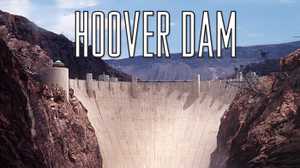

Narrator: It has been called an American pyramid — a sixty-story colossus of concrete, built in the middle of a desert every bit as brutal as in ancient Egypt.

T. H. Watkins, Author/Historian: Hoover Dam changed the history of the West. This is the biggest damned dam that anybody had ever seen.

Donald Wolf, Author/Engineer: There were many people who said it was physically impossible to build Hoover Dam, engineers who said that.

Narrator: In the 1930s, thousands of unemployed men came to this desolate canyon and, for a few dollars a day, risked their lives to build Hoover Dam. One hundred twelve died on the job, while extreme heat and working conditions brought illness or injury to uncounted others.

Ila Clements-Davey, Worker’s Daughter: Everybody that came here was desperate or they left before they even got a job. It was…about the worst nightmare you could think of working in.

Narrator: Their challenge was to harness the country’s wildest river, the mighty Colorado, to bring water, power and people to the Southwest. Now, in a more environmentally-conscious age, many wish Hoover Dam had never been built. Yet it stands as a monument to the ingenuity, and the sheer human will, that forever changed the face of America.

W.A. Davis, Photographer: I loved that old river. It was beautiful. I’d swam the river, I’d boated the river, I’d taken people up the river on trips… I felt bad to see it tamed, to tell you the truth.

Narrator: The Colorado was a river unlike any other— dark and red with mud and silt from carving out the planet’s most magnificent canyons. It ran wild until 1901, when Western farmers set out to tame it. Their plan was to water the desert. Developers dug a canal system that brought the River into lower California, and turned parched soil into a vast agricultural paradise they called the Imperial Valley. For four bountiful years, farmers thought they were living a miracle. Then, without warning, the river struck back. In 1905 the Colorado tore open the canal and flooded the valley, creating an inland sea across 150 square miles. Over the next two decades, floods would wipe out thousands of farmers. Millions of dollars were lost.

Blaine Hamann, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: The river was an enemy, and only in short periods of time could you look at it as a useful river. Most of the time it was something that would kill you or ruin your farm.

Guy Louis Rocha, Nevada State Archivist: The Colorado River was out of control and everybody says, “We have no dams, we need a dam,” and people started seriously looking at where to put a dam after 1907, up and down the river.

Narrator: The 1,400-mile Colorado became the obsession of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the agency charged with finding ways to irrigate the arid West. In 1920, the Bureau embarked on an ambitious plan to dam the Colorado and distribute its water hundreds of miles in every direction. It was called the Boulder Canyon Project. Survey crews were sent down the treacherous river to look for the best place to build what would be the largest dam in America.

Blaine Hamann, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: One of the slogans at the time for the river was that it was “too thick to drink and too thin to plow.”

Narrator: The battle to conquer the Colorado soon turned deadly. On December 20th, 1922, a surveyor, J.G. Tierney, fell off a boat and drowned. Tierney was the first man to die working on the project.

Man (archival): This is the site in the Black Canyon, picked first by Homer Hamlin in nineteen hundred and seventeen. The dam will be about…

Narrator: After four years of surveys and tests, Bureau engineers chose Black Canyon, on the Arizona-Nevada border, as the site for Boulder Dam. But the $165 million price tag for a Western water system made the Eastern establishment nervous.

Guy Louis Rocha, Nevada State Archivist: The thing is, this was not a done deal, politically. It had to be sold in Washington, DC, it had to be sold to Congress. Politics had been dominated in the East. To talk about flood control in the West was to allow the West to get up and ask for more than they had been asking for.

Narrator: An uncommon sight began to spring up in the rugged canyon — politicians running the river in three-piece suits. One of them was Herbert Hoover, the Secretary of Commerce, and a former engineer. In 1922 Hoover negotiated an agreement among the seven western states that shared rights to the water to be captured by the proposed Dam. With the contract in hand, the project cleared its first big political hurdle. But convincing Congress to send millions out West for the most expensive public project ever seemed impossible… until the Bureau came up with the way to pay for it—electricity. By selling the dam’s hydroelectric power, the Bureau would fuel the growth of farms and cities across the emerging Southwest. Los Angeles, its ever-sprawling metropolis, would be by far the single biggest customer.

W.P. Whitsett, Chairman, Metropolitan Water District (archival): We here in Southern California, we’re building a great empire. If we are to survive and to grow, we must have the water that will enable us to maintain our mastery over the desert.

Narrator: In 1929, after twelve years of intense lobbying, Congress finally authorized the funds. It was welcome news for a nation fallen on hard times.

W.A. Davis, Photographer: We was in a depression, flat on its back, belly up. The press made an announcement that the government was going to build the largest dam in the world, so I went over to a car lot and bought a ’26 Essex car for $75 dollars, got into it and took off for Las Vegas.

Narrator: Las Vegas, of all places. Thirty miles from Black Canyon, it was the only town anywhere near the dam site. Suddenly, thousands of jobless Americans were heading for a down-on-its-luck railroad stop in the middle of nowhere.

Guy Louis Rocha, Nevada State Archivist: They were desperate for work. And they were coming from anywhere and everywhere. Las Vegas was the mecca. Las Vegas was an opportunity, Las Vegas was a place to bring one’s family and maybe have a livelihood.

W.A. Davis, Photographer: Everybody took for granted that there was a job, might be a job available when they got there. But the government didn’t warn the people that building of the dam wouldn’t start for almost a year, there wouldn’t be any jobs. And to come out and set up camp out in the desert was a pretty rough deal.

Guy Louis Rocha, Nevada State Archivist: People were living hand to mouth, living at the Union Pacific Railroad Station on the grass, courthouse grass. The town was overwhelmed.

Narrator: Others moved farther out toward Black Canyon, to a deadly, desert place they called Ragtown.

Ila Clements-Davey, Worker’s Daughter: There was just nothing. There was no facilities. Nothing. It was just, you dumped the family out in the desert and that’s it. And down where we were it was like 130 degrees. And my mother and father didn’t even have a tent. And my grandmother was so afraid, she didn’t think that we’d live through it. And she says, “I don’t think I’ll ever see you again. Won’t you please reconsider and come.” And Mother said, “No, I’ve got to be with my husband.”

Guy Louis Rocha, Nevada State Archivist: I suspect most people came from places where things were green. There was nothing green around here. Everything was baked, and hot, and brown. This was their future. As scary as it looked, as fearful as this terrain was, this was their future and they knew it.

Narrator: By the summer of 1930, the government had not yet hired a contractor to build the Dam. But the Bureau did begin laying rail and phone lines from Las Vegas out to Black Canyon. It hardly solved the unemployment problem, but it was a start. On September 17th, Ray Lyman Wilbur, Secretary of the Interior for Herbert Hoover, who was now President, came out to drive a silver railroad spike and mark the project’s official beginning. Most Americans blamed Hoover for doing nothing about the Depression, and he badly needed some good press. Wilbur, wearing a wool suit in 100-degree heat, had his work cut out for him.

W.A. Davis, Photographer: Secretary Wilbur drove the spike, he missed it about three or four times. And of course there was a lot of miners in the background to tell him what a poor punk he was. I think that he was quite embarrassed.

Narrator: But Wilbur’s most lasting blow was struck in his closing remarks.

Ray Lyman Wilbur, Secretary of the Interior (archival): I have the honor and privilege of giving a name to this new structure. In Black Canyon, under the Boulder Canyon Project Act, it shall be called the Hoover Dam.

W.A. Davis, Photographer: That really went over like lead balloon. Boy, you should have heard them. They hooted and they hollered and called him a sonofabitch and everything else they could think of.

Narrator: The Dam’s new name would be a subject of dispute for the next seventeen years. Builders from around the country came to study Black Canyon. But whoever did the job would have to come up with a $5 million performance bond, a risk far beyond the means of any one construction company. In the West, a group of independent contractors formed a partnership they called Six Companies. Prominent among them were Henry Kaiser, an ambitious young road builder from Oakland, California, and his mentor, Warren A. Bechtel, a powerful old-line San Francisco contractor.

T. H. Watkins, Author/Historian: The compelling temptation to build this thing drove them. They just wanted it. There was money to be made. But there was something beyond that. This was the biggest project that anybody had ever thought of.

Narrator: The men of Six Companies would be gambling their money and their reputations. But they had an ace in the hole—the one man they believed could pull it off—an engineer named Frank Crowe.

Donald Wolf, Author/Engineer: He was a commander, a field commander. Everybody knew he was good at his work. Everybody knew he was firm and fair and consistent. What he loved best was gettin’ his boots muddy down in the river bottoms building dams.

Narrator: Frank Crowe had once been the Bureau of Reclamation’s Number One dam builder. But when the Bureau decided to hire outside contractors for their most ambitious dam ever, Crowe quit his government job and signed on with the men who planned to build it.

Al M. Rocca, Crowe Biographer: He was wild to build that dam. This was his dream. And he wanted to be known as the greatest dam builder who ever lived in America. When Frank Crowe appeared on the scene, he was unmistakable, let’s put it that way, at, uh, six foot-three to six foot-four in height. A commanding presence that made a lot of men feel like, wow, he’s the boss.

Narrator: But even a man like Frank Crowe was unprepared for a place like Black Canyon.

Blaine Hamann, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: It looks like it could be some place on the moon. Nothing but hard solid rock and deep canyon. Everything was just harsh, harsh, harsh.

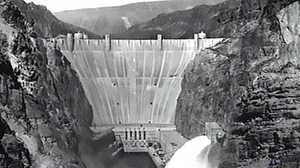

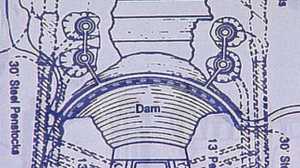

Narrator: A Six Companies engineer admitted they “were all scared stiff.” The government’s plans called for a massive concrete wedge over 700 feet high, twice as tall as the Statue of Liberty, and two football fields wide at the bottom. Workers would have to build two power plants at the base, and dig four long tunnels through hard canyon rock to divert the river around the work site. They would need to pour 4 1/2 million cubic yards of concrete— enough for a two lane road from Los Angeles to Boston— and build a city in the desert, virtually overnight, to house 5,000 workers and their families.

On March 4th 1931, Frank Crowe submitted Six Companies’ winning bid. In Las Vegas, the waiting was finally over.

Maxine Riepen, Secretary, Employment Office: There were hordes of men there, desperate men.

Narrator: Maxine Riepen was fresh out of Las Vegas High School when she got a job at the dam’s employment office. Her boss, Leonard Blood, reported that in its first three weeks his office had received 12,000 letters of inquiry.

Maxine Riepen, Secretary, Employment Office: A man came in one time. Mr. Blood took a look at him and says, “You’re too old!” He had a gruff voice and, uh, the man had white hair. The man looked so dejected. And he went out, and a couple of weeks later, here comes this man back in, and he’s dyed his hair, he’s changed his name and he got in line and Mr. Blood didn’t even recognize him. I did because I was sitting there watching him all the time. And that time he got a job.

Tommy Nelson, Worker: I was playing with a dance band in Grand Junction, Colorado, practically starving to death, y’know. People were so poor they couldn’t afford to dance. So my dad says if you come out I can getcha a job. Well, little did I know, I’ve never done anything but blow that horn. I didn’t know what to expect.

Blaine Hamann, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: Trying to imagine what it must have been to go down there and start work on that site you know, leaves me with a feeling like, you know, what if you were the first one to dive down there and you picked up the shovel, looked around you and said, “I guess I’ll start digging right here.”

Narrator: In the beginning there were no roads. Down at the bottom, there was no dry place to stand.

Al M. Rocca, Crowe Biographer: There’s no access there. You’ve got an amphibious assault of these troops coming down on barges, cutting out landings like a beach landing in a World War II amphibious assault.

Narrator: Crowe sent miners down the river to start the first and most dangerous phase of construction: the four diversion tunnels, two on each side of the river. Work crews would have to drill and blast three-quarters of a mile through the canyon walls to open the holes that would carry the river around the work site. 56 feet in diameter, they would then be lined with three feet of concrete.

Blaine Hamann, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: Those diversion tunnels were unique. To get them lined up, the job of drilling and shootin’ with dynamite, y’know, removing the rock. It was logistically one of the toughest things they did on the dam.

Narrator: Six Companies also had to contend with a rigid government deadline — two and a half years to divert the river or face steep fines for every day they ran late. The volatile Colorado constantly threatened the job. In a flash, seasonal floods could wash away any plans for finishing on time. An almost comic contraption turned out to be Frank Crowe’s best weapon against the tunnel deadline. The steel and wood beast, called a drilling jumbo, carried three tiers of drills on a ten-ton truck. The rig was backed up to the face of the wall, and the thirty drills bored holes into the rock to plant dynamite. The jumbo could then be pulled away for blasting, and the whole operation moved to the next drilling area.

W.A. Davis, Photographer: That was a pretty clever idea. Because before, they’d have to put up staging. Then the staging would have to be taken down when they blew the face. And then they’d have to replace it. It was a big time saver.

Blaine Hamann, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: 10 million cubic yards of rock had to be moved. Drag lines, electric power shovels, trucks, men, dynamite, drills, noise, thunder, dust.

Al M. Rocca, Crowe Biographer: There were always cave-ins, there were always loose and sharp rocks falling about. You had men stumbling in areas that were not correctly lighted. Getting in each other’s way. You had men hurrying the job up considerably because they needed to move on because of the pressures they were getting from their foremen or the assistant superintendent.

Narrator: In the rush to make their deadline, Six Companies sacrificed safety for speed. Frank Crowe prowled the dam site day and night. To his men, he was both God and the Devil — fair, but intensely demanding. They gave him the nickname “Hurry Up” Crowe.

Tommy Nelson, Worker: The Six Companies foremen, they were on me all the time. Keep the trucks movin’, everybody movin’. I was the flagman, flaggin’ dump trucks. And lo and behold I took a look up, and saw a high scaler way up high on the Nevada side comin’ down, and he fell very close to where I was standing. So I take a quick look, thinking that there’s no trucks coming, and make a mad dash over to this guy. There’s nothin’ I can do for him. Along comes a hard-boiled superintendent, and I told him there’s a man killed over there. And he said to me, in no uncertain terms, “What are you going to do with all these blankety-blank trucks? Eat 'em? Get the trucks moving! He can’t hurt anybody.”

Narrator: Crowe’s most experienced workers had followed him faithfully from dam to dam, but many more had simply come for a job, any job, and knew little or nothing about this kind of work.

Tommy Nelson, Worker: My first shift, was in one of the big diversion tunnels. The foreman come by and he’d say “Nelson — go down the tunnel get a jackhammer, bring it up here and break up this rock.” I hated to admit to him that I was so dumb. I didn’t even know what a jackhammer was!

W.A. Davis, Photographer: A lot of these young men, they wasn’t used to this heavy work, the environment. The heat was terrific, the noise was unbearable.

Tommy Nelson, Worker: I’ll tell ya I was pretty discouraged about the first night I put in. They put me on the graveyard shift and I said to myself, “I don’t know whether I can take this or not, but I’ll give it my all.”

Narrator: That first summer the Six Companies payroll reached 1,400. The work never stopped — three shifts a day, every day.

W.A. Davis, Photographer: You had to work seven days a week. You couldn’t work five and a half days, which most people did. And if you didn’t like it, why they’d can you.

Tommy Nelson, Worker: Two days off a year — optional, without pay. The Fourth of July and Christmas. The contractor never had it so good, because he had the pick of the nation’s best labor at the price he wanted to pay him.

Narrator: It was a brutal job under the best of circumstances. But the summer of 1931 was one of the hottest on record. The men worked in blistering heat without shade and adequate drinking water. Workers collapsed from the heat, some with body temperatures as high as 112 degrees. The lucky ones were packed in tubs of ice water and survived. By August, heat and dehydration had claimed fourteen lives.

Tommy Nelson, Worker: Hot! Temperatures, 135, 140 degrees, in those diversion tunnels. The carbon monoxide was so thick a string of lights along the canyon wall looked like somebody striking matches. You’d come out of there with a headache that wouldn’t quit.

Narrator: Nevada law prohibited gasoline powered trucks in the tunnels. But Six Companies, claiming the job was under federal jurisdiction, used them anyway. Carbon monoxide and dust choked the tunnels and silently poisoned the men inside.

Guy Louis Rocha, Nevada State Archivist: Carbon monoxide was knocking these men down, making them very, very ill. When they were taken to the hospital, the doctors would say, “It’s pneumonia!” They would not say, “It’s carbon monoxide poisoning and Six Companies is responsible.” They were saying, “It’s pneumonia — we’re not responsible.”

Narrator: Temperatures and tempers reached the kindling point on August 7th, 1931, when Six Companies re-assigned a number of workers to lower paying jobs. Organizers from the radical labor union, the Industrial Workers of the World, pressed for action. Within hours, the entire work force went out on strike. The canyon fell strangely silent.

Guy Louis Rocha, Nevada State Archivist: Even the more loyal workers not interested in union activities, not necessarily even interested in striking, were at the point where they were saying, “We’ve gotta do something.” They wanted clear water, good water, cold water, they wanted the electrical lines that were near puddles where people were being electrocuted, to be moved, they wanted the dynamite put into safety places. The dam was moving so quickly, the Six Companies were not making the necessary provisions for safety. As much as they were saying they were, they weren’t. And the workers knew that.

Narrator: Frank Crowe took the strike as a personal betrayal. His bosses at Six Companies stood firm. “The workers will have to work under our conditions,” they said, “or not at all.” They rejected every worker demand and banished suspected union members. After six days, the strike collapsed. Security was beefed up and a control gate installed, while Leonard Blood and his staff at the employment office began re-assembling the work force.

Maxine Riepen, Secretary, Employment Office: One day, Mr. Blood was sick… well, hung-over is a better word, but anyway. He came by and says, “Maxine, you’re going to have to do the hiring today, I’m going home.” So they called in and wanted 90 laborers. They said, “Can you hire 90 laborers?” And I said, “Sure!” You have a lot of confidence when you’re young. And I thought, here’s my chance to get all these young boys that haven’t had a chance to go to work, to put their names up. So I did. And when they went out, the foremen were making a joke out of it, saying that when I did the hiring, it looked like a college campus, but when Mr. Blood did it, it looked like an old people’s home.

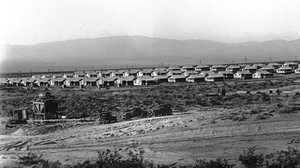

Narrator: As the hellish year of 1931 turned to 1932, tensions eased when Six Companies finally moved workers and their families out of Ragtown and into Boulder City. It was a modern, model community, free of the liquor and gambling that was Las Vegas’ stock-in-trade. Single men moved into large dormitories, while row upon row of one, two and three room family cottages went up in a fury of sawdust and sand. The landscape changed so rapidly that it was common for a man to come home after his shift and walk into the wrong house.

Ila Clements-Davey, Worker’s Daughter: Oh, it not only grew daily, it grew nightly. I couldn’t remember sleeping that hammers weren’t going and stuff like that. And how the people on the swing shift slept, I’ll never know.

W.A. Davis, Photographer: They built them rabbit hutches and called them houses. Crude as could be. They cost about five, six hundred dollars apiece and they rented them from fifteen dollars up, depending on how many rooms you had.

Narrator: But as one resident put it— “to us, it was beautiful.” In the unsettled world of the Depression, Boulder City offered families a security they hadn’t known in years.

Ila Clements-Davey, Worker’s Daughter: They built communities very fast. In the neighborhood, I knew every single neighbor loved me. I knew that. And I could go to any home, knock on it any day. I was never… There wasn’t such a thing as fear of a child being out, you know, and something happening to them.

Narrator: It was a fenced and gated world unto itself.

Ila Clements-Davey, Worker’s Daughter: Boulder City was run really very much like an army camp with great restrictions to what could go on and what couldn’t go on, and a law enforcement that saw to it that these things were carried out.

Guy Louis Rocha, Nevada State Archivist: Boulder City had elements of both the model town and the police state. There was a certain comfort level you paid, but you gave up freedom for the comfort level.

Narrator: A shiny new mess hall served 6,000 meals a day. Every week twelve tons of fruit and vegetables were shipped in, along with five tons of meat, and two-and-a-half tons of eggs. For a $1.15 a day a man got three squares and all he could eat.

Tommy Nelson, Worker: This box lunch, they’d carry that down. And some of those guys could chunk ten sandwiches in there, two pieces of pie, and maybe a couple of oranges.

Narrator: For Herbert Hoover, the Depression had taken its toll. He lost the 1932 election to Franklin Roosevelt by a landslide. A week later he stopped off at the dam site on his way from California to Washington. He stayed only briefly, and left just hours before his beloved project faced its most crucial test. On the morning of November 13th, the nation’s media converged on Black Canyon to witness the historic attempt to re-route the Colorado.

Tommy Nelson, Worker: At 11:30 in the morning, a blast was put off down there, near the entry, in one of the big diversion tunnels. That was what put the show on the road.

Narrator: Now they had to force the raging Colorado to change direction. Throughout the day, workers furiously dumped tons of rock into the river’s path, trying to build a barrier high enough and strong enough to push it back into the tunnels. By dawn, the battle was won. Man had moved the mighty Colorado from the bed it had known for 12 million years. For Frank Crowe, it was a personal triumph — he had beaten the river, and his deadline, by eleven months.

Guy Louis Rocha, Nevada State Archivist: Once the water was being bypassed, over that site, people came to worship in a way. People couldn’t help but make the pilgrimage to this wonderful technological achievement. Hell, the country’s out of control, the economy’s out of control, but we’re controlling the Colorado River.

Narrator: “The vast chasm seemed a slit through earth and time alike,” wrote author Frank Waters. “The rank smell of Mesozoic ooze and primeval muck filled the air. Down below grunted and growled prehistoric monsters — great brute dinosaurs, steam shovels and cranes feeding on the muck, a ton at a gulp. And all this incessant monstrous activity took place as if in a world taking shape before the dawn of man.”

Ila Clements-Davey, Worker’s Daughter: The men were just swarming over the whole place, they just looked like a hill of ants they really did. It was just fantastic to watch all that going on. It was a monumental task.

Narrator: Of all the jobs on the dam, none was more dramatic and dangerous than that of the high scalers—men swinging from ropes 800 feet up, armed with dynamite and jackhammers, to blast and clean the canyon walls, and prepare them to take the dam’s concrete. Their exploits became legend — real honest-to-goodness cliffhangers.

Ila Clements-Davey, Worker’s Daughter: It was like a movie of Tarzan, you know. You’d hear the blast and then see those guys fling themselves down there and start ripping the rocks off and there were people above them and people below them.

Maxine Riepen, Secretary, Employment Office: I remember this big, strong-looking man fell. And, uh, he yelled as he fell and this high-scaler below him swung out and caught him as he was falling and saved his life. Oh, he got write-ups and was quite a hero after that. Others… there were two or three that fell to their death. Maybe even more.

Narrator: By 1933, Six Companies was two years ahead of schedule and reported a profit of $3 million. They had pretty much had their way with the project, until the New Deal’s own force of nature, Harold Ickes, took over as Secretary of the Interior.

T. H. Watkins, Author/Historian: One of the first things he did was to rename it Boulder Dam. Now this stemmed not merely from the— his stated position that it was not seemly to name a dam after a sitting president, but because he really did not like Hoover at all. He also was very, very irritated with the Six Companies in the way that blacks were discriminated against on the job, put a stop to discrimination in hiring. He made it a point that blacks should be considered as well as whites.

Narrator: In the first year of construction, not a single black worker had been hired. When Ickes took office there were only twenty four African Americans in a 4,000 man work force. Ickes pressure led to more minority hiring, but no blacks were allowed to live in Boulder City.

Ila Clements-Davey, Worker’s Daughter: This was a closed community. Negroes were not, there was no way a negro could get in here. No way anyone with a colored skin could get in here.

Narrator: Black workers were transported to the work site on separate buses and drank from separate water buckets. Hiring may have opened up, but the dam remained a segregated workplace. The major event in every worker’s life was payday. Twice a month, on the tenth and twenty-fifth, they cashed their paychecks, burst out of the moral confines of Boulder City and headed down the highway to Las Vegas — to the gambling halls, bars, and brothels of its infamous Block Sixteen. At sun up, the men would stagger back to Boulder City, and for the next fifteen days, Las Vegas went back to bed.

On June 6th, 1933, after two years of preparation, workers finally poured the first bucket of concrete that would build the dam’s famous face. Frank Crowe now had 5,000 men working in a deep and narrow canyon. His main task, he said, was to keep them from accidentally killing each other. Sixty-five had already lost their lives. To transport the concrete, Crowe designed an elaborate network of aerial cableways that carried material to almost anywhere on the dam site. Before long the cables were delivering a concrete bucket every 78 seconds.

Blaine Hamann, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: Doggone, pretty tricky job. Twenty-ton bucket roaring down the canyon just as fast as they could get it there. And the fellow that was running the crane couldn’t even see where that bucket was going. He was steering that thing by Braille, boy, I’ll tell ya.

Narrator: The buckets poured concrete into blocks five feet deep, that were stacked one on top of another in interlocking columns to form the dam’s structure. If the builders had tried to pour one continuous concrete wall, it would have taken 125 years to cool. Though legend claims otherwise, no workers were buried in the dam’s concrete. While the arch was going up, workers were constructing the four intake towers on the cliffs behind. Thirty-three stories high, they would deliver water from the reservoir to the power plants under construction below.

Blaine Hamann, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: There were things happening every second of every day down there. All the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle that had to be in place for this industrial construction to go on is just simply amazing.

Narrator: Frank Crowe’s workers were pouring more concrete in less time than anyone thought possible. He had succeeded in turning a ragtag army of unemployed into America’s most celebrated work force. On February 6th, 1935, the last bucket of concrete topped off the dam at 726 1/2 feet. That week, a steel bulkhead gate closed off the last diversion tunnel. The Colorado slowly began to pool behind the dam. It would form Lake Mead — 115 miles long, 500 feet deep.

Ila Clements-Davey, Worker’s Daughter: We got into what I call now the little puddle that was the lake at that time, and we went up to the back part of the dam and this great big structure this, oh my God… big hunk of concrete, corkin’ up the Colorado River. And the intake towers sitting on the cliffs, way up above us. Now when you go over the dam it looks like the intake towers are right in the middle of the lake, you know, and, and the dam, you only see a small portion of it. You can’t get the feeling of the immensity of the dam, and it looks a lot bigger from that side then it does from the face side. It really does.

Richard Guy Wilson, Architectural Historian: Dramatic, it looks like the hands of man holding back the canyon walls.

Narrator: From the beginning, the dam’s visual design had been given extraordinary attention.

Richard Guy Wilson, Architectural Historian: The Bureau of Reclamation realized that this was an epic-making construction. And the consequence is that they called in Gordon Kaufmann. And he took the banal details of the engineers that were in the original specifications and he turned it into one of the great modern landmarks of the 1930s.

Narrator: Architect Gordon Kaufmann, gave the dam its futuristic style. He transformed ordinary concrete surfaces into modern art deco designs. The electrical transformers took on the look of a 1930s Buck Rogers space movie. The intake towers rose out of the lake like rockets to the moon. And the streamlined spillways gave the huge mass a constant sense of motion. Inside the powerhouses hum the engines of the American southwest — 17 turbines generating more than 2 billion watts of electricity — enough to supply 1.3 million people. The power plant’s terrazzo floors recall the Native American heritage of the land.

Richard Guy Wilson, Architectural Historian: They are modeled on Indian designs, Navajo pottery, symbols that look remarkably like the modern machine, the turbine, the gears that are all in motion. It’s a perfect example of reaching to the past and abstracting from that, for the future. It’s like a chapel in a sense. It’s like the chapel of the machine age.

Narrator: On September 30th, 1935, a crowd of 20,000 swarmed over what was being called the eighth wonder of the world. President Roosevelt came to dedicate the Dam—two years ahead of schedule.

Franklin Roosevelt (archival): I have the right once more to congratulate you who have built Boulder Dam, and on behalf of the nation, to say to you: “Well done.”

Narrator: In one final flourish, the designers inlaid a celestial map to mark the exact position of the stars on the day of the President’s dedication.

Blaine Hamann, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: This was built in a time when it was the first big one. And so many engineering feats afterwards have always kind of had a kind of connection to the building of Hoover Dam. In a sense of ah… this is where we learned how to do it.

T. H. Watkins, Author/Historian: It was a very, very important thing as symbol of what they felt could be done in a world that had gone all to hell.

Narrator: On December 20th, 1935, a worker named Patrick Tierney fell from an intake tower and drowned. He would be the last man to die on the project, 13 years to the day after the first man died—J.G. Tierney, his father.

W.A. Davis, Photographer: When I was lookin’ at the dam, I thought of the young men that had given up their lives to build the damned thing. That’s what I thought of when I was looking at the dam.

Narrator: At the bottom of Lake Mead, 500 feet down, lie the remains of places like Ragtown. The ancient river valley is long gone. Hoover Dam heralded the beginning of the modern industrial west. Its electricity spurred unprecedented growth. Its flood control and irrigation created some of America’s biggest farms and allowed them to flourish in the desert. The men of Six Companies went on to become some of the richest contractors in the world, and Frank Crowe took home a $350,000 bonus from the job. He would build four more dams, but Hoover Dam — the name officially given it by Congress in 1947 — stands as his crowning achievement.

Tommy Nelson, Worker: I should say I felt proud, 'cause I was a part of it. As to that structure down there, right to this day, I still feel like holding my hand over my heart when I go down there. 'Cause that dam was a part of me. It was a part of me, I can assure you of that.