Billy Payne, Resident: Well, the winter of '27 it started raining early in the year that year. January, February, it rained it seemed like every day.

Sarah Percy, Resident: It rained and rained and rained and rained some more. It just looked like it would never stop.

Mildred Commodore, Resident: The river kept coming above flood level and it was rumored in all of the papers and things that if this levee would break we'd have a flood that would wash away from Memphis to New Orleans.

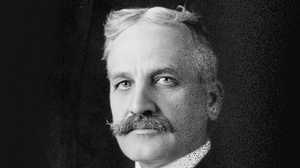

Narrator: On April 15, 1927 -- Good Friday -- as another violent storm battered Greenville, Mississippi, a party held in one of the town's finest homes. As the rain intensified, guests were drawn to the windows. Just beyond their view the Mississippi River was rising to unprecedented heights. A burst of thunder shook the house and the party fell silent. All eyes turned to one man-LeRoy Percy. The former senator was one of the most powerful planters in the Mississippi Delta. "Senator Percy," one woman asked, "will the levees hold?" Percy gathered a group of men and rushed to the levee protecting Greenville from the river. The levee was holding, but barely.

Staring at the angry water, Percy could see that an epic battle was looming-pitting man against nature. What he couldn't see was that a human storm was also approaching-one that would pit money against honor, black man against white, even father against son.

The people of the Delta fear God and the Mississippi, a saying goes. The river punishes with great destruction and rewards with great wealth. Floodwaters leave behind some of the most lush and fertile soil on earth. For half a century after the civil war, Delta planters had been richly rewarded by the river. By the early 1900's, they presided over one of the most productive cotton growing regions in the world. In an age when cotton was king, self-styled planter aristocrats ruled their domains like feudal lords.

The most ambitious of them all-was LeRoy Percy. His empire extended far beyond the cotton fields to the boardrooms of railroads and banks. As a prominent lawyer and businessman, he was determined to bring the plantation economy into the 20th century.

John Barry, Historian: LeRoy Percy saw the Delta as this great, bursting, industrial region. But the industry in the Delta was agriculture. That did not mean that it would be any less efficient than a Northern factory. It would operate with every bit as much efficiency. And of course the labor was the key to that.

John Tigrett, Resident: It was mighty easy to make a living with cotton. And you had the benefit of human labor there that was about as inexpensive as you could get. And these big plantations, they'd have thousands of these blacks that worked on there. I mean that you couldn't raise it without the blacks, without human labor there, you couldn't exist -- not only important, it was vital.

Narrator: The plantation system offered African-Americans work -- but very little else. Most families scraped out a living from sharecropping. The planters provided a small plot of land. Everything else was advanced on credit and deducted from the worker's share of the crop. It was a system ripe for abuse.

Mildred Commodore, Resident: It was known on some plantations that the only thing that the people would gather in life is what you would call three m's-meat, meal and molasses. And they would work from sun up to sun down and when the season was over the only thing they had left was an indebtment of $400-$500 -- something they couldn't afford. Because the white owners, see, during the time they had worked for the seed that season, they had used up all the meat, meal and molasses. But they had nothing, and when I say nothing, I mean nothing.

Pete Daniel, Historian: The planters looked at black people as workers. They looked at black people as people who should be willing and eager to work for them to produce their cotton and when they weren't eager they could be coerced.

Maurice Sisson, Resident: Well, I won't call his name, but there was a plantation owner that carried a bullwhip all the time and he spoke with that whip. And I seen him beat the blacks on Washington Avenue because they didn't get out of his way.

Narrator: Like his fellow planters, LeRoy Percy feared losing his black labor force. But unlike many, he believed, the best way to keep African-Americans in the Delta was to treat them fairly. Decency, Percy insisted, was part of the Southern code of honor.

Margaret Washington, Historian: The Percys had a sense of noblesse oblige. They thought of themselves as having more empathy with people of African descent. They saw themselves as being more understanding, more tolerant of them, more friendly with them, they saw themselves as being noblesse oblige incarnate.

Maurice Sisson, Resident: They were real business people. The Percys were real business people. They knew that their livelihood came from the blacks, so why destroy what makes you money? That's how I looked at it. So it was all business.

Narrator: In 1910 LeRoy Percy took his views on race relations and business to Washington, when he was appointed to a vacant Senate seat. A year later, Percy ran for reelection against a bitter political enemy. Former Mississippi Governor, James K. Vardaman, was a populist and an unapologetic racist. "If it is necessary," he warned, "every Negro in the state will be lynched to maintain white supremacy." Vardaman defeated Percy in a landslide.

Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Biographer: The effect of the defeat of 1911 on LeRoy Percy was to send him into the deepest gloom he'd probably ever experienced. He felt that he had let down the side so to speak, that his honor had been violated. Because not only had he lost the election, but he'd come in third. A sitting senator coming in third.

Narrator: Retreating to Washington County, LeRoy resumed his work and consoled himself with the diversions of a country gentleman.

John Barry, Historian: LeRoy was a classic man's man. Hunted, fished, played poker and he knew how to operate. He was not naive about anything. And as his son said, no one ever made the mistake of thinking he wasn't dangerous.

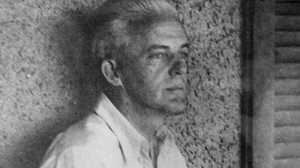

Narrator: LeRoy's commanding personality was altogether different from that of his only son and heir, William Alexander Percy. Soft-spoken and introspective, Will was ill-suited to the stringent code of Southern manhood.

Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Biographer: He felt himself an outsider, almost from the start. He worshiped his father. He thought he was the grandest man, and the most heroic that one could possibly have. At the same time, he thought I'll never be like him, and I should. It's my duty as a Percy to be as much like my father as possible, but he couldn't. It wasn't in his nature.

John Barry, Historian: He was smaller, physically. He saw no pleasure whatsoever in hunting or fishing. Would never go on these trips, even as a young boy he wouldn't go with his father. He was a poet, uh, and he was he was gay.

Narrator: Will had tried to live up to his father's expectations. He went to Harvard, earned a law degree, served with valor in WWI, and joined his father's law practice in Greenville. But, in his own mind he never measured up.

"It was hard having such a dazzling father," Will recalled, "no wonder I longed to be a hermit." Will often walked alone on the levee, his thoughts turning to poetry.

"What I wrote," he explained, "seemed more essentially myself than anything I did or said."

Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Biographer: Will Percy wrote a piece called "Falling Leaves." And he wrote about how he was walking along the riverbank and he says, "I know it is Fall because I am loneliest now. I go home to my family and I see my mother pacing up and down, and my father saying hush, don't say those things." It's a very moving piece of writing, but uh, it indicates how he recognized his parents' dissatisfaction with him, and his inability to do anything about it, and even to speak of it was impossible.

Narrator: Despite his feelings, Will continued to live in his father's house on Percy Street-placing the family empire above his own happiness. In the spring of 1922, that empire would come under direct attack. The Ku Klux Klan was gaining ground throughout the country. Klan supporters dominated the state governments of Colorado and Indiana. They helped elect the governors of a dozen states. By the 1920's, the Klan had swept over the Mississippi hill country and several counties in the Delta. They now challenged LeRoy Percy in his own domain. Percy despised the Klan. They attacked those closest to him. His wife was a Catholic. His business partner -- a Jew. His empire dependent on black labor. When he learned of a planned Klan rally in Greenville, LeRoy decided to fight back. On March 1, 1922 a tense crowd packed the Greenville courthouse. The Klansman spoke first.

John Barry, Historian: The Klansman starts out with his usual spiel. He's against the Catholics, the Pope's got this plot here, the Jews are doing that, the blacks are a threat to Southern womanhood -- it was a rousing speech. It had never been opposed.

Narrator: Will watched his father step up to the podium. No one knew what to expect.

John Barry, Historian: He starts out with humor. He goes on to say that he's got a partner who's a Jew, and he agrees that the Jews need to be held in line because he points out, that his Jewish partner had loaned $150,000 to people who had lived in Washington County at below market interest rates. And Percy had a real problem with that. Uh, so all of a sudden he's got the audience laughing. And he starts mocking the Klan. In the end however, he gets serious.

Narrator: "I know the terror the Klan embodies for our Negro population" Percy declared, "and I am here to plead against it. We have feasted together at the weddings of our young people. We have stood together around the graves of our loved ones. We have stood together and undivided."

John Barry, Historian: And he asks even the Klansman, he said, we want you to come home, come back to this community, leave the Klan. Uh, it was just a tremendous speech.

Narrator: "At the close of Father's speech," Will wrote, "the crowd went wild-shouting and cheering." That evening, they passed a resolution condemning the Klan.

Tony Dunbar, Author: This didn't happen anywhere else in the South. That the leadership of a rural community would stand up and confront and defeat the Ku Klux Klan at that period is unprecedented.

Narrator: "Our town was saved," Will wrote, "righteousness had prevailed." LeRoy's victory had brought the Percys closer together -- uniting them with a sense of honor and purpose.

But the Mississippi River would soon threaten Greenville and test the bond between father and son.

In the autumn of 1926 violent storms pelted the northern United States engorging streams and rivers. The arteries drained south funneling the waters of a continent into the Mississippi. By March 1927 huge swells reached the top of the Delta. Greenville was only a hundred miles down-river.

John Barry, Historian: Just imagine a force that's more than a mile wide, maybe a hundred feet deep and it's moving at nine miles an hour. Think of what's behind that. Clearly, it is something to be feared. I mean it's the greatest geological force in the United States.

Narrator: It was a force the Army Corps of Engineers thought it could control. The Corps had built levees, some four stories high -- on both banks of the river -- running the 1,100-mile span from Cairo, Illinois, to New Orleans.

John Barry, Historian: If you looked at these levees at low water, they looked like great, impregnable, fortresses. In 1926 for the first time in the official report of the Army Engineers, they say that they are now in a position to prevent the damaging impact of floods on the lower Mississippi Valley. Classic hubris.

Narrator: April brought record downpours. By the middle of the month, the first government-built levee crumbled in Dorena, Missouri. The surge of water pushed south bursting more levees, flooding more than a million acres of land and leaving 50,000 people homeless. The Delta was next.

Pete Daniel, Historian: So here comes this crest down the river at such a volume that some rivers are actually backing up because the Mississippi is so full of water that, for example, the Arkansas River, it starts flowing backward because the Mississippi is so high it pushes it back. So that's the kind of water we're talking about, this enormous amount of water coming down the river.

Irene LeLouis, Resident: When that river gets to the top of the levee is lapping over, it is guarded. Arkansas people guard the levee against Mississippi people; Mississippi people guard the levee against the Arkansas people. Afraid somebody will blow the levee and turn the water loose on the other side. If I blow your side of the levee, you're going to get washed off of the face of the Earth and I'm going to stay dry, because the water didn't come my way. It went your way.

Narrator: The wall of water kept pushing south. Levees began to collapse along the Arkansas River. It was already the worst flood on record and it was aiming all its force at Greenville. In desperation, Percy and his fellow planters pulled their workers from the fields to do battle with the river. They became part of an army of 30,000 men, including convicts, who struggled to raise the height of the levees with rows of sandbags. Still, the river continued to rise. When even more men were needed on the levees, Greenville's police resorted to force.

Mildred Commodore, Resident: They started going through Greenville and taking all of the black men -- this is another thing that I can remember so plainly -- all of the black people, even kids out of school, to go and protect the levee and almost man for man or boy for boy the whites had guns on and the others had nothing but picks and shovels.

Maurice Sisson, Resident: Shotguns, they just herded them up and drove them to the levee. Right down Nelson Street, that was the Negro drag at the time and they just got them off the streets and just carried them right down to the levee, started them to work.

Narrator: White residents began to panic. Those who could afford it boarded trains leaving the region. Upriver from Greenville, at a great bend in the river -- the Mounds Landing levee was showing signs of trouble. On Good Friday, the Delta was battered by the most savage storm of them all. As much as 15 inches of rain fell in 18 hours. One resident recorded in his diary, "Heaven spare us!" The Mounds Landing levee was beginning to crumble.

Pete Daniel, Historian: It's cold, damp, raining. The break is increasing. The water's washing over top of the levee and, according to some accounts, the-the levee starts feeling loose.

John Barry, Historian: The water started rising an inch an hour. That's fast. That's two feet a day. There is a limit to how high you can build sandbags.

Billy Payne, Resident: They didn't think it was going to hold. In fact, it was getting worse by the minute. They throwing all the sandbags in there they could, and it just, but it just kept getting bigger and bigger and they couldn't stop it.

John Barry, Historian: The men working on the sandbags know full well that there's no way that this thing is going to hold... and they start to abandon their position, and the national guard officer orders rifles held on them and threatens to shoot them if they leave.

John Tigrett, Resident: And these fellows were filling their sacks with sand. And my stepfather, he noticed that at the bottom of the levee some water started coming out. And he grabbed my hand. Grabbed my arm I guess and he said, run Johnny boy. Run for your life.

John Barry, Historian: And the levee starts shaking and rumbling. And men start running and all of a sudden, a big section of the levee, several hundred feet wide, just sort of pushes out, and carries men with it.

John Tigrett, Resident: You could hear them screaming, yelling, blood curdling levels. And uh, they were gone. See, you let the Mississippi out, and uh, you could almost hear it yelling. It's free. I'm free again. And man it came out with a roar. Oh. My step-father said to me, God damn, now remember Johnny boy, you'll have a lot of close calls in your life, you're not going to have any closer one than this one tonight.

Narrator: The break at Mounds Landing released more than double the volume of Niagara Falls. It flooded an area 50 miles wide and 100 miles long. It put water over the tops of houses in Yazoo city -- 75 miles away. The deluge was cascading south through the cotton fields of Washington County. It was only a matter of hours before the water reached Greenville-inundating the city from the rear. LeRoy Percy now faced total disaster. The river was seizing his empire. Up in his room, LeRoy's son was writing poetry. Will had been working feverishly through the night. "I was in a writer's tantrum," he would later confess. The water rolled towards Greenville, wiping out whole forests and farms.

Maurice Sisson, Resident: It was a sight to see, there's no doubt about it. It's hard to describe. It's just...it just had a force to it. It was just (MAKES NOISE).

Josephine Thomas, Resident: Oh, my Lord. It was coming from every which way. I was so scared. I didn't know what had happened. I'll tell you the truth. Come late that evening, you couldn't see nothing but water, and you had people hollering, you know scared and running every which way, you know. And people get in their boats and things and go searching for them.

David Cober, Resident: When it got light enough for us to see, you could see horses, cows and dogs and everything else, right in that water, drowning. I thought we was all going to drown.

Narrator: The flood finally reached Greenville in the early morning hours of Friday, April 22.

Sarah Percy, Resident: I looked up and said, oh, I see it coming. It's coming. And it was creeping into the gutters. But it was coming fast. Not heavy waves, just seeping in, but I tell you, seeping in a hurry.

Narrator: Ten feet of water inundated downtown. The current at the intersection of Broadway and Main turned deadly.

Maurice Sisson, Resident: You could just see the livestock floating dead in the waters. You know young children at that time knew everybody's horse and everybody's cow, you'd say, there goes Mr. Fowler's cow, there goes Mr. Williams' horse, you know just bloated and floating.

Narrator: Some residents found safety in the upper floors of stores and churches. Others clung to rooftops. Anyone with a boat was pressed into service.

John Tigrett, Resident: I had a sea sled at that time with about a 25 or 30 horse power motor and I became a rescue captain. Which was a great event for me at that time, fourteen. And so every day we had assigned certain routes, and we'd go out, pick these people up and bring them back to the high grounds and keep going on my route.

Well I saw these three people. Two kids and what I thought was a very fat black woman on top of a cotton house. She got in. She said, fore god that child my baby's coming. And I said what did you say? She said, I said fore god my baby's coming. Well I said, can you just wait. It'll only take forty minutes to get to get you to the high ground and they'll look after you. She said no. She said he's coming now. And I thought what in the world. What I do? And she said don't worry, said just be real gentle with it. Said just take his head and pull him slowly, and said he'll come on out. I'll push. And she pushed, and I pulled, and here was a little baby boy. I then dipped him in the Mississippi River floodwater and uh, hit him a couple times, and he started crying. And she says give him to me, I'll take him on my breast, and she lay down, she's still in the dirty water, and she took this baby and put him on her breast.

Well, I think I cried. That's all I remember. Uh, my first experience at being a midwife. Anyway, I untied the boat and when we got close to the high ground I hollered I said look I've got a new baby, just born, got the mother up, and as she stepped out of the boat, she turned to me and said what's your name son? I said John. She said, I'm going to name this baby John. That's the last I saw of her. An amazing woman. Bless her. Amazing woman

Narrator: "For 36 hours the Delta was in turmoil, in movement, in terror," Will wrote. "Then the water covered everything, and a great quiet settled down."

"Father looked somberly over the drowning town," Will noted. "He was tired."

But there was work to do. LeRoy immediately began raising money for his devastated community, and appointed his son head of the flood relief committee.

The task before Will was enormous. Up until now, Will was known only for being his father's son. Now at age forty-two, he would have the chance to prove himself worthy of the Percy name.

Within days, the deluge had covered 27,000 square miles, an area the size of four New England states. "The flood," one preacher said, "had spread as wide as God's arms." More than a thousand people were dead. Washington County was hardest hit. The water washed away 7,200 buildings; damaged or destroyed thousands more. It displaced tens of thousands of people.

Josephine Thomas, Resident: We lose a few clothes and furniture. We lost everything we had. What little we had. Ain't nobody had too much, but you know whatever it mean a whole lot to you because you ain't had nothing else.

Narrator: As the rescue efforts expanded, rowboats and skiffs followed power lines to farms and houses.

Many whites were evacuated from the region. Blacks were rounded up from the countryside and deposited on Greenville's levee -- a narrow island of high ground with the river on one side, and flooded land on the other.

Two days after the Mounds Landing break, more than 10,000 refugees crammed the eight-foot-wide crown of the levee- in a line that stretched over five miles.

Pete Daniel, Historian: There were no tents to start with. It was just a few blankets to start with. You can see them stretching across a little frame to try to make a tent-like place to stay out of the weather, which was really bad. It was April. It was rainy. It was cold. These people had been out in rescue boats. It was miserable.

The city's water supply was contaminated -- its food supply destroyed. With no sanitation facilities, the refugees were at risk for typhoid and cholera.

For Will Percy, there was only one honorable course to take. Evacuate the black refugees to safer havens down-river.

Will immediately called a meeting of the town's relief committee. Convinced that he spoke for his father, the committee agreed to Will's call for an evacuation order.

When a group of planters learned of the plan, they were furious. Afraid that they would lose their workers, they demanded that Will rescind the order.

The planters reasoned that if these people ever got away, they may never come back. They wanted to ensure that they had laborers to try to finish out their cotton crop if the water went down that year.

This was a perfect example of that mentality that Mississippi planters had. It didn't really matter if these people were uncomfortable. It didn't really matter if they were starving. It probably wouldn't have really mattered a whole lot if a lot of 'em had died for one reason or another. They were gonna keep their laborers and that's just ruthless contempt for human beings.

Narrator: Will was appalled by the planter's demands, and refused to budge. Undaunted, they took their case directly to his father. The next morning, LeRoy Percy went searching for his son.

John Barry, Historian: LeRoy finds Will on the levee. It's a war scene. There are refugees everywhere. They begin to take a walk. LeRoy is suggesting gently that perhaps evacuation was not the best decision to make. Will is saying it's the only decision. LeRoy disagrees. Will is stubborn, insists, there is no way he could do anything else.

Narrator: While they are talking, 500 white women and children are loaded on one of the barges and the loading of the blacks has begun. Steamers and barges had come from all over the river. There are enough steamers essentially to evacuate the entire city in a day. The captains are told to stand by. Finally LeRoy gets out of Will one concession, that he will meet with that committee once again to discuss the decision before everyone is loaded.

Then, without Will's knowledge, LeRoy approached each member of the relief committee. He too, feared that an exodus of blacks would prove disastrous. His son, he said, had spoken only for himself.

When the committee reconvened a few hours later, they dealt Will a stunning blow. To a man -- the members now opposed the evacuation.

John Barry, Historian: Although he does not admit it he had to know right then at that moment that the only way this committee reversed himself, was because his father had betrayed him. Had betrayed him personally. Had chosen Washington County and the empire he had built over his son. The evacuation is canceled; the steamboats that are standing by leave empty. Every captain absolutely infuriated, over the waste of time and resources.

Narrator: For Will, it was a wrenching moment. Ever since he was a young boy, he had tried to live up to his father's ideals of honor and decency. Now those principles seemed to have lost their meaning.

The next day, April 26, an emissary from the federal government was on his way to Greenville. Secretary of Commerce -- Herbert Hoover. He was in charge of coordinating what had become the largest rescue and relief operation in the nation's history.

There were 600,000 refugees in the flood region. Food, supplies, and medical care would come from the Red Cross, which was setting up tent cities on high ground.

By the time Hoover arrived in Greenville, he was expecting to see an evacuation underway. But when he met the younger Percy on the levee, Will proposed a completely different plan: Greenville would become a Red Cross distribution hub. The blacks on the levee would provide the labor. Hoover approved the new plan, then left town.

For the whites who remained in Greenville, daily life was settling into a dreary routine. A boardwalk was built throughout the downtown area. Some merchants opened up their doors for business.

For African-Americans, life was very different. The lucky few found shelter in towns. Most others were herded into tent cities patrolled by the National Guard.

David Cober, Resident: You were on the levee and you stayed on the levee unless you got a pass to be able to go in to town. You had to have a tag on you. You was tagged. When you got ready to give you a shot, you had to get another tag. Your chest was full of tags. You don't go nowhere unless you got permission to go. You had to have a tag on you. And it was just...it was really slavery.

Narrator: Some guardsmen began to abuse their power. Reports spread of beatings and rapes in the tent cities. Blacks outside the camps were infuriated, but powerless to help.

David Cober, Resident: My own brother come down there to see about us, but he couldn't come in the camp. So I went down in the bushes to see him. While I was down there. One of them soldiers walked up on me, get up. Put the pistol on me. And my brother had a pistol too. Now my brother wasn't a refugee, but my brother put the pistol on him and made him leave me alone. And of course my brother hit the road, went on, came on back to Greenville. But it was some awful times.

Narrator: A week into the flood, life in the camp was becoming unbearable. Beyond the lines of tents, thousands of starving livestock shared the narrow stretch of levee. Dead animals were thrown into the foul water. The stench was overwhelming. When the first Red Cross supplies arrived in Greenville, they were not distributed on the basis of need.

Mildred Commodore, Resident: The whites would take it, take what they wanted or give it to who they want, and naturally the whites had better means of getting it.

Maurice Sisson, Resident: First come first serve with the whites. Blacks, they were at the end of the line. They got whatever was left. Sometime there was nothing left.

Narrator: The National Red Cross grew concerned about Will's leadership and launched a secret investigation into profiteering and theft in Washington County.

John Barry, Historian: Will lost control of the situation. There were ultimately 154 refugee camps run by the Red Cross. Greenville, Mississippi became the single worst refugee camp of 154.

Narrator: LeRoy Percy was not there to help his son. He was crisscrossing the country trying to rebuild the Delta's finances. "To falter or fail now, he warned, "would mean the abandonment of an empire."

In June, two months after the Mounds Landing break, the flood finally started to recede. Some residents began returning to their homes.

More and more boatloads of Red Cross supplies were now arriving on the levee. Will desperately needed laborers to unload the cargo. Once again, city blacks were pressed into work gangs.

Maurice Sisson, Resident: They forced them into service and I think they could have gotten enough without it. But that was the only way they knew, and that was the quick way to do it, by force.

"I became a dictator," Will recalled. "But the consciousness that my judgements were often wrong was a continuing nightmare."

John Barry, Historian: There's all this internal hostility. He could not take this frustration out on his father. Will had been humiliated, and in his humiliation he began to humiliate uh, the black men and women and children on the levee and there was no place else for this frustration to go.

Narrator: An influential black newspaper proclaimed that Will Percy's prejudice against blacks "is as bitter as gall."

Two-and-a-half months into the flood, racial tensions came to a boil.

John Barry, Historian: There was one black gentleman who actually had just gotten off the levee after working all night. He had gone back to his house to sleep. The police were going through the black neighborhoods, going looking for men to bring back to the levee. A police officer went up to this gentleman on his porch and told him to get into the truck.

Mildred Commodore, Resident: He told him, "You get up and go to work." And the answer was, "No. I've been to work." So he says, "You're supposed to work. Go when I tell you." And the man got up to go in the house and he shot him down on his front porch. And I don't think it was a black person with dry eyes in that town.

John Barry, Historian: All of a sudden in Greenville the whole city is electrified, incredibly tense over all this. Uh, there is real fear in the white community that, who are vastly outnumbered, that there is going to be a race war.

Narrator: Will Percy marched into the center of the storm. He called a meeting of the black community at a local church. When he arrived, the church was empty. One at a time, the black leaders began to enter. Amid an uneasy silence, Will rose to the pulpit. The quiet poet suddenly transformed himself into an angry preacher.

"You sit before me sour and full of hatred," Will declared. "You think I am the murderer. I am not the murderer. That foolish young policeman is not the murderer. The murderer is you! Your hands are dripping with blood."

Margaret Washington, Historian: It was the most amazing speech that he could have made to the African American community. After all they had endured, after all the work they had done. He told them that the city of Greenville had done them a great service. The city of Greenville had saved them, and how did they pay people back? They paid them back by being lazy, being indolent, and refusing to work.

Narrator: He demanded that they all get on their knees and pray to God to forgive them for the murder of that poor black man. If you're going to keep your heel on the neck of thousands and thousands of people, and keep them as downtrodden laborers, ultimately you can't be nice about it. And that's what LeRoy Percy knew when it came down to it. And that's what Will Percy was finding out, and going along with. The fragile bond between the Percys and Delta Blacks was broken.

"Our people have the most troubling road to travel," LeRoy Percy wrote to a friend. "Some will be able to make it. Many, broken and discouraged, will fail." In a year and-a half Leroy was dead-his dream of empire swept away with the torrent of water.

Shortly after his speech at the church, Will Percy resigned as head of the Greenville Relief Committee. The following day, he left the Delta for an extended trip to Japan.

He would return to Greenville to rebuild his father's plantation. There, Will would live and die in the house where he was born. He would never write poetry again.

For many African-Americans, the flood of 1927 marked the end of an era and the start of a journey. As the Mississippi River finally retreated to its banks, they began heading north.

Mildred Commodore, Resident: When you go North, there were chances of work, you know, getting something. If they had remained there with cotton 50 cents a pound and meat, meal, and molasses, how long could they have existed?

Maurice Sisson, Resident: So many people wanted to leave here to go to Chicago. I believe some of them rode free so many got on the trains. In Greenville you had the train was at ground level, and they were pushing to get on the train. I surely wanted to go to Chicago. Everybody was going but me. They just knew they were going to the promised land.

Narrator: A great river of humanity was flowing out of the Delta. Within a year of the flood, tens of thousands of sharecroppers would turn their backs on the planters of the Delta. The exodus LeRoy Percy had feared so long could not be stopped.

Fatal Flood

Fatal Flood