Adolphus W. Greely (Tim Hopper): "We have been lured here to our destruction. We are 24 starved men; we have done all we can to help ourselves, and shall ever struggle on, but it drives me almost insane to face the future. It is not the end that affrights anyone, but the road to be traveled to reach that goal. To die is easy; very easy; it is only hard to strive, to endure, to live. Adolphus Greely."

Narrator: "I will bear true faith." Every officer in the U.S. Army swore the oath to his country, but Lieutenant Adolphus Greely embodied it. He and his 24 men were about to leave the world behind and travel to the farthest reaches of the Arctic. There, they would take part in a revolutionary scientific mission, and explore the limits of the known world. It was everything Greely could have asked for.

Jim Lotz, Writer: There was fame to be gained. There was glory to be gained. And he had this very, very strong drive to make himself exceptional so that he would be recognized by the military.

Narrator: The military had been Greely's salvation. As a child he had seen his father crippled and his mother's life drained away in a Massachusetts mill town, and he wanted none of it.

He had escaped by volunteering for the Union, had survived the bloodiest fighting in the country's history, and led one of the first units of black troops. The Civil War left him with a deep devotion to the Republic that had rescued him from obscurity. He reenlisted in the peacetime army, and soon found himself expanding the telegraph network out west.

It was there that Greely found his calling. For the first time ever, man was beginning to unravel the mysteries of the weather, by using the telegraph to track it over hundreds and thousands of miles. Greely was captivated by the study of the earth's climate, and by the belief that the key lay in the Polar Regions. When he heard talk of an Army expedition to the Arctic, he gave his life over to it. He spent years poring over scientific treatises, cultivating patrons, and studying accounts of earlier expeditions. And now, at last, here was a chance to truly make his mark in the world.

Adolphus W. Greely (Tim Hopper): "July 7, 1881. At 12:15 pm, St. John's time, our voyage commenced. We started off under the brightest of skies, with the finest of weather."

Michael Robinson, Historian: This was not simply some new Arctic expedition. This was really an attempt at a new science of the world. It used to be in the 1700s that people would collect things and put them in cabinets of curiosity and try to identify and label what they were. But scientists in the 19th century realize that they need to understand how the parts fit together. And it's really through that, that people like Darwin are able to come up with his theory of evolution. That holistic sense of science is really catching fire. And so in a sense people begin to envision the earth almost like an organism with a set of circulation systems. And the key to understanding this system was the Polar Regions.

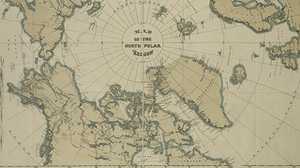

Narrator: A coalition of scientists had enlisted the governments of 11 nations in an unprecedented quest to understand the earth's climate. Called the First International Polar Year, it would create a chain of 14 stations around the Arctic, at which observers would collect synchronized meteorological, astronomical and magnetic data.

Michael Robinson, Historian: The hope was that this would offer the key to a new climatic understanding of the world. That's what the stakes were in this expedition.

Narrator: Greely and his men would establish the northernmost station on the shores of Lady Franklin Bay, just 600 miles from the North Pole.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: The trip up was amazingly easy. Given the time of year they should have encountered heavy pack ice which would have impeded their trip and it didn't. They were able to move up there rather quickly.

Narrator: The real surprise was the ease with which they ran the narrow stretch of water between Cape Sabine on the coast of Ellesmere Island, and Littleton Island on the Greenland side. The few whalers that ventured this far north often found the passage choked with ice that drifted south in the summer.Greely's orders were precise, but they took little account of the vagaries of the ice. At the end of the first year, the plans called for a ship to re-supply the station; at the end of the second year, another ship would sail north to bring them home.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: One of the organizers had recommended that they not have their own ship; he felt that ships were "cities of refuge" that made explorers timid. So almost unique among polar expeditions, they didn't have a ship with them.

Narrator: On August 26th, 1881, the whaling ship Proteus sailed out of Lady Franklin Bay, leaving 25 men and 350 tons of supplies in one of the harshest environments on earth. They were on their own, with no connection to the outside world.

Greely was relieved: "I am glad the ship has gone," he wrote, "it settles the party down to its legitimate work." He had complete faith in his orders, in the United States Army and, above all, in himself.

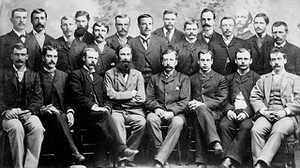

Greely was even more isolated than he knew. He and his men had few supporters back home. Most congressmen believed that the government had no business funding scientific endeavors. As for the Army's senior command, the whole affair was a pointless distraction from the Indian Wars in the West. In the end, a small band of enthusiasts had secured funding for the expedition from a lame-duck Congress. Greely's mission was an orphan, and it showed. The Army had held up its start, leaving the lieutenant just a few weeks to recruit his men. They had been drawn from a small pool of Army volunteers; none of the soldiers had ever been north; few had even been to sea. In fact, most were cavalrymen -- only weeks before they'd been stationed at outposts across the Great Plains.

Jim Lotz, Writer: I think some of them figured they when they were up there they can make their stash and come back and have a pocket of money because they would be paid but they would have no expenses up there... nowhere to go.

Narrator: Whatever their reasons for being there, some of Greely's men were already distinguishing themselves. Twenty-five-year-old Sergeant David Brainard set a fierce pace for the men as they raced to build the outpost they named Fort Conger.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: Brainard had a sense of adventure that many of the other men didn't have. But he understood orders. An order was an order with David Brainard.

Narrator: George Rice, a 24-year-old photographer from Nova Scotia, lacked Brainard's military training, but he did share his sense of adventure.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: Rice was not only the photographer on the expedition, but if anything had to be done Rice was volunteering to do it. And he did it exceedingly well.

Narrator: The Greely expedition itself was adventure enough for most men, but Brainard and Rice were both drawn to a still greater challenge -- beating the record for Farthest North, a title that the British had held since 1607.

Michael Robinson, Historian: In the late 19th century it was very difficult to get funding for projects like Greely's project. It wasn't clear how this pure polar science would help Americans back home. The federal government wanted payoff. They wanted something snazzy. And so the American expedition had a secret agenda, which was to try to reach as far north as they could, to at least beat the British record.

Narrator: This would be Greely's crowning achievement -- a nation devoted to the mastery of nature would surely honor the man who brought home the prize. But for now all that would have to wait. Winter was closing in.

George Rice (Justin Mader): Thermometer range from -44.0 to -56.4, observed and corrected.... A still lower temperature today, from -47.2 to -57.2....

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: At those temperatures pee freezes before it hits the ground, and even your breath condenses into little crystals that snow down and fall on your sleeve. So it's a really strange environment.

Jim Lotz, Writer: Oh, it's a wondrous place. Just so huge and so uncaring and so vast in that very, very real sense that makes you feel so insignificant. There is this real sense in isolation that you're in touch with something that's infinite, enormous, something that is beyond human ken, beyond human understanding.

Narrator: As winter tightened its grip, Greely and the senior men kept up a rigorous routine: 500 measurements a day of wind speed, barometric pressure, magnetism, and dozens of other phenomena.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: It had to be done and it had to be done at regular hours, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. And if it was 60 below zero and the wind was blowing at 90 miles an hour you still needed to go out and gather that data.

Narrator: For the enlisted men, winter enforced an idleness that was no less challenging.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: The most striking thing about an arctic winter is that it's totally dark. You've got essentially five months of pure light where the sun never sets, five months of dark, where the sun never rises. There's not a lot to do. Greely forbade his men from lying down during the day, so they would sit at benches arguing.

Jim Lotz, Writer: The whole atmosphere began to change as the winter got darker and darker and colder and colder.

Narrator: At the age of 37, Greely had been commanding men for half his life. But in the isolation and confinement of Fort Conger, the strict discipline he had learned in the Civil War only stirred up resentment. When Greely ordered his hard-bitten cavalrymen to tend to the officers' needs — including their laundry — some of the men took exception. Even David Brainard was stunned by Greely's response.

David Brainard (Rich Porfido): "A long talk was given to the crowd of angry and excited men by Lieutenant Greely, who said that he was not a man to be trifled with and in case of necessity he would not stop at the loss of human lives to restore order."

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: What commander is thinking of the final solution that early in the game? That's just being an insecure commander, uncertain with how to wield authority without clubbing your men over the head with it.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: It began to grate on the men very, very soon. And that began, I think, the breakdown of discipline within the group.

Narrator: The isolation affected everyone. In letters to his wife Henrietta -- letters that he could only store away until the relief ship arrived -- Greely gave voice to doubts and longings that he carefully concealed from the men.

Adolphus W. Greely (Tim Hopper): "It would never do that the commander should show signs of homesickness. But I miss you so much, my darling, and want you so much."

David Shedd, Greely Descendant: She must have seen something in him that he didn't express normally to other people. Judging just from these love letters it was obvious that he would do anything to sort of keep her attention.

Narrator: As the only daughter of a bank president, Henrietta had grown up in wealth and comfort. But there was steel behind the soft exterior -- "she likes to have her own way," Greely said fondly. Henrietta had resisted Greely's Arctic dreams from the first. "Are not your ambition and pride guiding you," she had asked, "to the exclusion of all other thought?" But Greely never relented — not then, and not now.

Adolphus W. Greely (Tim Hopper): "With all my yearnings for you I cannot bring myself to regret coming. I shall at least have made my mark in the world. To do what one has set his ambition on causes a vast deal of pain, sorrow and privation."

Narrator: By March the camp had been awakened by the returning sun, and the entire crew galvanized by their next challenge: beating the British record for Farthest North. Greely offered that challenge to two teams who would vie for the prize. George Rice headed up the Ellesmere coast with one team, while David Brainard joined the other on the Greenland side.

After four weeks of hardships and setbacks, Rice and his companions had to turn back, empty-handed. But Brainard was engaged in the adventure of a lifetime.

David Brainard (Rich Porfido): "May 13th 1882. We have reached a higher latitude than ever before reached by mortal man. We unfurled the glorious Stars and Stripes to the northern breezes with an exultation impossible to describe."

Narrator: 83 degrees 23 minutes 8 seconds North. For three centuries England had held the honors, but no more. Brainard, Lockwood and Christiansen had traveled 60 days, covering almost a thousand miles in temperatures well below zero, through pain and snow blindness to within 455 miles of the North Pole. They had beaten the British record by four miles. At the new limit of the known world they flew a flag Henrietta had sewn, and carved the logo of Brainard's favorite beer into the rocks.

On the 1st of June, 1882, Brainard and his companions returned to a boisterous welcome from their colleagues, and from their grateful commander. With their victory secure the men settled back into the familiar routines, and explored the countryside as it was transformed by the ever-present sun. They looked forward to the relief ship; to new faces, letters from home, fresh supplies. But with each passing day, the tranquility of summer gave way to a growing uneasiness. By June some of the men could speak of little else. By the middle of July they had taken to climbing the hills to stare at the horizon. By the end of August they knew that the ship wasn't coming.

George Rice (Justin Mader): "All preparations for the ship's coming have ceased: we have accepted the inevitable conclusion. The worst is that the failure of the ship's coming this year has shaken the confidence of many in its coming next year. George W. Rice."

Narrator: The re-supply mission had been a lackluster affair, run by a lowly Army private. But not even the most experienced sea captain could have penetrated the wall of ice at the bottleneck between Cape Sabine and Littleton Island.

Jim Lotz, Writer: Morale plummeted, just went straight through the floor. All these fears that weren't present in the first year began to weigh very, very heavily upon the soldiers.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: The whole chemistry of the expedition worsens when the ship doesn't arrive.

Narrator: Through the long night, Greely pored over the contingency plans in his orders. If no ship had arrived by the end of the summer, these cavalrymen were to sail 250 miles over some of the most treacherous seas in the world in three tiny boats, make their way past the bottleneck of ice, and meet the ship at Cape Sabine. If the Army was unable to reach them there, it would leave a rescue party waiting on the Greenland side, at Littleton Island. The prospect terrified the men, and Greely's repeated declarations that he intended to follow his orders to the letter further poisoned an already dangerous atmosphere.

The mission to bring the Greely Expedition home didn't leave St. John's until June 29th — late in the sailing season. Once again, it was clear that the Army had other priorities. Once again, a group of Army men sailed north on the Proteus, led by a man who had never been to sea: Lieutenant Ernest Garlington. And, once again, they ran into the ice. But this time, Garlington insisted on pushing ahead, and ordered the Proteus into a narrow lead, overruling the objections of the ship's veteran captain. Within hours the ship was crushed and sent to the bottom of the sea, along with her precious cargo. Miraculously, Garlington's men all made their way to outposts on the Greenland coast over the next few weeks. By then, the traumatized survivors could think of nothing but getting home. The mission was abandoned.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: Garlington was supposed to over-winter on Littleton Island so Greely would at least have people nearby that could sled over to meet him. But none of that happened. Garlington just got the hell out of there.

Narrator: From the moment Henrietta learned of the Garlington disaster, she pleaded with the Signal Corps, with the Secretary of War, with the President himself, urging they make another effort in the last remaining days of the sailing season. Even if they couldn't reach her husband, at least they could leave a rescue party at Littleton Island. "Mr. Greely," she reminded them, "expressed to me complete faith in the government's care for its own expedition."

The response was slow in coming. "The Secretaries of Navy and War," it read, "concur that nothing can be done this season to reach Mr. Greely. He will be reached next year as early as possible."

Susan A. Kaplan, Anthropologist: At Fort Conger they had everything they needed. They had a wonderful station that was warm and secure. There was ample game. They could have lived there for years, probably unhappily, but they could have lived there for years.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: It just made absolutely no sense to leave Fort Conger. Many of the men wrote in their private diaries that this was absolutely foolish. It was insane to do this.

Narrator: At three o'clock on the afternoon of August 9th, 1883, Sergeant Brainard shuttered the doors at Fort Conger, and hurried to join the crowd of sullen, fearful men waiting in the boats. Greely had ordered the abandonment of Fort Conger, and Brainard dutifully carried out his orders.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: Greely was a serving lieutenant in the United States Army. He took his orders and he did what he was told to do. Unfortunately, the orders were written by someone who had absolutely no idea what was going on in the Arctic.

Narrator: No sooner had they sailed into the ice-choked waters beyond Lady Franklin Bay, than Greely started to fall apart.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: I don't think Greely knew what to do, literally did not know what to do at that point.

Jim Lotz, Writer: He started to blow his top, threatened to shoot some of the soldiers. He was lost.

Narrator: Greely teetered on the brink, raging at the men one moment, and then disappearing into his sleeping bag for scandalously long stretches. Brainard saw Greely's hold over the men vanishing.

David Brainard (Rich Porfido): "The C.O. is seldom out of his bag. His appearance indicates the most abject cowardice.... The men don't lose sight of the gross ignorance and incapacity of the man who brought them to this present strait."

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: We're all forged to a certain extent in adversity. Our personalities really define themselves in adversity, and people like Rice and Brainard were showing what they were made of.

Jim Lotz, Writer: Rice had some experience of boats. He spent some time in boats in Cape Breton. He was up on the bow looking for the leads ahead. He became a navigator. And he was very, very highly regarded for this role. He fell overboard about four times and they pulled him back in. He said, "Well I've had more baths than you guys have had all year."

Narrator: Despite Rice's leadership they were barely moving, and they were running out of coal.

One week after leaving Fort Conger, Greely told his officers that he was considering abandoning the steam boat and loading their supplies onto an ice floe, trusting the currents to carry them south. Like most others, Brainard desperately wanted to turn back and winter at Fort Conger. Greely's plan was "insanity," he wrote, "and if my opinion is ever asked I shall tell what I think."

It wasn't, at least not by Greely. That night, as Greely slept, three men approached Brainard with a plan. The expedition's doctor would declare Greely insane, and another officer would lead the men back to Fort Conger. Brainard was the key to the plan -- the men would follow their first sergeant. He was, in short, being asked to lead a mutiny.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: But Brainard was a very straight man, and although he had joined the Army very casually he took its precepts seriously.

Narrator: If they got rid of Greely, what then? Freed from the restraints of military discipline, how would 25 men fare in a lawless wilderness over the coming winter, or two, or three? For Brainard, a collapse of discipline meant certain disaster; he would have no part in it. Without Brainard's support, the conspiracy fell apart.

David Brainard (Rich Porfido): "We have crossed the Rubicon, and to turn back now is out of the question. We must advance, although I am fearful it will result in disaster."

Narrator: Two weeks after they left Fort Conger, the ice seized up. With the steamboat hopelessly trapped, Greely no longer had any choice. Reluctantly, the men dragged the supplies and their two fragile whaleboats onto an ice floe. Now they were at the mercy of the winds and tides. Greely's officers seethed with anger, but they agreed with him on one point: the scientific records would not be left behind.

Michael Robinson, Historian: As the men begin to contemplate that they may not return home, then suddenly leaving behind some kind of legacy for all this pain and suffering becomes more important. Their impending death gives this greater meaning.

Narrator: And so they drifted. Days went by, and weeks. Storms battered them mercilessly, until they huddled on a piece of ice barely large enough to hold them. Then, suddenly, after 51 days at sea, and with only a few days of pale sun remaining, Greely and his men washed up on the rocky, barren shores near Cape Sabine.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: They all should have died. It's amazing that they didn't all die.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: It's a piece of rock spat out from hell and allowed to cool. It's red granite, very little grows there. The muskox and caribou that they would've got further north at Fort Conger don't go there. It's a horrid place.

Narrator: Despite the bleak surroundings, Greely's men soon discovered a surprising source of comfort: their commanding officer. Adrift at sea, Greely had cowered in his sleeping bag; back on land, he was cool headed and effective. He led the effort to build a shelter in the gathering darkness, and dispatched missions to find caches of food. After 51 days of helplessness on the ice, his men now welcomed a sense of order. For the first time since the expedition had begun two years earlier, they saw in Greely their only chance of survival.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: They almost began to understand why it was necessary to have that military command that he had been talking about for the previous several years. If they didn't work together, if they didn't obey what Lieutenant Greely said that they needed to do they were all going to die.

Narrator: Greely was stunned at the barrenness of their surroundings, but he took heart from the thought that they had made it to within reach of safety.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: Greely believed that there were rescuers who were spending the winter on Littleton Island on the Greenland side, and that by the time spring came they would be rescued, and there'd be a lot of help coming.

Adolphus W. Greely (Tim Hopper): "The party are in very high spirit, feeling certain we can get through. I, however, am fully aware of the very dangerous situation we are yet in. I am determined to make our food last until April 1st."

Narrator: As the sun disappeared for the last time in 110 days, the men crawled into the dark, freezing hut they named Camp Clay. There was scarcely room to lie down. But the crowding, the darkness, the cold and all of their other afflictions would soon be eclipsed by one cruel obsession: food. Brainard was in charge of their meager provisions.

David Brainard (Rich Porfido): "This afternoon I opened a barrel of dog biscuit and found a large percentage entirely ruined. That which was thoroughly rotten and covered with green mold was thrown on the ground, and was eagerly devoured by the half-famished party. What, I wonder, will be our condition when we undergo a still greater reduction in our rations?"

Narrator: Greely tried to counter the despair with a careful system of rationing. But there was no escaping the simple truth: they needed more food, or they were going to die. George Rice had already led a series of searches, looking for stockpiles of food left by previous Arctic explorers. At the beginning of November, he led a last effort before winter closed in. Five days out he and his men finally came across 150 pounds of precious meat that had been stored away by an earlier British expedition.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: They were just trying to hurry there and hurry back. But hurrying, doing big miles with no sleep, probably no rest and no food or even water, it would've been very easy to get frostbite. And that's what happened to Ellison.

Jim Lotz, Writer: Ellison just collapsed. His hands and feet were frozen. And Rice, who was in charge of the party, had to make the decision either we take the rations or we take Ellison. And he decided to take Ellison.

Narrator: The survivors dragged their crippled, screaming companion across the frozen wasteland until they were all near the point of collapse. Rice summoned the will to continue on alone for 12 more hours to Camp Clay, and sent out a rescue party. Brainard led the mission. By the time they reached Ellison, he was near death.

David Brainard (Rich Porfido): "Ellison was a pitiable sight, with his face distorted and frozen, and his limbs ice-like and useless. I tried to cheer him, but he would repeat in a low, pleading voice, 'please kill me, won't you!' .... We at last reached Camp Clay at 2:10 am. Never before had rough bearded men evinced more sympathy and tenderness towards a crippled comrade."

Susan A. Kaplan, Anthropologist: These men were really extraordinary in the care that they took of one another.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: You're beginning to see the strong people become stronger, and the weak people become weaker. People like Rice and Brainard are becoming more than they were as a result of this trial by fire. But the real surprise is that Greely really came into his own when the chips were down.

Narrator: In this crucible of suffering Greely had been stripped of his vanities and ambitions, his iron will tempered with compassion. Drawing on the examples of Rice and Brainard, he cultivated an atmosphere of shared sacrifice, giving his rations to a sick companion, or taking on unpleasant chores himself. So when Greely ordered everyone's rations cut to provide extra for Ellison, there was no argument. "Lieutenant Greely has shown himself to be a man of more force of character and in every way greater than I had believed him to be," one of the men wrote. "I am very sorry not to have found out sooner his full worth."

Even as Greely won over his men in that third winter, he had come to grasp the unthinkable: they had been abandoned. There was no rescue party waiting at Littleton Island -- there would be no deliverance on April 1st, or May 1st, or June 1st. Even if the government did send another mission, it couldn't reach them before mid-summer.

Adolphus W. Greely (Tim Hopper): "No game, no food, and apparently no hopes from Littleton Island. We have been lured here to our destruction."

David Brainard (Rich Porfido): "Ellison's right foot dropped off this morning without his knowledge. The fact was carefully concealed from him. One of his fingers fell off a few days ago, and several others will follow in a short time."

Narrator: On January 18th the men gathered on a rocky hill that would become known as Cemetery Ridge. Officially, William Cross's death was chalked up to an obscure disease, but everyone knew the real cause: starvation. It was the expedition's first funeral.

George Rice (Justin Mader): "Ellis tells me of being intimidated by the other occupants of his sleeping bag and talks of cannibalism. I much fear the horrors of our last days here. George W. Rice."

Narrator: Rice drove himself past the point of exhaustion, seeking to ensure their survival. He gathered hundreds of pounds of tiny crustaceans that appeared at the water's edge in the spring. He tried to walk across the ice to Greenland to look for the rescue party, but was turned back by open water. Finally, at the beginning of March, he volunteered to take "Shorty" Fredericks to look for the meat they had abandoned when Ellison collapsed.

George Rice (Justin Mader): "There's a hard trip before Shorty and myself. I start tomorrow, although I am pretty well used up, weakened and hungry."

Narrator: As the sled was being readied, Rice's bunkmate died. Too exhausted to bury him, Rice crawled in beside the corpse for a few hours' sleep, and then headed out with Fredericks into the half-light. Just a few hours out, Rice and Fredericks were forced to hide in their sleeping bag as a gale battered them for 22 hours. When they were finally able to leave their encampment, Fredericks noticed that Rice was failing. The two men took shelter behind an iceberg. Rice claimed that he was just tired, and even joked feebly with Fredericks, but then his mind began to wander. Fredericks watched in desperation as Rice was taken up with recollections of home and food, and then slowly drifted into unconsciousness.

Jim Lotz, Writer: It's astonishing in this extreme situation, the affection of these tough western soldiers. And Fredericks does all he can to sustain him. He even took his parka off and wrapped it around Rice.

Narrator: George Rice died in Fredericks' arms that evening. "I stooped and kissed the cheek of my dead companion," Fredericks recalled, "and left him there for the wild winds of the Arctic to sweep over."

By now, Fredericks himself was half-frozen. For seven hours, he dragged himself across the ice field before finally reaching their sleeping bag. Then, after just a few hours' rest, rather than returning to safety at Camp Clay, he chose to walk back to Rice's unburied body.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: It was an amazing, kind of an amazing gesture. And he hacked some ice to create a makeshift grave for Rice. Clearly, Rice had earned more than respect, almost adulation for all his efforts. And then Fredericks brought back all of Rice's unused food to the group. It's as if he had been inspired by his friend's unselfishness. It's quite moving.

Narrator: "Rice," Brainard wrote, "was as brave and noble as any man the world has ever known."

As death began to stalk Camp Clay, Henrietta gave up on the men in Washington. Ever since being rebuffed by the Secretaries of Navy and War, she had urged the mounting of another rescue mission. But her pleas had yielded nothing but cold, evasive replies. No one would take responsibility.

David Shedd, Greely Descendant: It would almost be as if we sent people out into space, lost track of them, and then argued about whether we could afford to go look for them.

Narrator: If Henrietta was ever going to see her husband again, she would have to turn the will of Congress, the Army, and the President. Henrietta took her cause to the press. She didn't have many connections, but she worked them tirelessly, urging one cousin to pester the Chicago Tribune, another the Atlanta Constitution, while others did the same in Denver, New Orleans, Philadelphia and elsewhere.

Michael Robinson, Historian: The rising clamor among the popular press for the government to do something about it, and the fingers that were being pointed at the Secretary of War and the Army were fueling public interest in it.

Jim Lotz, Writer: It became very obvious that the army had screwed up to put it mildly and the media started to ask about these things. Then the pressure became stronger and stronger and stronger until they just had to do, the military had to do something.

Narrator: The Greely expedition had caused barely a ripple when it left three years earlier; but now the public was clamoring for its rescue. On the 23rd of April 1884, the first of three rescue ships sailed out of New York, cheered on by crowds lining the new Brooklyn Bridge.

Adolphus W. Greely (Tim Hopper): "June 6th, 1884. Private Henry will be shot today. This order is imperative and absolutely necessary for any chance of life. Lieutenant A.W. Greely."

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: Henry was a big guy, he'd begged to get on Greely's expedition... but he had a very checkered history. Henry just stole food and to hell with it. And it got to the point where Greely warned him, "listen we can't have you stealing food." But he was the strongest man. He figured he could handle himself. They were too weak to do anything about it.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: It was absolutely necessary that that happen because he would in fact have stolen more and more food as the men became weaker and weaker and they would have all died.

Narrator: The fact was, they were all dying. Death had come in waves — five in the second week of April, four in the middle of May. By the beginning of June only 14 men remained, eating moss, candle wax, bird droppings. The survivors came to recognize the mental breakdown that presaged death. "At the first wanderings," Greely wrote, "we looked at each other, conscious that still another was about to pass away." The encampment was littered with unburied bodies. Greely himself was having difficulty thinking and speaking clearly, and his heart was weakening. When he gave the order to shoot Henry it caused barely a murmur of protest. The 10 remaining survivors confided wills, testaments, and farewells to their journals. David Brainard wanted the world to know about the commander he had once despised.

David Brainard (Rich Porfido): "I had rather be laid out by his side on Cemetery Ridge, than go back without him, so great is the respect, admiration and affection that I have formed towards him this winter."

Adolphus W. Greely (Tim Hopper): "Darling Retta, We but await the grave. Do not wear mourning for me. How happy we were four years ago at the Aberdeen Hotel...."

Narrator: June 20th was the sixth anniversary of Greely's wedding. He marked the occasion by putting his wedding ring back on, telling one of the men, "I have a feeling it may bring us good fortune." But that night a bitter storm collapsed the tent the seven survivors had occupied when the shelter flooded. For 24 hours they drifted in and out of consciousness, so that no one was quite sure whether they had really heard a ship's whistle the next evening.

When members of the rescue party reached Camp Clay, they came upon a scene of horror. "Close to the opening lay what was apparently a dead man," one recalled. "On the opposite side was a poor fellow without hands or feet, with a spoon tied to the stump of his right arm. Two others were pouring some liquid from a rubber bottle into a tin can. Directly opposite, on his hands and knees, was a dark man in a tattered dressing-gown, with a long matted beard, and brilliant, staring eyes. 'Who are you?' we asked. 'Greely, is this you?'"

The expedition's scientific records were retrieved and despite Greely's strenuous objections the bodies on Cemetery Ridge exhumed. The ship's doctor reported that none of the survivors would have lasted another 48 hours. Ellison was the last casualty: he died on board after a series of amputations. Of the original 25 men, only six would return home.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: The survivors must have been in shock on that entire trip home. One afternoon Brainard was standing near the galley and one of the crew asked him, what he was doing. And he was saying, I was just watching them throwing out the garbage, and in the last hour he saw enough food thrown out to have saved the lives of their 19 dead.

Narrator: On arriving at St. John's, Greely wired Washington: "For the first time in three centuries," Greely proclaimed, "England yields the honor of the farthest north. The two years' station duties, observations, explorations, and the retreat to Cape Sabine were accomplished without loss of life, disease, serious accident or even frostbite." Adolphus Greely wanted the world to know that he had fulfilled his two-year mission. As for the horrors of the last winter, someone else would have to answer for that. And by this time talk of those horrors had begun to circulate.

Philip Cronenwett, Historian: It was very clear that some of the bodies had had flesh stripped off, and that it, the flesh had been cut off with a knife. Clearly humans had taken that flesh off.

Jim Lotz, Writer: There was an effort to cover up and to conceal the cannibalism but there's no way you can make any information system airtight.

Narrator: "The facts hitherto concealed," the New York Times declared, "will make the record of the Greely colony the most dreadful and repulsive chapter in the long annals of Arctic exploration."

Jim Lotz, Writer: Oh, they were all over it. This was the thing that overshadowed the whole, the achievement of the expedition.

Narrator: All of the survivors were implicated, but Greely in particular was portrayed as a monster. He couldn't deny that cannibalism had taken place, but he vehemently denied having known about it. It did no good. He found the scandal more painful than anything he had endured at Camp Clay. It would follow him for the rest of his life.

Jerry Kobalenko, Writer: The thing about the Greely expedition is that it became a morality play. It started as a scientific expedition with a bunch of people squabbling; it became a morality play.

Narrator: The Army seemed to hold a grudge against the survivors for having tarnished its reputation. The promotions Greely had made in the field weren't honored, and the men's pay was held up for years. But Greely remained devoted to the survivors, and to the dependents of the men who had perished. Greely spent the years after the expedition collecting and publishing their scientific data with a devotion befitting a solemn memorial. But the scandal that haunted Greely had also tainted his scientific achievements. For more than a century his records gathered dust, until once again the Arctic captured the world's attention.

Michael Robinson, Historian: We are now using Greely's data to understand how global warming happens, to understand how the climate has changed over the last hundred years. The irony is that the data is of interest today but not because it offers the key to an understanding of nature, but because it offers a key to how human beings have changed nature.

Narrator: Adolphus Greely died in 1935, at the age of 91. He was a good soldier to the last — he never complained publicly of his expedition's abandonment. He is buried at Arlington Cemetery, next to Henrietta. He had never again left the woman who, almost alone, had kept faith. Nearby is the grave of David Brainard — the two men forever as close as they were during the long dark winter at Camp Clay.