NARRATOR: They came from nothing yet each did what he had to survive.

TRUMAN GIBSON, Joe Louis Attorney: Nobody knew how deeply Joe really felt, at an early age he learned to suppress emotions. He never really showed them.

GEORGE von der Lippe, Professor, St. Anselm College: If I had a theme for Max's life, it would be that he's a survivor. He adapts to the situation, he adapts to the people he's dealing with.

JEFFREY SAMMONS, Historian: He could not gloat over opponents. He could not be seen in public with white women. He had to be seen as a Bible reading, mother loving, god fearing, individual, and not to be too black.

VOLKER KLUGE, Sports Journalist: He was loyal to his government. But this loyalty had a high price. He had to burden his conscience with the dark sides of the regime.

NARRATOR: When they met in the ring, they were the reluctant symbols of their people...

VERNON JARRETT, Writer: We invested so much in Joe Louis ... He was our nonviolent, violent way of expressing ourselves.

NARRATOR: --and of their nations, in the shadow of war.

JACK NEWFIELD, Writer: as Joe Louis found himself drafted to be the symbol of democracy and America, Schmeling found himself conscripted to be the symbol of Aryan supremacy... they were prisoners of politics.

NARRATOR: They would fight only twice, but their rivalry would captivate the world; and by the time they were done, no one would ever forget them.

DAVID: They were like Lewis and Clark or Sacco and Vanzetti. History brought Joe Louis and Max Schmeling together and in history they'll always be together.

"THE FIGHT"

RADIO ANNOUNCER (archival): The Studebaker Corporation featuring Richard Himmler and his Studebaker Champs usually heard at this time over some of these stations is courteously relinquishing as much of their program as will be necessary in order that a special program may be presented.

FIGHT ANNOUNCER (archival): Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. This is Howard Planey speaking and in a moment we will present a ringside blow-by-blow description of the Louis-Schmeling fight. This broadcast is brought to you by Buick.

NARRATOR: June 19, 1936. Yankee Stadium is host to the first meeting of two heavyweight fighters: German Max Schmeling and American Joe Louis.

FIGHT ANNOUNCER (archival): There's no time in this swiftly moving drama to broadcast who's who in the Yankee stadium. It's an amazing cross-section of America: rich man, poor man, beggar man, thief, doctor, lawyer, merchant, chief.

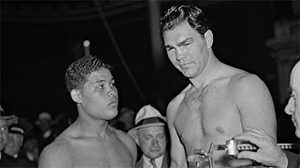

NARRATOR: Though they have come from far and wide to see it, few in the crowd expect much of a fight. In one corner, Joe Louis is the rising star of the heavyweight division, undefeated and by most accounts unbeatable. A combination of speed, power, and aggression, he is considered a near-perfect fighter. The German Max Schmeling, by contrast, is eight years older and on the downward slope of a checkered career. Though possessed of a dangerous right hand, he is considered no match for the American phenom.

FERDIE PACHECO, Fight Doctor: In my neighborhood, we thought that the German was a washed up fighter, that it was almost a crime to bring him in to fight Joe Louis. It's going to be an embarrassment. He's going to go in and knock out this German and that's the end of that.

NARRATOR: Only one man is confident of a Schmeling victory and that is Schmeling himself. For weeks, he has hinted to the press and fellow fighters that he has discovered a flaw in Louis' style.

STEVE ACUNTO, Trainer: I was skipping rope and in walked Max Schmeling. And the reporters were somewhat quizzical, somewhat skeptical, even a little sarcastic. They said well Max what about Joe Louis? He said, I lick Joe Louis, I zee zometing.

REPORTER (archival): Max, have you discovered any particular weakness in the Brown Bomber? "Yes. I did. But I won't tell."

FIGHT ANNOUNCER (archival): And in about five seconds the fight will be on. They're twisting in their corners, there's the bell, and they step out...

NARRATOR: In the early rounds, those in the stadium expecting a quick knockout were instead surprised by a closely contested slugfest, as first Louis then Schmeling gained the upper hand. But as the fight wore on it began to take a decided turn, and with it the lives of these two fighters. Theirs was a rivalry, born that night, that would draw in two nations inching closer to war ... and take the measure of two men who had been fighting all their lives.

RALPH EDWARDS (archival): Joe Louis, tonight, this is your life. Now to get all the answers in your case Joe, find out what makes a champ, let's go back to 1914, May 13th, your birthday... Where were you born? "Lafayette, Alabama." on a farm near Lafayette. One-hundred and twenty acres of poor land rented by your father and mother Monroe and Lilly Barrow. How many children were there Joe? "Eight." Of whom you were the seventh. Your sister Suzie died some years ago and your brother Lonnie passed on last June. But here from Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles are the others: Emerell, Albanias, Deleon, Ulaila, Eunice and your step-brother Pat.

NARRATOR: In 1926, 12 year-old Joe Louis Barrow and his family decided to leave the South. Behind them were 120 acres of Alabama red clay soil and the privations of a sharecropper's life. Ahead, lay Detroit, and the promise of $5 a day at the Ford automobile factory. For thousands of Southern blacks like the Barrows, the job at Ford offered a living and a bit of dignity in their new world.

ADAMS, Louis' Friend: I recall that men would dress up on Sunday and they would wear their Ford badges...

PETTAWAY: On their suits....

ADAMS: Their lapel...their vests...

PETTAWAY: On their suits and go to church.

ADAMS: And go to church with that Ford badge on.

PETTAWAY: Upward mobility. Standard of living. Pulled us out.

NARRATOR: Joe too went to work at Ford while still a teenager pushing 200 pound truck bodies on a conveyor belt. In the summer, he hauled ice in the Negro section of Black Bottom. Soon, his lean physique was layered with muscle.

WALTER SMITH, Louis' Friend: The first time I seen Joe, he worked on a ice wagon... They had to go up sometimes three flights of stairs with a seventy-five pounds or a hundred pounds of ice. And that was a big job going up three flights of stairs with uh, ice on your back.

NARRATOR: Joe never had much use for school -- or anything else that required him to speak. He had battled a stammer since early childhood, and learned the habit of silence. All his life, people would mistake this silence for dullness, and Joe never bothered correcting them.

RALPH EDWARDS (archival): Was there anything about Joe as a boy that showed he would be a great champion in the ring, Deleon? "I hardly think so. He could run faster than most boys. He hit kids bigger than himself. But Joe was mostly quiet and stayed to himself."

ADAMS: He was a little slow until he started boxing, and after he got to be champion, he still was slow.

PETTIWAY: Well, listen Garcia, I didn't know it until later but he went to the Brownstone School.

ADAMS: Brownstone School

PETTIWAY: For slow learners.

ADAMS: Yeah, for slow...

PETTIWAY: Special education.

ADAMS: And Thurston McKinney.

PETTIWAY: Did Thurston go there too?

ADAMS: That's where Thurston went.

NARRATOR: Thurston McKinney was a fast light heavyweight, and one of Joe's running buddies on the streets of Black Bottom. As legend has it, he was the one who introduced Joe to boxing. Joe's mother had given him half a dollar a week for violin lessons, hoping to keep him out of trouble, but Thurston had other ideas for the money.

WALTER SMITH: Thurston McKinney told him, hey, you look like a, a sissy, wanting to play violin, ain't nobody play no violin, he said, why don't you go up to the gym and learn how to box?

FIGHT ANNOUNCER (archival): In the 75-pound division, Slugger Sullivan meets up with KO Molfo in a one rounder, with no holds barred...

NARRATOR: It was only natural that Joe Louis should find the boxing ring. Two bits for a locker was all a kid needed. In the teeming ghettos of America's big cities, boxing became a flag of ethnic pride: every neighborhood had a champion.

JACK NEWFIELD: In the '20s there were great Irish fighters there were great Jewish fighters there were great Italian fighters, and particularly in New York and Chicago there were these rivalries built on ethnic tension, and you could get ten thousand people for a fight between two neighborhood heroes

NARRATOR: Through much of the Twenties, the heavyweight champion of the World was Jack Dempsey, a man held in higher regard by working class Americans than the President or the Pope. Dempsey once drew 100,000 fans to a bout. It wasn't hard to figure: there was big money in the fight game.

DON MAJESKI, Boxing Promoter: As great as Babe Ruth was, who made eighty thousand dollars at the peak of his career in salary, Jack Dempsey in his fight with Gene Tunney in 1926 made seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars. That's more than the entire payroll of the Philadelphia Philly's baseball team, the St. Louis Browns baseball team. It was more than Babe Ruth made cumulatively in his entire career, in one fight.

NARRATOR: Boxing promised Louis not only a way to escape poverty; it was a way to reinvent himself - to leave behind the slow, stammering kid from the cotton fields, and become the fast, fearsome fighter. He quit school for good, dropped "Barrow" from his name, and went simply by "Joe Louis".

FIGHT ANNOUNCER (archival): Madison Square Garden puts on a cauliflower show...

NARRATOR: Louis first made his mark in the 1934 Golden Gloves tournament, where he made it all the way to the finals. There were plenty of other good fighters around: some worked harder, some moved better. But nobody could remember seeing a kid punch like this.

HERB GOLDMAN, Boxing Historian: Punching power is something to a large extent that cannot be taught. It can be strengthened; you can make a fair puncher into a good puncher. A great puncher like Louis they say is born. It's the right coordination, the right build everything coming together in a number of ways. And it is a sure ticket to the big money

NARRATOR: The scent of money is what brought around a small-time racketeer named John Roxborough. Roxborough was king of the illegal numbers lotteries in Detroit. But one glimpse at Joe in the ring and he knew it was time for a different scheme.

ADAMS: Investment.

PETTAWAY: That's right.

STUBBS: Money. Money honey.

ADAMS: That's what it was, money

NARRATOR: Roxborough partnered up with a wealthy and connected numbers man from Chicago named Julian Black.

RALPH EDWARDS (archival): Here he is Joe your good friend and co-manager with John Roxborough Julian Black of Chicago.

NARRATOR: Together, Roxborough and Black could manage Joe's business affairs, but they knew they'd need help teaching him how to box.

RALPH EDWARDS (archival): Tell us now what was the next step Julian? Well Ralph, our first big problem was to get the best trainer available and we were fortunate to get the late Jack Blackburn.

NARRATOR: Jack Blackburn, a convicted murderer with a notorious mean streak, had already trained several white world champions.

BUDD SCHULBERG, Writer: When Roxborough called him in to take young Joe on Blackburn's reaction was that he didn't want to waste his time. Said a black heavyweight. What's the use, I'm just wasting my time because nobody will give a black heavyweight a chance. He was very bitter and totally cynical.

NARRATOR: Blackburn's cynicism sprung in part from his own bitter experience. One of the most skilled lightweights who ever lived, his career had been undermined by boxing's color line. While lesser white fighters had become famous and rich, he had brawled in the back rooms of bars for the price of a few bottles of whiskey. In the end, Blackburn couldn't pass up the guaranteed $35 dollars a week, and then too, he thought he saw something special in Joe.

BUDD SCHULBERG: I think Blackburn really loved nobody white or black or green or brown I think he really loved Joe. He also saw the enormous possibility in him.

NARRATOR: Blackburn would teach Joe the finer points of boxing, but perhaps more importantly, he warned him about what to expect as a black fighter. "What you got to do every single time you get in the ring," he said, "is knock the other fellow down. You gotta let your right hand be your referee." The same year that a young Joe Louis first landed in Detroit, another future heavyweight, 20 year-old Max Schmeling, arrived in Berlin. Liberated from the tyranny of the Kaisers, Berlin in 1926 was a fantastic whorl of cabarets, theaters, and drinking spots.

MARTIN KRAUSE, Journalist: Berlin was the only cosmopolitan city in Germany -- a city of millions. When he came to Berlin a penniless young man, it must have been overwhelming: the variety of possibilities, the distractions.

NARRATOR: The son of a working-class sailor, Schmeling had discovered boxing in small clubs in his hometown of Hamburg. Once in Berlin, his talent caught the eye of Germany's leading boxing writer, Arthur Bulow. Bulow agreed to pay his training fees and become his manager. With Bulow's patronage, Schmeling rose quickly, becoming first German, then European champion. His rise was followed avidly by Berlin's largely-Jewish avant-garde, who had fallen in love with boxing.

GEROGE VON DER LIPPE, Professor, St. Anselm College: It was new, it was different, it smacked of America. It was somewhat rebellious. It was just almost became a cult among the intellectuals, uh, the cabaret society set in Weimar Berlin. It was part of the decadence, it was part of the excitement

NARRATOR: Max took to the strange world of Weimar society as if he had been born to it. Within two years, the raw provincial boy was wearing tux and tails and attending all the best parties...

DAVID BATHRICK, Professor, Cornell University: He knew all of the Berlin avant-garde, they wanted him to teach them how to box. They painted him, they sculpted him. He became a kind of fetish for them.

GEORGE VON DER LIPPE: He goes on a self-improvement campaign. He starts reading books about and by his new circle of friends. He seemed to always be able to adapt. If I had a theme for Max's life it would be that he's a survivor, he adapts to the situation, he adapts to the people he's dealing with.

NARRATOR: By 1928, Max Schmeling had achieved everything he could in European boxing. He and his manager Arthur Bulow set sail for New York and a shot at boxing's biggest prize: the heavyweight championship of the world.

NARRATOR: Since the late 19th Century, the heavyweight championship had been largely the property of America, and within America of the white race. There had only been one black heavyweight champion before and many white Americans vowed that he'd be the last. His name was Jack Johnson.

LEON LITWACK, Historian, University of California: there was a term at the time that was used of the "bad nigger." The bad nigger is the, the threatening nigger, the one who lusts for white women. And this was the baddest of them all

NARRATOR: Johnson cut a broad swath through the consciousness of America with his fists and his mouth. As he brawled his way to the world championship in 1908, Johnson became notorious for taunting and humiliating his white opponents. But he was even more provocative outside the ring, consorting openly with white women.

JACK NEWFIELD: He desegregated more whorehouses than anybody in history. He was a wild man. There's a famous story that he's driving through Georgia and the sheriff stops him and says you're driving eighty miles an hour, you're fined fifty dollars. And Jack Johnson hands the sheriff a hundred dollar bill and says, 'I'm coming back the same way'.

JEFFREY SAMMONS, Historian: Jack Johnson had to be the bravest man in America. I'm amazed at what he did publicly that many would not dare to do privately. In fact even looking at a white woman could be a death sentence at the time

NARRATOR: Fight promoters began to look high and low for "a Great White Hope" who could end Jack Johnson's reign. When none was found, federal prosecutors stepped in with a trumped up morals charge. But it was other black fighters who would pay the steepest price for the bigotry Johnson stirred. For the next decade, while Jack Dempsey ruled the ring, his best competition watched from outside the ropes.

ROXBOROUGH (archival): I'm satisfied that you will be the next heavyweight champion of the world.

LOUIS (archival): I hope so.

ROXBOROUGH (archival): Well, Joe, as your manager, I will do everything possible to get you a chance to fight for the championship.

LOUIS (archival): Thank You.

NARRATOR: John Roxborough refused to be discouraged by boxing's color lines. Two decades after Jack Johnson had been forced from the ring, he believed it was time for another black heavyweight champion, and he thought he had the fighter to do it.

JEFFREY SAMMONS: The person who was going to get the shot at the heavyweight title had to be a special individual. Not only a great boxer, but this person had to be more. This person had to be non-threatening to white society, to white dominance, to white values.

NARRATOR: Roxborough and Black set down a series of rules for their young fighter, which they shared freely with reporters.

JEFFREY SAMMONS: He could not gloat over opponents. He could not be seen in public with white women. He had to be seen as a Bible reading, mother loving, god fearing, individual, and not to be too black.

DAVID MARGOLICK, Writer: the shadow of Jack Johnson was hanging over everything that Roxborough and Black did. They set out deliberately to create somebody who was precisely the opposite of Jack Johnson.

NARRATOR: Joe had already seen what happened to impudent blacks in his own lifetime, so he willingly donned the mask of the "Good Negro".

TRUMAN GIBSON: Nobody knew how deeply Joe really felt, because remember Black and Roxborough had schooled him to suppress his, his emotions. So he, he never really showed them.

NARRATOR: The mask was not just for the outside world, it was also for Joe: a way to shield himself from revealing too much of what was inside. "He says less than any sports figure in history" observed one writer. "And that includes Dummy Taylor, the mute pitcher for the Giants." Only in the ring could Joe really let himself go and he did so with a fury that thrilled -- and terrified. By the middle of 1935, Louis had won his first 23 professional bouts -- an average of one every two weeks --and was beginning to earn glowing notices. But he hadn't fought east of Detroit yet. The road to the big prize, the heavyweight championship, stretched ahead a thousand miles to New York.

SOT (archival): SHIP WHISTLE BLOWS

NARRATOR: Seven years earlier, in 1928, Max Schmeling had arrived in New York with his own roadmap to the heavyweight crown; but New York hardly took notice.

HERB GOLDMAN: In the 1920's, foreign fighters were not treated well in New York City. One could be a national champion of Germany or France, or Italy, or any other country you were still treated like a six round fighter in New York.

NARRATOR: In typical fashion, Schmeling adapted to his new surroundings. He abruptly fired his mentor Aruthur Bulow, and hired in his place a wily New Yorker named Joe Jacobs, known widely as "Yussel the Muscle".

DON MAJESKI: This was the quintessential boxing manager of the twenties and thirties. Cigar-smoking, Fedora-wearing guy. Uh, had the uh, the boutonniere on his lapel would go in and talk a mile a minute...He was the guy who could open doors. He was the guy who get him the publicity. He was the guy who had the contacts. That's the biggest thing in boxing: he had contacts.

REPORTER (archival): Hello everybody. Greetings from the training camp, Greenkill Lodge, Kingston, New York.

NARRATOR: They made an unlikely pair: the square-jawed Teuton and the wiry, wise-cracking Jew.

REPORTER (archival): Max Schmeling is now quartered in the finest training camp ever assembled...

NARRATOR: But the partnership worked.

GERHARD REIMANN, Sports Writer: There was a saying that Joe Jacobs couldn't see the difference between a left hook and a right cross, but he knew how to sell. That's why Yussel Jacobs who wasn't very much liked was the right man.

DEMPSEY, SCHMELING (archival): Well Jack, we certainly do look like brothers. Well we certainly do Max.

NARRATOR: It didn't hurt that Schmeling was a dead-ringer for Jack Dempsey. Soon, Jacobs was placing flattering profiles in the sports pages and getting fights. In 1930, after only two years in America, Schmeling landed a bout with Jack Sharkey for the vacant heavyweight championship. Eighty thousand fans filled the Yankee Stadium in a fight billed as a battle between the continents Sharkey came out swinging, and was out-pointing Schmeling on all the judges cards. But in the fourth round, he made a fatal mistake. Corralled against the ropes, he slugged Schmeling below the belt.

DAVID MARGOLICK: Schmeling clutched himself and fell onto the canvas and started to get up... It was at that point that Joe Jacobs sprung into action and stood up and started shouting don't get up, don't get up, you were fouled, you were fouled ... he starts running around the ring, he starts running to the ref, he starts pleading Schmeling's case, There's this moment of great indecision and tumult in the ring and outside the ring. And finally um, Schmeling was declared the victor.

NARRATOR: Schmeling returned to Germany with a heavyweight title, but little honor.

GEORGE VON DER LIPPE: He's called "the low blow champion." He becomes the punch line of jokes. He becomes an object of disdain for many cabaret routines.

NARRATOR: The Germany Max returned to was a far darker place than the one he had left. The economy was collapsing under an avalanche of worthless marks - unemployment was rising, and with it violence in the streets. Once on the fringes, the Nazi Party was drawing strength from chaos. Suddenly, the implacable glare of the Party's leader could be seen everywhere. In January, 1933, Adolph Hitler assumed sole power over Germany and immediately began a quiet campaign of terror. Many of Schmeling's old friends -- Jews, homosexuals, communists who had found a home in the Weimar cabarets - suddenly found themselves outcast and fled or were banished from the new Germany.

DAVID BATHRICK: May 10th after the takeover, there was a book burning. And a lot of those books were by these artists that had been very close to Max Schmeling. So all of these people were in trouble once the political winds had shifted.

NARRATOR: But Max had already tacked again and set himself with the prevailing winds. In 1932, he had married the Czech-born movie star Anny Ondra. Blond and beautiful, she was the picture of an Aryan princess and a favorite of Hitler's inner circle. Max and Anny became Germany's most glamorous couple, even appearing together in a popular movie. The same year, Schmeling fought a rematch against American Jack Sharkey.

FIGHT ANNOUNCER (archival): The winner and new World Champion...

NARRATOR: This time, he lost his title in a widely condemned split-decision.

DAVID MARGOLICK: He got redemption in the only way that he could. He was seen to be a victim, a victim of a political decision in a way, and so when he came back to Germany all of a sudden he was a hero.

GERHARD REIMANN: The people really seemed to like him. The way he had, the looks you know. There's an old Jewish saying: you have to have a punem as well, you know a punem and Schmeling had that certain look which attracted the people.

NARRATOR: Max' fame brought him freedom to pursue his career in America, great wealth, and access to the highest echelons. At first, Schmeling had no particular fondness for Hitler. In fact he and Anny laughed over the Fuhrer's resemblance to Charlie Chaplin. But Max did admire power and understood its usefulness.

MARTIN KRAUSE: When he wanted to help somebody, he always turned directly to Hitler or his aides. He liked to associate with them. This doesn't necessarily show a love for the Nazis, but rather a love of the powerful, of people who stood in the spotlight. Schmeling wanted to be the center of attention. Schmeling tried to ingratiate himself on two continents: He courted American fight fans, visiting New York often with Joe Jacobs conspicuously by his side. But he was also willing to carry out the bidding of the Nazi regime. As he prepared to return to New York in June, 1933, Hitler summoned him for a meeting.

DAVID BATHRICK: And toward the end Hitler says two things. On the one hand, he said: if you run into problems, feel free to contact me if I can be of any help. Uh, the second thing he says is when you go to the United States, um, you're going to obviously be interviewed by people who are thinking that very bad things are going on in Germany at this moment. And I hope you'll be able to tell them that the situation isn't as bleak as they think it is. And that basically was the contract under which the two of them would operate from that point on. It certainly was a devil's contract.

NARRATOR: Only days after their meeting, Hitler purged German boxing of Jews. He ordered a national boycott of Jewish stores. Many business were ransacked and destroyed, and Jews paraded in the streets. Nevertheless, upon his return to New York, Schmeling upheld his end of the bargain.

VOLKER KLUGE: After arriving in the States, Schmeling held a press conference. Many journalists were waiting to hear about conditions in Germany. Schmeling told them that everything was okay and quiet in his home country. He denied that Jewish people were persecuted. His assignment was to calm down the American people.

NARRATOR: But Schmeling's efforts to please both his government and his American public could at times could tangle him and his manager up in knots. In 1935, he fought a come-back bout against the American Steve Hamas in his hometown of Hamburg.

VOLKER KLUGE: The event very much resembled a Nazi party convention. There were SA bands playing. Speeches were made, there were un-ending "Sieg Heil" and "Heil Hitler"- cheers, ending with Schmeling's victory over the American.

NARRATOR: After Schmeling knocked out Hamas, he and twenty-nine thousand fans spontaneously stood and sang the Nazi anthem with arms raised in the Sieg Heil.

DAVID MARGOLICK: It was a moment of high Wagnerian pageantry. And in the middle of it all, Joe Jacobs climbed into the ring and also gave the Nazi salute. It made the Nazis unhappy because here was this Jew giving the Nazi salute and not only that, he had a cigar in his hand, which they thought was a terrible impertinence.

NARRATOR: Jacobs reception in America was no warmer when a photograph of the salute appeared in newspapers the next day.

Up in the Bronx the good burghers agreed that the little man with the big cigar was no credit to their creed. in the Broadway delicatessens and nighteries where Playboy Jacobs is a familiar figure the waiters were conspiring to SLIP Mickey Finns in his herring.

JACK MILEY, NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

NARRATOR: While Max Schmeling rode out the vicisitudes of an up-and-down career, Joe Louis was heading in one direction only: straight up. By 1935, Louis had raced through the lower ranks of professional boxing. Next stop, the big-time: New York.

JACK NEWFIELD: In the 1930s, New York was the capital of boxing. The Mecca. There were no casinos, there was no Las Vegas, there was no Atlantic City, big fights happened at 50th Street and Eighth Avenue in the old Madison Square Garden.

NARRATOR: New York boxing was controlled by one company: the giant Madison Square Garden Corporation. The Garden promoted the fights and owned the fighters -- and they wanted nothing to do with a black heavyweight.

W.C. HEINZ, Sportswriter: Jimmy Johnston was running boxing in Madison Square Garden and he had a phone call from John Roxborough out in Detroit. And John Roxborough offered him Joe Louis. And Jimmy Johnston didn't know John Roxborough was a black man. And Jimmy Johnston said: 'We don't need the nigger'. So that's how Madison Square Garden lost Joe Louis.

NARRATOR: There was one fight promoter willing to take a chance on Joe: Mike Jacobs, otherwise known as 'Uncle Mike'. Jacobs -- no relation to Schmeling's manager - owned a thick New York brogue and a set of poorly-molded false teeth: through which he'd mutter his signature line: 'What's in it for Uncle Mike?'

HANK KAPLAN, Boxing Historian: He was a street kid and sold newspapers and first... he would go to the box office and buy tickets for the scalpers. Until he began to realize that uh, heck he could do this for himself.

NARRATOR: Uncle Mike could turn anything to his advantage, even the Depression, which finally gave him his chance to go after the Madison Square Garden's monopoly on boxing. For years, the Garden had donated generously to the Milk Fund for Babies, the favorite charity of Mrs. William Randolph Hearst, wife of the newspaper tycoon. In gratitude, Hearst's stable of big-time sportswriters spilled gallons of ink promoting the Garden's fights. But with boxing in the doldrums thanks to the Depression, the Garden had cut back on Mrs. Hearst's charity. Uncle Mike stepped in.

MIKE SILVER: He made a deal with them to promote his own shows uh, with a bigger portion going towards the Milk Fund charity. And in doing so, he became very chummy with some of the major newspaper reporters for, and a columnists for the Hearst newspapers. This was a, a master stroke.

NARRATOR: Jacobs convinced three of Hearst's biggest sportswriters to join him in a new venture: The Twentieth Century Sporting Club. With the backing of the Hearst papers, Twentieth Century began to compete with the Garden for the biggest boxing promotions, drawing thousands to the cavernous New York Hippodrome.

JEFFREY SAMMONS: Mike Jacobs has the venues, he has the press behind him, but he needs a big draw. And he sees something special in Joe Louis

NARRATOR: What Mike Jacobs saw was not Louis' skin color, but his already strong hold on black Americans, whose money was as green as anyone else's.

DAVID MARGOLICK: There were these stories working their way back east about this mythical boxer who was going to be the Moses of boxing. So you have this incredible scene where Joe Louis comes to New York for the first time in May of 1935 and the bellhops carry him off the train. They all knew who he was and they were waiting for him to get there.

NARRATOR: With an evangelical following of black fight fans, Mike Jacobs rushed to set up a coming-out party for his heralded young phenom.

MIKE SILVER: What they needed was a name opponent and a sacrificial lamb to show Louis at his best.

NARRATOR: Jacobs settled on an ex-heavyweight champion, the Italian giant Primo Carnera, otherwise known as the "Ambling Alp".

HERB GOLDMAN: Carnera was between six foot five and six foot six. He weighed generally between two hundred and sixty and two hundred and eighty pounds. And there uh, were people, sportswriters included who claimed there should be a special dreadnaught class for men like Carnera.

NARRATOR: In fact, Carnera was hardly a fighter at all. For years, he'd been managed by New York gangsters, and had won a series of fixed fights, including it was rumored, the World Championship in 1933. Over time, Carnera had learned some rudimentary skills in the ring. But what was most important to Mike Jacobs was that the paying public loved him. The Louis Carnera fight was the most anticipated to hit New York in a decad. Mike Jacobs' publicity agents had cleverly linked the fight to a brewing international crisis: Italy, symbolized by the giant Carnera, was preparing to invade the Kingdom of Ethiopia, embodied by the relatively diminutive Louis.

FIGHT ANNOUNCER (archival): Regardless of race, creed, or color may the better man emerge victorious.

NARRATOR: In the end, the Man Mountain turned out to be more like a molehill. Louis knocked him out in the 6th round. "Primo came down slowly," one reporter wrote, "like a great chimney that had been dynamited."

NARRATOR: After the fight, more than 20,000 people showed up at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem where Louis had promised to appear - win, lose or draw. When the fighter finally showed, he wore his usual blank expression, "as if the crowd were looking at someone else", one writer remarked. "It was all too big and too much for just a kid," Louis would later say. But in fact it was only just beginning. Overnight, Louis had become the biggest draw in the fight game. Over the next year, Jacobs easily set up opponents for Joe and Joe just as easily knocked them down.

HERB GOLDMAN: Louis was going through the heavyweight division like Sherman through Georgia: Kingfish Levinsky, one round. Max Baer, four rounds. Primo Carnera, six rounds. Stanley Poreda, one round. Lee Ramage, three rounds. Nobody can do anything against this young man. He has the big punch, he has the power, he has the style, he is capturing the popular imagination.

NARRATOR: With each victory, Joe's stature in black America rose higher.

VERNON JARRETT: We invested so much in Joe Louis when he started winning, we needed some victories the fact that Joe Louis was winning without any dispute over white America. He was our nonviolent, violent way of expressing ourselves.

WALTER SMITH: We had never had guys to look up to when he first started. We didn't have nobody. He comes on and we had somebody to look up to.

NARRATOR: Ravaged by the Depression and virulent racism, many blacks invested Joe with the strength they lacked.

In North Carolina, an inmate bound for the electric chair was said to have cried: "Save me Joe Louis, Save me."

JEFFREY SAMMONS: Joe Louis's victories over white opponents were palpable and tangible. And blacks saw in them something that, that fed them

NARRATOR: Joe tried to live up to peoples' expectations, but the adulation of the outside world was making it harder to play the "Good Negro".

He was making serious money now, money he could never have dreamed of back in Detroit.

And there were women too: they couldn't keep their hands off him.

ALVERTA BARKSDALE, Dancer: He had a beautiful body. And he, there was no fat on him, he.... And then he was big and muscular and a beautiful color. Kind of coffee colored with cream, double cream. He was just a beautiful man

NARRATOR: Louis had become so big, so fast that he no longer had time for his managers' sermons.

ALVERTA BARKSDALE: I happened to be in different cities when he would come through and uh, there was always a woman in that city although I don't know names. But I would see girls. Sometimes it would be chorus girls or a singer from a show -- he scored.

NARRATOR: Trying to keep the mask from slipping, Joe's handlers encouraged him to marry a beautiful young secretary named Marva Trotter. The couple walked the streets of Harlem like movie stars. But nuptials did little to slow Joe down.

STUBBS: I heard that Roxborough picked that girl for him.

ADAMS: He did. They did. He picked her. He was getting into things. And they decided he that should marry somebody. She was attractive, she was intelligent and he said well I'll just go along with the program. When they was in town. We'd slip off to Toledo at night, slip away from Marva, and I don't know it was just one of those things. It look like it was just a business deal. You got the marriage to keep you out of trouble.

NARRATOR: Unlike Jack Johnson before him, Joe never flaunted his personal life, and sportswriters kept his secrets. But that didn't mean they treated him well. In the end, the mask could only offer Joe so much protection from white racism.

JACK NEWFIELD: America was a different country in 1934 and 1936 and if you go back and read the sports writing of the '30s, there are despicable repugnant stereotypes of Louis as dumb, as lazy, on one hand, or as an animal of the jungle on the other hand.

I felt myself strongly ridden by the impression that here was a truly savage person, a man on whom civilization rested no more securely than a shawl thrown over one's shoulders. I had the feeling that I was in the room with a wild animal.

-- PAUL GALLICO, NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

NARRATOR: Louis was picking up a growing number of white fans - laid low by the Depression themselves - they responded to his rags-to-riches story. But there were still millions who wished to see Joe stopped in his tracks. "Good Negro" or not, he was still a black man physically dominating his white opponents. And so many hankered for the return of a "Great White Hope". But few imagined that the savior might come in the form of an aging fighter from across the Atlantic.

NARRATOR: By 1936, Max Schemling's up-and-down career was on an upswing. He'd won four fights in a row in Europe, and scrapped his way back into contention in the heavyweight division. Despite his age, he had become the next logical opponent for Joe Louis. The fight would be crucial: the winner to get a shot at the world champion Jimmy Braddock, a former longshoreman with brittle hands who had come to be known as "The Cinderella Man".

DAVID MARGOLICK: When Louis fought Schmeling the idea was that either one of them could beat Braddock and therefore what mattered was who would have the privilege of fighting Braddock first. This was really the fight for the world championship.

NARRATOR: No one gave Max much of a chance. The boxing press scoffed, calling him "Moxie" Schmeling for daring even to take the fight. But Schmeling would not yield to doubt. He schooled in Nazi propaganda, he believed he had one decisive advantage over his opponent...

GERHARD REIMANN: I think that he thought that he could outthink him. That his brain was better than that of Joe.

NARRATOR: Schmeling began to study Louis' fights, looking for something, anything he could use to his advantage.

BUDD SCHULBERG: I think that with a Germanic thoroughness that Schmeling had he looked at every - every available foot of film on, on Louis. He not only ran it forward - he would stop it - he would actually run it backward - he would put it in slow motion.

NARRATOR: After weeks of study, Schmeling believed the film had yielded something -- a small defect in Louis' overwhelming attack.

HANK KAPLAN: When Joe Louis jabbed and he was a great, he had the great, greatest jab in the history of boxing up to that time, he would jab but his jab would come down to his waist rather than up to his face

GERHARD REIMANN: Uh, and that was the split second where Schmeling could land his uh, right hand. He, he believed in that.

REPORTER (archival): Have you discovered any particular weakness in the Brown Bomber? "Yes, I did. But I won't tell."

NARRATOR: Schmeling left Germany for New York with little fanfare. Unlike Max himself, the Nazis had no confidence that he could win. On the orders of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels', Nazi newspapers had buried the story of the fight.

GERHARD REIMANN: Hitler was annoyed that he was going to fight a Negro. Schmeling with a Jewish manager and fighting a Negro, a nigger. No, no, and, and I don't think they expected him to have a chance.

NARRATOR: At his Lakewood camp, Louis seemed overconfident; and the only person who could have whipped him into shape was in no shape himself.

TRUMAN GIBSON: I think at that point, Jack Blackburn's problems had affected him. Jack was drinking: his camp was confused. And uh, his mind was diverted.

NARRATOR: But Schmeling was focused, more focused than ever before. He was not only working on his body, but on his mind. He knew that to land his right hand, he would have to be in close, and that meant overcoming his fear.

GEORGE VON DER LIPPE: Max thought that part of his strategy would have to be showing no fear. During the weigh-in he walks up to Joe Louis, shakes his hand, says, hello Joe, how do you do... he comes away and shouts over his shoulder, good luck this evening, Joe. Joe Louis and the press are, are perplexed by this show of courteous bravado.

FIGHT ANNOUNCER (archival): And in about 5 seconds to go before the fight, the fighters are twisting in their cornerns and here's the bell...

NARRATOR: Both fighters came out cautiously, feeling each other out.

HANK KAPLAN: Schmeling would probe with his left jab. He didn't care if he, if he touched the opponent or not, but it was out there, he would probe with it and he'd move and he'd be looking for openings.

STEVE ACUNTO: every time Louis jabbed, he'd return his left hand low at his side, rather than up here where it's supposed to be, where he could block a counter right hand.

NARRATOR: At just over 2 minutes into the fourth round, Louis jabbed and Schmeling pounced.

HANK KAPLAN: He saw Joe Louis' hand drop. When that hand dropped, he came over with a right cross. Boxing is a very unique sport. You can have all the great assets like Joe Louis had, speed, great boxing ability, great footwork, great left jab, tremendous power in your punches, but if you're hit on the chin, all those assets go right down the drain.

NARRATOR: At that moment, Schmeling would later say, Louis changed from an indestructible force to "a hurt and bewildered boy".

HANK KAPLAN: He was out of it,' he wasn't himself for the rest of the fight. He was fighting on heart and instinct alone. After that it wasn't Joe Louis anymore, he was just a punching bag.

NARRATOR For round after round, Schmeling continued to batter Louis with his right hand. Mid-way through, Joe's mother Lilly had to be led from the stadium screaming: "My God, don't let him kill my child."

STEVE ACUNTO: There was a pop, pop, every time one of those right hands landed. It sounded like a bag full of water coming down from the second floor of a building: "POP, POP', POP"

PACHECO: You just can't get hit by right hands by a heavyweight repeatedly. I don't care who you are. You get hit enough right hands, you're going, you know? And Schmeling could punch. And Schmeling was a good boxer. And Joe was slow. And over-confident. And believed nobody could beat him, and he found out different.

NARRATOR: Finally, in the twelfth round, the punishment became too much.

CLEM: (archival): And Schmeling came back with a terrific right to the jaw... and then at close quarters, Schmeling shot a hard right to Louis' jaw that landed flush. And Donovan broke them. Schmeling got over two more hard rights to Louis' jaw and made Louis get down, and Schmeling straightened up Louis with hard rights and lefts to the jaw...He has puffed up Louis' cheek, and Louis' is down! Louis is down! Hanging to the ropes and hanging badly! He's a very tired fighter, he is blinking his eyes, shaking his head and the count is ten. The fight is over! The fight is over! LOUIS IS completely OUT!

JIM CLARK: You talk about after the fight now, there were throngs of people coming down the middle of the street, Everybody was just as quiet and all you could hear was oh, Louis was doped. I think he was doped.

WALTER SMITH: Everybody was sick. Usually after Joe Louis got through fighting, everybody would be out in the streets, driving, honking their horns and doing this. And not only in Detroit, Philadelphia, New York and Chicago, everywhere. Not that night, no.. it was a sad night... it was like a funeral it was... Nobody came out, no horns honking, no nothing.

ALVERTA BARKSDALE: I was sitting in my husband's lap and he was losing the fight and I was crying because he was losing the fight. If I think about it hard enough I'll cry again.

I just can't help thinking of the bitter disappointment, the shattered hopes, the tears and the heartaches that fell upon an entire race just before 11 o'clock last night. An idol fell and the crashing was so complete, so dreadful and so totally unexpected that it broke the hearts of the Negroes of the world.

THE NEW YORK POST

NARRATOR: As fast as Louis had been built up he was now torn down.

JEFFREY SAMMONS: The press denunciations were vehement, brutal, that he was a fabrication that this was all a kind of buildup of a nobody.

This brown god had crumbled before our eyes and his substance was dross and alloy and clay. Louis, the flawless fighter, was a myth, a delusion ... a legend that never happened.

DAVIS WALSH, HEARST NEWSPAPERS

NARRATOR: Louis himself immediately left New York for the solace of his home-town. Even there, he hid out, too ashamed to show his face.

ADAMS: Joe come on the playground about a week after his head was swolled up, and dark glasses. He didn't get out of the car. He just stayed in the car with his head swolled up

JOE LOUIS BARROW JR., Son: When he finally did go in the streets, kids being who they were, uh, would, would run up to him and say, 'Max Schmeling, Max Schmeling'. And I think it got to him because, was he still their hero? Was he still the Great Black Hope?

NARRATOR: Max Schmeling could finally return to Germany to a hero's welcome. Upon landing in Frankfurt, he was greeted by thousands of his countrymen lining the roadway for miles. Always attentive to the public mood, the Nazis turned their cool handshake into a warm embrace. Josef Goebbels, who had tried to bury the fight in the German press, now ordered lavish coverage of Schmeling's victory, including a photograph of himself listening to the fight with Max' wife Anny.

Stayed up all night. At 3 am the fight begins. In round 12 Schmeling knocks out the negro. Wonderful... The white man defeats the black man and the white man was a German!

JOSEPH GOEBBELS

NARRATOR: Within days of his return, Max was invited to dine with Hitler.

HANS-JOACHIM TEICHLER: Hitler sensed the great enthusiasm the masses had for Schmeling. Most of all he was electrified when he watched the fight.. He immediately ordered the film to be screened in theaters throughout Germany prior to each feature, it was to be called Schmeling's victory a German victory, the title Goebels invented.

GERMAN ANNOUNCER (archival): Joe Louis is standing in the ring on weak legs, still defending himself but he doesn't have a lot of strength anymore. The feared 'brown bomber' has become a poor, little, beaten negro boy.

FRANZ RAMS: You know it really brought it all back again. We were ecstatic again and very enthusiastic. I remember that there was wild applause.

NARRATOR: The public acclaim was intoxicating. This is what Schmeling had always wanted: the adulation of a grateful nation. But the cheers also made it easier for Max to turn away from what was happening in his country. For a while, perhaps, it had been possible to focus on progress: new jobs, and new optimism. But by 1935, no one could miss the giant rallies exulting the master race; new laws evicting Jews from the professions, and civil service; and the arrests, beatings, and executions of political enemies, including many of Max' old circle.

MARGOLICK: Schmeling writes about how he would go to his favorite clubs and every week there'd be somebody new who was gone. But he just looked the other way. He just didn't want to, he just didn't think about the larger questions.

NARRATOR: Occasionally, Schmeling tried to put in a word for his Jewish acquaintances. If he could do that, he reasoned, what was wrong with meeting with Hitler? How could he, a mere sportsman, stand in the way of the Nazi juggernaut?

GERD OTTO: There were many German personalities, who secretly did not agree with the regime. But they still would have tea with the Nazi big-wigs. Why? Because they thought that staying alive was more important. Everybody who opposed the regime had to fear that the Gestapo would come and take them away.

NARRATOR: But Schmeling was not like other Germans.

VOLKER KLUGE: Schmeling was rich, he was famous. He spoke English well. He had close friends in America and other countries. He would have been welcome everywhere as the famous man that he was.

NARRATOR: Other prominent Germans had chosen to emigrate rather than live under the Nazis. Actress Marlene Dietrich, author Thomas Mann, film director Fritz Lang among others helped to open the eyes of the world to what was going on inside the Nazi state. But Schmeling remained silent, preferring the hero's life in Germany to an uncertain fate outside it.

VOLKER KLUGE: He was loyal to his government. But his loyalty had a price. He had to burden his conscience with the dark sides of the regime, which were so obvious: the dictatorship, the camps, the persecutions, the discrimination. He accepted all this for the sake of his own wealth and fame.

NARRATOR: In later years, Schmeling would make much of the fact that he never became a member of the Nazi Party. But, in fact, the Nazis had no interest in recruiting him. At one point, a friend of Schmeling's wrote to the head of the SS Heinrich Himmler, asking if Schmeling should become a Party Member

VOLKER KLUGE: The responding letter by Himmler's adjutant states that the Fuehrer had decided Schmeling would be more useful to the German people if he neither belonged to the Nazi Party, the SS, the SA nor any other organization. It was very pragmatic.

DAVID BATHRICK: Schmeling was most useful as somebody who was apolitical. He was very useful as being apolitical because he then would be believable. And if he were to come to the United States at the start to give the party message um, that would be the end of the use of Max Schmeling for Adolph Hitler

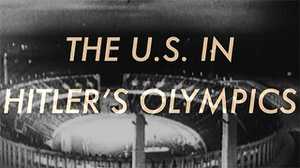

NARRATOR: In the summer of 1936, Hitler came to collect on his bargain with Schmeling. The Olympic Games were about to open in Berlin, and Hitler had big plans for them. If all went well, they would become the proving ground for his notions of Aryan superiority and German national resurgence. But the US Olympic Committee was threatening to spoil the party by boycotting the Games. Hitler looked to Germany's best-known international athlete for help.

DAVID BATHRICK: They asked that Schmeling contact the committee to urge them to understand that there would be no difficulties politically for Jews or for blacks uh, if, if they participated in the Games.

NARRATOR: Quietly, Schmeling met with members of the U.S. Olympic Committee at the Commodore Hotel in New York. Committee members produced clippings of dark tidings in Germany. Schmeling assured them that the reports were false; that Hitler could be trusted. Days later, by a narrow vote, the USOC agreed that America would attend the games. By the summer of 1936, Schmeling could no longer pretend to be living in two worlds. Through small expediencies, he had become a servant of the Nazi government.

TEICHLER: It needs to be stressed that a relationship like this is a process. In the beginning as the naive athlete you feel flattered, then you are used. But this kind of thing doesn't happen in a week. It happens gradually over a period of several years. Both sides form a mutual dependence.

NARRATOR: In the end, Hitler's Olympic dream was marred by a sprinter and long-jumper from the United States named Jesse Owens.

OWENS (archival): I am very glad to come out on top. Thank you very kindly

NARRATOR: Owens' four gold medals were a salve to black America in the wake of Joe Louis' defeat two months earlier: here was the vindication so many had waited for.

NARRATOR: Joe was happy for his friend, but Owens success only deepened the shame of his own defeat. As if to erase the memory, he fought furiously, winning a string of seven bouts in eight months. All he wanted was a rematch with the German. But Schmeling had other plans. As a reward for having beaten Louis, he inked a contract to fight the aging and vulnerable world champion Jimmy Braddock, the Cinderella Man. The prospect of a Schmeling-Braddock bout panicked the Louis camp.

HERB GOLDMAN: Mike Jacobs thought that if Schmeling won the championship, he would go back to Germany and Hitler would actually take over the title and use it for his own purposes

NARRATOR: Mike Jacobs went to work, spreading rumors that the fight would be widely boycotted by Jewish fans -- Braddock wouldn't earn a dime. But if Braddock agreed to fight Louis instead, Jacobs promised he'd never have to work again.

DON MAJESKI: He started offering more money, more money, more money. Finally he came up with a deal. He said, I'll give you not only the biggest guarantee, but you will have ten percent of the profits of Joe Louis's fights for the next ten years.

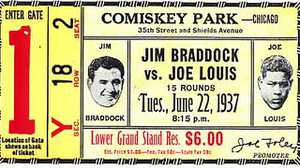

NARRATOR: This was an offer Braddock couldn't afford to pass up. He dropped his plans to fight Schmeling and signed on to face Louis in June, 1937 in Chicago. For the first time in more than two decades a black man would fight for the heavyweight title. More than 60,000 fans, converged on Chicago's Comiskey Park to watch it.

FIGHT ANOUNCER (archival): Here they come. Joe jumping out as usual Jim Braddock steps out fast and lets go with a hard right hand.

NARRATOR: In the first round, Braddock knocked Louis down. For an instant, it looked like a repeat of the Schmeling fight.

FIGHT ANOUNCER (archival): Louis is down from a hard crack to the jaw. Up at two...

NARRATOR: But Louis quickly recovered and in the eight round knocked Braddock senseless.

FIGHT ANOUNCER (archival): Now Braddock is in the center of the ring and Braddock is down... one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten.

NARRATOR: The Cinderella Man had to be carried to his dressing room.

FIGHT ANOUNCER (archival): the winner and new champion of the world: Joe Louis

NARRATOR: Louis had scaled the summit of the boxing world, becoming the first black man since Jack Johnson to attain the heavyweight championship. But to Joe, the championship tasted sour.

BUDD SCHULBERG: Even in a moment of triumph - knocking out Jim Braddock - when people were congratulating Joe: 'You're champ, Joe', Joe said 'no I'm not the champ - I'm not the champ yet. I won't be. I won't be the champ until I lick Schmeling'.

NARRATOR: Max Schmeling was furious over the way the world championship had been snatched from him. He complained bitterly to the New York Athletic Commission, to no avail.

SCHMELING (archival): I zink i got de runaround, I traveled 25,000 miles to face Jimmy for the title. I spent more than 30,000 dollars.

NARRATOR: Now, Schmeling was as hungry for the rematch as Louis. Terms for the fight were quickly agreed upon and the date was set for June, 1938 in Yankee Stadium. From the start, the match was seen as much more than boxing, much more than sports. It was going to pit whole nations, whole ideologies, against each other.

JACK NEWFIELD: This was 1938, Hitler's intentions were clear by then, Hitler's hatred of Jews was clear, Hitler's militarism and expansionism were clear and Schmeling is probably unfairly seen as an extension of Hitler. He's seen as a Nazi.

NARRATOR: Just three months before the fight, Hitler's army (had (could live with this) rolled into Austria without firing a shot. The so-called Anschluss helped to cement Americans' hatred of everything German. When Schmeling arrived in New York by steamer in May, he was met at the dock by hundreds of protesters, and mocking chants of "Heil Hitler". Many Americans channeled their antipathy for Max into affection for Joe.

NARRATOR: Confronted with a choice between a white Nazi and a black American, all but the most hardened racists backed Louis. Even President Roosevelt enlisted Louis in the propaganda against Nazism. Squeezing Joe's arm he said: 'these are the muscles we need to defeat the Germans.' But Joe had little use for the hypocrisy of geopolitics.

NEWFIELD: I think Joe Louis understood that while he was being held up as the symbol of democracy, black people couldn't vote, black people did not have equal rights, the army was segregated.

NARRATOR: For Joe, the motivation was simpler. Quoted in one New York newspaper, Louis said: "I am out for revenge. All I ask of Schmeling is that he stand up and fight without quitting."

LOUIS (archival): People think that I'm going into the fight gun-shy. Why should I be gun-shy when he's two years older and I'm two years smarter in boxing.

NARRATOR: By the day of the fight, bookies had set the line at 2-1 in Louis' favor, but doubts lingered. Could Joe handle the pressure, had he found a defense for Schmeling's right hand? Most expected a long, punishing fight. The evening of June 22nd was hot and sticky. More than 90,000 fans, white and black, streamed in to Yankee stadium, one of the largest crowds ever to pass through the turnstiles.

HERB GOLDMAN: It is a sea of humanity. It is something out of a tremendous political event. There is a rush, there's an excitement which it is almost impossible to describe today.

FIGHT ANOUNCER (archival): The huge crowd, the shifting ever-changing scene. Winking pinpoints of light from 50,000 cigars and cigarettes for all the world likes fireflies in the blue-black night, reaching back, back, back, back till the very last rows are lost in black obscurity. The crowd makes you catch your breath.

ED SULLIVAN (archival): So now, it's June 22nd 1938 ...

NARRATOR: In a nation of 130 million, some 70 million would tune in to the fight on the radio that night, the biggest audience ever for a single program.

DAVID MARGOLICK: The country was immobilized when this fight was on. Dances were interrupted to broadcast the fight. Wrestling matches, movies in movie theatres, the movie was stopped in the middle and, and the fight was broadcast over the loudspeaker.

VERNON JARRETT: I remember walking down the street and people were sitting on their front porches and they had their little radios ready it was real quiet, as though there was just something out here saying, we are about to experience an indescribable event in our lives ...

FERDIE PACHECO: Everybody stopped, they went to whoever had a radio, and you listened. There wasn't anybody, there wasn't any street traffic, I think even the street cars stopped. Everybody stopped and listened to the fight. It was like that moment

NARRATOR: It was 3 am in Germany when Nazi broadcaster Arno Helmis finally took the microphone.

HERBERT HOFFMAN, former German soldier: They woke us up at 2.30 in the morning. We came into the room with a big speaker. We were all the sports fans, the others had stayed in bed. After a while the radio started, and you could hear: " This is Yankee Stadium, New York." Then there was the static, huahue, because the transmission came over the telephone. And then: "The Yankee Stadium is sold out with 70, 000 people. The noise is unmistakable." Then the static again ...

NARRATOR: In Austria, the young Jewish boy Fritz Mandelbaum stayed up late to listen with his father.

FRED MORTON: The fight was ballyhooed in Germany as the fight of the century...: there was the Negro, an inferior race, and the man, Joe Louis, who represented the Negro -- all brawn and animal brutality vs. German noble strength...it is amazing to me in retrospect how much the Nazis really gambled on a victory. The gamble was if you hype it that much, what if you lose?

NARRATOR: Schmeling made his way to the ring under a bombardment of banana peels, cigarette packs, and spit.

LESTER RODNEY: He was pallid. There was something about him, you could smell it you know. And you know it's scary, you, you can get killed here as they say. The roar that began. Just an unimaginable, constant roar. You, you couldn't hear the subway coming out, uh, nothing. The roar up into that Bronx night. if you had any imagination you, you felt the whole country watching.

FIGHT ANNOUNCER (archival): Joe Louis in his corner prancing and rubbing his feat on the rosin and Max Schmeling standing calmly getting a last word from Doc Casey and they're ready, with the bell just about to ring (ding). And there we are. And Louis is in the center of the ring with Max Schmeling circling around him. And Joe Louis lets go with two straight lefts to the chin. As the men clinch. Joe Louis tries to get over two hard lefts and Max ties him up on the breakaway clean. On the far side of the ring now, Max with his back to the ropes and Louis hooks a left to Max' head quickly and shoots over a hard right to Max' head. Louis, a left to Max' jaw, a right to his head, Max shoots a hard right to Louis, and Louis with the old one-two, the first the left and then the right.

FERDIE PACHECO: Almost in the first thirty seconds you could see the way it was going to go. You see his desire just boring in on the guy -- it's spider and the fly ain't got a chance

NARRATOR: He's landed more blows in this one round, than he landed in five rounds of the other fight.

HERB GOLDMAN: He pressed, he drove Schmeling back, he rained punches. Schmeling tried to defend, he tried to counter, he tried to get out of the way.

NARRATOR: Back against the ropes but not too close to the ropes... And Louis misses... Again a right to the body and to the head... He's held to his feet. At just over a minute into the first round, Louis struck Schmeling with a ferocious blow to his side.

LESTER RODNEY: And Schmeling emitted a, a scream. I think everybody went you know sort of like this. Uh, they had never heard a fighter scream in a high pitched voice in agony.

TRUMAN GIBSON: Screams like a woman screams. The scream just went all through the stadium.

FIGHT ANNOUNCER (archival): And again! A left hook! A right to the head! A left to the head! A right -- Schmeling is going down! But he held to his feet, held to the ropes, looks to his corner in helplessness.... and Schmeling is down! Schmeling is down! The count is four and Schmeling is up. And Louis right and left to the head, a left to the jaw, a right to the head, and Donovan is watching carefully. Louis measures him. A right to the body! A left hook to the jaw. And Schmeling is down!

NARRATOR: In a meaningless gesture, Schmeling's corner threw in the towel. Arthur Donovan threw it back, where it hung on the ropes as "limp as the German himself", one writer put it. The count is five, six, seven, eight, the men are in the ring. The fight is over. Max Schmeling is beaten in one round! in less than one round! It was "two minutes and four seconds of murder", one writer marveled, the second shortest heavyweight title fight in history.

FIGHT ANNOUNCER (archival): The winner and still champion: Joe Louis

LESTER RODNEY: People are hugging each other and black and white embracing. Women and men, and strangers. And the scenes were wild jubilation and tears, people crying.

STEVE ACUNTO: It was tremendous. It was almost as though we had defeated the Nazis there and then.

NARRATOR: In Germany, millions had listened to the fight in growing disbelief.

HOFFMAN: Eight, nine, ten. The fight is over, the fight is over. Schmeling is KO'd, Schmeling is on the ground, he can't get up ... and we looked at each other. This cannot be true! This cannot be! The first round had only been half over.

FRED MORTON: To suddenly hear on the air that uh, the announcer very confident saying, "Maxi tu tas und Maxi tu tas, Maxi!'' It was a sense of jubilation that we had, my father and I, and for the first time there was an inkling that Hitler might somehow be stopped.

NARRATOR: In Harlem, news of the victory sent 100,000 people into the streets: "This is their night," the Police Commissioner said, and closed off 30 blocks for the celebration.

LESTER RODNEY: I took the subway down to Harlem. Place was going wild. Little kids you know they're dancing and old, elderly people hobbling on canes you know they, they were looking, oh boy, good, good you know. It, it's the most wonderful thing that ever happened.

NARRATOR: Every saloon in Harlem was packed to the rafters. People who'd never had a sip of beer in their lives, were closing down the town.

CLARK: Everyone was so elated by Louis winning and everything. I got just as high, everything was spinning around, thought I was in a fight. I went back to the Bathroom man, I'm walking on back there, and walked right dead into the lady's room.

There was never a Harlem like the Harlem of last night. Take a dozen Chirstmases, a score of New Year's eves, a bushel of July 4th's and maybe - yes maybe - you get a faint glimpse of the idea.

THE NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

NARRATOR: The celebration wasn't confined to black America alone. For the first time, blacks and whites, even in the deep South, had rooted with all their hearts for the same guy.

VERNON JARRETT: Right after Joe Louis' victory, we got to work ahead of time. And I will say this for this fellow where I worked, he says, well it looks like your man won, I said he sure did didn't he. He says: maybe that'll teach Hitler a lesson.

NARRATOR: Joe had shattered the mask of the "Good Negro" once and for all. All Americans loved him -- not because he was docile and unassuming -- but for the opposite reason: when they were at their weakest, he had reminded them of their strength.

FERDIE PACHECO. I think the word is appreciation. They appreciated him, appreciated what he had done for them. Not only had he saved the honor of the country, but he gave them a tremendous moment of relief from this drudgery of pain that we were in, in the depression. Man it was tough. That night, everybody forgot the depression. Everybody. My mother even gave me a nickel to go get an ice cream cone. That was unheard of, a nickel to celebrate to go get an ice cream cone.

NARRATOR: After the fight, Schemling had been helped to his dressing room.

REPORTER (archival): Max will you say a word to the NBC audience, Max. "Well, ladies and gentlemen, I'm very sorry but I won't make any excuse. I got such a terrible hit. The first hit I get to the left kidneys. I was paralyzed. I couldn't even move." Well max I'm sorry. That's all I can say.

NARRATOR: When Schmeling finally recovered enough to return to his native soil, there was no berth of honor on the Hindenburg, no Luftwaffe escorts, or personal meetings with Hitler.

REIMANN: They dropped him like a hot potato. He wasn't uh, not even consoled or poor Max and so, no, no. He wa...he, he...they had lost every interest in him.

NARRATOR: Schmeling's career was all but over. He fought a few more times but never again in America. Freed from his entanglements with the Nazi government, Schmeling felt able to take risks he'd never been willing to take before. In November, during the national pogrom called Kristallnacht, he sheltered two small Jewish boys, the sons of an old friend, hiding them in his hotel room while gangs roamed outside.

HENRI LEWIN: That man, known all over the world did this for us is an unbelievable thing. This man has done for us what god didn't do. You know how can you explain it better?

NARRATOR:During the war, Schmeling was conscripted into the German army. After it was over he was cleared by British authorities of any complicity in Nazi crimes. Schmeling rebuilt his life one more time - the Nazi idol earned a fortune as a bottler for the Coca Cola company in Germany.

DAVID BATHRICK: He adapted in the Weimar period, he adapted in the Third Reich, and he adapted in 1945 and on. I mean he, he rose again from the ashes.

NARRATOR: Joe Louis went on to become the greatest heavyweight champion in history, defending his title 24 more times over the course of 12 years. His opponents were so overmatched they earned the title "Bum of the Month Club."

REPORTER (archival): Joe Louis answers uncle Sam's call to arms... 'what's your name Joe?' 'my name is Joe Louis Barrow.'

NARRATOR: Joe served his country honorably during World War II. His country didn't return the favor: relegating him to a segregated unit and hounding him for years after for back taxes on money he had donated to the Army and Navy Relief Fund. To pay his debt, he fought on too long, his career finally ended for good in 1951 by a young Rocky Marciano, who wept in his dressing room after the fight. As the years went on, Louis' stature in black America also suffered. New, more assertive black leaders were ashamed of what they regarded as Joe's accommodationism and were eager to dismiss him.

VERNON JARRETT: I wish he'd been a vocal leader. But he did enough for me, by stimulating hope and causing me as a boy to fantasize victories. And that despite everything, nobody is going to stop you from winning if you really set your mind to it. That was enough, I didn't need anything else from Joe Louis. ....

JACK NEWFIELD: When Joe Louis knocked out Max Schmeling he opened a door of history for every great black athlete in the coming generations who could be themselves, who did not have to mask their feelings, who did not have to hide their emotions, did not have to say yes sir and no sir to reporters.

NARRATOR: Halfway through the broadcast of "This is Your Life" in 1960, there was a surprise guest.

RALPH EDWARDS (archival): And the only one you lost? "I won that one on June 19th, 1936 at Yankee stadium in New York. Yes, he's here Joe himself a former world heavyweight champion himself from Hamburg, Germany, the Black Uhlan of the Rhine, Max Schmeling

NARRATOR: It had been more than twenty years since the two fighters had seen each other in the chaos of Yankee Stadium, but it would mark another stage in their relationship. They would meet a dozen more times, always with a great show of warmth. Schmeling assisted Louis with money, and when Joe died in 1981 Max helped pay for the funeral. Much of the world came to believe Hitler's favorite boxer and America's great black hope had finally come to love each other.

DAVID MARGOLICK: We all love happy endings, and it's become convenient in a way to say that Joe Louis and Max Schmeling ended up as great friends. I don't think they were really great friends. I think they were barely friends, they barely knew one another. They spent only forty minutes together in the ring. ... but history tied these two men together... History brought Joe Louis and Max Schmeling together and in history they'll always be together...

CARD (archival): Joe Louis is buried in Arlington national cemetery, the resting place for those who have served their country with honor.

CARD (archival): Max Schmeling continues to live outside his hometown of Hamburg, Germany.