NARRATOR: June, 1934. Explorer Richard Byrd lay dying at the bottom of the world. In his diary he wrote: "I see my whole life pass in review. I realize how I have failed to see that the simple, homely, unpretentious things of life are the most."

BOLLING BYRD CLARKE, daughter of Admiral Byrd: I think Dad was as well prepared as he could have been but no one could have been prepared for that kind of experience, being ah completely alone under the most difficult of circumstances.

NARRATOR: Huddled in a one room hut burrowed into the Antarctic ice, Byrd drifted in and out of delirium, but would not call for.

LISLE ROSE, Historian: His whole persona had been of the person out on the cutting edge of adventure and the frontier, who really didn't need any help. Dick Byrd did it alone. Dick Byrd was the great hero.

NARRATOR: Byrd was already a famous man. He had received three ticker tape parades as the first to fly to the North and the South Pole, and as one of the first to fly non-stop across the Atlantic. But his greatest achievement would be opening up the vast unknown continent of Antarctica to science and modern.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: He dared great things and the people who dare great things have many sides to them. He wanted to contribute to history and science, he wanted to make money, he wanted to become a hero. And which one won out depended on the circumstances.

NARRATOR: The heroic image that Byrd created would not survive intact. Like all great men, he was driven to succeed, and at some point, bound to fail. In April, 1926, Lt. Commander Richard Byrd set out from New York for Spitsbergen, Norway. His ship carried 52 men and an airplane. He hoped to be the first to fly to the North Pole.

LISLE ROSE, Historian: Dick Byrd had to be first in anything he did. Ah, I think he felt always that it wasn't worth doing unless he was the first person to do it. And this was in Dick Byrd's.

NARRATOR: Byrd was in a race against Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen, the first man to reach the South Pole in 1911. Already in Spitsbergen, Amundsen hoped to conquer the North Pole in a dirigible. When Byrd arrived, he was upset to find a Norwegian boat blocking the pier. He ordered his crew to construct a makeshift raft out of lifeboats.

BYRD Quote: I decided to take chance and get plane ashore somehow. We may be licked but don't want to be licked waiting around and doing."

RAIMOND GOERLER, Byrd Archives: So in this incredible risky maneuver in which one cake of ice ah, one particularly dangerous wave could have knocked his airplane, his tri-motor into the water. Byrd does the riskiest thing he's done in is entire career because he was bound and determined that this was his time to make it to the North Pole.

NARRATOR: When Byrd's plane reached the shore, the Norwegians were impressed. "To your health and success," said Amundsen. "I wish you brilliant accomplishments," replied Byrd. Byrd had long dreamt of being the first to the North Pole and, as a child, had been thrilled by the harrowing accounts of Arctic expeditions. Born in 1888, Richard Byrd came from one of the first families of Virginia. Once wealthy landowners, the Byrds were wiped out by the Civil War.

LISLE ROSE, Historian: Dick Byrd was born only 23 years after Appomattox, and the whole of the South was demoralized and felt very strongly that it had to prove itself again.

NARRATOR: Byrd's mother, Eleanor Bolling, was a Southern belle who encouraged her three sons, the proverbial Tom, Dick and Harry to rehabilitate the family name. His father, Richard Byrd, was a brilliant prosecutor but a solitary man and an alcoholic. He drove his boys hard, fostering in them a desire to succeed.

Dick was the most adventurous. "Danger was all that thrilled him," his mother said. In 1900, Byrd was invited to visit his godfather based in the Philippines, halfway around the world.

BOLLING BYRD CLARKE, daughter of Admiral Byrd: My father was extremely excited. His parents ah were not happy about the idea and I think his mother certainly didn't want him to go. It was much too dangerous for a small boy, the age of twelve to go alone.

NARRATOR: But Byrd did travel alone - and wrote letters home which were published in the local newspaper.

LISLE ROSE, Historian: He came back a celebrity and got the first taste of what adventuresome travel could do in the in the sense of awaking public awareness, and inciting public awe.

NARRATOR: At age 20, Byrd entered the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, in search of the recognition and adventure that he now craved. There, he pushed himself, but not in his studies.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: Byrd was small, and it made him interested in athletics and in conditioning. And he tried to become a great athlete or a good athlete at any rate, and in fact all his life was very proud of his physique.

NARRATOR: A fierce competitor, Byrd broke his foot playing football, then broke it again in gymnastics. After Annapolis, he fell down a hatch breaking his foot a third time. Because of his injuries, his career stalled, and he reluctantly retired from the Navy.

BYRD Quote: Career ended," he wrote, "trained for a seafaring profession; tempermentally disinclined for business. A fizzle."

NARRATOR: By this time, Byrd had married his childhood sweetheart, Marie Ames. From a prominent Boston family, she was attractive, totally supportive, and the love of his life.

Byrd's career was saved by World War I. Called back to active duty, he was eventually sent to Pensacola to train in a new field.

LISLE ROSE, Historian: He was one of the very early naval aviators. It was almost a foolhardy profession. Men were still learning how to build planes. And it was a very, very dangerous profession. You certainly were going to get hurt if you weren't going to get killed.

NARRATOR: Though he was afraid of flying, Byrd trained as a navigator and became naval aviator 608. He believed this new technology would change the world and help him realize his childhood dreams.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: Byrd reasoned that if he could fly to the North Pole and back in one day in relative comfort and accomplish what the old explorers had taken weeks or months to do that this would gain great publicity for aviation and incidentally for himself.

NARRATOR: After several frustrating attempts to fly to the Pole as part of a Navy effort, Byrd, now 38, set out to raise funds for his own Arctic expedition. Impressed by his vision, Ford, Rockefeller and others contributed. Newspaper rights netted him more money. Byrd's future was riding on the success of his flight from Spitsbergen to the Pole.

His first attempt was a failure. Just before take off, the landing skis collapsed. Byrd was in desperate need of help. It came from an unexpected source, Bernt Balchen, a member of Amundsen's team.

BESS BALCHEN URBAHN, former wife of Bernt Balchen: He was a flyer and a very good pilot and he also was a very handy person. He could do practically anything with his two hands.

RAIMOND GOERLER, Byrd Archives: Balchen helped to fashion special skis using the oars of the life boats. Balchan also advises Byrd that the best time to take off is late at night when the temperatures are cold, and the runway is iced over and is slicker.

NARRATOR: On May 9th, navigator Byrd, and pilot, Floyd Bennett, took off in the light of the Arctic night. What happened next is still a matter of debate. According to Byrd, they discovered an oil leak 100 miles short of the pole, but kept going. After eight and a half hours, Byrd scribbled a note to Bennett.

BYRD Quote: Radio that we have reached the pole, and are now returning with one motor with bad oil leak, but expect to be able to make Spitsbergen.

NARRATOR: Byrd returned much earlier than expected so the landing had to be restaged for the cameras. The flight was an American triumph. Byrd's logs were sent to the National Geographic Society, the sponsor of the expedition. The Society verified Byrd's claim - after minting a gold medal honoring him. Promoted to Commander by an act of Congress, Byrd said he had now entered the hero business.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: Byrd was extremely popular after his North Polar flight. He was an aviator and aviators were great heroes of the day. Byrd was an explorer, explorers were famous at the time. And besides that he was a handsome man, reputed to be a model person -- didn't drink, curse, go out with women. Ah, he was the kind of a man that women hoped their daughters would marry.

NARRATOR: After the celebrations, Byrd went home to Boston. By this time, he was the father of four young children.

BOLLING BYRD CLARKE, Daughter of Admiral Byrd: All of the children had a very difficult time with his absences. He was missed mightily and very much we looked forward to his return. The most fun we had was during the summertimes because he loved being with us. I just wanted to be with him all the time, to, ah, listen to his wonderful stories and, of course, it was such an adventure to be with him. He thought of all kinds of fun things to do.I adored him, and when he left, I really missed him.

NARRATOR: Soon after the North Pole flight, questions began to surface in the foreign press. Some reporters doubted whether he could have made the fifteen hundred mile journey to the pole and back in so short a time.

BESS BALCHEN URBAHN, former wife of Bernt Balchen: They said that they had seen a plane on the horizon and couldn't believe it because they didn't, hadn't expected the "Josephine Ford" to come back that quickly and ah so one of the ah reporters at the time, an aviation reporter for the Norwegian paper, "Aften Posten", questioned it right away.

NARRATOR: Others doubted Byrd in private. That summer, Bernt Balchen and the North Pole pilot, Floyd Bennett, took the Josephine Ford on a cross country promotional tour.

BESS BALCHEN URBAHN, former wife of Bernt Balchen: Bernt as always kept a very careful log and he realized that the plane wasn't as fast as it was supposed to be and he knew that something was wrong, that it couldn't have reached the North Pole and finally asked Bennett and Bennett definitely told Bernt Balchen that they had not reached it.

NARRATOR: Balchen kept this story to himself. Clearly, staying on Byrd's good side was a smart move for an ambitious young pilot. But doubts about the flight persist. Did Byrd fall short of the Pole, and if so, by how much and did he know it? The flight diary doesn't resolve the question Was Byrd's career as an explorer launched on a lie?

LISLE ROSE, Historian: Dick Byrd believed very strongly that life was a struggle. It wasn't something that you eased into and eased through. One became a hero through repeated search for transcendent challenges. And the supreme arena for surmounting them was Antarctica.

NARRATOR: One year after the North Pole flight, Byrd announced his next exploit. He planned to be the first man ever to fly over the South Pole. Operating out of a suite in the Hotel Biltmore, Byrd began organizing the most ambitious polar expedition ever.

NORMAN VAUGHAN, expedition member: I was studying at Harvard College one night and the door opened and in came the "Boston Transcript", the evening paper of the city, and there with banner headlines it said, "Byrd to the South Pole." I read it and at that moment I decided I wanted to go.

NARRATOR: Norman Vaughan was among the 10,000 who volunteered. Byrd wanted men with spirit - of mind and courage, and Vaughan fit the bill. Byrd was also counting on the donation of goods and services, and on raising over 500,000 dollars in cash.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: At that time Antarctic expeditions weren't financed by the government. They were solely financed by the people running the expeditions. So Byrd had to raise all the money for his expedition himself. And ah Byrd made himself a show business property.

Byrd signed up with a lecture bureau, arranged a book deal, sold syndication rights to "The New York Times," and the film rights to Paramount Pictures which assigned two cameraman to the expedition. Contributions came in from philanthropists, business leaders, and even school children. Edsel Ford donated an airplane.

In the midst of the preparations, Byrd was devastated when he learned of the sudden death of pilot, Floyd Bennett. Bennett had been Byrd's right hand man and closest friend. He would be hard to replace. Byrd soon named Bernt Balchen to head the aviation unit but postponed selecting a new pilot for the South Pole flight.

The Byrd Antarctic Expedition was ready to go in the fall of 1928. Four ships would carry 3 planes, 95 dogs, 650 tons of supplies, and 42 men headed for the most dangerous adventure of their lives. "The New York Times" already had written an obituary for each man.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: Antarctica is a very inhospitable place. I think it's something like Mars, it's as close to another planet as we can get on earth. It's the driest place on earth, the coldest, the windiest. There are no plants there. It's desolate, desolate with a capital D, and dangerous. Antarctica has, has killed men. They've fallen off mountains, fallen into the sea and drowned, froze to death, gone mad. It's a terrible place to live.

NARRATOR: Traveling through the Panama Canal, across the Pacific, and down past New Zealand, the expedition took 2 months to reach Antarctica. When the men began unloading supplies, a great chunk of ice crashed into one of the ships. A crewman, Benny Roth, fell into the water.

NORMAN VAUGHAN, expedition member: Benny Roth was yelling for help, "I can't swim" and as Byrd started to climb over the taftrail and to jump into the water, I among others grabbed him and pulled him back, and the second we released our grip on his clothing, like a cat he was over the rail.

NARRATOR: A lifeboat rescued Benny Roth before Byrd could get to him. But this was not the only time he had jumped into dangerous waters to save one of his men.

LISLE ROSE, HIstorian: Dick Byrd had, I think, a natural visceral instinctive sense of responsibility toward others. And I think this, this showed itself in the way he would fling himself off decks to save sailors that were drowning. An officer took care of his men.

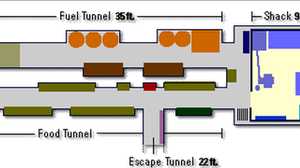

NARRATOR: Byrd had to work quickly to prepare for the brutal Antarctic winter - 4 months of total darkness from May through August. Byrd chose a site for the base camp nine miles inland. It took 3 months just to unload. Expedition members, dressed in kangaroo hide boots, caribou gloves and fur parkas, set up the camp. Byrd called it Little America.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: Having to build a base for 42 men that would last them for a year and a half. He was really building a, a tiny little city. Bringing his stuff to the base, erecting it under awful conditions of sub-zero temperatures and fierce winds and snow-storms and ice that was as hard as concrete to dig into, it was a great undertaking.

NARRATOR: Even before Little America was finished, the ships had to leave Antarctica before the ice pack froze them in.

NORMAN VAUGHAN, expedition member: That was a tremendous moment. We realized then that that was our last connection or possible connection with the outside world, our home, our family, our life until next year.

NARRATOR: Alone on the ice, Byrd and his men pushed to get work done before winter set in. The South Pole flight was still nine months away and though it was his primary goal, Byrd had also pledged to conduct scientific research.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: Antarctica was virgin territory for scientists. Glaciologists had to study how much ice was there and how it moved. The weathermen had to study the air patterns, the geologists had to study the rocks down there. So gathering scientific knowledge about Antarctica was very important at the time.

NARRATOR: But Byrd's personal passion lay in discovering uncharted territory and in being the one to claim it for the United States. From the air, he was able to map huge areas and make headlines back home. A "New York Times" reporter was on the expedition.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: Russell Owen had to send his reports to the "Times" through the radio operators, who would send it by Morse Code back to New York. Byrd had left standing orders with the operators to give him these reports so he could look them over before they were sent, and he often penciled in things that he wanted and penciled out things he didn't want.

NARRATOR: One story that was rewritten was the discovery of a vast territory by three other men from Byrd's expedition. The news was reported in "The Times" but with Byrd as the hero.

RAIMOND GOERLER, Byrd Archives: There is, I think very good evidence of a need to control everything on the expedition including any big news stories. He was the ah leader of the expedition, the ah he was ah personally responsible for all its ah finances and he simply did not want to share credit for the discoveries of the expedition with anybody.

NARRATOR: The winter night brought an end to exploration. The planes were stored in igloo hangers, and the dogs boarded in icy kennels. The perpetual darkness and temperatures as low as 72 degrees below zero drove the men into an underground existence.

NORMAN VAUGHAN, expedition member: Well you felt quite trapped. You're in one building with tunnels connecting to another building. The living space was as cramped as it could be. In the house where I was it was a very small quarters and two tiered bunks on four walls and just a stove and that' s all there was in that room.

NARRATOR: As a precaution against fumes and asphyxiation, they turned off their stoves at night. The men lived mostly on frozen provisions, supplemented by whale and seal meat. They spent the winter preparing for the spring expeditions and dealt with the monotony by playing games, watching movies and performing skits for each other. Whatever face Byrd put on for the men, he felt very alone and depended on his wife for moral support. "Darling," Marie wrote.

MARIE BYRD Quote: I'm wondering if the time will ever come when we can be like human beings and have a real home. Glory and fame may be all right but we have certainly paid well for them.

BOLLING BYRD CLARKE, daughter of Admiral Byrd: My mother was a very exceptional woman. It must have been extremely difficult for her to carry on alone with the responsibilities of the family and home.

Dear Daddy,

I love you very much. I wish you would be home more. I think I would get along much better in school if you were here.

Dicky

NARRATOR: The separation from home was hard on all the men. Enveloped in darkness, Little America became a pressure cooker.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: So people get on each other's nerves. They ah, blew up at each other. They tended to get what they call, the big eye, in Antarctica, even today, where they just stare because they were depressed and had little stimulation. Byrd had been warned about this by other polar explorers who told him, watch out for the winter. It's a very dangerous time in Antarctica.

NARRATOR: Though the Paramount cameramen made the winter look like good clean fun, there were fist fights, and an episode when one man stalked another with a gun. Alcohol was another problem. Byrd, among others, was a heavy drinker, and parties frequently became all night binges.

LISLE ROSE, Historian: He wasn't leading officers and enlisted men in a naval expedition. He was leading very individualistic scientists, adventurers, students, people who really had been pretty well used to living their own life and after all volunteered for the Byrd expedition because they wanted adventure.

NARRATOR: Finally, in August, the sun returned to Antarctica. The men began to prepare for the flight to the South Pole. But Byrd had not yet revealed who would be the pilot. The secrecy caused tension and upset Bernt Balchen.

BESS BALCHEN URBAHN, former wife of Bernt Balchen: It bothered Bernt that Byrd had a closed personality. He would take people to the side and talk to one on one. Instead of talking to everybody if he had a problem or if he wanted something specific done he should have addressed the whole group of them.

NARRATOR: Though there was tension between the two men, they needed each other. Byrd depended on Balchen's superior skill as a pilot, and Balchen wanted to share in the glory of another polar first. Finally, Byrd told Balchen, "You will fly to the South Pole with me."

It was Thanksgiving day, 1929 when Byrd's plane, the "Floyd Bennett", left for the Pole. The take off was smooth but there was soon trouble. The plane was too heavy to get over the high mountain range on the edge of the polar plateau. Balchen and Byrd were forced to dump their emergency food supplies, but still the plane could not get high enough. They were heading directly for a mountain peak.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: Experienced pilot that he was, Bernt Balchen knew there was a cold mass of air pouring over the polar plateau, and there was probably an updraft somewhere if he could find it. So he flew over to a mountain wall. And lo and behold, there was an updraft there. He got just enough of an updraft to boost the plane high, enough to get over the peak. They flew over the mountain and they were home safe.

NARRATOR: The plane circled the pole. Byrd sent a radio message, "My calculations indicate that we have reached the vicinity of the South Pole." The news was immediately relayed to New York and broadcast over loudspeakers in Times Square. The expedition had been a remarkable achievement. After fourteen months on the ice, Byrd and his men headed home.

In June, 1930, the expedition arrived in New York. Now promoted to Admiral, Byrd was honored with his biggest ticker tape parade.

But there was no time for a break. Byrd was secretly planning another expedition and had to cash in on the last one. He published a book, "Little America," a self-promoting account of his two years in Antarctica and supervised the editing of the Paramount film in his home.

BOLLING BYRD CLARKE, daughter of Admiral Byrd: I remember them splicing film together and I would sneak down the backstairs and peek ah between the cracks of the door.

EUGENE RODGERS, Journalist: This documentary won the Academy Award for best photography. It was a terrible documentary though, I must say that. It didn't really fit the history correct. It was made to show Byrd as a great hero, and to bring tears and sweat from the audience. It wasn't really historically true.

NARRATOR: Not everyone fell for it. A few 'New York sophisticates,' as Byrd called them, thought that the all-American image was wearing thin. But to most Americans, Byrd was still a hero - though the relentless schedule of public appearances was a trial for such a private man.

BYRD Quote: What a pity it is that I have to keep a stiff upper lip and go thru all kinds of stuff when I ought to be out in the woods, away from everybody.

NARRATOR: In 1931, Byrd announced a second expedition to Antarctica, to map more territory and to conduct scientific research. He would also have to come up with another spectacular and dangerous exploit to top his South Pole flight.

LISLE ROSE, Historian: So he keeps this momentum of movement and of action and of achievement going. He's really almost a guy on a treadmill.

NARRATOR: The times had changed. The country was mired in the Great Depression, and money was scarce. Byrd had to market himself aggressively to attract contributions and supplies for the expedition. It was easier to get.

STEVENSON COREY, expedition member: I was kind of at the crossroads and no roots down, particularly in business and it was a challenge to find out, as I was tough as these fellows that were doing these things.

NARRATOR: Byrd's second expedition got underway in 1933. From the beginning, it was a media event. Byrd made a deal with CBS to produce weekly broadcasts from Antarctica. General Foods was the sponsor and Grape Nuts, the official cereal of the expedition. The first of over sixty scripted broadcasts was made from the ship on the way down.

ANNOUNCER (archival): Stand by all America for now we are attempting the most spectacular feat in the annals of radio - a two-way broadcast from and to the Byrd expedition. Now in the Pacific on the way to Antarctica...

BYRD (archival): Good evening, my friends of the Columbia and General Foods. We confidently believe that in that lost world, aviation will find something of real value to humanity. What we seek lies deep in Antarctica the last refuge of mystery and the unknown.

NARRATOR: Treacherous conditions plagued the men from the start. Every day huge chunks of the ice shelf broke off. The route to Little America was so hazardous, it became known as Misery Trail. The dangers facing the expedition were featured in press reports sent home.

MURPHY Press Report: Yesterday a tractor narrowly missed plunging into a crevasse. The trail suddenly crumpled underneath the rear treads, exposing a crevasse sixty feet deep.

NARRATOR: The man in charge of all the press and radio on the expedition was Charles Murphy, a CBS correspondent who had written Byrd's biography and was his most trusted advisor.

RAIMOND GOERLER, Byrd Archives: Charles Murphy, is very media astute. This is a man who ah even before Byrd's ah expedition ah was involved in cultivating Byrd's ah image as a hero. And he was very much concerned that that image be maintained.

NARRATOR: For two years, Byrd had been planning a dramatic event. No one had ever spent a winter in the interior of Antarctica. Byrd would build a remote weather station far south of Little America where two or three men could live and conduct meteorological research during the long winter night. But secretly Byrd had been thinking about going alone. Now, difficult conditions caused delays and sealed his fate. Byrd would go out to the weather station, Advance Base, by himself - with cold, darkness and solitude his only companions. Byrd confided to Murphy that he had no other choice.

MURPHY Journal: Feb. 18, 1934 Impossible to move out enough equipment for three men. To take another, he said , would incur the almost inescapable suspicion of homosexuality.

NARRATOR: To do it alone he felt wise and proper When Byrd announced his decision to the camp, many were opposed.

STEVENSON COREY, expedition member: I said to him "bluntly Admiral, there are 56 men here on the ice, 55 of us are better equipped to go out to that base than you are, you're needed here." And, he laughed and he said, "Oh, I wouldn't ask anyone to do something that I wouldn't do myself."

MURPHY Journal: Feb. 18, 1934 It has interested me how well a man could stand solitude. Also, I have had a lot of expeditions and have had to put up with things and with men especially that have robbed them of satisfaction. This will be without those disadvantages.

LISLE ROSE, Historian: In going to Advance Base, I think Dick Byrd had run out of ideas in what to do in terms of aviation. So he really needed something I think spectacular as a means of effectively putting him before the public as this intrepid polar explorer and unique individual.

NARRATOR: Before he left, Byrd instructed his men not to attempt a rescue before the return of full daylight in six months. In a last minute note to Murphy, he admitted, "I am no radio operator, so the radio will possibly fail. This should not be any cause for worry." Once the crew completed building the 9 x 13 foot hut, Byrd was flown to the base, 123 miles south of Little America, and left alone.

BYRD Quote: March 28 They have gone at last. For over two hundred days, I'll see no human being or any living thing. The winter night is near. The temperature is bitter, from 40 to 60 below.

NARRATOR: For the first two months, Byrd kept busy with his routine of weather observations and spent time listening to music, reading, and trying to cook.

BYRD Quote: I have located very little of the food and don't know how to cook anyhow. I found some canned greens and a Virginia ham mother sent me and lived high off of those yesterday. The greens were frozen so hard I had to use a chisel to cut it into chunks for warming.

NARRATOR: Back at Little America, the men tried to keep busy throughout the winter night. Their weekly radio programs provided comic relief. It was Murphy's job to write the scripts and to cajole the men into performing.

MURPHY: "Little America, Byrd expedition calling from Little America. Temperature tonight - 59 below. Tonight we introduce for the first and probably last time, a composition. It is called "Penguins'."

JOSEPH HILL, expedition member: And our illustrious singing group was the Knights of the Gray Underwear. Dr. Gill Morgan, our seismologist was our organist. And I sang tenor. It was more as an amusement, but I do believe based on reports from home that I think people really did look forward to that program every week.

BOLLING BYRD CLARKE, daughter of Admiral Byrd: The Saturday nights when they had the broadcasts from Little America, Mother would wake us up, take us down to ah Dad's big bed. It's a great big Italian bed and ah I can remember the static and listening to the broadcast down there, they were very exciting.

NARRATOR: On June 21st, Byrd radioed Murphy a surprising message. He said he wanted to come home three months ahead of schedule. Byrd then cut the contact short saying that fumes from his stove made him feel a little 'rocky.' He signed off, as usual, with 'Cheerio.' What Byrd didn't reveal was that he had been desperately ill. Three weeks earlier, he had collapsed from carbon monoxide poisoning.

LISLE ROSE, Historian: He basically was poisoned for a prolonged period of time by fumes, which he thought were coming from his stove, but in fact were coming from his generator. He went through a pretty terrible ordeal.

NARRATOR: Byrd became dizzy and confused. He couldn't keep food down and wracking pain made it almost impossible to sleep. He lay in the freezing cold, struggling between hope and despair.

BYRD Quote: Hardest battle I have is to keep from taking an overdose of sleeping pills. Horrible to think of leaving Marie alone with the four children. Decision not to call for help based upon how they would want me to act. Fully expect to die.

NARRATOR: Byrd's radio contacts with Little America became erratic and his Morse code almost indecipherable.

JOSEPH HILL, expedition member: We began the suspicion that something was wrong with him when he would miss a, a contact, or have trouble staying on the air very long. And as time went on this became so frequent that we decided that something was really wrong, and something had to be done.

STEVENSON COREY, expedition member: We held several meetings in the mess hall, and there were factions. Some were saying "well he asked for it, now let him stew in his own juice for a while." Others fought and said, "no the old man's out there, he needs help, let's go out and rescue him."

NARRATOR: On July 20th, a tractor party left Little America for Advance Base. Murphy's press release reports a perilous trip for scientific research. No mention was made of Byrd's illness or of a rescue.

JOSEPH HILL, expedition member: We were very concerned about the men that were running the tractors to go out after him. Recognizing the difficulties, we knew that they were risking their lives literally to do it.

NARRATOR: 50 miles out, the tractors ran into huge field of crevasses. The tractor party wired Murphy.

MURPHY Report: Unable to locate trail around crevassed area. Many flags completely covered under snow. Inadvisable to proceed.

NARRATOR: Murphy instructed them to come back. He wanted to wait a month when daylight would return before risking another attempt. But for the next three days, Little America was unable to contact Advance Base. Finally, they received from Byrd an explicit call for rescue. Murphy wrote in his diary,

MURPHY Quote: Making ready for a second dash to advance base the Admiral has called for it...God help us all if anything goes wrong.

NARRATOR: But the second attempt failed because of engine problems. Murphy then received another desperate message from Byrd.

BYRD Quote: "Charlie and Bill, what in God's name is matter - do something - use all resources - do not risk life - can't keep this up. August 5, 1934

NARRATOR: On August 8th, a tractor carrying 3 men set out once again. By now, Murphy and the others were certain Byrd was close to death.

JOSEPH HILL, expedition member: We waited for the reports back from the tractor party on how they were proceeding, what difficulties they were encountering. And just holding our breath literally from report to report.

NARRATOR: For three days, the rescue party pushed through bitter cold and darkness and finally reached Byrd. The men found him thin and weak, his cabin littered with debris. But he was still alive

LISLE ROSE, Historian: He wanted to do this as a spectacular act of courage and so on. But I don't think he ever expected to run into the disaster that he did. There's very strong indication in the documents that he was embarrassed and one could even say that he was humiliated by the fact that he didn't finish his time at advance base.

NARRATOR: The tractor party sent a confidential message to Murphy:

Message from Tractor Party: REB feels unhappy about his status with the public. He feels that he is pretty well sunk and that this may make it impossible for him to make up expedition debt. 8/14

NARRATOR: Six months after Byrd's rescue, the expedition headed home. Byrd had claimed more land and conducted important scientific research, but privately, he felt he had failed. He was 47 years old.

BOLLING BYRD CLARKE, daughter of Admiral Byrd: Here was a man whom I had last seen straight-backed, black haired man and here he was, coming down the gang plank, holding on to both sides of it stooped, with some of his hair having turned gray and all I wanted to do was to just run out to him and tell him how much I loved him and how happy I was to see him.

FDR (archival): " and I extend to all of you in behalf of the American people a hearty welcome home. And let me add just one thing from the heart. Dick, I salute you."

BOLLING BYRD CLARKE, daughter of Admiral Byrd : After all the speeches were over, the crowds broke through the ropes and I can remember that I just rushed right through and up to Dad and he turned to me and he said, "not here dear, later when we're alone" and I was crushed. It had been about three years since I had seen him last. Now Dad was raised at a time when you didn't express outwardly love or pain. He may have been crying inside as much as I was but you didn't do that in public.

NARRATOR: Three years later, Byrd published Alone, an heroic version of his isolation at Advance base. It became a bestseller. The book was meant to pave the way for Byrd's next expedition. But within a short time, polar exploration would be in the hands of the U.S.government. Eventually, Byrd was needed only as a figurehead.

LISLE ROSE, Historian: He was trapped in his own self image of the intrepid polar explorer who overcame great odds and who had to go back time and time and time again to find new trials and new tests of strength. When he said to people, they don't want me anymore, what he meant was, they didn't want him as he perceived himself, as the leader of polar expeditions.

NARRATOR: No longer running the show, Byrd spent more time with Marie and his family. Perhaps, he found some solace in what he had learned from his time at Advance Base.

BOLLING BYRD CLARKE, daughter of Admiral Byrd: Out of this experience, his sense of values changed and his faith grew. And he said, in the final analysis, only two things really mattered and that was the affection and the understanding of his family.

NARRATOR: Byrd made his last trip to the ice in 1955. Two years later, the man who introduced America and generations of scientists to Antarctica died of heart failure at the age of 68. Byrd's statue at Arlington National Cemetery immortalizes the heroic persona that he spent his life creating. But that image would be tarnished. In 1971, Bernt Balchen went public with his claim that years earlier pilot Floyd Bennett had told him that Byrd had not reached the North Pole. Whatever the truth, the claim cast a shadow over the legacy of the last great polar explorer.

In an editorial after Byrd's death, The "New York Times" wrote "such men are not easy characters. They burn with a bright flame. They go on their way alone, partly because they stand on a narrow summit."