourists. He knew what they wanted to see and he dressed the part, wearing clothes that would have suited Daniel Boone’s Kentucky better than post-Civil War Kansas.

Louis Warren, Biographer: Cody looks at Wild Bill and sees Hickok running what is kind of a one-man show and the show is the life of Wild Bill Hickok. And he starts to think maybe I could do that.

Cody begins to wear his hair long. He begins to put on buckskin. He begins to tell some of the same stories that Hickok has told only he features himself at the center of those stories instead of Hickok.

Narrator: Easterners pictured frontier life as a heroic struggle to bring civilization to the West and subdue Indian savagery. In fact, a demoralized army was stuck in an ugly war, fighting an elusive enemy in unfamiliar terrain. Scouts were crucial, and Cody was good. As the war with the Plains Indians heated up in the late 1860s, Cody would fight in more battles than most full-time soldiers.

He liked scouting: it was adventuresome and it paid well. What’s more, it was stable enough that Louisa brought their daughter and rejoined him at Fort McPherson. The next year the couple had a second child, a boy they named after the famous scout, Kit Carson.

But Cody always had his eye on the horizon, looking for the next chance. In the summer of 1869 that chance turned up in the person of a New York writer who went by the name of Ned Buntline. Buntline had plenty of reasons for using an alias: on more than one occasion he’d neglected to get rid of one wife before marrying another, and despite this surplus of wives had found the energy to kill a man in duel over a yet another woman. But he was also one of the most successful writers of the day.

Charles Scoggin, Writer: Buntline is looking for somebody to write a book about. And it was going to be Wild Bill Hickok by most accounts. Hickok either wasn’t available or refused to talk to him or what have you. And he decides to write a book about Cody which is called “Buffalo Bill: King of the Bordermen.” The book finally gets serialized in one of the New York publications. And at that point Cody suddenly becomes a real celebrity.

Narrator: Buffalo Bill joined a growing band of frontier heroes, idols of a public fascinated by the West. For most Americans that West existed only in dime novels and story papers. But the wealthy and well-connected could live out their Western fantasies. Soon, eastern sports were saddling up to hunt buffalo, led by famous scouts like Buffalo Bill.

Louis Warren, Biographer: But very few of these men knew how hard this actually was. The most common mishap was for a hunter to shoot his own horse through the head. One guide said the safest place to be with a party of dudes is nearest the buffalo. And Cody was hunting with these men and they adored him. Because not only did he look the part of a Western hero, but he cultivated his skills as a horseback hunter in ways that few other people had. One of his biggest critics actually said I saw him shoot sixteen buffalo from the back of a horse that was frightened of buffalo using sixteen shots. It was the most spectacular exhibition of buffalo hunting he’d ever seen. That’s what these dudes are paying for in part is to be in the company of somebody who’s like that.

Narrator: Cody was brushing elbows with men from the most rarefied circles of society. Their adulation was new to him; he was becoming aware of his own charisma, and of how far that might take him.

Just three years after Louisa had moved to Fort McPherson, Cody left the family behind again: he took Ned Buntline up on an offer to come to Chicago. Instead of telling his stories to well-heeled tourists, Buffalo Bill would bring the West to audiences who could only dream of the frontier.

Paul Fees, Historian: Cody agreed to appear in a play that Buntline supposedly had written for him. Now, Buffalo Bill himself was probably inclined to do this. But he had a pal, Texas Jack Omohundro, who was almost clamoring to become part of this.

Bobby Bridger, Writer: When they got to Chicago they found that Buntline hadn’t written the play yet. When the word got out that the play had not been written the, the man who owned the theater backed out of the production. And so Buntline had to borrow the money from Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill to rent the theater. And I think that says a lot about Ned Buntline.

Louis Warren, Biographer: Buntline says don’t worry about it, don’t worry about it. Takes him to a hotel. Gets him into a hotel room and says he’ll be back in a little bit with the play. And four hours later he leapt up from his desk allegedly and shouted “Hurrah, hurrah for Scouts of the Plains. That’s the title of the play. It’s finished!”

Bobby Bridger, Writer: These two men that Buntline brought to the theater were totally inexperienced. They had a terrible time remembering their lines. And when they got out on stage they just were absolutely stone cold petrified. Buntline started coaching them on stage and trying to throw lines to them that they froze and wouldn’t respond to. So finally in desperation he asked Cody what have you been doing? And Cody saw a friend of his out in the audience and said I’ve been on a hunt with Mulligan up there.

Louis Warren, Biographer: And then he proceeds to tell stories about the hunt, and the crowd just loved it. They just roared. And in fact, Cody would recount that he did not utter one word of his lines that whole night. That he just made up stories.

Bobby Bridger, Writer: At that moment Buffalo Bill realized that people would come to see the star more than they would the show. And from that point forward he was the star.

Narrator: “Such incongruous drama, execrable acting, intolerable stanch, blood and thunder,” one critic wrote, “is not likely to be vouchsafed to a city a second time, even Chicago.” Incongruous, execrable and intolerable it might have been, but the company played to packed houses for the rest of the season.

Louis Warren, Biographer: But there are plenty of signs along the way that this was a partnership that wouldn’t work out for Cody. Buntline had a long history as not only a novelist and playwright but as a rabble rouser. He was a founding member of the Know Nothing Party, which was really a party of Nativists, that is they’re strongly anti-immigrant.

Narrator: Back in the 1850s Buntline had been arrested for inciting anti-German violence in St. Louis. He’d skipped bail and left town, but he hadn’t been forgotten. When Scouts of the Plains traveled to St. Louis, all three men were arrested. Cody and Omohundro were quickly released, and Buntline managed to skip bail yet again.

Louis Warren, Biographer: It was becoming apparent to Cody that Buntline had a lot of baggage and that maybe Buntline’s plans for the Buffalo Bill character or figure weren’t in Cody’s plans. Buntline appears to have hoped that Cody would become a kind of anti-immigrant figure, a kind of, of Nativist hero. And Cody, for reasons of his own, didn’t want to go there.

Narrator: Cody had grown up in Kansas before the Civil War, when it was the most dangerous place in America. Pro-slavery neighbors and militias had terrorized the family. When Cody’s father spoke out against slavery at a town meeting, he was stabbed by a neighbor as the eight-year old boy looked on Cody would become the family’s main breadwinner three years later, when his father finally died of his wounds. One loss followed another: a brother, his father, his mother, a sister, a second brother.

The specter of death followed him always. In the spring of 1876 it suddenly caught up with him. He was on the road with his theater combination when he received an urgent telegram from Louisa. Their son Kit had contracted scarlet fever. Cody rushed home, but the boy died in his arms a few hours later. “Louisa is worn out and sick,” he wrote to his sister. “We all clung to him and prayed God not to take from us our little boy. But there was no hope from the start.”

Paul Fees, Historian: His grief was intense. It was real. But at the same time he wasn’t able to help his wife through that, that terrible grief. And, and instead he did what he did so often in their marriage, he fled.

Louis Warren, Biographer: Cody veers away from the darkness almost always. He doesn’t like to focus on sad stories. He doesn’t like to talk about pain. He likes to focus on triumph and victory. And this would serve him very, very well in show business. In his personal life it probably served him less well.

Paul Fees, Historian: Cody got a summons that must have seemed providential to come West and rejoin General Carr in the 5th Cavalry. So he went.

Louis Warren, Biographer: Cody’s company’s with the 5th Cavalry and they get word that Custer and most of his command have died on the banks of the Little Big Horn River. And they’re shocked.

Narrator: By 1876 Americans had been assured that the Indian Wars were all but over. Out of the blue, a host of warriors had annihilated an army detachment led by one of its most famous generals. All eyes were on the West, where Cody and the Fifth Cavalry were searching for hundreds of Cheyenne. The high command was panicked, the public wanted revenge. Cody saw his chance to write Buffalo Bill into Custer’s high drama.

Louis Warren, Biographer: Cody hits on this idea that he can live his life, live this story, for the entertainment of his audience.

Charles Scoggin, Writer: What’s really bizarre about this whole thing. It really is bizarre. Cody gets dressed up literally in his stage costume. Black pants with piping down the front, silver buttons down the side, a red silk shirt, and his big hat. And he’s going to go out and kill an Indian.

Narrator: The climactic battle never happened. The only action that the Fifth Cavalry saw was a skirmish with a half dozen luckless Cheyenne, in which Cody shot and killed a warrior named Yellow Hair. He had killed other Indians before, but now, for the first and only time in his life, he walked over to the body, crouched down, and cut off its scalp.

The incident barely rated a mention in the Army report, but within a few months Cody was reenacting it for audiences from New York to St. Louis in a play called “The Red Right Hand, or Buffalo Bill’s First Scalp for Custer.” He sported the same velvet costume he had worn that day, used the same knife, and hoisted the real scalp at the climax of the performance. He had crossed a threshold. William Cody had become Buffalo Bill.

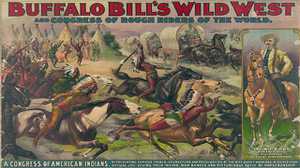

By 1883 Cody had become a star of frontier melodramas: lowbrow spectacles featuring the rescue of a white woman from the clutches of Indians, Confederate sympathizers, Mormons, or the like. He was a hero to the workingmen who crowded the theaters, but he wanted a bigger, more respectable audience. He teamed up with a sharpshooter named Doc Carver to put on a new kind of show. “Our entertainment don’t want to smack of a circus,” he wrote Carver, “must be on a high toned basis.” They called it “Buffalo Bill and Doc Carver’s Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition.” Everybody else just called it “The Wild West.”

Charles Scoggin, Writer: They got some wild steers that they can ride. They got bucking horses. They’ve got buffalo. And the other thing they got a lot of is evidently alcohol. And there are legendary stories; supposedly they had a car full of alcohol. Whatever it was, both Carver and Cody would really go on some pretty, pretty good drunks. I think Cody definitely had a problem with binge drinking, there’s no question about it. So they travel around the country with this show sometimes not making the performances because they’re you know dead drunk literally. Carver’s got a terrible temper. I mean at one point he’s the trick shot in the show and he puts on a lousy performance and he’s so frustrated that he breaks his rifle over the head of his horse and beats up his assistant who’s throwing the ball in the air. I mean it’s that sort of thing.

Narrator: The Wild West staggered through to the end of the season, and then Cody went off to meet Nate Salsbury, a successful, experienced, and sober, manager.

Louis Warren, Biographer: Cody had had enough. He said, you come on board, and help me out with this or I’m going to quit. I wouldn’t go through another summer like this for a hundred thousand dollars.

Narrator: Over the next three years Cody and Salsbury overhauled the Wild West, adding acts and giving it a story line. Every year the crowds grew bigger, every year the two owners reinvested their profits — in 1885 alone they cleared over $100,000. When he was a young man, Cody had sighed for the freedom of the plains. Now he realized that millions of people shared his longing.

Patricia Nelson Limerick, Historian: As the majority of Americans are moving into cities, working in offices, working in factories, they’re yearning, their imaginations are pent up and are wanting some place to run free. Setting our minds West, that turns out to be the, the thing to do. It’s just it’s a wonderful thing to think that there’s a different way of living and I can at least spend my leisure time imagining that.

Narrator: In 1886, the Wild West played to over a million people in New York. Mark Twain and P.T. Barnum both showed up and gave Cody the same advice. As Barnum put it, if they “take this show to Europe they will astonish the Old World.”

Narrator: The following spring Cody, Salsbury, and the Wild West left New York harbor for England. The Wild West had become one of the most elaborate shows on earth. In a stadium near London, workers used seventeen thousand carloads of rock and earth to build the mountains in a sweeping Western landscape. Two hundred cast members: cowboys, Native Americans, vaqueros, stars like Annie Oakley and Buffalo Bill himself, along with hundreds of horses, buffalo, mules, elk, steers, donkeys, and deer all moved into an encampment on the grounds.

Charles Scoggin, Writer: Essentially, everybody had a backstage pass. You could wander around and see the performers and such, see what’s going on. One of the things that might be most impressive as you first walk in is what it must have smelled like. And of course the noise. In the background the Cowboy Band is playing and you’re getting ready to see this show.

Juti Winchester, Historian: You had people to sell tickets. There were people to count the tickets. People to count the money and there was plenty of that.

Louis Warren, Biographer: There were butchers who traveled with the show. There were bakers. There were pastry chefs. There was a whole kitchen full of, of cooks. There are blacksmiths, there are wheelwrights.

L. G. Moses, Historian: Spectators were invited to go into the Indian villages to see how the people themselves lived and also to see how they shared that life with other members of the show.

Paul Fees, Historian: The Wild West was an experience for people, not just a show. When the show began, it began with a bang.

Juti Winchester, Historian: And then this man comes out and your dad is giving you the elbow and saying, look at that man. Remember you’ve seen Buffalo Bill Cody.

Paul Fees, Historian: Annie Oakley was a natural shooter. She never seemed to aim. She simply pointed toward the target and blew it away.

Juti Winchester, Historian: Well she could take a mirror and shoot an apple off the head of her faithful dog. She could split a playing card. If you held a playing card she could split it.

Cody took a lot of responsibility about making sure that everything ran according to plan and that people were at their best when they performed. There are photographs of him peeking through a hole in the tent watching the show and making sure that everybody was cued correctly.

L. G. Moses, Historian: There would be Indians leaving their horses and sneaking up upon the settlers. Coming to the rescue was Buffalo Bill and the cowboys and the Indians would race off. And Cody and his cowboys would have made the frontier once again safe for settlers.

Charles Scoggin, Writer: Cody had the reenactment of the Battle of Little Big Horn. They reenact the whole thing. Custer and his command are all dead. But Cody rides into the scene and it’s flashed on the, the curtain of the stage, “Too Late.” As if Cody could have saved Custer.

Paul Fees, Historian: So it would have been just an assault on the senses to the time two and a half hours after the show began that people began to go home.

Narrator: Buffalo Bill was a sensation. One distinguished fan wrote in her diary with the excitement of a schoolgirl: “An attack on a coach and on a ranch, with an immense deal of firing, was most exciting, so was the buffalo hunt and the bucking ponies that were impossible to sit.” Queen Victoria’s enthusiasm was contagious: on the eve of the great ceremony marking her Golden Jubilee, the royalty of thirteen countries followed her example and went to see Buffalo Bill.

Four years after treating audiences to the spectacle of Doc Carver coming unhinged, Cody was charming his way through the salons of London, and needed a secretary to manage his social engagements.

Juti Winchester, Historian: He had a natural charisma, you know. When, when they describe him he stands straight as an arrow. He has a mild voice, a soft eye — nature’s nobleman as they liked to say. So he could be an asset to your party to have this colorful man you know rubbing elbows with your guests.

Narrator: His personal life was another matter: Louisa stayed in Nebraska, and the two rarely communicated. It was easy to ignore distant problems with the world at his feet.

He would spend most of the next five years in Europe. Three full trains carried the show to Paris, Rome, Barcelona, and Berlin. Buffalo Bill had become America’s first cultural export.

Patricia Nelson Limerick, Historian: Europeans do not know what to make of the United States. It’s a problem. It has the poor taste to revolt and become an independent nation and then become quite a swaggering, confident nation. To have to have something that causes Europeans to say wow we love that. That’s in some ways the end of the American Revolution.

Narrator: Cody wrote home to friends trying to explain what had happened in Europe: “There was never anything like it ever known, and never will be again.” He was right about one thing: there had never been anything like Buffalo Bill.

Charles Scoggin, Writer: He invented the genre of celebrity. One reason he was able to do it, is there was now an infrastructure that you could have international celebrities.

Narrator: The telegraph, the railroad, cheap printing, and a public hungry for entertainment: Cody and his managers put the pieces together. They were discovering that you could be famous for being famous.

Paul Fees, Historian: Buffalo Bill had a brilliant publicist, Arizona John Burke, who managed to get Cody into print probably more than any other man of his time. And eventually Cody’s face, his image, became so well known that a poster just bearing his image on a buffalo, of course, could be labeled “I Am Coming,” with no mention of Buffalo Bill or Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

Narrator: Buffalo Bill would never have been famous, would never have had a story to tell, without Native Americans. He had built the Wild West around the Sioux he had been fighting only a few years before. In 1885, only nine years after Custer’s Last Stand, he convinced the most famous Native American of all, Sitting Bull, to join the Wild West.

Juti Winchester, Historian: Well, Sitting Bull was kind of the focus figure for the public’s horror and anger over Little Bighorn. And here it is not very many years after all of this. I think the public had this combination of fascination and horror; they’re going to go and look at the man who wreaked such havoc on American dreams; almost like this morbid fascination they had.

Narrator: It was a publicist’s dream: Foes in ’76, Friends in ’85. Sitting Bull did get on famously with Cody but he lasted only one season: he hated the noise and the squalor of the Eastern cities. “The white man knows how to make everything,” he told a reporter, “but he does not know how to distribute it.”

Sitting Bull had had enough, but hundreds of his fellow Sioux would follow him to the Wild West. Some were overwhelmed, but many more took to their new lives. When they got to Europe they were treated as minor celebrities, their every move reported in the papers. But for Native Americans back home on the Plains, it was another story. In December of 1890, four centuries of Indian wars finally ended in the massacre at Wounded Knee.

Guy Dull Knife, Grandson of George Dull Knife: My grandfather at the time was pretty young. They lived not too far from Wounded Knee. And I guess they could hear those guns going off over there. And my grandfather said they went over there after. And the bodies were still all laying out there when my grandfather went out there.

Narrator: George Dull Knife had been an infant at the time of the Little Bighorn. He had somehow survived the bullets, cold and hunger of the following years, as the United States relentlessly avenged Custer’s defeat. But the years after Wounded Knee were worse. On the reservations there was no hope, no way out.

Guy Dull Knife, Grandson of George Dull Knife: I guess there’s a rumor going around the reservation that you know there’s a show, and uh, a Wild West show… that was, you know they’re recruiting. His relatives you know they told him you know you better not go because you don’t know you don’t know what’s out there. But it was really hard times and you know people were starving and so, him and his friend, they went to Gordon to sign up. And they don’t know when they’re going to come back. And they don’t really know where they’re going either. The worst thing he said when they go overseas is that boat. Said we’re not, uh, we’re Plains Indians. We don’t know nothing about the ocean. So I can just imagine riding a boat for almost two weeks, you know. But Buffalo Bill I guess he makes his rounds, talks to people you know, and encourages them.

Narrator: The Wild West show was based on a familiar narrative: the triumph of white civilization over wilderness and savagery. The Show Indians attacked an emigrant train, a stagecoach, and a settler’s cabin, only to be foiled every time by Buffalo Bill. To Cody and his audiences, the superiority of white civilization was a given, and its victory inevitable.

But there was more to the show. Other scenes, and the encampment itself, offered white audiences a rare and sympathetic glimpse of Native American life. Cody no longer billed himself as “The Terror of the Red Men,” and he had stopped boasting about the first scalp for Custer. When he needed a break from the chaos and the crowds he slept in a teepee in the Indian village.

Guy Dull Knife, Grandson of George Dull Knife: My grandfather at the time he didn’t speak no English he kind of had a rough time. And Buffalo Bill noticed that. So he started teaching him. All the guys, whenever they get a chance you know he’ll sit down with them and teach them. So that’s how my grandfather learned how to read and write. In return they teach him how to speak Lakota, So over the years it got to the point where he understands Indian pretty good. He said they get to travel all over like you know they’re not doing nothing. Buffalo Bill takes them around. They even he even took them to see the Pope. That’s where my grandfather became a non-believer in Christianity.

L. G. Moses, Historian, Historian: In the opening of the Wild West Show Buffalo Bill came in followed by the Indians on horseback. And what film there is, is remarkable when you look at the faces of the Indians on horseback that they’re obviously having a good time and many of them are smiling and laughing; they’re just having a heck of a time. That is something that you cannot fake.

Guy Dull Knife, Grandson of George Dull Knife: All the Indians that like my grandfather they all liked him. Whenever they come back to Gordon from a show I guess they usually roll out a barrel of cognac or something they bring back from overseas. And they have a big party and then you know he goes his way. But this is, my grandpa said, looks like a lot of times he doesn’t want to you know. He likes what he does, you know. And likes his company, Indians and all these cowboys. I guess he really hates to leave them.

Louis Warren, Biographer: The pressures of the life that Cody was living were enormous.

Charles Scoggin, Writer: He’s feeling all this responsibility for people. He’s got all these ventures that he’s trying to make successful. He’s got all these people counting on him. And he becomes a pretty melancholy fellow. But he’s not William F. Cody. He’s Buffalo Bill. And he’s got to play that role twenty-four seven.

Louis Warren, Biographer: The image of Buffalo Bill as bon vivant was crucial to him and crucial to his success. But it was a very sort of public life which left him without much time for real friendships or for any kind of intimate relationships. In reality, he spent most of his nights in his railroad car alone.

Narrator: In 1893 Buffalo Bill brought the Wild West home from Europe for the first time in five years, to the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. He hadn’t been forgotten: Americans had been reading about his travels, the royal accolades, about the shows in Paris, Rome and Berlin. None of that mattered to the Exposition’s high-minded managers: the show was deemed too crass and was excluded from the grounds.

The Exposition was a grandiose celebration of white civilization in America. Its centerpiece — the White City — perfectly captured the spirit of the fair. It might have been another planet to the people who lived and worked in Chicago’s dark and crowded streets. Cody’s version of the American story spoke to them. He ignored the Exposition’s managers, and set up shop across the street. 3,000,000 people saw the Wild West that summer, and Cody walked away with over half a million dollars. He still had that innate feel for his audience, especially the immigrants who were transforming the country.

Bobby Bridger, Writer: On the street you had newsboys barking dime novels: “Buffalo Bill, Buffalo Bill.” And then you had people pouring into America by the droves at that point with no idea what it meant to be an American. And so on the street you had these little newsboys here’s what an American is you see. This is an American.

Louis Warren, Biographer: Americans, up to the 1890s, it’s really the Puritans that they looked to as the founders of this thing that becomes the United States of America. Cody takes American history, situates it somewhere in this frontier west, and says this is your story. In searching to broaden his story for that public so he can draw them in and make money he actually changes the telling of American history. It’s that search for bigger audiences as much as anything else that has driven the, the changes in how we tell American history.

Narrator: On a hot and sunny July afternoon, a group of historians took a break from a conference they were attending at the Exposition and headed across the street to the Wild West. One of their colleagues, a young historian named Frederick Jackson Turner, stayed behind to work on a presentation for the evening session. When the historians returned from Cody’s celebration of the frontier, they heard Turner announce its passing. “Four centuries from the discovery of America the frontier has gone,” he said, “and with its going has closed the first period of American history.” The West of Cody’s youth had slipped out of reach: where his earliest shows had been like newsreels from the frontier, now he was commemorating scenes from a receding past.

Patricia Nelson Limerick, Historian: So it’s a mournful occasion in many ways. But it somehow or other manages to stay cheerful even though this exciting era that what made us a distinctive people has just ended. Somehow that works, elegy and celebration in the same package.

Narrator: Shortly after the glittering season in Chicago, Nate Salsbury contracted a disease that slowly paralyzed him. He gave up the management of the show and drifted away from Cody. His steadying hand would be missed. His death in 1902 marked a turning point in Cody’s fortunes.

A few months after Salsbury’s death, Cody wrote to his sister: “Divorces are not looked down upon now as they used to be — people are getting more enlightened. I will give her every bit of the North Platte property and an annual income if she will give me a quiet legal separation.”

Louisa wasn’t going anywhere quietly. After Cody filed for divorce, she threatened to bring him down “so low the dogs won’t bark at you.” Cody was sure that the public’s adulation would insulate him. For once, he misjudged his audience.

Charles Scoggin, Writer: There’s a prolonged trial. Lots of depositions. Things come out about Cody’s behavior that aren’t all that flattering. His relationship with other women is exposed, one of which is Bessie Isbell, who was his publicity agent. In the course of the trial Cody admitted that he had bought a ranch and conveyed title to Isbell for one dollar and other considerations. And when asked what the other considerations were Cody said I don’t remember.

Narrator: The press had helped create Buffalo Bill; now it fed on him. He was a drunkard, a philanderer, a blasphemer. At the end of the ordeal the judge rejected Cody’s suit: he was bound to Louisa.

Cody fled again, this time to rejoin the Wild West in Paris. His fame had turned on him. “I do not want to die a showman,” he wrote, “I grow very tired of this sort of sham hero-worship sometimes.” He dreamed of a peaceful retirement but he had a habit of spending more than he earned. In 1910 alone he made $200,000, and could have retired then and there. Instead, he squandered it on a gold mine swindle in Arizona. Cody couldn’t seem to pass up a bad idea.

Charles Scoggin, Writer: He’s investing in printing companies and gold milling companies; a company that’s making a coffee substitute for the Mormons; livery stables; a car service into Yellowstone; a military boys school in Wyoming; the Cody oil fields, and he just got taken to the cleaners.

Narrator: After forty years of show business, the sixty-five year old Cody was looking for a way out: out of debt, out of the endless grind of travel and performances.

Charles Scoggin, Writer: “St. Louis, October 5th 1911. Dear pard. Your telegram just came. It found me sick and working in rain and mud. The doctors tell me I’m running a fearful risk and I know it. But although we are doing no business I should miss a performance and newspapers would take it up and no one would come. Heaven knows we are losing enough as it is. I’ve never been so discouraged.”

Narrator: It was only getting harder: more and more of his audience was going to the movies, including the dozens of Westerns on offer. Cody decided to bet everything on a plan to produce a movie himself — a film about the Indian Wars. He borrowed heavily, called on his old army connections to supply the troops, and got one last performance out of his old Sioux friends at Wounded Knee. But for all that, Cody just didn’t know how to make a film: it looked like a Wild West show, seen from a distance.

Louis Warren, Biographer: Directors and producers hit on this idea we can focus on individuals, we can make their faces look so large on the screen that you can see their emotions. And it becomes a very different kind of story from the Wild West spectacular.

Juti Winchester, Historian: When the show went bankrupt in 1913 that was the beginning of the end. One of the people that was involved in the bankruptcy was Henry Tammen; who was the owner of the Denver Post. And Tammen also owned the Sells-Floto circus, and as partial payment for this debt he put Cody in the circus and exhibited him as Buffalo Bill. And traveled with him around the country, a grueling, grueling schedule.

Narrator: Cody never did find a way out; he was a showman to the end. But in his last years he did find some of the tranquility that had eluded him ever since his childhood in Kansas. Six years after the divorce trial, forty-five years after they were married, the Codys’ only surviving daughter contrived to leave the couple alone in a room together. By the time they emerged Louisa Cody and her roving plainsman had finally made peace.

Juti Winchester, Historian: I don’t think Louisa ever stopped loving Will Cody. And she traveled with him during these really difficult years. And one of the interesting things is, if you look at old photographs in the early days he’s always wearing a large gold, horseshoe shaped watch fob. It’s one of the few things you always see on him. After their reconciliation, she’s wearing it as a necklace. Louisa has it as a necklace. And after his death she’s still wearing it. It’s, it’s one of those talismans of their relationship that she never let go of it.

Narrator: Cody’s life was hard, but he had Louisa, he was sober, and he had found a quiet faith in the same place he had found everything else: “I believe that a man gets closer to God out there in the big, free West,” he wrote, “You are filled with a true religion and a bigger realization of life.”

Cody’s nephew remembered his last hours: “He would imagine that he was on the road with his show and ask me where we were and what time it was and when we got in. In fact he lived his life over again. He done just as he did when he was on the road with the show.” William Cody died quietly at his sister’s home in Denver on January 10, 1917.

Twenty-five thousand people lined up to pay their respects. Tributes flooded in from the King of England, President Wilson, generals, old colleagues, and ordinary people who had seen him in the Wild West decades before. Among the messages was a note to his family from Pine Ridge, South Dakota.

Guy Dull Knife, Grandson of George Dull Knife: “The Oglala Sioux Indians of Pine Ridge, South Dakota resolve that deepest sympathy be extended to the wife, relatives and friends of the late William F. Cody for the loss they have suffered. These people who have endured may know that the Oglalas found in Buffalo Bill a warm and lasting friend.”

Narrator: The frontier had vanished, the buffalo were gone, the Indians Wars had ended, America had been transformed by industry and waves of immigration; the civilization Cody had championed was dying in the carnage of the Western Front. But the myth of the American frontier remained, and William Cody — Buffalo Bill — would forever be part of that story.

Louis Warren, Biographer: Even the people who didn’t see him heard so much about him. His story was so alluring, this wide-open frontier that he came from where there were no elites to tax you, where there was nobody to make you work for them. That story was such a great story and they could attach it to him. I think we’re still — we’re still in love with that story, and we still need it.