Narrator: In 1931, there was no better place to be a farmer than the Southern Plains. The rest of the nation was in the grip of the Great Depression, but in wheat country they were reaping a record-breaking crop.

Plains farmers had turned untamed prairie into one of the most prosperous regions in the country.

Lawrence Svobida (Matthew Modine, voice over): I came to Meade County, Kansas fired with ambition to become a wheat farmer.

Narrator: Lawrence Svobida had come from Nebraska’s Corn Belt to start his own farm. He was one of those who believed he had found paradise.

Lawrence Svobida (Matthew Modine, voice over): Harvesting wheat was a thrill to me. The roar of the laboring motors and the whine of the combine was music to my ears.

It was breath-taking — hundreds of acres of wheat that were mine. To me it was the most beautiful scene in all the world.

Narrator: At the turn of the century, when settlers gazed upon the Southern Plains, they had looked out over a vast expanse of shrubs and grasses. The land was green and lush, and the soil so rich, an observer noted, that it “looked like chocolate where the plow turned the sod.”

The newcomers did not realize that they were witnessing only a brief moment in an endless cycle of rain and drought.

Yet boosters and promoters lured in farmers with the promise of heaven on earth.

Pamela Riney-Kehrberg, historian: You had railroad companies and states putting out advertisements encouraging people to think of this land as a bountiful land. The State of Kansas put out posters showing watermelons the size of small automobiles, grapes the size of bowling balls, corn that you had to pick by going up a ladder, and people were encouraged to believe that this was the Garden of Eden if they would only have the courage to go out and challenge the land.

Narrator: Thousands of eager settlers took up the challenge, bringing farming techniques that had worked well in the Northeast. Confident of rain, unmindful of wind, they plowed mile after mile of virgin sod.

With the outbreak of WWI, Washington wanted wheat — wheat would win the war! With record high prices, the promise of the land was coming true. Millions of acres of grassland would feel the plow for the first time. The race was on to turn every inch of the Southern Plains into profit.

Appearing like giant armored bugs creeping along the horizon, tractors came to the fields in the 1920’s. With a team of horses, a farmer could barely turn three acres of prairie sod in a day. With a tractor, he could plow 50. The Great Plow-Up was under way.

J.R. Davison, Texhoma, Oklahoma: So everybody got him a John Deere tractor or an old International and really went to plowin’ this country and my dad was no different than the rest of 'em. You know, he’d run that thing all day and when the sun went down, why, he’d come in and do the chores and I’d go runnin’ that tractor 'til morning.

Dad would work it in the daytime. He’d have everything serviced, plow greased, everything ready to go. When I got my turn all I had to do was just get on there and drive that thing.

Narrator: With so much bounty flowing from the Southern Plains, outsiders saw an opportunity to make a killing and began speculating on wheat. “Suitcase Farmers,” they were called — eastern bankers, businessmen, lawyers — who put in their seed and went home till harvest season.

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: It produced good. It looked like the greatest thing would never end. So they abused the land. They abused it somethin’ terrible. They raped it. They got everything out they could.

And we don’t think. We don’t think. Except for ourselves and it comes down to greed. We’re selfish and we want what we want and we don’t even think of what the end results might be.

J.R. Davison, Texhoma, Oklahoma: I think that most of those people thought this is just what we might say 'hog heaven’. It’ll always be this way. So they kept breaking this country out and they plowed up a lot of country that should never have been plowed up. They got the whole country plowed up nearly and, ah, that’s about the time it turned off terribly dry.

Narrator: Whirlwinds had always danced across the fields on hot, dry, days. No one took much notice that these swirls of dust were growing thicker, taller, and faster than usual.

Then in the summer of 1931, the rains stopped. Wheat withered in the fields — leaving the land naked and vulnerable to the menacing winds. But, no one was prepared for what was to come.

Lawrence Svobida (Matthew Modine, voice over): The winds unleashed their fury with a force beyond my wildest imagination. It blew continuously for a hundred hours and it seemed as if the whole surface of the earth would be blown away.

As far as my eyes could see, my fields were completely bare.

Narrator: As dust enveloped the atmosphere, it got into the eyes, the nose, the mouth — breathing became difficult. The Red Cross issued an urgent call for dust masks, especially for children.

Floyd Coen, Elkhart, Kansas: So we’d wear face masks in school, and — and, ah, during our work and so forth, it’d be a gauze mask that — and you could never seem to get a real good breath from that. And you often wondered, will I get enough oxygen to my system? Will this be damaging?

Narrator: Residents grabbed any bits of cloth to cover their faces. The Plains began to resemble a WWI battlefield, with dust rather than mustard gas fouling the air.

Where grain once grew high as a man’s shoulder, dazed farmers walked out over their beaten, blown-out fields.

It had taken a thousand years to build an inch of topsoil on the Southern Plains. It took only minutes for one good blow to sweep it all away.

Imogene Glover, Guymon, Oklahoma: Well, after a dirt storm the ground would just be bare where it had blown all the topsoil away and then it would be mounds over where the fence rows had been. So we didn’t have much except just bare old hard ground. It was a bad time.

Narrator: One hundred million acres of the Southern Plains were turning into a wasteland. A circle encompassing large sections of five states in the nation’s heartland: the Panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma, western Kansas, and the eastern portions of Colorado and New Mexico.

A journalist traveling through the region called it the Dust Bowl.

Judge Wilson Cowen, Dalhart, Texas: The farmhouses looked terrible—the dust was deposited clear up to the window sills in these farmhouses, clear up to the window sills. And even about half of the front door was blocked by this sand. And if people inside wanted to get out, they had to climb out through the window to get out with a shovel to shovel out the front door. And, ah, there was no longer any yard at all there, not a green sprig, not a living thing of any kind, not even a field mouse. Nothing.

Narrator: Convinced that the storms were a freak accident, that the rains would soon return, residents could not imagine that they had entered a battle that would last a decade.

Margie Daniels, Hooker, Oklahoma: The next morning you’d still have that dust settling in the air, but there would be the sunshine and all again but then everything would just be covered in dirt. Everything was full of dust. If you were cooking a meal, you’d end up with dust in your food and you would feel it in your teeth. You’d start to eat and when you would drink water or something, you would grit down and you always felt like you had grit between your teeth. You know it felt terrible.

Clella Schmidt, Spearman, Texas: The next day when Mother and my grandmother started cleaning out the house, they were taking the dirt out in buckets full. They were scooping it up onto, ah, ah, wheat scoops, which are pretty good-sized scoops, and carrying it out into the yard.

Imogene Glover, Guymon, Oklahoma: The dust was just like face powder. It was so heavy and thick. It wasn’t like sand. It was just real heavy, like face powder. Only it was real dark, almost black.

Narrator: To the astonishment of residents, the dust kept coming. In 1932, the weather bureau reported 14 dust storms. The next year, the number climbed to 38.

People tried to protect themselves by hanging wet sheets in front of doorways and windows to filter the dirt. They stuffed window frames with gummed tape and rags. But keeping the fine particles out was impossible. The dust permeated the tiniest cracks and crevices.

Imogene Glover, Guymon, Oklahoma: We just had a lot of dirt. (Laughs) I just grew up with it. I thought that was what life was all about.

Narrator: The drought persisted, made worse by some of the hottest summers on record. Windmills provided drinking water from deep wells, but the fields were bone dry.

Still confident that the rains would return, farmers continued to plow. “Out of this blast of dust,” one observer wrote, “the men of Western Kansas whistle and go right on sowing wheat.”

Lorene White, Manter, Kansas: If dad was in the field we were always afraid, you know. We didn’t know whether dad could get in or not because the dust was so bad. Dad always had a tendency, like most men did, I guess, they would stay in the field until it — the storm got there. So Mom and we kids, we were at home watching, waiting for Dad to come in, thinking he would surely come before the dirt hit, and usually he didn’t. And, ah, then we’d have to worry about him getting in. And I, worry was part of my make up, so I — I worried about him.

Narrator: 1934. The storms were coming with alarming frequency. Residents believed they could pinpoint a storm’s origins by the color of the dust — black from Kansas, red from Oklahoma, gray from Colorado or New Mexico.

As the storms rampaged across the land, they unleashed another destructive force.

J.R.Davison, Texhoma, Oklahoma: I can remember when Dad had a good wheat crop growing and it blew terribly hard for two days. At the end of that two days, static electricity, the electricity in the air, had completely killed the wheat crop. All of that green wheat had just turned brown and was dead.

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: I had a little garden and I had me some watermelons and I’d carry water by the bucket out and water it. And I remember I went out that evenin’ to water 'em and I had some little watermelons about as long as your little finger, just as pretty and shiny, a little fuzz on 'em, you know? And went out the next mornin’ after one of them sand storms and there are the watermelons’ vines whipped around and them little melons just black as tar. It was completely just because of static electricity and that continuous wind.

Narrator: For farmers it was going on three years of planting with little to show for it. The hard times were beginning to take their toll.

Margie Daniels, Hooker, Oklahoma: I can remember looking at Dad and he’d be laid back in his big chair, his old lounge chair, you know, with his feet up and usually one of the kids on his lap. But he would just be, you know, kinda lookin’ off into space or something. You could tell. You could tell by his attitude if he was depressed.

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: My mother, she’d be walkin’ the floor and when she got nearly cryin’, her chin would draw up, you know, and she’d wring her hands and say, “Oh, the wind, the wind, the wind.” And she’d just cry, because she realized the conditions things was in. I didn’t. I just thought, “Well, it’s dry and the wind’s blowin’ and the sand’s blowin’.” But she realized how Dad was havin’ to work, what little he was makin’, and we’as about to starve to death.

Imogene Glover, Guymon, Oklahoma: We had meager food at that time. Everyone did. And we lived literally on cornbread and beans. And that was our main meal and at night we’d just have cornbread and milk, but so did everybody else. In fact, I felt like we had good food compared to a lot of people.

Narrator: Outside the Southern Plains, few grasped the full measure of the disaster. In Washington, the Dust Bowl was seen as just another trouble spot in the nationwide crisis of the Depression. The government began offering relief through Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Lorene White, Manter, Kansas: My Dad was really proud. He thought it was charity to take help from the government, and for a long time, he wouldn’t. Even when government programs came in, you know, in relation to his farming, where he could have been paid for certain farming practices, there was quite a while that Dad wouldn’t do it.

Narrator: The sturdy people who settled this country were not “leaners,” residents insisted. Yet most had no choice but to suffer the humiliation of relief checks and food hand-outs.

Lorene White, Manter, Kansas: There was a time when there was canned food that was available to people who were in the situation that we were. We were poor I guess. We didn’t call ourselves poor but I guess we were. But Dad wouldn’t, he wouldn’t let Mom get it.

I think Dad would have let us eat pretty poorly before he would have accepted any help. He was, he thought he was, that it was his job. He was the breadwinner of the family, and it was a disgrace for him to let someone else come in and take care of his family, and he felt like that’s what was happening.

Narrator: Piece by piece, farmers were losing everything they cherished.

In the fall of 1934, with livestock feed depleted, the government began to buy and destroy thousands of starving cattle.

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: Each and everyday got worse and you couldn’t see no end, and you couldn’t see anything of any improvement. And the government come in and took the cattle and killed 'em, paid $16 for a cow and $3 dollars for a calf. When that was gone, you didn’t have anything hardly left.

Narrator: Of all the government programs, cattle slaughter would be the most wrenching.

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: Well, that cow, you’d milked her. See her big ol’ kind eyes and she furnished you milk and food and — and to see 'em just take and lead her off and you knew that’as the end of her, that’as the end of her life, well, when was yours comin’, you know? It was pretty sad.

Narrator: With the Southern Plains becoming more desert-like with each passing month, residents themselves were beginning to wonder whether the only difference between the Dust Bowl and the Sahara Desert was that a lot of “dammed fools” were not trying to farm the sands of North Africa.

Lawrence Svobida (Matthew Modine, voice over): I believe any man must see the beauty in mile upon mile of level land where the wheat is waist high, sways to the slightest breeze and is turning a golden yellow under a flaming sun.

It was evening when a huge bank of dark rain clouds formed in the northwest. As the storm approached… I could feel its coolness, smell it — almost taste it

I waited in suspense, looking, hoping—praying for rain. But the rain did not come.

Narrator: 1935. After years of drought and dust, the land was now being destroyed by another kind of plague. Hundreds of thousands of starving jack rabbits came down from the hills, devouring everything in their path.

Dust Bowlers were forced to begin an extermination campaign. Almost every Sunday people gathered to take part in rabbit drives.

J.R.Davison, Texhoma, Oklahoma: When we first came over the — the hill there on this one drive, there were big line of us. Just looked like the country below us just all began to move. Looked like a herd of sheep, but it was jackrabbits.

The first rabbit drive that I ever witnessed was with shotguns, but that was kind of dangerous, so then they decided later that they’d have some more of these rabbit drives, and we’d just use clubs. So they would form lines of people, and these lines of people would march down through that country and come together, and funnel these rabbits into those pens, and any that tried to get back by you, which would be a lot of `em, why you were supposed to knock them in the head with the club as they came by.

And then after they got them all in these pens, why, the young fellows would get in those pens with these clubs, which was like an old axe handle or something like this, and — and just club them to death. I can imagine, you know, what the Humane Society would say about that now. Whew.

Margie Daniels, Hooker, Oklahoma: You could hear the rabbits screaming you know. That’s what was scary to me. I think that sound affected everyone. I know it sounded terrible to me as a little girl. And you know I’d think sounds like a baby cryin’ or squealin’, or, you know, being hurt. It was really sad.

And then this dirt storm was coming in at that time. And it was starting to get dark. And you know, some people felt that was the wrath of God coming upon them when they’d kill these rabbits like this.

Narrator: April 14, 1935 was the worst day of them all. The day no Dust Bowler would forget. The day they would call “Black Sunday.”

Margie Daniels, Hooker, Oklahoma: Everybody tried to get out of there. Everybody was scrambling to get out to their vehicles and find their families. It looked real black as it came in just big old rolls just coming in.

As the dark clouds approached, there was an ominous silence. Minutes later, the stillness was shattered by thousands of birds fleeing before the avalanche of dirt.

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: And back in the north it’as just a little bank, oh, like about eight or ten feet high. It had one of those headers out on each end, you know. And I did a few things there around the chickens and everything and went back in the house and I said, “Dad, we ain’t goin’ to be able to go to church tonight.” And he, “Why?” And (Phew) that’s how fast it’s travelin’.

J.R. Davison, Texhoma, Oklahoma: My dad went into the kitchen when that dirt was blowing the hardest. The wind was really whippin’. And I can remember my dad goin’ in there and takin’ hold of those two-by-fours and his hands would move up and down five or six inches, this wind was whipping so hard. And I thought to myself, “This thing may blow away.”

Margie Daniels, Hooker, Oklahoma: When the storm hit, my father just grabbed us. I remember Daddy takin’ me and he set us right by the car and he said, “Stay there! Don’t move.” Well, I wasn’t about to move. And so then the neighbor man was cryin’ and his family was all crying. And so Daddy went over and tried to help 'em and he was stickin’ his hankie in the radiator, you know, and puttin’ it on his face. And he’d say, “Oh, God, we’re gonna die.” He said, “We’re all gonna die.” And Daddy finally just said, “Hush. You help me take care of these kids.” That’s when he told him he said, “You get your family in your car and I will bumper you home.”

Narrator: Terrified residents tried to drive through blinding dust. One Kansas farmer, disoriented, drove his car off the road. Searchers found him the next day, suffocated.

Clella Schmidt, Spearman, Texas: My dad thought that we should stop and pick up this neighbor and her baby and it hit just about the time we were getting out of the car to go into the house. And this woman was hysterical. She was she thought she should maybe just go ahead and kill the baby and herself because it was the end of the world and she didn’t want to face it alone. And so my dad quoted Bible scriptures to her to prove that it was not yet time for the end of the world, that he had no idea what this was, but it was certainly not the end of the world!

Narrator: After Black Sunday, others turning to the Bible found support for their worst fears. “The Lord shall make the rain of thy land powder and dust”, they read, “from heaven it shall come down upon thee, until thou be destroyed.”

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: In the spring of 1935, the wind blew 27 days and nights without quittin’, and I remember that’s why my mother just — I thought she was going to go crazy because it was just — it was — you got desperate, because if the wind blew durin’ the day or durin’ the night and let up, you got some relief. But just day and night, 24 hours, one 24-hour after the other, it just — but it’s 27 days and nights in the spring of 1935 it didn’t let up.

Narrator: Living on the Plains was becoming an act of sheer will.

The dust was beginning to make living things sick. Animals were found dead in the fields. Their stomachs coated with two inches of dirt. People spat up clods of dirt, sometimes three to four inches long and as big around as a pencil. An epidemic raged throughout the Plains. They called it dust pneumonia. Many residents tried their own home remedies.

Floyd Coen, Elkhart, Kansas: Skunk grease. We had a — a neighbor that trapped skunks and he would save the fat and render it out and — and supposedly that skunk grease was skunk oil was, penetrate your chest better, but we never, we never liked to use it.

Imogene Glover, Guymon, Oklahoma: Mother would give us sugar with a drop of coal oil on it or a drop of turpentine. And this would clear the phlegm out of our throats.

Lorene White, Manter, Kansas: Mom would mix, ah, kerosene and lard, and, ah, nowadays we have Crisco, but then we had lard, you know, and she would mix those together. I supposed it would have blistered if they hadn’t used lard in it, but she’d rub our throats, oh, we’d be covered with it, and I hated it because it would stink so.

Narrator: In 1935, one-third of the deaths in Ford County, Kansas, resulted from pneumonia. Children were especially vulnerable.

J.R. Davison, Texhoma, Oklahoma: I guess I was sicker than I ever realized, because I got, ah delirious. I was out of my head. I can see, to this day, those merry go round horses coming out of the ceiling, you know? They’d just, like this, just like a merry go horse — round horse goes. And I’d say, mom? She was always there by my bed, seemed like. I’d say, mom? Those horses are gonna hit you, said, you better move your head. And she’d move her head over. Say, boy, that one like to got you. And so I don’t really know how sick I was, but I was pretty sick. I think she thought a time or two I wasn’t gonna make it.

Margie Daniels, Hooker, Oklahoma: I had a little brother that had pneumonia three times. And I’ve always felt it was caused from too much dirt. I remember Mother, ah, took — gave him his medicine in the spoon. I stayed in the room with her to — because we had to sit up with him all night. And she put this medicine in a spoon and put it in his mouth and he … he swallowed it and laid back in her arms and died. (Crying) Excuse me. But I’ll never forget how that affected my mother. She started screaming and she just held him so tight. And even though she had several children, you know, you have people say, “Well, you have several children. If you lose one, it won’t matter.” That’s not true because this affected Mother in a way that, ah, she was never the same again.

I cried myself to sleep, I think, every night for a year, ah, because of losing him. But I think the worst thing about that was that I was the one that brought the measles home to him. You know, I was in school and I took the measles and I came home with 'em and if he hadn’t got the measles, he would have, he might have come out of it. But they said pneumonia and measles, they never did.

Narrator: By the end of 1935, with no substantial rainfall in four years, some residents were giving up.

Dust Bowlers watched as their neighbors and friends picked up and headed west in search of farm jobs in California. Having packed their meager belongings, they did not even bother to shut the door behind them — they just drove away, their eyes fixed on the uncertain road before them.

Judge Wilson Cowen, Dalhart, Texas: Many of them came by the courthouse. And they’d come by and see me and say, “Judge, you know, we’ve reached the end of our rope. We don’t have anything left. We’ve got to get out of here.” And then say to me, “You know, we need a second hand tire pretty bad.” Of course, I always signed orders authorizing the local filling stations to get them a cheap second hand tire. Cost about three dollars and a half. And a tank full of gasoline. And they were very pleased about it.

But I’ll tell you, they were gaunt, tired-looking people. I felt very sorry for 'em. The whole family, the wife, the kids and the husband, they were tired-lookin’ people, people that you could see felt rather hopeless.

Narrator: Throughout the country, word spread of a mass exodus from the Plains. In all, a quarter of the population would flee the region.

Imogene Glover, Guymon, Oklahoma: We hated to see anyone leave. There were so few close neighbors or close friends or relatives. And we hated for 'em to leave, but we all told 'em to be sure and write us from California. We were all afraid we would never see 'em again, you know when everyone was leaving the Panhandle.

Lorene White, Manter, Kansas: Lots of people left. The family west of us left, and they had kids that we played with. Ah, there was a family, two families, east of us, that left. Ah, one of the ones, one of the families was the one where the man died, young man died, with the dust pneumonia. And they moved away.

Narrator: As people abandoned the Southern Plains, tight-knit rural communities began to unravel. Banks and businesses failed. Schools shut their doors. Churches were boarded up.

Yet, even with the world crumbling around them, most Dust Bowlers chose to stay.

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: Dad always lived with hope, see, “Next year. Next year. I failed this time, but next year’ll be better.” And I never did see him have the look of givin’ up or quitting. He always stayed in there and seemed that he was gonna make it some way or another. If anybody made it, he’d be one of 'em, he thought.

Narrator: No one understood the tenacity of Plains farmers better than John McCarty, the editor of the Dalhart Texan newspaper.

Judge Wilson Cowen, Dalhart, Texas: John McCarty was a great booster. He was always saying that “One of these days the rains will come again and this land will bloom like a rose.” And he was good at getting that message across.

Narrator: A week after the infamous “Black Sunday,” McCarty created the Last Man’s Club. Urging Dust Bowlers to “grab a root and growl,” the young editor issued a call to arms.

Judge Wilson Cowen, Dalhart, Texas: The Last Man’s Club was one of John McCarty’s efforts to build up courage in the minds of the people. All of us who joined, I think my number was 31 — ah, we all had to sign a pledge. And the pledge went something like this. Ah, “In the absence of an act of God, serious family injury or some or other emergency, I pledge to stay here as the last man and to do everything I can to help other last men remain in this country.

John McCarty (archival): In states north of here people are moving out by the thousands. Well we’re not quitting. Non-resident land is vicious land. Are we gonna stay here till hell freezes over? (Cheer.)

Floyd Coen, Elkhart, Kansas: My father would often say, “Why would I go somewhere else? Everything I have is here. And it’s gonna—it’s gonna be better.” I’ve heard him say so many times, “It’s gonna be better.”

Narrator: On the outskirts of Amarillo, Texas, townspeople discovered a crow’s nest made entirely of barbed wire — the only material the birds could scavenge from the lifeless terrain. Anything that could was stubbornly holding on.

Narrator: On the parched Texas landscape, explosives expert Tex Thornton, proposed a novel solution to the region’s woes. Explosions, he claimed, would excite the atmosphere and induce rain. Desperate to end the drought, a group of farmers and businessmen hired Thornton, giving him $300 to buy nitro-glycerine and TNT.

Judge Wilson Cowen, Dalhart, Texas: He advertised himself as a rainmaker and a few of the people in town believed it might help. I didn’t think that you could make rain that way. But of course, I had to admit I didn’t know. And like other people I hoped maybe something good would happen that we’d get some rain.

Well, he tried two or three times and one of the queer results about it, the—just a little bit following his last try, they had quite a bit of snow. Not very much, but it was in May so it was quite unusual. There might have been, oh, maybe two or three inches at the most. And he got a lot of credit for that. Some of the people who had espoused his work thought that “Really we’re ending the drought here,” but, of course, that was illusory. It didn’t happen.

Lawrence Svobida (Matthew Modine, voice over): The summer of ’36 was one of the hottest ever. Hundreds of square miles of bare fields absorbed the suns rays like fire brick in a kiln. The wind was like a blast from a huge, red-hot furnace—causing my face to blister and peel off. Perhaps I was learning stoicism, but I found myself hardening to disaster.

Narrator: As the drought wore on, there were some who claimed that Plains farmers themselves held the key to their own survival.

Hugh Bennett (archival): We Americans have been the greatest destroyers of land of any race or people, barbaric or civilized.

Narrator: Known as the father of soil conservation, Hugh Bennett was the leader of a new breed of agricultural experts. He argued that conservation techniques could restore farming to the Southern Plains.

Bennett took his case to lawmakers on Capitol Hill. As he was about to testify, he learned that a great dust storm was heading towards the east coast. The storm had already deposited 12 million pounds of dust on Chicago — four pounds for each person in the city — and was poised to descend on the nation’s capital. Bennett used every stalling tactic he could, managing to keep the committee in session until the dark gloom settled on Washington. “This, gentleman,” he announced, “is what I have been talking about.” For the first time Easterners smelled, breathed, and tasted the dust blowing off the Southern Plains.

For years — before the dust storms — the Federal government had regarded the soil as a limitless, indestructible resource. In a major shift, Washington now put its full weight and authority behind soil conservation. To promote the new message, the administration produced a provocative film about the causes of the Dust Bowl. Filmed near Dalhart, Texas, the filmmakers searched for a local farmer to play the part of an original settler. They found Bam White, Melt White’s father.

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: They was wantin’ someone with a team and a plow to more or less demonstrate how they started breakin’ the plains up. So him, with a team, just two horses, a single team, and a one-bottom breakin’ plow, that way they could take and show that and have him let the plow go in the ground and start turnin’ over sod, grassland that had never been broken up. So they come to him. And I know he put on his best hat and he left about 8 or 8:30 that morning. And got back a little after eleven.

And you never saw such a happy man in your life. He said, “They paid me $25 for two hours’ work.” He said, “That’s nearly a month’s wages and I don’t see how they can afford to pay wages like that.” He had no idea what it was all about, who they were, or what they was gonna make of it.

Film Narrator (archival): “High winds and sun. High winds and sun. A country without rivers and with little rain. Settler, plow at your peril.”

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: So they had him bein’ the guilty one to start it, (laughs) of bein’ the one that started breakin’ the plains out back in the early day.

Film Narrator (archival): “100 million acres, 200 million acres, more wheat…”

Narrator: In 1936, the completed film was released across the country — and in Dalhart at the Mission Theater.

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: Then directly there dad went to goin’ across the screen up there, him and ol’ Tom and Ann’s the name of the horses. There he was a-plowin’ and here he was sittin’ here by me and I’d lookin’ at him lookin’ there and I couldn’t figure out how they was doin’ that, showin’ him that real. Him and the horses was bein’ shown and here he sat here by me. So it was quite a thing and that’s the first movie I ever saw in my life.

Film Narrator (archival): “Last year in every summer month 30,000 people left the Great Plains and hit the highways for the Pacific coast, the last border.”

Narrator: Panicked by the flood of penniless refugees heading to the west coast, a government report warned that “for its own sake, the nation cannot allow farmers to fail.”

In 1937, Washington began an aggressive campaign to encourage Dust Bowlers to adopt planting and plowing methods that conserve the soil. But getting the farmers of the Southern Plains to change their ways would not be easy.

J.R. Davison, Texhoma, Oklahoma: They came out with a lot of these methods, but most of these old-timers wouldn’t do it. You know, finally they got where they’ad pay 'em. You know, you could make a dollar an acre if you practiced one of these methods. And that got a lot of 'em workin’ on it because they needed that dollar an acre.

Narrator: Once again farmers ran their tractors from dawn to dark. This time to prevent barren fields from blowing.

Lawrence Svobida (Matthew Modine, voice over): I felt I was becoming a slave to the land. But I held on to the thought that this land had to be stopped from blowing. Often I was so full of dust that I drove blind, unable to see even the radiator cap on my tractor or hear the roar of the engines. But I kept driving on and on, by guess and instinct.

I was making my last stand in the dust bowl.

Narrator: 1938. The massive conservation crusade had reduced the amount of blowing soil by 65 percent. But the drought dragged on. The parched land refused to yield a decent living. The proud settlers of the Plains were becoming dependent on government work projects for survival.

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: Dad he’d get up in the mornin’ and feed the horses and harness the team, hitch 'em, and go to work. And, ah, work for the WPA. Drove the team. He got a dollar-and-thirty-five-cents a day, him, team, and wagon. And, ah, that was — that was it.

On the weekend, say, on a Sunday we’d try to get him to play the fiddle. Well, when he was workin’ on the WPA haulin’ cleechy, his hands would be cracked from that cleechy. That alkali would just crack his hands and he’d get that old fiddle out and it makes tears in my eyes now to think he’d sit and play it with blood runnin’ out his fingers just for our entertainment.

Lawrence Svobida (Matthew Modine, voice over): Preachers teach the blessings of adversity, but I now believe too much adversity breaks a person down. Season after season I had worked incessantly to keep my land from blowing, and no effort of mine had proved fruitful. Words are useless to describe the experience when the thin thread of faith snaps. My youth and ambition were ground into the very dust itself. I was finally ready to admit defeat.

Narrator: In the spring of 1939, after the failure of seven wheat crops in eight years, Lawrence Svobida abandoned his farm and fled — convinced that the Dust Bowl was creating an American Sahara.

Six months later, the skies finally opened. Nearly a decade of dirt and dust was coming to an end.

Floyd Coen, Elkhart, Kansas: When the rain came, it meant life itself. It meant a future. It meant that there would be something better ahead of you. And we as young people, and sometimes parents, you’d go out in that rain and just feel that rain hit your face. It was a very emotional time when you’d get rain because it meant so much to you. You didn’t have false hope any more, you knew then that you was going to have some crops.

Melt White, Dalhart, Texas: There’d be lightning back in the Northwest, you’d see flickering lightning and Dad would say, “That’ll be in here about 2 o’clock in the morning.” But the rain was so welcome and they smelt so good I’d lay and listen to them pitter patter on the side of the old house at night and we’d really sleep. Cause it was a wonderful feeling.

Narrator: With the return of the rain, dry fields soon overflowed with golden wheat. The harsh years of the Dust Bowl had forced farmers to accept the limits of the land. But with fortunes to be made once more on the Southern Plains, that wisdom would soon be tested.

In western Kansas, a group of farmers gathered on the steps of the local courthouse. One was hopeful about the future. “People are thinking differently about taking care of the land,” he said. “Don’t fool yourself,” another replied. “You can’t convince me we’ve learned our lesson. It’s just not in our blood to play a safe game.”

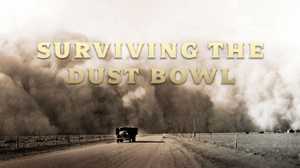

Surviving the Dust Bowl

Surviving the Dust Bowl